Eric Liddell is paraded around Edinburgh University after winning the 400 metres at the 1924 Paris Olympics.

But for a film sequence of barefoot young athletes running in slow motion along a beach to the music of Vangelis, few people would know or care about the 1924 Olympic Games in Paris. But in dramatizing the events behind the running of the 100 meters final, Hugh Hudson’s 1981 movie Chariots of Fire cast a tantalizing sideways light on the social, political, nationalist, financial and religious forces that would come to dominate sports.

After the disastrous 1900 Olympiad in Paris, marred by squabbling among rival ruling bodies, flagrant cheating, and an eccentric selection of sports (balloon racing; croquet; pigeon shooting with live pigeons), Baron Pierre de Coubertin hoped the 1924 games, his last, would dignify the movement he launched. Though Amsterdam had already been chosen over Barcelona, Los Angeles, Rome and Prague to play host, the Baron, about to step down from leadership, pleaded that Paris deserved a chance to redeem the 1900 debacle.

Eric Liddell is paraded around Edinburgh University after winning the 400 metres at the 1924 Paris Olympics.

In practice, the events of 1924 came close to eclipsing it.

Foreshadowing the political agendas that would lead to the 1980 U.S. boycott of the Moscow games and the U.S.S.R.’s reciprocal withdrawal from Los Angeles in 1984, the American government used the 1924 Olympics to play politics. On the eve of the games, the United States strongly censured France for having invaded Germany’s rich industrial Ruhr area in an effort to extract unpaid war reparations. Paris crowds cursed and spat on American athletes. Ironically, the country at the center of the controversy, Germany, was not invited to compete.

America’s rugby footballers suffered particularly violent abuse. Included for the first time in the games, rugby promised an easy gold medal for France, a world leader in the sport. The U.S. team, after being initially refused admission to France, then denied practice space, insulted in the press, and robbed of money and valuables, met France on May 18th in what was manifestly a grudge match. After French star Adolphe Jaureguy was carried off unconscious with a broken nose, local fans turned on American spectators in the crowd and beat them senseless, then watched stone-faced as their limp, bloodied bodies were passed over their heads to ambulances on the field. When the visitors won 17-3, French supporters rioted. Had police not erected new metal fences in expectation of trouble, the Americans might not have survived. As it was, the roar of protest and abuse was so great that it drowned out the playing of the U.S. national anthem during the award ceremony.

A quieter revolution was taking place in the British athletic team. Harold Abrahams and Eric Liddell were rivals in the 100 meters until Liddell learned that the final would be run on a Sunday. A devout Christian who later became a missionary in China, he refused to compete on the Sabbath. Withdrawing from the 100 meters before the Games, he began retraining for the 400 meters. Abrahams won the 100 meters, but Liddell, against all expectations, took the 400 meters in world-record time.

Britain also figured in a boxing scandal. Harry Mallin, defending middleweight champion, met Frenchman Roger Brousse in the quarter-finals. As the bout ended, Mallin protested to the referee that Brousse had repeatedly bitten him. He was ignored, and the decision awarded to Brousse on points. However, when Argentina’s Manolo Gallardo also complained of being bitten, a Swedish official demanded an inquiry. Brousse claimed he snapped his teeth together when he threw a punch, and that Mallin and Gallardo had simply bumped him at the wrong time. The jury decided the Frenchman didn’t bite intentionally, but still disqualified him. At the final bout two days later, Brousse, wearing gloves and trunks, appeared with a mob of fans who, in the midst of uproar, boosted him into the ring with Mallin and his opponent. Police had to be called to remove Brousse and his supporters. Mallin went on to win.

When de Coubertin revived the Olympic Games in 1896, he included a medal for mountain climbing. It was awarded for the first and last time in 1924, to the members of a 1922 British team that had attempted to scale Mount Everest. They came within 500 meters of the summit, but failed three times to reach it. Britain mounted another expedition in 1924. A member, Lieutenant Colonel Edward Strutt, came to Chamonix to accept 13 silver-gilt medals, one for each British member of the party. He pledged that, if possible, one would be placed on the summit. Unfortunately the expedition not only failed to conquer the mountain; seven Sherpa porters died in an avalanche. The Olympic body hastily minted eight more medals, and presented them to the one surviving Nepalese and the grieving families of the others. Strutt’s pledge wasn’t honored until 2012, when a team financed by the electronics giant Samsung placed one of the medals on the peak.

