Big Boy Leaves Home

— 1938 —

New York: HarperCollins/Olive Editions, 2021; published in the collection Uncle Tom’s Children; with an introduction by Richard Yarborough; 50 pages; originally published in 1938

FIRST LINES

Yo mama don wear no drawers…

Clearly, the voice rose out of the woods, and died away. Like an echo another voice caught it up:

Ah seena when she pulled em off…

Another, shrill, cracking, adolescent:

N she washed ’em in alcohol…

Then a quartet of voices, blending in harmony, floated high above the tree tops:

N she hung ’em out in the hall…

Laughing easily, four black boys came out of the woods into cleared pasture. They walked lollingly in bare feet, beating tangled vines and bushes with long sticks.

PLOT SUMMARY

In the Jim Crow South, four young Black friends have cut school and walk boldly through a white farmer’s woods, aware of the danger if they are caught. Taunting one another, full of boyish bravado, they eventually strip down in the heat of the day and jump into a swimming hole.

Suddenly, a young white woman appears. As the naked boys scramble to retrieve their clothes, she screams. They hear the crack of a shot. One body falls. A man in a soldier’s uniform appears with a rifle and the scene quickly escalates as Big Boy, strongest and largest of the four, grabs for the weapon. The instant of murderous violence that follows will force Big Boy’s parents to make a fateful decision, certain that a lynch mob will soon be hunting their child.

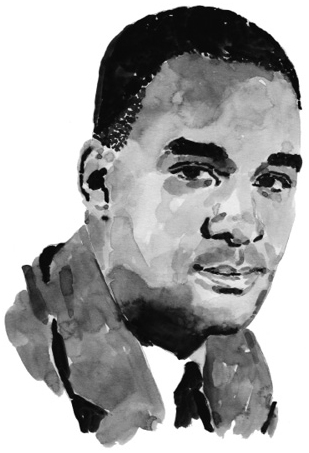

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: RICHARD WRIGHT

One of the most influential American writers of the last century, Richard Wright was born on September 4, 1908, on a Mississippi plantation, to a sharecropper father and a schoolteacher mother. His grandfathers, both born enslaved, had won emancipation fighting for the Union in the Civil War. When Wright was six, his father deserted the family and Wright’s mother moved to Natchez, Mississippi, where she took menial jobs. After she was felled by a stroke when Wright was ten, he went to live with his grandmother, a strict Seventh-day Adventist, in Jackson, Mississippi.

A gifted student, at age fifteen Wright had published a story—now lost—“The Voodoo of Hell’s Half-Acre,” in Jackson’s Southern Register, a Black newspaper. He was forced to drop out of high school to find work and he took jobs as a porter and bellhop, always facing the threat of racist violence. To use the local library, he had to forge letters pretending that he was checking out books for a white man. But he discovered the work of journalist and cultural critic H. L. Mencken and was profoundly influenced by Mencken’s style and withering assault on an anti-intellectual American society including the “low-down politicians, prehensile town boomers, ignorant hedge preachers, and other such vermin” that accepted and celebrated lynching. “He was using words as a weapon,” Wright later wrote, “using them as one would use a club…. Then, maybe, perhaps I could use them as a weapon?”

At nineteen, Wright moved to Chicago in 1927, where he lived for the next decade, working at a succession of humble jobs: porter, busboy, and post office clerk. During the Great Depression, Chicago was a center of left-wing politics and Wright met a group of radical workers. He joined the John Reed Club, a group of communist writers and artists, and by 1933 had joined the Communist Party. Soon after, his poems and writing began to appear in leftist publications such as Left Front and New Masses, where he published his first article about boxer Joe Louis. He also worked as a college campus communist organizer and as a reporter for the Daily Worker.

In 1935, Wright joined the Federal Writers’ Project, a New Deal program to provide work to writers during the Depression by creating city and state guidebooks that collected folklore and oral history. Its projects included the landmark oral history project “Born in Slavery,” which included more than twenty-three hundred firsthand accounts of formerly enslaved people. Wright contributed to the guidebooks the project was creating and acted as a supervisor as well. The government work also permitted him to continue his own creative work. Leaving Chicago for Harlem in 1937, he again worked with the Federal Writers’ Project and came into contact with other Black writers including Ralph Ellison and a young James Baldwin (see entry).

During this time, Wright unsuccessfully sought to sell a first novel (published posthumously in 1963 as Lawd Today). But Big Boy Leaves Home appeared in an anthology of Black fiction in 1936 and another prizewinning piece, “Fire and Cloud,” appeared in Story magazine two years later. These and other novellas were collected in Uncle Tom’s Children (1938), winning Wright immediate critical renown. In 1940, Uncle Tom’s Children was reissued with “The Ethics of Living Jim Crow,” a stark autobiographical essay underscoring the indignities and violence that Black Americans confronted daily.

Awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, Wright was able to complete Native Son, his first published novel. Released in 1940, it was a landmark work of fiction about Bigger Thomas, a young man growing up in Chicago’s Depression-era poverty. A critical sensation, it was chosen as Main Selection by the powerful Book-of-the-Month Club—which demanded the deletion of scenes of masturbation and interracial sex—a major commercial breakthrough for Wright. (Zora Neale Hurston’s first novel, Jonah’s Gourd Vine, had earlier been an alternate selection of the book club.) Native Son became the first best seller by a Black writer and was later adapted for Broadway, directed by Orson Welles.

After a brief marriage to ballet dancer and dance teacher Dhimah Rose Meidman in 1939, Wright wed Ellen Poplowitz, a Communist Party member, in 1941. After the birth of their first daughter, Julia, they moved into the Brooklyn home of influential editor George Davis. The large house had become an international literary and artistic commune, with residents including W. H. Auden and Carson McCullers (see entry), whose first novel, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, Wright had reviewed admiringly before their meeting. By then, a disillusioned Wright had left the Communist Party, rejecting its orthodoxy and the Stalinist purges; a 1944 essay, “I Tried to Be a Communist,” which appeared in the Atlantic Monthly, was later published in a 1949 collection called The God That Failed.

Wright’s next book was the memoir Black Boy, published in 1945. Selected again by the Book-of-the-Month Club, it remained on the best-seller list for the larger part of that year. But despite Wright’s growing fame and success, he was dismayed by the persistent discrimination he and his white wife faced. With the assistance of Gertrude Stein, the thirty-eight-year-old Wright moved his family to Paris in 1946, where a second daughter, Rachel, was born. Richard Wright never returned to America.

Wright found both literary celebrity and acceptance in the French intellectual circle of Camus, Sartre, and Simone de Beauvoir. But over time, he lost much of his American audience. His fellow expatriate James Baldwin later criticized Wright in “Everybody’s Protest Novel” and “Many Thousands Gone,” essays collected in Baldwin’s 1955 Notes of a Native Son, which attacked Native Son as confirming racist stereotypes of Black people. It ended their friendship.

Three of Wright’s novels written in France—The Outsider (1953), Savage Holiday (1954), and The Long Dream (1958)—explored existential themes and were more successful overseas than in the United States. His other books of reportage, political commentary, and autobiography were largely overlooked in the United States. Richard Wright died of a heart attack in Paris on November 28, 1960, at the age of fifty-two.

A second novel unpublished during Wright’s life, The Man Who Lived Underground, was issued by the Library of America in 2021.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ IT

More than eighty years later, Wright’s intense, compact story about a young boy whose life is overturned in a moment of stunning bloodshed remains an electric piece of writing. Wright explores the daily dehumanizing impact of Jim Crow America and the constant threat of violence from white people that Black people endured. Echoes of the story can be found in Colson Whitehead’s 2019 novel, The Nickel Boys, also included in this collection (see entry). The issues of racism and violence against young Black men are still profoundly timely.

Written largely in dialogue, Big Boy Leaves Home remains a vividly arresting work out of the realist-naturalist school. In his introduction to the collection, UCLA professor Richard Yarborough wrote that Wright “was propelled by a fierce determination to break the silence surrounding racism in the United States, a silence maintained in the interest of white supremacy and one to which too many blacks had acceded.”

Nevertheless, in an essay written two years after Uncle Tom’s Children appeared, Wright voiced regret over the collection’s publication, contending that he had made it too easy for white readers to assuage their guilt. “When the reviews of that book began to appear, I realized that I had made an awfully naïve mistake,” he wrote in “How ‘Bigger’ Was Born” in 1940. “I found that I had written a book which even bankers’ daughters could read and weep over and feel good about. I swore to myself that if I ever wrote another book, no one would weep over it; that it would be so hard and deep that they would have to face it without the consolation of tears. It was this that made me get to work in dead earnest.”

Native Son would fulfill Wright’s need to write a book that was “hard and deep.” But there is no question that Big Boy Leaves Home is hardly a story to be read and then “feel good about.” Its power lies in the vision of what life meant to be a young Black boy who is thrust suddenly into a world in which he is on his own—an unforgiving world in which survival is finally all that matters.

WHAT TO READ NEXT

The simplest answer is to move on to the other four works collected in Uncle Tom’s Children, including Down by the Riverside, a highly charged narrative of a man desperately struggling to transport his pregnant wife to a hospital during a flood.

Beyond these novellas, Wright’s novel Native Son and memoir Black Boy remain vital parts of the canon of modern American literature.

“Richard Wright was the first African American writer to enter mainstream American literature. A watershed figure in African American literature, he pushed back the horizons for black writers,” wrote biographer Hazel Rowley. “At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Wright’s writing continued to evoke passionate responses, from deep admiration to vehement hostility. He is an uncomfortable writer. He challenges, he tells painful truths, he is a disturber of the peace. He was never interested in pleasing readers. Wright wanted his words to be weapons.”