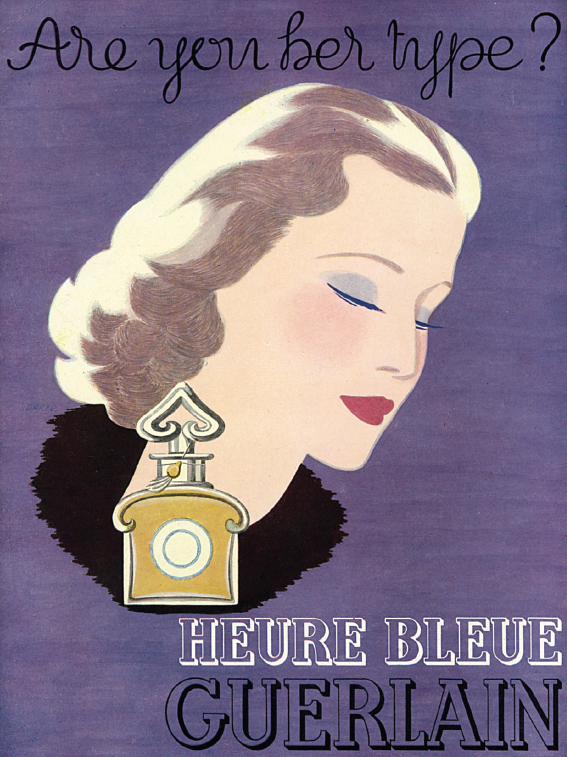

Advertisement for the classic Guerlain fragrance, L’Heure Bleue, 1930s, USA.

“There was a peculiar smell that emanated from the coffeehouse terraces of Montparnasse,” wrote author Frederick Kohner of Paris in the early 1920s, “and I only have to close my eyes to bring it all back to me; the rich mixture of cigarette smoke, garlic, hot chocolate, fine a l’eau, burned almonds, hot chestnuts, and—all pervading—the strong scent of a perfume that had just become the rage of Paris—L’Heure Bleue.”

Kohner is correct in all but his timing. Jacques Guerlain first marketed L’Heure Bleue—The Blue Hour—in 1912. Its arrival on the market signified a fundamental change in the use of personal fragrances.

Perfumes had existed since Egyptian times. In the Middle Ages, the French, by virtue of their mastery of gardening and an intimate understanding of the flowers that grew around such southern cities as Grasse, became skilled at using steam and oil to isolate, extract and concentrate fragrances. The work was difficult and complicated. It took 440 pounds of lavender to produce 2.2 pounds of the extract used by parfumiers.

This skill flourished during the 17th century, when the Versailles of Louis XV became known as “the perfumed court,” but by the late 19th century, for any woman to wear a scent other than delicate infusions of lavender or rose marked her as “fast,” while strongly aromatic musk-based perfumes were used almost exclusively by courtesans and prostitutes.

This changed early in the 20th century. Parfumier Jacques Guerlain, strolling on a summer evening by the Seine (or, in some versions of the story, along a country path), was struck by, in the words of a publicist, “the spectacle [of] nature bathed in a blue light, a profoundly deep and indefinable blue. In that silent hour, man is in harmony with the world and with light, and all the exalted senses speak of the infinite.”

Painters and photographers had long recognized the heure bleue—when daylight becomes dusk—as the moment when natural light is at its most flattering. And yet no distiller of fragrances, however masterful his technique, had ever claimed to capture anything so evanescent as atmosphere. What Guerlain saw in his moment of revelation was not so much a method of catching magic in a bottle as a way to make money.

L’Heure Bleue owed its existence to Jicky, developed by Guerlain’s uncle Aimé in 1889, and regarded as the first “modern” perfume in that it used essences created in the laboratory. One of the first odors successfully synthesized was vanilla. Both Jicky and L’Heure Bleue relied on synthetic ethylvanillin to bind a mixture of natural fragrances—among them, in the case of L’Heure Bleue, carnation, ylang-ylang, anise, orange blossom, iris, licorice, aniseed, bergamot, rose, tuberose and violet.

The marketing of L’Heure Bleue was as inventive as its fabrication. Guerlain enclosed a few ounces of the perfume in a molded and gilded flaçon of Baccarat crystal with a stopper representing an inverted but hollow heart. For women not accustomed to expensive perfume bottles, the container was as great a pleasure as the scent. The company used the same bottle for Mitsouko in 1919, emphasizing its grasp of the increasing and paramount importance of the container in selling perfume.

In 1920, couturier Coco Chanel entered the fragrance business, commissioning Ernest Beaux to create a Chanel scent. Formerly parfumier to the Russian court, Beaux used two synthetic aldehydes, one called Rose E.B., the other a man-made jasmine, Jasophore. Combined with iris root and other natural fragrances, they created a distinctive perfume that he presented to Chanel in phials numbered one to five and 20 to 24. She chose the fifth—less from any preference than because she believed five was her lucky number. “I present my dress collections on the fifth of May, the fifth month of the year,” she told Beaux, “and so we will let this sample number five keep the name it has already, it will bring good luck.”

