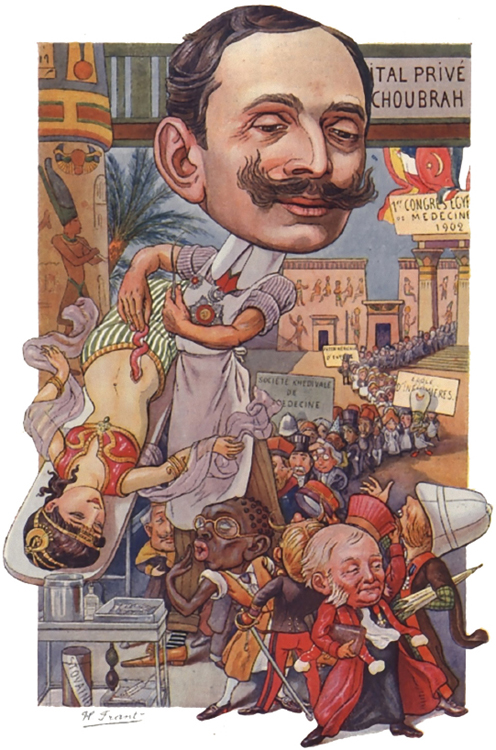

Dr. Samuel Serge Voronoff, Cairo-Romainville: Laboratory Carnine Lefrancq, 1910

Following the medical advances of World War I and research in Austria and Germany during the early 1920s, scientists began to explore the possibility of extending human life and reversing the effect of the years, compared by poet W.B. Yeats to “great black oxen [that] tread the world, And God the herdsman goads them on behind, And I am broken by their passing feet.”

Noting how virility and desire decrease with age, researchers concentrated on the reproductive system. In Vienna, Eugen Steinach claimed good results by bombarding ovaries with X-rays. “We cannot perform the comic opera bouffe of transmuting an old hag into a giddy young damsel,” he wrote. “But, under certain conditions, we can stretch the span of usefulness, and enable the patient to recapture the raptures, if not the roses of youth.” He promised similar good results for men by giving them vasectomies, believing that seminal fluid would back up into the system, rejuvenating it. Satirist Karl Kraus welcomed this news. Steinach, he suggested, might be able to revive the feminine in suffragettes and turn journalists into real men.

One of Steinach’s patients, Californian novelist Gertrude Atherton, hailed the treatment, which returned her to “renewed mental vitality and neural energy.” Working at record speed, she wrote Black Oxen, in which a middle-aged playwright discovers that an apparently young countess is actually a 58-year-old woman he romanced 30 years before. The countess explains that the Steinach treatment has restored 30 years of youth, with the promise of even more. “Eminent biologists who have given profound study to the subject estimate that it will last for 10 years at least, when it can be renewed.” Atherton using a title from Yeats had a poetic significance, since in 1934, when he was 69, Yeats submitted to the Steinach treatment in London. To test its effectiveness, his surgeon invited him to dinner with an attractive woman, and left them alone afterwards. Yeats became a convert. “It revived my creative power,” he said. “It revived also sexual desire; and that in all likelihood will last me until I die.” Dublin celebrated him as “a gland old man.”

As Atherton was 66 when Black Oxen appeared in 1923 and survived to 92, she might have appeared a living advertisement for the Steinach treatment—except that Yeats lived only another five years after his surgery. Suspicions also grew of dangerous side-effects. In 1924, the film Vanity’s Price, from a screenplay by Paul Bern, showed a woman rejuvenated by Steinach therapy who goes insane as a result. In Conan Doyle’s 1923 The Adventure of the Creeping Man, Sherlock Holmes investigates the erratic behavior of a professor who, about to marry a younger woman, takes pills to rejuvenate him, which instead change his personality.

By then, the center of rejuvenation therapy had shifted from Vienna to Paris, where Russian-born surgeon Serge Voronoff had arrived from Egypt to open a clinic. Voronoff, formerly personal surgeon to the Khedive or viceroy, had pioneered bone grafts and worked with distinguished physician and author Alexis Carrel. Investigating the body’s rejection mechanism, he injected himself with a solution of sheep testicles, hoping it would retard aging. When it failed, he turned in 1920 to grafting minute portions of bull or monkey testicles into human scrotums. Most of his patients, some of them physicians, claimed immediate and sustained increases in energy and sexual virility. Within a decade he had treated more than 500 men, some with injections, others with transplants.

Injections or transplants from animal glands became a fad; there was even a cocktail called The Monkey Gland. Ashtrays appeared in France showing monkeys clutching their testicles and screaming “Not me, Dr. Voronoff!” Voronoff told the American press in 1922, “already I am using four different glands from every chimpanzee received from Africa, notably thyroid glands for weak-minded children and interstitial glands for rejuvenation of the aged. The chimpanzee is the only species of monkey that can be used, it being wonderfully like a human being. The organs are identical and the bloods are indistinguishable. Chimpanzees now cost $500 each.”

