The Lake

Henry David Thoreau says, “A lake is the landscape’s most beautiful and expressive feature. It is earth’s eye; looking into which the beholder measures the depth of his own nature.”

There is something about the water that brings us to the shore, so that we can sit and look out over it. The lake is our cottage view-scape, ever-changing, its sound and texture altering constantly. It is mesmerizing, bewitching, and expressive, and one of the constants that makes our cottage experience so special.

Whether we have a huge lakeside home or a humble cabin, it is the desire to live on the water that draws us. The lake is everything. The lake is why we are here. We rise in the morning and look out over the water. We take our coffee to the dock. Perhaps we sit reading, but we are constantly distracted by the water.

The lake is full of life. Our loons and mergansers make it their home. We admire their freedom as they dive and slice through the water. They rise on the lake surface, flex their wings, and then dance across the water, windmill their wings, and shoot up spray like a skier. In the evening, the fish jump, and minnows hide in the dock pilings. The kids catch frogs and crayfish, and try to avoid the leeches that skulk in the silty shallows. They are fascinated by the water spiders, which dart about in apparent confusion. In the night we listen to the waves breaking on shore, hear the loon’s shrill call, and the slap of the beaver tail.

Throughout the day the lake is the focal point of our summer fun and recreation. We love to swim and play in the water. There is constant laughter, splashing, diving, and jumping. We take the canoe out and explore, paddling along the shore. We ski, sail, or wake-board the lake’s surface. We fish its depths, and snorkel and dive to find its hidden treasures. The lake’s waters are beautifully refreshing on a hot summer’s day.

As it gives us much joy, the water also demands our respect. The lake, though so full of life, can also bring death. On more than one occasion our lake has taken someone, a boating accident, or a disaster on its winter ice. It humbles us. The lake sometimes flexes its muscles and shows its harsh side. Then, it turns around to let us know it can be soft and gentle. It ravages our docks, and then sings us to sleep. The lake waters can whip themselves into a fury, waves crash onto the rocky shore, shooting plumes of spray skyward in an angry and fearsome display. The lake screams and hollers, and then suddenly it is calm, and the ripples lap the pebble beach, whispering the lake’s secrets, so quietly we have trouble hearing.

My mother loves living on the water. When, as a young family, we lived for a year on the prairies, she hated the open, dry, dusty, grassy expanse of land. The lakes there, she remembers, were no more than reedy ponds. She wanted to return to lake country. When I lived out west as a young man, in the spectacular and rugged Rocky Mountains, she would visit and feel trapped, closed in, and claustrophobic. The awe-inspiring peaks were not her favourite vista — she preferred looking out over the water. She loves living at the water’s edge.

I guess cottagers are like that. As island cottagers, our lake surrounds us and contains us. We can never quite escape from its presence. Its calm waters are a mirror to the surroundings, and a window to the soul.

All for a Blueberry Pie

My wife and mother-in-law wanted to go blueberry picking this morning, so I dropped them off at a neighbouring island about a mile distant from ours, one that always boasts a bumper berry crop. Their plan was to pick enough berries in the cooler morning hours for a couple of pies, and then to shut it down before the midday heat. I set them ashore with some plastic buckets, and then, with a wave and a promise to pick them up in an hour, I boated home.

It is that time of year when the wild blueberries are everywhere and ripe for the picking. We have some bushes growing on our island, enough for a handful for the morning cereal or pancakes, but not enough for a full pie. Unfortunately with kids and dogs running around the place, most of the blueberries are lost.

My wife tried to convince me to join her, but I know I will accomplish more here working on the cabin, where a list of summer chores needs to be tackled. Besides, I find picking berries to be a mundane and tedious task. My mind tends to wander, and when I have barely picked enough to cover the bottom of a small coffee cup, while my wife has filled a large juice jug, I tend to get in trouble. “No, dear, I will stay, watch the kids, and your dad and I can tackle the porch roof.”

After another cup of morning coffee to fully wake us and prepare us for our chores, my father-in-law and I set to work on the porch, pulling off some of the roof joists that are rotting and replacing them with new timber. We hammer in new supports, and fix up places where the roof has started to sag. We take a late morning break and admire our work.

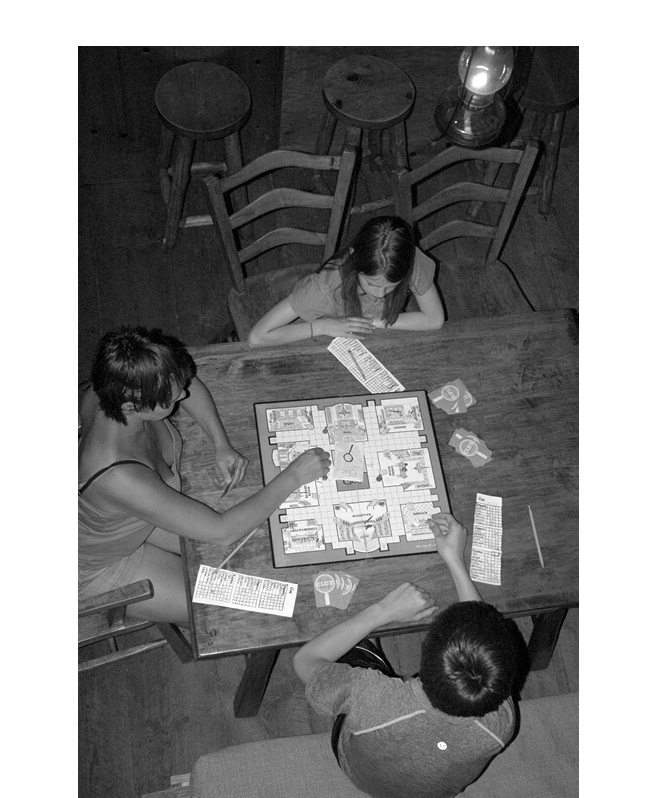

As well as being productive, it has seemed a very quiet and peaceful morning. Only the distant screeching of some noisy ravens interrupts the stillness. The kids spend some time playing in the water out front where we can keep an eye on them, jumping off the dock and wrestling and throwing each other off the swim raft. Now they have retired to the cottage and are absorbed in a board game.