Almost as much effort went into designing the bottle for Chanel No. 5 as into making the perfume. Instead of the baroque of Lalique and Baccarat, Chanel wanted a simplicity of material and form consistent with her dress designs; the perfume equivalent of her trademark “little black dress.” In some versions of the legend, she based the plain oblong container on the toiletry bottles in the Charvet traveling case of her lover, Arthur “Boy” Capel. In others, it was his whisky decanter that struck a chord. In a third version, she was inspired by the configuration of Place Vendôme, as seen from her suite at the Ritz Hotel.

Initially she sold No. 5 only through her French boutiques, but that soon changed. During the 1920s, the fragrance business was transformed due to the efforts of one man, François Coty. While he agreed with Guerlain and Chanel that packaging was paramount, he also believed that good design didn’t preclude mass marketing. “Coty perceived perfume as something in a lovely bottle rather as merely something lovely in a bottle,” wrote Janet Flanner. “He presented scent as a luxury necessary to everybody.”

An aggressive Corsican with a Napoleonic complex, Coty thrust himself into the perfume market in 1904 with a fragrance called La Rose Jacqueminot. Hawking it around Paris department stores, he had little success until, supposedly by accident, he smashed a bottle in the perfume department of one of the largest, Grands Magasins du Louvre. La Rose Jacqueminot wafted through the store. Within minutes, women were converging on the source and buying every bottle.

As a selling technique, smashing a bottle was inspired, opening the door to the modern technology of samplers and scented magazine inserts. Pressing his advantage, Coty hired glassmaker Rene Lalique to design his packaging. At the same time, he expanded into low-priced soaps, powders and eaux de toilette, and exported vigorously, in particular to the United States, with a range of powders and colognes scented with the fragrance L’Origan (oregano). Once women everywhere found they could enjoy L’Origan at a modest price, its round orange boxes with their Lalique design became world-famous.

Coty channeled his millions into politics. Virulently anti-Communist and anti-Semitic, he supported the rising Fascist movement and even formed his own paramilitary organization, Solidarite Française, with the intention of overthrowing the government. It expired with his death in 1934.

By then, mass-marketing of fragrances had become commonplace. The distinctive midnight blue bottles of Bourjois’ Evening in Paris were familiar worldwide. Even Chanel bowed to commercial inevitability and licensed her perfumes. In return for 70 percent of the income, the Wertheimer company launched No. 5 and other Chanel products onto the world market. Though they were phenomenally successful, it increasingly rankled with Chanel that she received only one percent of the gross income. When war broke out, she used the French government’s anti-Semitic laws in an attempt to overturn the contract. Shrewdly, however, the Wertheimers had reincorporated in Switzerland and appointed a Gentile general manager. After the war, she and the Wertheimers came to an agreement that made her one of the world’s richest women. Today, Chanel remains a privately held company owned by the Wertheimer family. Its annual income is $4.2 billion.

The increased popularity of fragrances for men further transformed the perfume industry during the 1930s. While some 19th-century perfumes, such as Guerlain’s Jicky, were aimed at both sexes, men avoided accusations of effeminacy by patronizing more robust “toilet waters,” “colognes” or “after shaves”: all diluted forms of perfume. A dash of Bay Rum, made from bay leaves and other aromatics macerated in alcohol, was considered manly, as was Old Spice, launched in 1938 and mass-marketed through the Boots pharmacy chain in Britain.

No manufacturer, however, produced the dream of all parfumiers—the scent that would drive men wild. In 1937, American parfumier Elizabeth Arden suggested her fragrances made women smell like a rolling Kentucky landscape, but “outdoorsy” didn’t appear to be the answer. Perfume historians Luca Turin and Tania Sanchez have proposed the most convincing theory yet. “After years of intense research, we know the definitive answer. It is bacon.”

Although the most comprehensive museums of perfume are in such centers of manufacture as Grasse, Paris has a number of attractive alternatives. Opened in 1914 and restored by decorator Andrée Putnam, Guerlain’s flagship boutique at 68, avenue des Champs-Elysées (8th) contains numerous reminders of the perfume industry during the 1920s and 30s. The Fragonard company maintains a museum of perfume in a 19th-century hotel particuliare at 9, rue Scribe (9th). Exhibits include a “perfume organ” of the kind used by parfumiers to compose new scents. Coco Chanel’s original boutique, opened in 1912 at 31, rue Cambon (1st), still operates. It was here that she presented all her collections, sitting on the spiral staircase, approving each model as she passed, and only descending at the close to accept the compliments of her admirers. Her private apartment on the top floor is not open to the public, but Karl Lagerfeld, who now controls the Chanel brand, has supervised the restoration of her suite at the Ritz Hotel on Place Vendôme (1st). It is available for $4300 a night.