Folios/v7/Time-landscape-2019/MS-156

Katherine sat in the carriage, next to her uncle and opposite Elizabeth and her young cousin, as they approached the edge of the city. They were all silently looking out of the windows at the dark sky and the eerily empty streets. The only sound was the echo of horseshoes on the cobblestones. Everyone who hadn’t already fled the city was safely barricaded inside their homes.

Katherine shifted in her seat anxiously. She couldn’t flee at the first sign of danger like this. It went against everything she’d been working towards. What was the point of having defences if you immediately left them at the first sign of danger?

She folded her arms, while her mind desperately worked on a way to avoid having to leave with her family, to avoid abandoning Matthew. He had stayed behind in Carlisle with the other servants when Katherine’s aunt and uncle had decided to flee the city.

Their carriage joined a queue of several others waiting to be let out of the gates of the city in secret. It seemed that there were plenty of other citizens who weren’t brave enough to stand and defend their city.

When it was their turn, her uncle handed the guard a large bribe, and the gate slid open soundlessly. Their carriage was the last to pass through into the open countryside. Katherine could hear the relieved sighs of the guards as the gate began closing behind them. The citizens had escaped and the Rebels had not been alerted to the open gates.

This was Katherine’s last chance. Once those gates were closed, the soldiers would not open them again. She couldn’t leave the city now, at the moment when everything was happening. She hadn’t even had a chance to say goodbye to Matthew. She had to go back. Resolve hardening, she flung open her door and leapt from the carriage. She squeezed between the closing gates and dashed back inside the city. The guards were too shocked to react, and she ran past them, skirts held above her ankles, shooting straight down the road.

“KATHERINE FINCHLEY!” her aunt shrieked from behind the closing gates, but it was too late. Katherine was gone, already weaving her way down Carlisle’s narrow back streets, and the gates wouldn’t open again.

Katherine ran until her lungs were bursting and a stitch had developed in her side. When she stopped, she looked at the darkened buildings around her. Now she was alone, the impact of what she’d done hit her, and she suddenly couldn’t breathe. She’d left her family, in the dead of night, and her home was on the other side of the city. The lane was deserted. She brushed her skirts flat, trying not to panic. She just had to walk home. She had walked across the city every day to the castle – except then she hadn’t been wearing a dress, and it hadn’t been the dead of night, and she had been with Matthew.

She took a deep, calming breath. She was perfectly all right. It was only a ten-minute walk from here.

When she reached the gate that separated the drive of her aunt’s house from the street, Katherine’s heart sank. It was locked. Of course it was. She rattled the chain hopelessly. She was stuck outside. What a fool she had been. She dropped down onto the ground, her back against the gates, head in her hands.

“Hey!” a voice shouted, making her jump. “What are you doing?”

A lantern was making its way down the drive, and she could make out the candlelit features of the man who was carrying it.

Matthew.

She stood up. “Matthew! It’s me!”

“Katherine?”

“Please let me in,” she begged, half-choked up with relief.

“What are you doing? Did you…? You idiot!”

“I needed to be here. I couldn’t leave.”

“You’re so … urgh!” he said, running a hand through his hair in frustration. “Why did you do that?”

“I had to,” she said quietly. “Please let me in.”

He unlocked the gate silently. Katherine bit her lip, worried he was angry with her. As soon as the gate opened, though, he tugged her inside and pulled her close to him. He tucked his head against her shoulder and let out a noise that was almost a sob.

“Anything could have happened to you in the city in the dark,” he mumbled into her neck.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered. “I just couldn’t leave after all our work.” Silently she added, I couldn’t leave you.

She shyly touched her hand to the small of his back and then leant her head against his. They didn’t pull apart for a long time.

