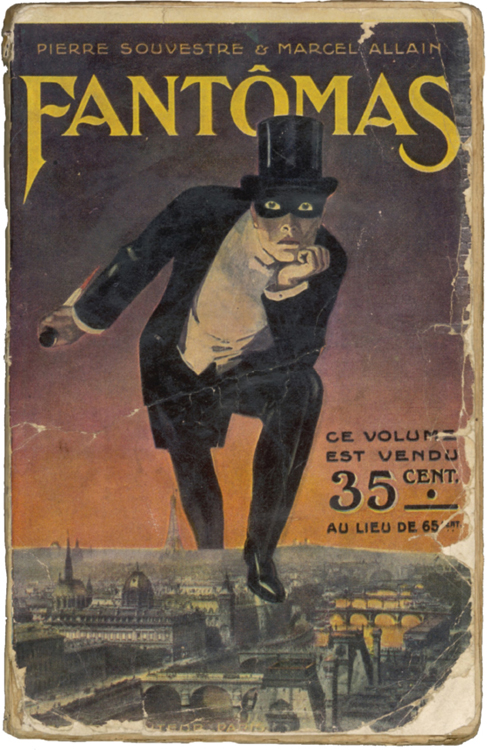

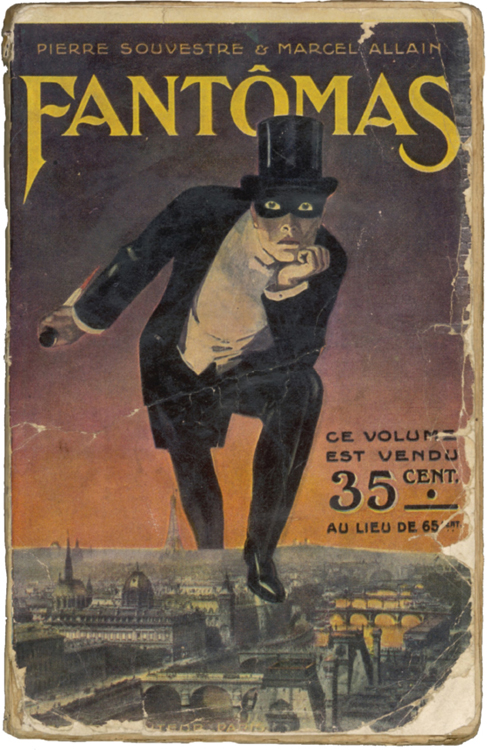

FANTÔMAS: cover of the first edition of the book, which launched the celebrated masked master-criminal

To go masked has always been a metaphor for man’s ambivalent nature. Both liberating and inhibiting, the mask can hide the face of evil, mute the glory of the divine, or aid the trickster in duplicity. In particular, the domino, covering only the area around the eyes, became the favored disguise of modern malefactors. But how many know that the comic book and movie characters who wear it—Batman, The Spirit, The Shadow, the Phantom of the Opera, even the Lone Ranger—do so because of a villain born in 1911 in Paris?

FANTÔMAS: cover of the first edition of the book, which launched the celebrated masked master-criminal

Fantômas (pronounced ‘Fanto-marz’) first saw the light—or, rather, the dark—in February 1911, as the star of pulp novels by Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain. The cover of the first issue became instantly iconic. A giant masked man in white tie, tails and a silk hat looms over night-time Paris, bloody dagger in hand. He could be stepping over the window sill into a room where someone sleeps—except that the sleeper is the city and all who live there. In his steady, amused gaze one sees all the ambivalent glamour of organized evil.

Reading the first lines of Fantômas, buyers were not disappointed.

“What is Fantômas?”

“No one—and yet, yes, it is someone.”

“And what does this ‘someone’ do?”

“Spreads terror!”

Fantômas was as good as his word. A force for mindless violence, he inflicts evil as much for pleasure as profit. Acid replaces perfume in the dispensers of a department store and poisoned bouquets are sent to cabaret stars. He sets loose giant pythons and plague-infected rats. Floors open beneath his victims, plunging them into hidden rivers. Others suffocate when a room fills with sand. Trains are derailed, liners sunk, buses sent crashing through the walls of banks, admitting masked apaches brandishing pistols. Loyal to nobody, Fantômas punishes a disobedient henchman by making him the human clapper in a giant bell. As it tolls, blood splashes to the streets, mixed with the precious stones he has stolen.

Fantômas doesn’t have it entirely his own way. He’s opposed by the dogged Inspector Juve, who never manages to corner him, and is in fact often outfoxed. In one novel, Juve is jailed, suspected of being the very villain he pursues. If the bumbling Juve reminds us of Inspector Clouseau in the Pink Panther films, Fantômas, in his effortless malevolence, resembles Professor John Moriarty, arch-villain of the Sherlock Holmes stories. Moriarty, who first appeared in 1893, may have partly inspired Souvestre and Allain, who also drew on the character of Arsene Lupin, the gentleman jewel thief and master of disguise created by Maurice Leblanc in 1905.

To readers in 1911, however, Fantômas and his thousand apache street thugs would have suggested only one thing—the Bonnot Gang. The bande a Bonnot rampaged across France in 1911 and 1912. Long before such American bandits as John Dillinger and Bonnie and Clyde, they employed automobiles in their daring daylight bank raids; the press originally called them “The Auto Gang.” Yet they had no use for money. Anarchists, they hoped by attacking the financial system to destabilize society. Decisions within the group, which included five women, were made collectively: Jules Bonnot, whom the press assigned as leader, was simply a spokesman. Teetotallers and vegetarians, unemotional and remorseless, they were ready to die for The Cause. In them, Europe experienced its first taste of modern political terrorism.

