Surfacing

— 1972 —

New York: Anchor Books, 1998; 199 pages

FIRST LINES

I can’t believe I’m on this road again, twisting along past the lake where the white birches are dying, the disease is spreading up from the south, and I notice they now have seaplanes for hire. But this is still near the city limits; we didn’t go through, it’s swelled enough to have a bypass, that’s success.

PLOT SUMMARY

The unnamed woman artist who narrates this compelling, discomforting story is on a quest. With her boyfriend Joe and a married couple, David and Anna, she is traveling back to her family’s island cabin on a remote Canadian lake in search of her missing father. Seeking clues to his disappearance in the abandoned cabin and the surrounding woods, she is moving back through time and memory as well.

Although not precisely specified, the setting is the late 1960s or the cusp of the 1970s, and the encroachment of Vietnam War–era American culture—“the disease is spreading up from the south”—is ever present. The threat is also environmental, as the artist/narrator sees the lake’s natural state despoiled by trash, motorboats, and tourists arriving by seaplane.

What starts out as the mystery of her vanished father becomes a much more complex psychological detective story and spiritual journey. As the artist observes David and Anna’s uncomfortable banter heading toward a marital meltdown, she ponders her own future with Joe. Questions of men and sex and power plague her, coming together with the assault on nature she is watching.

Eventually, these personal and political conflicts crash and shake her to the core. Thinking about the men she has “leafed through,” she says, “But then I realized it wasn’t the men I hated, it was the Americans, the human beings, men and women both. They’d had their chance but they had turned against the gods, and it was time for me to choose sides.”

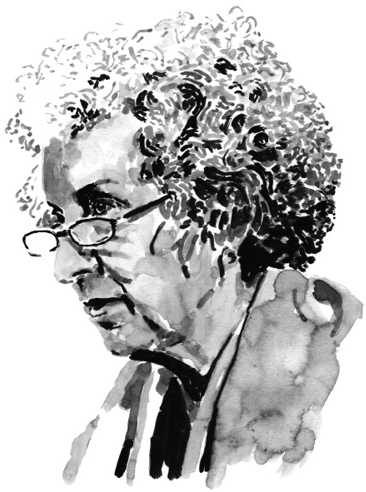

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: MARGARET ATWOOD

There is much more to poet, novelist, and essayist Margaret Atwood than “Blessed be the fruit,” one of the signature catchphrases from her 1985 dystopian novel, The Handmaid’s Tale. The American political atmosphere after the 2016 presidential election, and the debut of a television miniseries based on that novel, have elevated both book and author to cultural icon status. Politically and environmentally outspoken, Atwood also has more than 2 million followers on her Twitter account.

But her fame and success were a long time in the making. Margaret Atwood has written more than fifty books of poetry, essays, and fiction, including graphic novels, published in more than forty-five countries.

Atwood was born November 18, 1939, in Ottawa, the daughter of an entomologist father and mother who was a dietitian and nutritionist. Her father’s work in forest entomology gives some context to Surfacing, as Atwood spent considerable time in the woods while her father did research. She told an interviewer, “I grew up in and out of the bush.” This kept her out of regular school until she reached eighth grade.

Like her parents, she was a voracious reader. “They didn’t encourage me to become a writer, exactly, but they gave me a more important kind of support,” she told writer Joyce Carol Oates in a New York Times interview, “that is, they expected me to make use of my intelligence and abilities and they did not pressure me into getting married.”

After high school in Toronto, she graduated in 1961 from Victoria College at the University of Toronto and then gained her master’s degree in literature at Radcliffe in 1962. She published a series of poetry collections and also began teaching at the university level. She married Jim Polk, an American writer, in 1968. And in 1969, her first novel, The Edible Woman, was published. Divorced in 1973, she began a long relationship with Canadian novelist Graeme Gibson. Their daughter was born in 1976. In the meantime, Surfacing, her second novel, appeared in 1972.

Atwood continued teaching and publishing poetry and fiction through the 1970s in work that explored identity, gender, and sexual politics. The publication of The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) brought a Booker Prize nomination, as did Cat’s Eye (1988), the story of a painter reflecting on her childhood and teen years. In 2000, her tenth novel, The Blind Assassin, was published to great acclaim and won the coveted Booker Prize.

Writing what she called “speculative fiction,” she followed with Oryx and Crake (2003), the first of a dystopian trilogy in a world struggling with overpopulation that continued with The Year of the Flood (2009) and MaddAddam (2013). In 2019 The Testaments, a sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale, was published, becoming an international best seller and sharing the Booker Prize.

Her longtime partner, Graeme Gibson, died, suffering dementia, in 2019; he was eighty-five. At this writing, Margaret Atwood resides in Toronto.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ IT

Surfacing was clearly addressing Canadian identity and the French-Canadian separatist movement, which was at its peak when the novel was published. Half a century later, these political concerns are no longer at the forefront. But the novel is not stuck in a time warp.

Atwood’s artist/narrator is a woman who is searching for more than just her missing father. “Atwood’s best novels bring to bear a psychologist’s grasp of deep, interior forces and a mad scientist’s knack for conceptual experiments that can draw these forces out into the open,” wrote Jia Tolentino appraising Atwood in the New Yorker. And that is very much the case here.

Surfacing is vivid and deeply felt. For example, in a vibrant passage, she describes the general store in the lakeside village she had visited as a child:

Madame sold khaki-colored penny candies which we were forbidden to eat, but her main source of power was that she had only one hand. Her other arm ended in a soft pink snout like an elephant’s trunk and she broke the parcel string by wrapping it around her stump and pulling. This arm devoid of a hand was for me a great mystery, almost as puzzling as Jesus.

Atwood’s descriptive powers are often dazzling, which makes the book a pleasure to read. Then, the mood shifts—somewhat abruptly—as Atwood works in a more complex style toward the novel’s climax. As the reader is taken more deeply into the consciousness of the woman artist, we are caught by those “interior forces” that make this such a deeply provocative work.

WHAT TO READ NEXT

If you have not read Atwood’s most famous work, it is time to take in The Handmaid’s Tale. In case you haven’t heard, it takes place in a near-future American theocracy in which some women are captive breeding concubines, ritually raped each month by a “Commander” who controls them and every aspect of their lives.

Published in 1985, during the ascendence of the “Moral Majority” and the Reagan years, it acquired new timeliness in our recent era of political turmoil, the rise of evangelism, and growing American authoritarianism. It is without question a chilling view of a dictatorial, patriarchal state, governed by religious fanaticism. While I found the writing stilted at times and the final section presented as an academic’s research somewhat contrived, it is certainly a contemporary cultural marker.

Written in part to answer questions Atwood had received from readers over the years, The Testaments, its sequel, has been both a critical and commercial success. If dystopian Atwood is what you want, look to Oryx and Crake—on the BBC list of “100 Novels That Shaped Our World”—the first of the MaddAddam trilogy, followed by The Year of the Flood (2009) and MaddAddam (2013). Of Atwood’s earlier works, Cat’s Eye and The Blind Assassin are considered among her best.