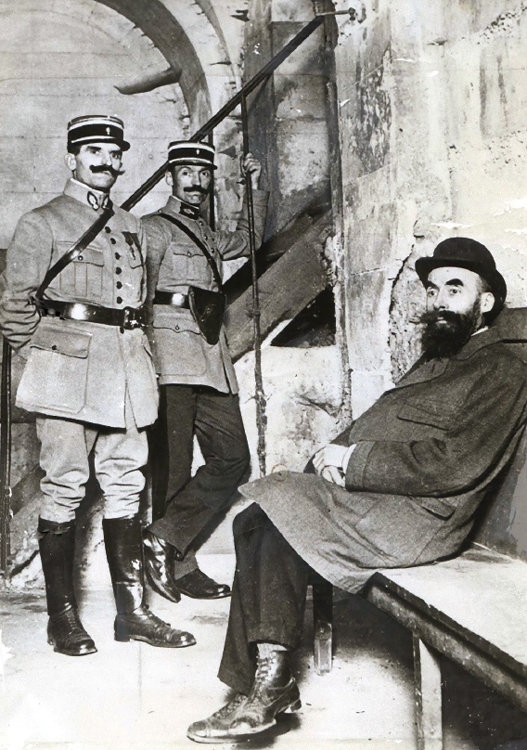

French serial killer, Henri Desire Landru (1869-1922), during his trial at Versailles in 1921

It is only a kitchen stove, solidly constructed of black iron, somewhat rusted, obviously much used. Uncommon, admittedly, in an auction sale such as this, of objects lost and found on the railways, or surplus to government requirements, but all the same, just a stove.

So why such a crowd at this sale in Versailles on the morning of January 23, 1923? Why all these journalists? And why the presence of a tall suave man in an expensive felt hat and a coat of glossy black Persian lamb?

Bidding on the stove begins at 1000 francs. The crowd is silent. Impatiently the auctioneer raises his gavel. “Going once for one thousand . . . going twice . . .”

“1500!” from the back of the room.

”2000!” from somewhere else.

A murmur runs through the crowd. Within seconds, the price has soared to 3700 francs.

“4200!”

It’s the man in the astrakhan coat. In awed silence, the stove is knocked down to him for 4200 francs—in today’s money US$6000.

As the buyer steps forward to pay, he’s recognized at last. M. Anglade, director of the Musée Grevin. Well of course! Who else would pay such a fortune but the proprietor of Paris’s most famous waxworks show? And perhaps it isn’t so much—for the stove of Henri-Desire Landru.

Before the war, Landru had been just another swindler, earning a modest living for his wife and four children, serving short prison terms for frauds as minor as stealing bicycles and supplying inferior materials to land surveyors. Once the war arrived in 1914 and the draft swept up most able-bodied men, the opportunities of a Paris filled with lonely women proved too tempting to resist. Landru began to murder.

His unwitting accomplices were the staff of Agence Iris, a company which, for a small fee, would insert personal ads in papers and magazines, and collect replies in private boxes. Before the war, illicit lovers, prostitutes and abortionists were its main clients. Business improved once it suggested that lonely women whose men were at the front might adopt another soldier as a marraine de guerre or “war godmother.” They could correspond with him, knit him sweaters and socks, and, when he was on leave, invite him to visit for . . . well, that was left discreetly unspoken.

Marraines de guerre was Agence Iris’s greatest success. By the end of the war, it had handled between 200,000 and 300,000 such advertisements. Amid so much correspondence, nobody noticed a dapper gentleman, always neatly dressed, or enquired why he needed three boxes to handle the replies—until they found that he used 90 different names and responded to 283 women, ten of whom disappeared shortly after. A few worried relatives reported them missing, but the police, overstretched in wartime, gave a low profile to missing persons. A shortage of men had opened the market for female bus drivers, factory workers, shop assistants and nurses. It wasn’t unusual for single women to change addresses without notice.

Landru always placed the same advertisement. “Widower with two children, aged 43, with comfortable income, serious, and moving in good society, desires to meet widow with a view to matrimony.” The appeal was instant. Women liked his business-like style, the promise of someone solid, reliable. And in person Landru didn’t disappoint. True, he was short, and billiard-ball bald, but thick eyebrows and a flowing beard of deep mahogany red gave him a commanding air. He looked the model of what his victims craved; a serious man.

