Few sportsmen figure among Nobel laureates, and even fewer in the literature category. An exception was Ernest Hemingway, who, with mixed success, tried big game hunting, sport fishing, skiing, bullfighting and, most tenaciously, boxing.

The painter and writer Percy Wyndham Lewis, calling on his friend poet Ezra Pound in the late 1920s, wrote “A splendidly built young man, stript to the waist, and with a torso of dazzling white, was standing not far from me. He was tall, handsome and serene, and was repelling with his boxing gloves—I thought without undue exertion—a hectic assault of Ezra’s. After a final swing at the dazzling solar plexus (parried effortlessly by the trousered statue) Pound fell back upon the settee. The young man was Hemingway.”

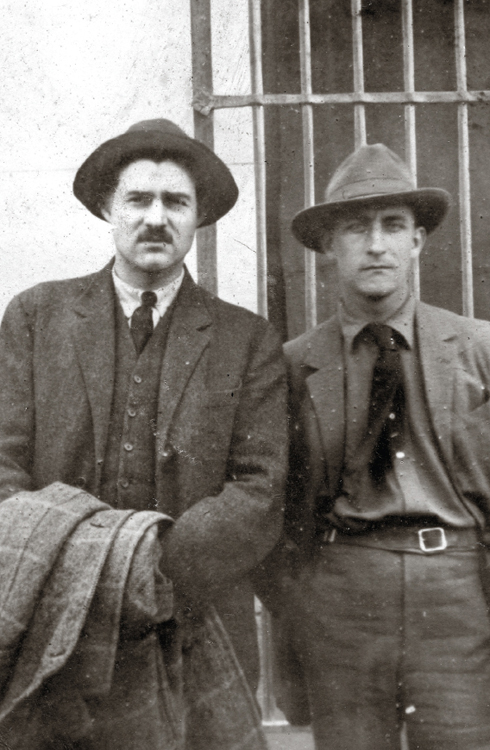

Hemingway could easily defend himself against a vigorous amateur like Pound but he met his match in a bloody encounter in 1929, for which, improbably, Scott Fitzgerald kept time. His opponent was Morley Callaghan, a Canadian writer with whom he had worked on the Kansas City Star. An admirer, Callaghan arrived in Paris and immediately looked up his former colleague. They were soon drinking together in such Montparnasse haunts as the Dingo Bar, where Hemingway and Fitzgerald first met.

Callaghan and Hemingway sparred and rough-housed around the large apartment on rue Ferou, which Ernest occupied with his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer. Even in play, he didn’t pull punches. Callaghan recalled, “My wife remembers how, when I came home, she would complain that my shoulders were black and blue. Laughing, I would explain that she should feel thankful; the shoulder welts and bruises meant Ernest had always missed my jaw or nose or mouth.”

Increasingly sensing Callaghan as a rival, Hemingway challenged him to a real fight. Even though Callaghan was a foot shorter and 25 pounds overweight, he agreed. “He had given time and imagination to boxing,” he said of Hemingway. “I had actually worked out a lot with good fast college boxers.” Hemingway relied on his height and weight. But Callaghan, a skillful and seasoned boxer, knew that fast footwork and accurate punching will wear down a larger opponent.

Though, later, Hemingway spoke of a single clash with Callaghan, there were several, spread over the winter of 1929. In earlier bouts, Callaghan proved his skill, ducking Hemingway’s punches while landing most of his own. One blow split Hemingway’s lip. They boxed on for a few seconds. Then Ernest lowered his gloves and spat a mouthful of blood into Callaghan’s face. “That’s what the bullfighters do when they are wounded,” he said conversationally. “It’s a way of showing contempt.” Wiping away the blood, an astonished Callaghan wondered “out of what strange nocturnal depths of his mind had come the barbarous gesture.”

Some weeks later, Hemingway proposed a rematch. Expecting they would once again spar informally for half an hour, Callaghan was surprised when his friend arrived at his apartment with Scott Fitzgerald, who had agreed, explained Hemingway, to act as timekeeper.

That Hemingway would invite the much less sporty Fitzgerald to officiate at a boxing match was almost as unlikely as him accepting, since the only exercise taken by the Great Gatsby author was to lift a glass. His acquiescence reflected a complicated relationship with Hemingway. As Norman Mailer wrote, “Fitzgerald was one of those men who do not give up early on the search to acquire more manhood for themselves. His method was to admire men who were strong.” Fitzgerald may have believed that, if he could not face his hero in combat, he could at least take part as a helper.

For his part, Hemingway probably wished the reverse: to destroy the intimacy they had built up. He had already told Callaghan he was avoiding Fitzgerald because he was a drunk and a nuisance. Other expatriates hinted at a more devious motive. Robert McAlmon, homosexual proprietor of the Contact Press, which published Hemingway’s first book, circulated a rumor, entirely unsubstantiated, that Hemingway and Fitzgerald were secret lovers. The suggestion would have repelled the ultra-masculine Hemingway, who may have seen the fight as a way to reaffirm his macho reputation.

