When F. Scott Fitzgerald published his fourth novel, Tender Is the Night, in 1934, it was already an elegy for a lost time. Its story of Dick and Nicole Diver, an American couple living in the south of France, and the decline of their relationship as Nicole descends into insanity, mirrored not only the personal lives of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald but also the way in which the indolence and excess of les années folles exposed character flaws in even the most well-meaning Americans.

The parallels between the Divers and a real American couple, Gerald and Sara Murphy, were not lost on other expatriates, least of all on the Murphys, who resented being maligned by a man who had been their friend and house guest.

Gerald’s family owned Mark Cross, which manufactured and sold luxury leather goods. However, like Harry Crosby and a few other wealthy Americans, Murphy shunned business. He volunteered for the army in 1918, but the war ended before he could fight. He studied landscape architecture for a time before deciding to relocate in France. In 1922, he encountered the Cubism of Picasso, Braque and Gris in a Paris gallery. “There was,” he wrote later, “a shock of recognition which put me into an entirely new orbit.” He told Sara, “That’s the kind of painting that I would like to do.” Both studied painting with Natalia Gontcharova, and Gerald began to paint the first of only 14 canvases he completed. Meticulously austere macro- or micro- studies of such inanimate subjects as the superstructure of an ocean liner or the interior of a watch, they attracted respect but also charges that they were little better than technical drawings.

The Murphys took to Paris as passionately as the city adopted them. Through Gontcharova, they met Serge Diaghilev. When the sets of the Ballets Russes were damaged in a fire, they helped repaint Leon Bakst’s backcloth for Scheherezade and Picasso’s for Parade. Picasso came to assess the repairs, and immediately became their friend. It’s suggested that Picasso and Sara became lovers, but she may simply have been one of his numerous infatuations. On the other hand, Picasso did, around this time, paint a number of studies of anonymous women, which might be secret portraits of her.

Fitzgerald dedicated Tender Is the Night “To Gerald and Sara —Many Fêtes,” a tribute to the couple’s delight at a party. To mark the production of Stravinsky’s Les Noces, the Murphys staged a famous celebration on a barge moored on the Seine. When no flowers could be found to decorate the tables, they created centerpieces of toys. The evening culminated in Stravinsky taking a running dive through one of the giant wreaths created to hang above the festivities. For Count Etienne de Beaumont’s Automotive Ball in 1924, Sara created a dress from metal foil, adding outsized driving goggles. Gerald, a tireless show-off, based his costume on a metal breastplate that had to be welded onto his body. He added tights, gauntlets, a helmet that echoed the architecture of Russian constructivist Vladimir Tatlin, and—the final touch—a rearview mirror attached to his shoulder.

In 1923, through his friend the painter Fernand Léger, Murphy was commissioned to design a ballet for the Ballets Suedoise. To write the music, he chose his Yale classmate Cole Porter. Within the Quota tells the story of a Swedish emigrant who goes to America in hopes of becoming a movie star. Murphy’s giant backdrop showed the front page of a fake newspaper, The New York Chicagoan. Copies of a parody issue were handed out to audiences.

Unexpectedly, the Murphys made their reputation not in Paris but on the Riviera. Until the early 1920s, the only foreigners to visit the Côte d’Azur came from such chill northern countries as Russia. Crown princes and their retinues waited out the winters there, returning to St. Petersburg in April or May, leaving the Riviera to fishermen and the occasional artist. During these sojourns, nobody swam, and everyone, particularly ladies, shunned the sun: a tan showed you were a peasant, forced to work outdoors.

All that changed in November 1920, when the French railways recommenced the Calais-Méditerranée-Express service, suspended since the start of the war in 1914. At Calais, the train picked up passengers arriving from Britain, and carried them in luxury across France, via Paris, to Nice. In 1922, with new steel carriages and a streamlined image, they relaunched the service as Le Train Bleu—The Blue Train.

Cole Porter had rented a villa near Antibes. The Murphys visited him, and fell in love with the emptiness of the area. A nearby beach was so little used that a meter of dry seaweed blanketed the sand. They excavated a corner in which to enjoy the sun, and later bought a house nearby, christening it Villa America.

Travel writer Eric Newby credits the Murphys with transforming the Côte d’Azur. “Without realizing it,” he wrote, “they had invented a new way of life and the clothes to go with it. Shorts made of white duck, horizontally-striped matelots’ jerseys and white work caps bought from sailors’ slop shops became a uniform. From now on, the rich, and ultimately everyone else in the northern hemisphere, wanted unlimited sun, the sea, sandy beaches or rocks to dive into it from, and the opportunity to eat al fresco.” Shortly after, Coco Chanel landed at Antibes from the yacht of her lover the Duke of Westminister, and fashionable Parisians began to imitate her casual clothing and golden tan.