Shrewdly, he met his prospects in public places; railway stations, parks, particularly the Luxembourg Gardens. No out-of-the-way hotels or suburban cafés, but lawns with strolling couples, nurses with baby carriages, a brass band, and an old woman collecting payment for the use of the chairs. What could be more innocent?

Landru checked each woman in person. Some he discarded. Many he seduced. One has to admire his systematic approach, not to mention his stamina. A typical schedule for 19 May 1915 read:

9.30. Cigarette kiosk Gare de Lyon. Mlle. Lydie.

10.30. Café Place St. Georges, Mme. Ho.----

11.30. Metro Laundry. Mme. Le C-----

14.30. Concorde North-South. Mme. Le -----

15.30. Tour St. Jacques. Mme. Du----

17.30. Mme. Va.----

20.15. Saint Lazare. Mme. Le ----

Just as tireless in the bedroom, he passed his evenings with a succession of these women in one of the seven city and four suburban apartments he rented under aliases. If one can believe sketches he made of himself while in jail, he possessed a lengthy penis, and was expert in its use. Most women probably never asked about his business. To those who did, he claimed he had been in aviation before the Germans seized his factories. If pressed, he would describe his product, a variation on the whaling harpoon, meant to skewer fighter planes in mid-air. (The Air Force actually experimented with such a weapon, but found it too heavy.)

Sometimes Landru’s conquests were simply romantic, but the 10 women he murdered, all widows, had money, and were prepared to sign it over in return for a respectable marriage. His modus operandi seldom varied; a proposal, the opening of a joint bank account into which his new fiancée deposited her savings as the traditional dot or dowry; then an invitation to spend the weekend before their wedding at his country home in Gambais, 60 miles west of Paris. The following week, he returned, alone, emptied the account, removed her possessions to his warehouse, and visited Agence Iris to clear his boxes.

The friend of a vanished widow finally recognized Landru in the street and followed him home. Even on the stand, he inspired belief. Cartoonists represented him as a stage magician, inviting ladies to step up from the audience and take part in his performance. He dressed so well that a wit suggested the court record note “When in town and on trial, M. Landru buys his clothes from the High Fashion Tailor.” In an election that took place during his trial, he received 4000 write-in votes.

The police charged that Landru killed his victims, dismembered them, and cremated their bodies in the kitchen stove. But where was the evidence? No body ever came to light. Neighbors at Gambais talked of a stove burning late and oily black smoke streaming low over the fields. But sieving the ashes produced only 256 fragments of bone, a few metal buttons and catches of the kind used in women’s corsets. Also found in the house were containers of acid that could have dissolved those parts of the corpses not burned.

Under French law, a juge d’instruction both leads the investigation and tries the case. A.M. Bonin, the judge assigned to Landru, had a rough ride. Grey-haired, patient and precise, a collector of art, he was no match for his puckish suspect. After Bonin laid out his case, Landru dismissed it as “a load of rubbish.” Looking around the judge’s office, filled with nude bronzes signed “Rodin,” Landru informed him confidently that they were all fakes. (He seems to have been right. Shortly after Auguste Rodin died in 1917, the Montagutelli brothers, his plaster casters and bronze founders, were accused of making illicit copies.) He continued to mock Bonin throughout the trial, even sending him a self-portrait of himself naked, with a large erection.

Landru was caught not by forensic evidence but a simple error of thrift. As a conscientious businessman, he recorded every expense—right down to the railway tickets between Paris and the station nearest to Gambais, Tacognieres. Reading through these records, the police saw a disparity in the case of Louise-Josephine Jaume. In June 1917, she accompanied Landru to Gambais. He had noted the costs. Single ticket to Tacognieres—2 francs 75 centimes. Return ticket—4 francs 40 centimes.

Why buy only a single ticket for Mme. Jaume? How was she expected to return to Paris? Landru had no answer. Convicted on all counts of murder, he was executed by guillotine at Versailles in February 1922.

Though Landru’s house at Gambais still stands, it’s a private home and there is no access. His stove, after being placed on show at the Musée Grevin, was sold to an American collector. Its present whereabouts are unknown. Executed felons were buried in the yard of the prison where the sentence was carried out. However the Museum of Death, 6031 Hollywood Blvd, Hollywood, California, displays an object that they claim to be Landru’s severed head. Its provenance is obscure. Materials on the trial of Landru are on show at the Musée de la Préfecture de Police, 4, rue de la Montagne-Sainte-Geneviève (5th).

The outdoor cafés in the Luxembourg Gardens where Landru often arranged to meet his victims have not changed much in the hundred years since.

Landru’s house in Gambais