In California, Dr. Clayton E. Wheeler gave 12,000 goat gland injections to patients between the ages of 52 and 76. “The human body is just like a storage battery of a motor car or radio,” he explained. “Its potency ebbs with use and needs to be reinvigorated at certain intervals to restore its customary vitality.” In June 1922, The New York Times wrote, “In the last two years, the reading public has become pretty well accustomed to the almost continuous hysterical manifestations of concern for its glandular welfare. A war-ridden world has given way to a gland-ridden world. Nearly every newspaper and magazine that one picks up contains some reference—jocular or serious—to monkey glands and goat glands and the beneficent possibilities in human gland nurture and repair.”

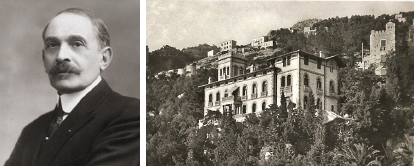

In 1923, 700 surgeons at the International Congress of Surgeons in London applauded Voronoff. Patients flocked to him, including the president of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. He operated three clinics around Paris, all in fashionable areas: at Villa Molière in Auteil, the Ambroise Paré nursing home in Neuilly, and on fashionable Avenue Montaigne. He also opened another in Algiers. When the French government forbade the trapping and importation of apes in 1923, he started two monkey farms to breed chimpanzees and baboons, one at Nogent-sur-Oise in the northern region of Picardie, the other in the Villa Grimaldi at Menton, which straddled the French Italian border. The mountainside estate with its giant cages became famous. Voronoff entertained numerous celebrities there, including Russian impresario Serge Diaghilev and soprano Lily Pons, who was a regular visitor.

In 1930, Einar, husband of the Paris-based illustrator Gerda Wegener, underwent the world’s first sex reassignment operation in Berlin. A year later, now Lily Elbe, she submitted to further surgery to implant a uterus, which would have enabled her to have children. Instead, her body rejected the organ, and she died. Inspired by this, Voronoff transplanted a human ovary into a female monkey named Nora, and attempted to inseminate it with human sperm. That experiment also failed.

By this time, research into the male hormone testosterone was casting doubt on the methods of Steinach and Voronoff. Investigators examining what their recipients believed were still viable grafts, secreting hormones into their system, found only scar tissue from the implant surgery. All primate tissue had long since been rejected. Any supposed new potency and energy was self-delusion.

Serge Voronoff (1919) and Villa Grimaldi at Menton

Voronoff had already begun distancing himself. In 1939 he gave up all his research facilities in Paris and left for a tour of the United States, Brazil and the Argentine arranged by the Franco-Ibero-American Medical Union. After the outbreak of war in 1939, it was no longer prudent to return to Europe. He remained in America until 1945, by which time the Villa Grimaldi had been badly damaged by bombing and all his Paris clinics were shut down.

By the time Voronoff died in 1951 at the age of 85, few noted his passing. He was buried quietly in the Russian section of the Caucade Cemetery in Nice. Most physicians denied they had ever supported him or used his methods. It was even suggested that, in transplanting ape organs into man, he may have unwittingly transferred the AIDS virus, though no evidence exists to support this contention.

A few physicians remained convinced. In particular Dr. Paul Niehans, a Swiss doctor, established a clinic to inject animal cells into humans. His patients included Pope Pius XII, King Ibn Saoud, German President Konrad Adenauer and such film stars as Charlie Chaplin and Noel Coward. Noting that the herd of sheep used by the clinic included a single black one, Coward quipped “I see the doctor is expecting [African-American singer] Paul Robeson.”

Gertrude Atherton was not the last person to see the dramatic possibilities of rejuvenation. H.G. Wells’s 1896 novel The Island of Doctor Moreau takes place on a Pacific island where a doctor uses surgery to create creatures that are part animal and part man.

Voronoff’s apparent success, combined with the popularity of such novels as Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan of the Apes, in which an English orphan is raised by monkeys, fed the fantasy that apes and men could socialize, and even interbreed. In 1930, novelist Félicien Champsaur wrote Ouha, Roi des Singes, (Ouha, King of Apes). In it, an American scientist educates an exceptionally intelligent monkey from Borneo to become “the Napoleon of Apes,” only to see him destroyed when he falls in love with the scientist’s daughter, a prefiguring of King Kong. Champsaur followed with Nora, la guenon devenue femme (Nora, the Monkey Turned Woman). Suggested by Voronoff’s experiment of ovary transplant but directly inspired by the arrival on the Paris stage of part-African American performer Joséphine Baker. In a racist speculation typical of the era, it proposed that Nora did produce a daughter, a combination of human and ape that grew into Baker.