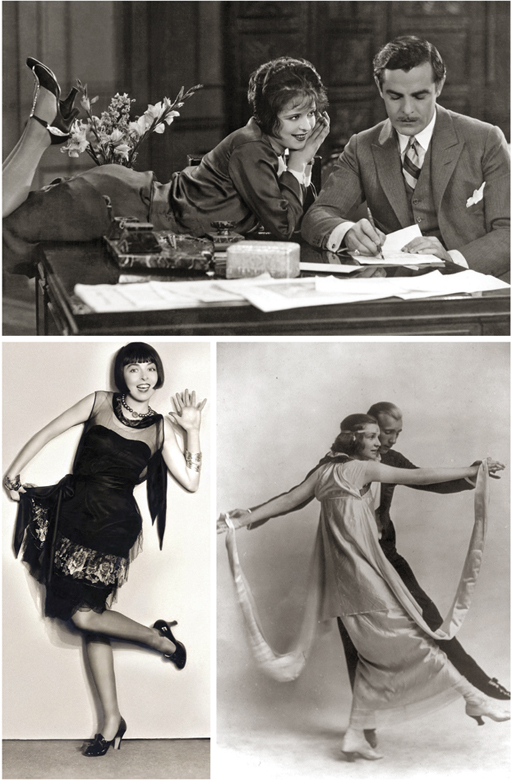

Top: Clara Bow in It (1927); left: Colleen Moore in Flaming Youth (1923); right: Irene Castle, c.1914

For women in the early 1920s, particularly in France, “bobbing” their hair by cutting it short was as blatant a symbol of revolt as putting a stud through one’s tongue or sporting a tattoo is today.

The appearance of a woman’s head took precedence over anything happening inside it. Nobody respectable went out in public without a hat. As for hair, it was her “crowning glory.” How she wore it signified social and sexual status. Young girls wore theirs either loose and flowing, or in braids. The moment when they were permitted to pin it on top of their heads signified adulthood. To “bob,” therefore, expressed contempt not only for style but the entire social order.

Top: Clara Bow in It (1927); left: Colleen Moore in Flaming Youth (1923); right: Irene Castle, c.1914

Rival styles of the bob cut were hotly discussed. Parted, or with bangs? Did one dare decorate the forehead with a “spit” or “kiss curl”? Hairpins became “bobby pins” as the vocabulary of the short haircut passed into the language.

Film stars were avatars of change. Clara Bow in It and Colleen Moore in Flaming Youth flourished their bobs like banners. Exhibition dancer Irene Castle, an arbiter of fashion, endorsed the cut. “In four cases at least that I know of,” she wrote, “it has been the making of a very individual and even beautiful person out of one who would not have attracted attention.” Scott Fitzgerald, who’d boasted “I was the spark that lit up flaming youth. Colleen Moore was the torch,” amplified Castle’s comment in his 1920 story “Bernice Bobs Her Hair.” Unattractive Bernice brings beaux flocking when she hints she’s contemplating a haircut, and suggests some lucky boy might be permitted to watch the scissors at work. In 1920, that was more piquant than the offer of a striptease.

It took the French, however, to turn the bob into a national scandal.

The vehicle of this fuss was La Garçonne, a novel by Victor Margueritte published in 1922. The heroine, Monique Lerbier, is a typical daughter of a prosperous family. Pushed into an engagement, she’s ready to do her duty—until she discovers her husband-to-be has a mistress. Eyes opened, she embarks on a life of excess. Stepping at random into a taxi, she offers herself to its passenger. They immediately check into one of the “hot sheet” hotels de passe that rent rooms by the hour.

She gets a job dancing nude in a club, flaunts elaborate costumes, including a peignoir trimmed with the plumes of the white ibis, experiments with opium, takes numerous lovers, including a female star of the music halls, and, in the ultimate act of defiance, has a child out of wedlock, whom she proposes to raise alone.

But before any of these, she first, symbolically, bobs her hair. The act announces her emergence as a new variety of individual—neither boy nor girl but a garçonne.

By adding “ne” to garçon, Margueritte feminized the word for “boy,” creating a new term, poorly translated in the American title for the book, The Tomboy. There was nothing masculine about les garçonnes. Though some were bisexual, affecting short haircuts and mannish suits, most didn’t dislike sex. Rather, they adopted an aggressive male attitude to it. A bob was their emblem of sexual and social liberation.

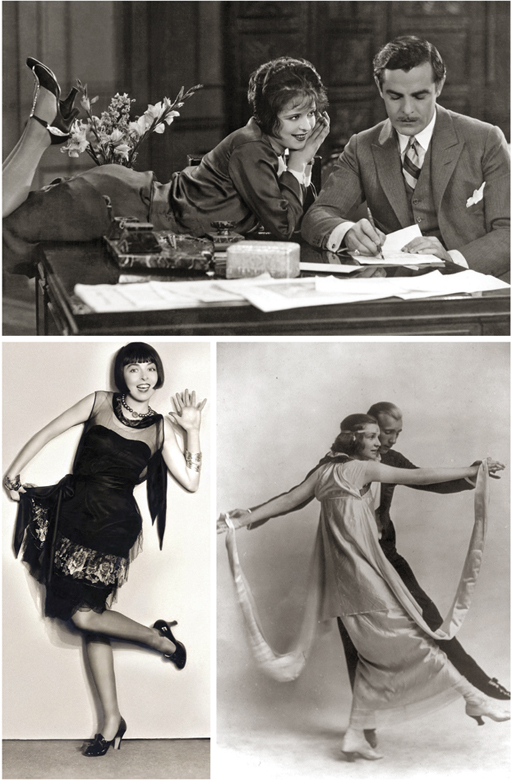

The archetypal garçonne was Fano Messan. Only 20 when Margueritte’s novel appeared, she had been apprenticed to a number of Montparnasse artists since she was 16. Described as “the youngest sculptor in the world,” she embraced the garçonne fashion without reserve, cutting her hair boyishly short and wearing an androgynous wardrobe. At the 1925 Salon d’Automne, she showed a piece called Androgyne, and was photographed standing next to it in a smock that hid everything. Lorimer Hammond reporting on the Paris art scene for the Chicago Tribune, wrote “The Latin Quarter amuses itself in trying to determine the sex of Fano Messan.”