Folios/v3/Time-landscape-1854/MS-8

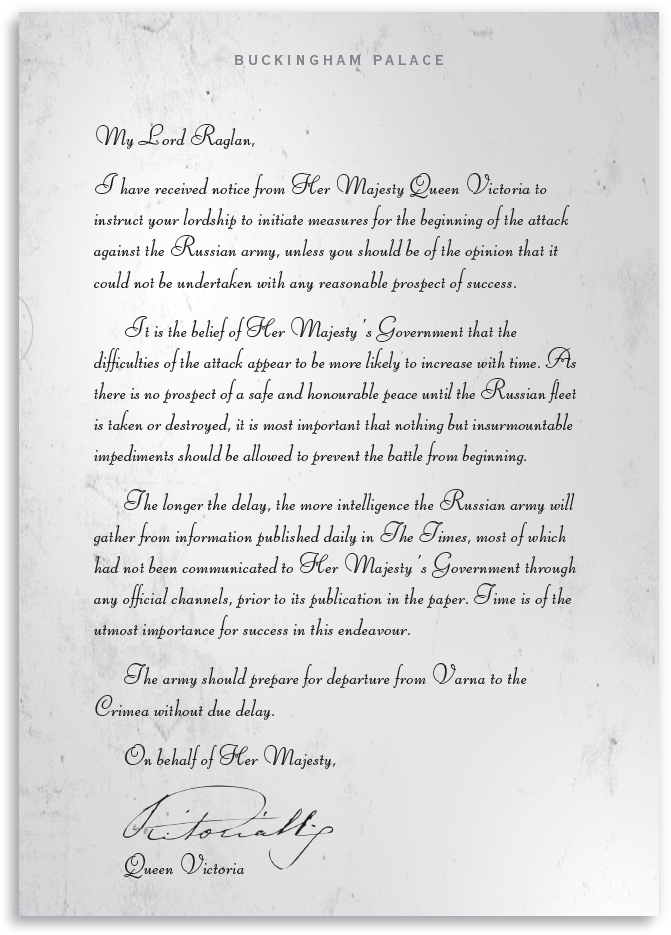

File note: |

Orders from England that began the invasion of the Crimea |

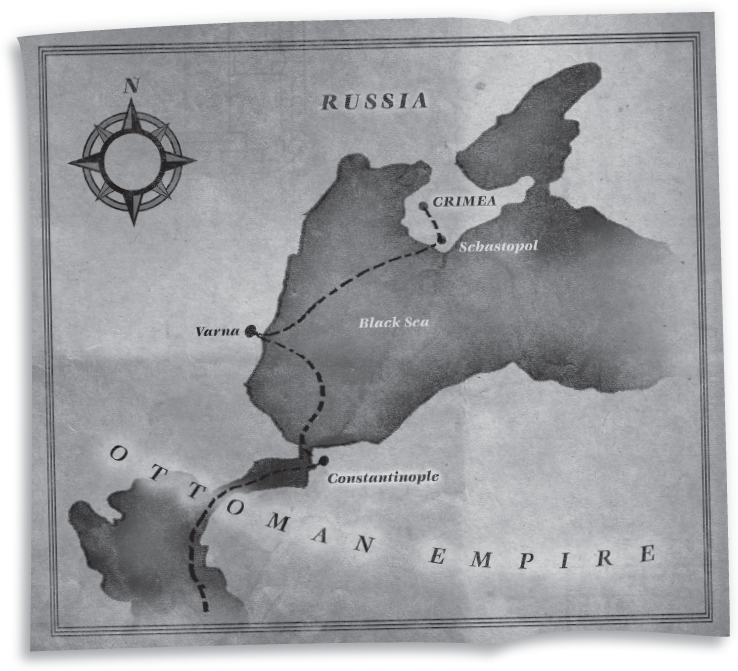

Folios/v3/Time-landscape-1854/MS-9

File note: |

Journey of the British Army through the Ottoman Empire to the Crimea. By the time the army set sail from Varna, Bulgaria, its number had been reduced, largely as a result of a cholera outbreak, to 27,000 men. The French army was severely depleted too, to around 30,000 men, and the Turks had 7,000. The Allies were in a desperate situation, with inadequate food supplies and tents that were not waterproof |

Katy leant closer against Matthew, trying to muffle her shivers in his collarbone as they waited in a queue to get a tent. She didn’t care what the other soldiers thought. She needed the warmth. She could barely feel the extremities of her body from exhaustion and bitter cold.