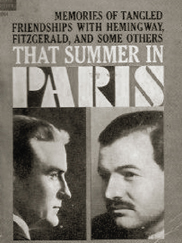

That Summer in Paris, Morley Callaghan, 1963

F. Scott Fitzgerald, 1921

A taxi took the three men to the American Club, which used the premises of the American Chamber of Commerce. There was no gym; just a basement with a ring marked out on the cement floor. Demonstrating that he took the bout seriously, Hemingway had brought heavy professional boxing gloves. Before he and Callaghan put them on, Hemingway coached Fitzgerald on the duties of the timekeeper—mainly to call “Time” at the end of each three-minute round.

Callaghan sensed that Hemingway regarded this bout as in some way a title fight to humiliate both Fitzgerald and Callaghan, and establish his supremacy both as writer and man of action. If so, he was disappointed. Within a minute of the first round, Callaghan scored solid blows on his opponent’s face. When Fitzgerald called “Time” to end the first round, Hemingway was flushed and his lip swollen.

In the second round, Callaghan bored in, punching hard. Hemingway’s lip began to bleed again. Fearing that he would again spit blood in his face, Callaghan swung hard and knocked him to the floor.

“Oh my God,” Fitzgerald said as Hemingway lay dazed. “I let the round go four minutes.”

Climbing to his feet, Hemingway said furiously, “If you want to see me getting the shit knocked out of me, just say so. Only don’t say you made a mistake.” He stormed away to take a shower.

“I could only stare blankly at Scott,” said Callaghan, “who, as his eyes met mine, looked sick. Lashing out with those bitter, angry words, Ernest had practically shouted that he was aware Scott had some deep hidden animosity toward him.”

To Callaghan, the issue looked more complicated. “Is the animosity in Scott,” he wondered, “or is it really in Ernest?” Perhaps, in Hemingway’s mind, the contender for the literary championship of Montparnasse was not Callaghan but Fitzgerald.

Some months later, Callaghan returned to Canada. The story might have ended there, as just another Montparnasse anecdote, had a journalist not written a garbled version of the bout for the New York Herald Tribune. It suggested that Hemingway had disparaged Callaghan’s work, and that Callaghan challenged him to a match and knocked him out.

Stung, but too proud to respond in person, Hemingway bullied Fitzgerald into protesting on his behalf. Fitzgerald cabled Callaghan “HAVE SEEN STORY IN HERALD TRIBUNE. ERNEST AND I AWAIT YOUR CORRECTION.” Callaghan denied leaking the story. He did, however, write to the Herald Tribune, setting the reporter straight.

Hemingway remained unsatisfied. “To be knocked down by a smaller man,” wrote Norman Mailer, “could only imprison him further into the dread he was forever trying to avoid.” In a letter to Callaghan, Hemingway admitted egging Fitzgerald into demanding a retraction, but at the same time tried to keep the feud going. “If you wish to transfer to me the epithets you applied to Scott,” he wrote stiffly, “I will be in the States in a few months and am at your disposal.” Even more surprising, he suggested a rematch. It had been an error to use heavy professional gloves, he said. “I honestly believe that with small gloves I could knock you out inside of about five two-minute rounds.”

Callaghan was too respectful of his old friend to take the bait. Thereafter their relationship deteriorated. For the rest of his life, Hemingway systematically rewrote his account of the fight. In a letter to his editor Maxwell Perkins, he claimed he had been drunk. “I had a date to box with [Callaghan] at 5 p.m.—lunched with Scott and John Bishop at Pruniers—ate Homard thermidor—all sorts of stuff—drank several bottles of white burgundy. Knew I would be asleep by five . . . I couldn’t see him hardly—had a couple of whiskeys en route . . . ”

In the same letter, Hemingway suggested Fitzgerald let the crucial round go not for four minutes but eight. By 1951, describing the incident to Fitzgerald’s biographer Arthur Mizener, the figure had risen to 13. He would rewrite his entire experience of Paris in the same way. Finally, the posthumous A Moveable Feast, heavily fictionalized, disparaged Fitzgerald as “poor Scott,” a pathetic drunk in thrall to a mad, malicious Zelda. The memoir left Hemingway the last man standing, undisputed heavyweight champion of Montparnasse.

All his life, Hemingway required male friends to prove their manhood by taking a physical risk. During a visit to Spain, he shoved Donald Ogden Stewart, his model for Bill Gorton in The Sun Also Rises, into a ring with a young bull. His fiction consistently showed bullfighters, hunters and game fishermen as figures of sexual potency. In “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” an amateur hunter in Africa shows cowardice when charged by a lion. Contemptuous, his wife sleeps with the professional hunter leading the safari. When the husband redeems himself by facing down a buffalo, she shoots him—whether by accident or design isn’t clear.

About boxing, Hemingway was boastful to a degree that shook his compatriots. He startled novelist Josephine Herbst by saying “My writing is nothing. My boxing is everything.” Before challenging Morley Callaghan, he had already boxed with Ezra Pound and Harold Loeb, who inspired the character of Robert Cohn in The Sun Also Rises—an incident used in the novel. Boxing also appears in such short stories as “Fifty Grand” and “The Battler.” In later years, he built a ring at his Key West house. When locals protested his success in game fishing tournaments, he invited them to settle matters in the ring, and supposedly knocked down all comers.