When Man Ray photographed Messan, he went along with the joke. In one pose, even draped in a figured shawl, wearing a mannish sweater and with her hair severely bobbed, she’s obviously a girl. However, in a second pose, her body is obscured, making the question moot. When Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel cast her in their 1928 film Un Chien Andalou, they further confused things. Playing an androgynous pedestrian who pokes a severed hand with a stick, Messan is described simply as “The Hermaphrodite.”

Fano Messan, Emmanuel Sougez, 1921

Critics continued to attack the garçonne style as it spread through Parisian costume and behavior. The bob cut gave birth to cloche i.e., bell-shaped hats (unwearable over long hair) and the “Castle Band,” a bandeau over the forehead, in a style popularized by Irene Castle. Seeing a century of long hair and longer skirts swept away by rising hemlines, rolled stockings and general razzamatazz, some critics felt the devil was at the wheel.

Sociologists argued that, because of deaths during the war and the 1919 “Spanish flu” epidemic, France had 10 percent fewer eligible men. Women could no longer wait around in the hope of being selected. The doom-sayers dismissed this argument. One wrote sarcastically in 1929 “The old-fashioned ideas which so outrageously limited woman’s horizon have been done away with. Now she is able to taste life to the full. She can go to night clubs. She can rub elbows with thieves, gigolos, and prostitutes. She can paint like a prostitute, dress like a prostitute, get drunk like a prostitute. At last she is free, free! Night life has changed from a man’s sport to a woman’s sport. It is woman who is now most active in keeping it alive. It is she who cries, ‘Come on! Let’s go!’”

Victor Margueritte found himself embroiled in a social and political storm. Like Vladimir Nabokov when he wrote Lolita, he was an improbable agent of change. In his 50s, an established editor, essayist and occasional novelist, he had been awarded, for his services to literature, France’s highest civilian distinction, the Légion d’Honneur. Now all that was under threat.

The sexual experiment of La Garçonne’s heroine might have escaped censure were it not for her decision to have a child outside marriage. In deeply conservative family-oriented France, this was particularly divisive. Margueritte protested that his garçonne doesn’t remain in revolt. At the end of the novel, she meets a man worthy of her. Not only does he believe in female equality; he throws himself in front of a jealous lover intent on murder. Independence forgotten, Monique falls into his arms. But it was too late. The Archbishop of Paris denounced La Garçonne. Distributor Hachette withdrew the book from railway bookstalls, a major source of sales. And finally, in a sanction usually imposed only on criminals and traitors, Victor Margueritte was formally ejected from the Légion d’Honneur.

In the United States, the publication of La Garçonne inaugurated a rash of such “bobbing” novels as Maxwell Bodenheim’s Replenishing Jessica and Flaming Youth by “Warner Fabian”—actually humorist Franklin P. Adams. The moral majority responded much as it had in France. A New York grand jury tried to have H.B. Liveright prosecuted for publishing Bodenheim’s novel. The attempt fizzled out, since, after the first sensation, the bob cut was accepted as just another style. As the 1920s ended, wiser heads were wondering why there had ever been such a fuss.

In her 1931 film Shanghai Express, Marlene Dietrich plays a sultry adventuress exercising her charms along the China coast. When, by chance, she meets a former lover, he’s bitter about the time they lost. “There are a lot of things I wouldn’t have done if I had those five years to live over again,” he says morosely. But Marlene thinks not. “There’s only one thing I wouldn’t have done,” she says. “I wouldn’t have bobbed my hair.”

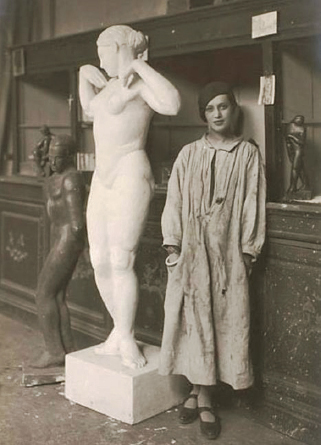

The most readily recognized bob belongs to the film actress Louise Brooks. When Louise was only 10, her mother, seeing the short haircut of Gloria Swanson, cut her daughter’s braids. Even in high school Louise wore her hair short, though flared out in the style known as a Page Boy or Dutch Girl. In 1928, playing a hobo in Beggars of Life, her disguise as a boy, in male suit, cap and short haircut, came close to the garçonne look. Once she achieved fame in the late 1920s, her haircut became more severe, developing into the trademark “raven helmet”—black, glossy, with straight-cut bangs across the forehead and two swerving wings across the cheeks, their points drawing attention to her expressive face with its wide eyes and questing pointed nose. A journalist of the time rhapsodized about Brooks’s “camellia skin, dark eyes, and black silky hair, lucid like a Chinese varnish.”

Brooks’s adoption of the bob mirrored the adventurousness of her private and professional life. Feeling undervalued in Hollywood, she moved to Europe in the late 1920s, taking daring roles as a prostitute and seducer in G. W. Pabst’s Diary of a Lost Girl and Pandora’s Box. She never resumed a Hollywood career, and died penniless, but because of her intransigence and, arguably, her haircut—immortal.

Louise Brooks