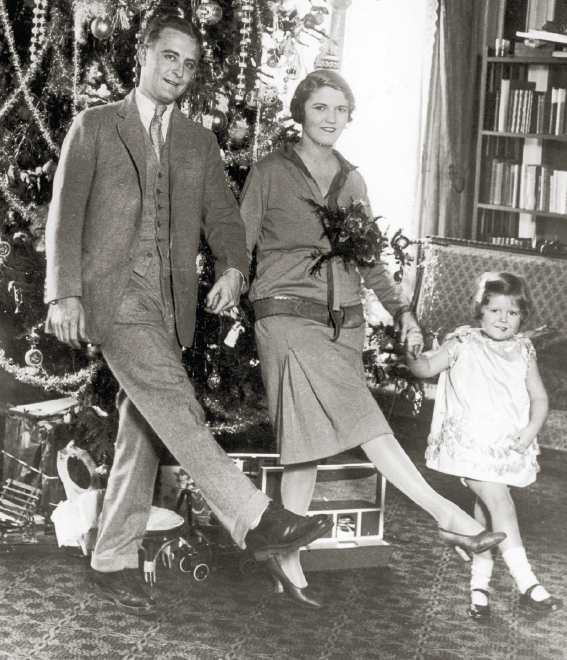

Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald had already discovered the Riviera and rented various houses there, but from May 1926 they became part of a revolving guest list at Villa America that included Pablo Picasso, Man Ray, Cole Porter, John Dos Passos, Dorothy Parker and Jean Cocteau. Intimates recognized tensions within the Murphy marriage and in particular what art critic Alexandra Anderson-Spivy calls Gerald’s “narcissistic sense of inner emptiness and his bisexual impulses.” To Fitzgerald, life at Villa America seemed ideal material for a book, and he began work on what became Tender is the Night.

Inevitably, the focus of the book widened and the vision of the characters evolved. What had begun as a portrait of the Murphys became increasingly a fictional autobiography. In the novel, Nicole Diver goes insane, as did Zelda, and, like Scott, Dick Diver indulges in a number of affairs. “The book,” Fitzgerald said in a letter to the Murphys, “was inspired by Sara and you, and the way I feel about you both and the way you live, and the last part of it is Zelda and me because you and Sara are the same people as Zelda and me.” The Murphys strenuously disagreed. In 1962, Sara Murphy said “I didn’t like the book when I read it, and I liked it even less on rereading. I reject categorically any resemblance to us or to anyone we knew at any time.”

By the time Tender is the Night was published, life for the Murphys had deteriorated. Within a few years, both their young sons died. With the stock market crash of 1929, Murphy was forced to return to the U.S. and take over management of Mark Cross, which he ran with great reluctance for the rest of his life. He never painted again, and allowed many of his existing canvases to become lost through neglect. His suffering prompted his friend, the poet Archibald MacLeish, to write JB, a modern retelling of the story of Job.

His last painting, Wasp and Pear, deceptively tranquil, recalls some brightly colored posters of flowers, fruit and insects he had seen during military training. It shows a smooth green pear in conjunction with a predatory wasp, dull-eyed and malevolent. Is it a metaphor for soft, sweet France at the mercy of foreigners? Or of plump, naive Americans about to suffer the sting of European cynicism? We are left to decide for ourselves. However, in a letter to MacLeish, Murphy wrote of their days at Villa America “What an age of innocence it was, and how beautiful and free!” As his justification for a life spent in the pursuit of pleasure, he proposed an old Spanish proverb: “Living well is the best revenge.”

Tender is the Night, though acknowledged, even by its author, as flawed, remains the most vivid evocation of Villa America and the Murphys. Otherwise, modern France has few reminders of them. All Gerald’s seven surviving paintings are in the United States. A few memoirs and biographies evoke the Riviera of their time and a community which, in the words of humorist and then-newspaperman James Thurber, “was full of knaves and rascals, adventurers and imposters, pochards and indiscrets, whose ingenious exploits, sometimes in full masquerade costume, sometimes in the nude, were easy and pleasant to record.”

Of that Côte d’Azur, the best reminder in Paris is found at the Gare de Lyon railway station (12th). To mark l’Exposition Universelle of 1900, the Compagnie Paris-Lyon-Méditerranée (PLM) inaugurated a 500-seat restaurant at the station from which trains to the south departed. It was here that the Fitzgeralds and Murphys, Picasso, Chanel, Cocteau, Stravinsky and Diaghilev gathered to share a bottle of Bollinger while they waited to entrain for south. In 1963, the restaurant was renamed, in honor of the PLM’s best-known service, Le Train Bleu. André Malraux declared it a historical monument in 1972. Forty-one exuberant murals and ceiling paintings celebrate the sun-drenched destinations served by the PLM’s trains, and a décor of brass, leather and varnished mahogany evokes the age of luxury rail travel, now returning to France, courtesy of its speedy, silent and comfortable high-speed trains.