In contrast to their evil creation, the inventors of Fantômas were wimps. Young lawyers turned journalists, they were co-editing an automobile magazine when the publisher Fayard put out a call for writers who could produce a novel a month in a series that would break into the lucrative working-class market.

The ordinariness of Souvestre and Allain helps explain their success. Even if they had nothing in common with Fantômas, they knew what appealed to the average reader. Writing alternate chapters, they recited their text aloud into Dictaphones for transcription by secretaries. As there was no time to read each other’s work, they often had only a vague idea of the story.

As with Sherlock Holmes and James Bond, the movies made Fantômas. During 1913 and 1914, Gaumont produced a series of Fantômas serials. All were directed by Louis Feuillade, who was no more like their villain than were Souvestre and Allain. Middle-aged, conservative, a family man with a handle-bar moustache, he was brought up a strict Catholic and spent four years in the cavalry. While sharing the authors’ right-wing values, however, he sensed that audiences both dreaded yet secretly craved mindless violence. As critic David Thomson observes, “He foresaw that people who went into the dark to participate in stories, no matter how sophisticated their world, were still primitive creatures.”

When Souvestre, only 39, died in 1914, Allain carried on, and even invented some new characters—none, however, with the glamor of Fantômas. Instead, Feuillade created Les Vampires, a criminal gang that carried off its flamboyant crimes with a dash of theatricality and sex. Ballet dancers, stage performers and acrobats joined the cast. The 10 episodes of Les Vampires last seven and a half hours during which the forces of law and order, led by an investigative reporter, pursue the gang as its members murder, rob and kidnap.

Audiences came to know Feuillade’s signature, an incongruous mixture of futuristic fantasy, crime-fighting and drawing-room melodrama. In the first episode of Les Vampires, an employee of the newspaper who steals the journalist’s dossier on the Vampires does so because he needs money to keep a new baby, with a wet nurse, in the country. Just as the journalist forgives him, a headless body is reported found in a swamp. In a modern film, the next shot would show the reporter standing over the corpse. Instead, Feuillade has him check in with his boss and collect a chit for travel expenses. Then he drops by the house he shares with his mother, who has packed his overnight bag. As they embrace, she remembers an old family friend living near the crime scene, and insists on writing down the name and address. Later, the reporter dutifully makes a social call.

Feuillade’s most ingenious invention for Les Vampires is a female gangster who calls herself, in a not-very-challenging anagram, Irma Vep. Daringly dressed in a skintight black body stocking, Irma flits in and out of the story, running rings round police and reporters. Played by former acrobat Jean Roques, who renamed herself Musidora, Irma and her outfit created a sensation at a time when women were expected to dress in multiple and voluminous layers of heavy clothing.

By now, Paris’s intellectuals, and in particular the Surrealists, had discovered Feuillade. Rene Magritte, Robert Desnos, Guillaume Apollinaire and Blaise Cendrars all praised the films. The suburban villas of Les Vampires, with secret passages, cellars where kidnapped bankers were held, and where glowing messages appeared on walls, showed, in the words of poet Paul Éluard, that “there is another world—but it is in this one.” Revering dreams and spontaneity, the Surrealists relished the fact that Feuillade was no intellectual, and never analyzed what his biographer called “the strange, surrealist flashes of anarchy which spark through the work of this pillar of society [and] can only be explained as some sort of unconscious revolt to which he gave rein in his dreams.”

France’s wartime bureaucracy was less enthusiastic. The propaganda ministry accused Feuillade of further alarming a public already spooked by zeppelin raids and artillery bombardment. It briefly banned Les Vampires. Hurriedly, Gaumont produced a new serial, Judex. Its mysterious and all-powerful hero, wrapped in a black cloak and masked by a dark hat, wasn’t a criminal mastermind like Fantômas, but a vigilante who used his minions and skill at disguise to punish evil-doers and redress wrongs. Shrewdly, Feuillade moved his settings out of Paris and into the countryside. Children, animals and orphans took center stage. Judex is Les Vampires as seen by the newspaper employee who stole to pay his wet nurse.

When the war ended, Feuillade launched one more shocker, Tih-Minh. Set in Nice, it shows the Vampires regrouping on the Riviera, swindling wealthy gamblers and dealing in drugs. Filming in casinos, depicting high-stakes gambling and semi-naked women stoned on hashish, Tih-Minh offered a glimpse of the sinful delights that awaited France during the crazy years into which the nation was about to descend: a world in which Irma Vep, the Vampires and Fantômas might feel completely at home.

Feuillade died in Nice in 1925. He’s buried in the cimetière Saint-Gérard in Lunel, Herault, where a high school has been named in his honor. His true monument is the films of Fantômas and the Vampires, both of whom he made immortal. Aside from numerous movies, radio and TV adaptations, the Souvestre and Allain books are still in print, while a number of new novels have used their characters. Fantômas also inspired the criminal genius Doctor Mabuse in the novels of Norbert Jacques, adapted by Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou into a highly successful series of films.

Among more recent imitators, George Franju’s film Judex (1963) sensitively recreated Feuillade’s original, respecting the rural setting but retaining the allure of a Musidora look-alike in the person of Francine Berge, who fills a cat suit to even more erotic effect. Musidora was again rivaled by Maggie Cheung in Olivier Assayas’s 1996 Irma Vep, playing a star of Asian action cinema who comes to Paris from Hong Kong to act in a remake of Les Vampires.

Louis Feuillade, 1915