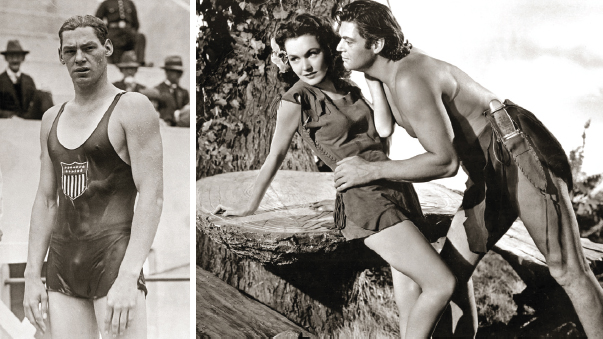

The 1924 games did produce some notable victories. Johnny Weissmuller, later Hollywood’s Tarzan, took three gold medals in swimming, and Benjamin Spock, destined to write some classic works on child care, rowed in the triumphant eights crew. In the final medal tally, the United States led with 45 gold, followed by tiny Finland with 38. The host nation, France, trailed humiliatingly with 37, though well ahead of Britain’s nine.

Finland owed its triumph to one man, distance runner Paavo Nurmi. Known as The Flying Finn, he put on an exhibition of disciplined physical achievement that not only won personal gold but inspired his national team to victory. Running with a stopwatch on his wrist, Nurmi won the 1,500 and 5,000-meter finals within an hour of each other, and set Olympic records in both. Two days later, he won the 10,000-meter cross-country run after a tough course and blistering heat caused 23 of the 38 starters to drop out.

Johnny Weissmuller won three Olympic gold medals in 1924 and enjoyed a successful acting career as Tarzan

Nurmi’s sportsmanship shamed the cheats who dominated the 1924 games. The Olympiad concluded with many believing there would never be another. Aside from the numerous abuses, it was a financial disaster, earning only 5.5 million francs of the 10 million francs it cost. The Times of London called its report “the funeral oration of the Olympic Games; not of these particular Games only but of the whole Olympic movement.” It continued “The ideal which inspired the re-birth of the Games was a high one—namely by friendly rivalry and sport to bind together the youth of all nations in a brotherhood so close and long that it would form a bulwark against the outbreak of all international animosities. But the world is not yet ripe for such a brotherhood.” That the Olympic movement survived not only the scandals of 1924 and such politically motivated games as those staged in Berlin in 1936 but also repeated cases of corruption and incompetence within its own ranks is proof, if not of international brotherhood, then of the enduring and passionate desire of mankind to watch others strive, in the motto of the Games, to be “faster, higher, stronger.”

Because of a shortage of venues, events were more widely dispersed in 1924 than in modern Olympiads. Sailing took place on the English Channel at Le Havre and clay target shooting at the satellite town of Issy-les-Moulineaux. The primary venue was the Stade Olympique in Colombes, 10 kilometers north-west of central Paris. It hosted the athletics, certain cycling and equestrian events, all the gymnastics and tennis, some of the football and rugby, and the running and fencing heats of the modern pentathlon. The stadium still stands, although many features, including its concrete grandstands, have been demolished for safety reasons, reducing its original 45,000-person capacity to about 14,000.

Two other 1924 venues were also demolished: the Stade Bergeyre near Parc des Buttes Chaumont, site of some rugby matches, and the Velodrome d’Hiver or winter bicycle track, a covered auditorium used for boxing, fencing, weight-lifting and wrestling events. The “Vel d’Hiv” stood at the corner of rue Nélaton (15th). It became notorious during World War II when French police imprisoned Jews there awaiting deportation. The building burned in 1959. A plaque marks the site.