One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

— 1962 —

New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005; translated from the Russian by H. T. Willets with an introduction by Katherine Shonk; 182 pages; originally published in the Russian magazine Novy Mir, November 1962

FIRST LINES

The hammer banged reveille on the rail outside camp HQ at five o’clock as always. Time to get up. The ragged noise was muffled by ice two fingers thick on the windows and soon died away. Too cold for the warder to go on hammering.

The jangling stopped. Outside, it was still as dark as when Shukhov had gotten up in the night to use the latrine bucket—pitch-black, except for three yellow lights visible from the window, two in the perimeter, one inside the camp.

PLOT SUMMARY

Set in one of Stalin’s notorious Soviet forced-labor camps, the first novel by Nobel Prize laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn recounts a single day in the brutal existence of a man accused of spying for the Germans during World War II.

Based on Solzhenitsyn’s own experiences as a political prisoner, or zek, the story follows inmate “Shcha-854”—Ivan Denisovich Shukhov—from the moment he wakes.

Feeling sick, Shukhov lies in his bunk, trying to stay warm, his feet tucked into a sleeve of his coat. As he listens, men carry out heavy latrine buckets. “He heard the orderlies trudging heavily down the corridor with the tub that held eight pails of slops. Light work for the unfit, they call it, but just try getting the thing out without spilling it!”

Another inmate says the temperature is twenty below. The prisoners check the thermometer daily because they don’t have to work if the temperature reaches forty-one degrees below.

As Shukhov and his fellow squad members work, they seek any chance to wheedle extra food or a moment’s warmth. In direct, straightforward prose, Solzhenitsyn strips bare the struggle to simply live for the next day:

Shukhov felt pleased with life as he went to sleep. A lot of good things had happened that day. He hadn’t been thrown in the hole…. He’d swiped the extra gruel at dinnertime.

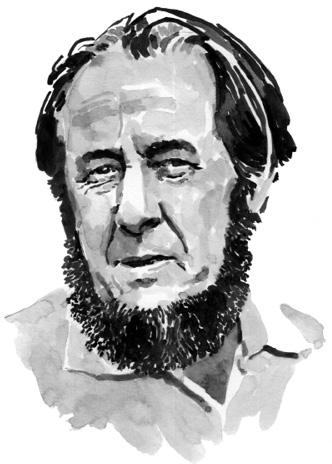

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: ALEKSANDR SOLZHENITSYN

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was born on December 11, 1918, to a widowed mother. His father, a Cossack army officer, had died in a hunting accident before his birth. The Russian Revolution upended the family’s life when their farm was taken by the state. Well-educated and a devout Russian Orthodox, his mother raised him in that faith even after the communist takeover.

Solzhenitsyn attended university, and though he graduated with a mathematics degree, he was always interested in literature. When World War II broke out, he joined the army and rose to the rank of captain. In 1945, he was arrested for writing a letter deemed critical of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. Solzhenitsyn spent eight years in labor camps for this offense—the same crime for which Shukhov is sentenced. Once released and “rehabilitated” in 1956, he taught mathematics and began to write.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, there was a relaxing of the former dictator’s most brutal practices and liberalization in the arts under Nikita Khrushchev. Permission was granted to a literary journal called Novy Mir (New World) to publish One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich in 1962, which would have been unthinkable under Stalin. It was a sensation that brought Solzhenitsyn overnight comparisons with Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, the giants of Russian literature.

But the Cold War–era thaw was brief. The period of liberalization ended and Solzhenitsyn was soon forbidden to publish in the Soviet Union. Some of his work appeared in the clandestine Russian dissident literature known as samizdat. His books were also spirited out of the country and appeared in other markets. Two novels, First Circle (republished as In the First Circle) and Cancer Ward, both appeared in English in 1968 to great acclaim.

In 1970 came word that Solzhenitsyn—on the strength of these works—had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. He chose not to leave the Soviet Union to accept the award, in fear that he would not be allowed to return home. Bestowing the prize in his absence, the award presenter of the Swedish Academy said:

Such are the words of Alexander Solzhenitsyn. They speak to us of matters that we need to hear more than ever before, of the individual’s indestructible dignity. Wherever that dignity is violated, whatever the reason or the means, his message is not only an accusation but also an assurance: those who commit such a violation are the only ones to be degraded by it.

Next Solzhenitsyn published a historical epic called August 1914 (1971), telling of Russia’s devastating defeat by Germany in World War I. Even more significantly, in 1973 the first parts of a grand opus exposing Soviet labor camps were sent to publishers in Paris and the United States on microfilm. In three volumes, it revealed the history of the enormous network of prison camps in a monumental literary and historical record that was eventually published as The Gulag Archipelago. Soon after, Solzhenitsyn was arrested, charged with treason, and exiled from the Soviet Union in February 1974.

He eventually settled somewhat reclusively in a secluded estate in Cavendish, Vermont. While critical of Soviet communism, Solzhenitsyn did not embrace American democracy. In writings and rare speeches, he was critical of American foreign policy and decried Western consumerism. In one public appearance, he addressed Harvard’s 1978 commencement and criticized a country he called spiritually weak and a government that capitulated in Vietnam.

“Many in the West did not know what to make of the man,” Michael T. Kaufman wrote in the New York Times. “He was perceived as a great writer and hero who had defied the Russian authorities. Yet he seemed willing to lash out at everyone else as well—democrats, secularists, capitalists, liberals and consumers.”

In 1994, after the Soviet Union collapsed, Solzhenitsyn returned to an utterly changed Russia. Through initially approving of Vladimir Putin, he later criticized the Russian leader as antidemocratic and in 1994 said the country was an oligarchy. Yet, wrote Michael T. Kaufman, “In the final years of his life, Solzhenitsyn had spoken approvingly of a ‘restoration’ of Russia under Vladimir Putin, and was criticized in some quarters as increasingly nationalist.”

Having far outlived the Soviet Union, he died in Moscow in August 2008 at the age of eighty-nine.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ IT

It is brilliant writing. It is a riveting story of dehumanizing cruelty and human resilience. It is a historical document of enormous importance. These reasons place One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich among the twentieth century’s most significant works of fiction. But the appearance of writing critical of the murderous dictator of the Soviet Union nine years after Stalin’s death was even more extraordinary. It made history because Solzhenitsyn laid bare the brutality of the vast network of prison camps, the destructive legacy of collectivization of farms, and the imprisonment of people based on religion or other factors perceived as “disloyal.”

On the centennial of the novelist’s birth, biographer Michael Scammel wrote:

Solzhenitsyn should be remembered for his role as a truth-teller. He risked his all to drive a stake through the heart of Soviet communism and did more than any other single human being to undermine its credibility and bring the Soviet state to its knees.

This slim volume is one of the most consequential reminders of the great cost of tyranny and the destruction it breeds.

WHAT TO READ NEXT

Alluding to one of Dante’s circles of Hell, In the First Circle (2009) is a revised version of Solzhenitsyn’s highly autobiographical novel first published in 1968 as The First Circle. It depicts zeks who are prisoners, but instead of doing forced labor they do research and development for the Soviet Union.

In writing about Solzhenitsyn in 1968 in the New York Times, Soviet literature expert Patricia Blake summed up the extraordinary impact of both One Day and The First Circle:

They compel the human imagination to participate in the agony and murder of millions that have been the distinguishing feature of our age. Such a task could only have been accomplished by literature, performing here what may be, after the historical cataclysm of Stalinism and Nazism, its highest cathartic function.