They had waited weeks in Varna for orders to arrive from England. Finally they had come and the regiment had left Varna for the Crimea, where the battle against the Russian army would take place. The ship had been full of drunken soldiers, cheering and hollering along to the national anthem. There had been a lot fewer of them than had set out from Southampton all those months ago. Cholera had killed hundreds of men. Aboard the ship, Katy and Matthew had stuck together, talking quietly and avoiding the rowdy men.

The voyage had lasted a week, and much of it had been spent waiting for scouting ships to decide where the troops should land. Eventually, they had all disembarked and then marched to the temporary campsite in the wind and rain. Katy was worn out now. She felt at the end of what she could handle and the war had scarcely begun.

The next day the British troops would march to meet the approaching Russian army and then the fighting would begin. They had already had their first sighting of the enemy: a group of Russian officers on the clifftop had been counting the number of English and French troops.

“Not long now,” Matthew whispered. “We’re nearly at the front of the queue.”

She nodded, trying to keep her eyes open. They just needed to get their tent and then she could sleep. She swayed as Matthew moved away from her to speak to the soldier assigning tents. She regained her balance quickly and then made more of an effort to look like she was at least partly conscious.

“I’m Matthew Galloway, of The Times newspaper,” Matthew told the soldier. “I’ve been promised accommodation while I travel with the regiment.” Matthew handed over the letter from Lord Raglan, which the soldier stared at blankly for a moment, and then handed back.

“I don’t know anything about that,” he said. “Go and talk to the general.” He pointed vaguely in the direction of a larger tent, which was obviously the centre of operations.

“Thank you for your help,” Matthew said politely, and turned towards the tent, looking a little nervous.

Katy followed him with apprehension, knowing they were probably going to have to fight to get accommodation. In Varna it had been easy to get a tent, but as more of Matthew’s articles had been published in The Times he had begun to be treated with increasing distrust and even aggression.

“Matthew, wait,” she called, dropping her bag and pulling him close. “It’s going to be fine. You can do this.”

He held on tight to her as if she was the only thing keeping him upright. His breath was hot against her throat.

“What would I do without you?” he replied.

She shivered against him, and bent her face into his hair, smiling as she absorbed the heat of his skin. “Probably shrivel up and die, like the delicate little flower that you are.”

“Most likely,” he agreed easily. After a moment, he drew back. She took the hint and pulled away, even though she felt like she could hold him for ever. A strand of hair had fallen into his eyes, and she was unable to resist brushing it away. She didn’t care that the soldiers would think her behaviour odd.

He turned and walked over to the tent. He held up a hand as if to knock, then stared at the canvas, at a loss. Katy, who had followed him, cleared her throat noisily. A soldier poked his head out. “Yes?”

“We, er, we were told to report to the general,” Matthew said. “Is he here?”

The soldier exhaled through his teeth. “He’s very busy. Do you have an appointment?”

“No. I need to speak to him about accommodation. I’m a journalist for The Times: Matthew Galloway.”

The man grunted as he gestured for them to follow him inside.

“The general is in a meeting now,” the soldier said, pointing to a man with his back to them who was with a group of officers gathered around a table. They were probably discussing supplies, or lack of them, Katy thought.

The soldier indicated a bench along the side of the tent and they sank down on it gratefully to wait. It was the first time they’d sat down since they’d left the ship. Katy watched the backs of the soldiers with curiosity, admiring how neatly pressed their uniforms were despite the dirty surroundings.

Eventually the meeting ended and the general turned to face them. Katy stared at him in horror.

It was the officer who had caught her reading Lord Somerset’s library books.

He knew who she was.

Katy closed her eyes tightly and supressed a disbelieving groan.

> ALERT: Crisis imminent in time-landscape 1854

> Actions of subject allocation “KATY” may soon become known to subject allocation “MATTHEW”, which will be detrimental to the progress of the objective

> Intervention recommended

>> Intervention denied