We carry on with some other chores. I buck up some wood and split it for the woodbox. I hear the wailing of the far-off birds again, angry gulls perhaps; not ravens surely. I cut and peel a tall, slim pine for use as a new flagpole, to replace the old one damaged in the wind. My father-in-law attaches the hardware, rope, and pulley system and we raise the flag. We grab a couple of cold beers from the fridge in the boathouse and salute the Maple Leaf.

The midday sun is getting hot, so I jump into the lake to cool down and to wash away the sawdust. My compatriot fits in his custom-made ear plugs to do the same. He was a navy diver in his younger days, and damaged his one eardrum. The fancy ear pieces allow him to swim. His earplugs also drown out all sound, so I’m not surprised that, as we sit there drying in the sun, it is only I who hears again that distant wailing of the water birds, and it is only I who thinks that the squeals, squawks, and general screeching of said birds sound a lot like they are shrilly crying our names. I shake it off.

It is only when my absent-minded relation states, “It must be getting late. I’m kind of hungry — I wonder what the ladies have planned for lunch,” that we both look at each other and run for the boat.

Now, the end of this story is somewhat predictable. My father-in-law and I are not fully able to enjoy the fresh wild blueberry pie at supper, and I’m thinking of investing in those custom-made earplugs, the same kind that my wife’s father surreptitiously slips into his ears as we pull into Blueberry Island to retrieve the angry berry pickers.

Cottage Prepping

It always seems in early spring that my wife and I get restless. It is the drawback of the island cottage — there is a period of forced absence. We have to wait until the lake ice melts away before we can open up the place. It is during that forbidden time, usually from late March to mid-April, when the ice becomes unsafe. We can only stare from the mainland out to the island.

We will usually take advantage of this sabbatical by doing some cottage prepping at the Spring Cottage Life Show, to see all that is new and fanciful for cottage living. This year, however, we decided to do something a little different, so we trekked down to the big city a weekend earlier and took in the Wine and Cheese Show. It represented a virtual round-the-world taste test to find that ultimate wine to sip on the dock in the late afternoon after a busy, fun, and productive cottage day, or that full-bodied red to compliment the thick steaks that I would have cooking on the barbecue.

We started at the show wandering up and down each aisle, savouring the best vintages the world had to offer. While some of those standing around us would swish around the tastings in their mouths, gurgle it like mouthwash, and then, and what’s the sense in this, spit it out into some stainless steel spittoon, we would take a sip, close our eyes, and imagine ourselves laid out in loungers on the cottage deck with the sun warming our faces, or sitting around the big pine kitchen table enjoying a fine meal. While others would talk about their wine exhibiting the beautiful sweet nose of spring flowers and a taste of such richness that it massages the palate with the flavours of chocolate, gooseberries, and leather oxfords, we would ask which offerings might best repel blackflies. There is nothing worse than swallowing a drowned insect in one’s robust merlot.

We sipped Italian Chianti and decided it would complement a cottage comfort meal of spaghetti and meatballs. We tasted an Argentinian Malbec and muttered, “mmm — steaks on the barbecue.” We swirled around a Pinot Noir from New Zealand, a Californian Cabernet, and something unpronounceable from Great Wines of China. China? — really. It wasn’t bad ... we decided it would go nicely with Chinese. The great wine regions of Ontario were well represented, Strewn from Niagara and Crew from Erie — great for the cottage we decided.

We sipped our way through most of the afternoon, and for most of the day our romantic city escape and cottage prepping plan seemed well founded. Then, two things happened. First, we started to realize the value of using the spittoons. No matter, we had wisely booked into a local hotel and had taken a shuttle to the show. Still, the wonderful wines had probably clouded my judgement a bit and had made my wife less tolerant. Wandering down one of the last aisles I came across a wine tasting seminar being advertised. “Get Naked With Wines,” it was called. I stared in at the young, nubile speaker and immediately signed us up.

When the pretty vintner swirled around wine in her glass and said things like “you have to check the legs, the lighter the wine the faster they run, the fuller, the slower,” or “a slight hint of melons and the essence of candy,” or “this is likely a little more body than you’re used to,” I thought she was speaking directly to me. Worse than that, my darling spouse thought that I was thinking that she was speaking directly to me.

Cottage prepping! We have some newly discovered wines we want to savour dockside. I can swirl a rich, robust wine around in my glass, look over at my wife and proclaim, “beautiful legs.” Perhaps that will get me back in the good books. Or, maybe, such tasting theatrics are redundant; a good bottle of red sipped at our favourite place on earth will suffice.

The Chair

I have my favourite chair at the cottage. It sits on the western side of our porch. I think it was my father’s favourite before me. Sometimes I have to kick one of my kids out of it so I can sit down. Sometimes I give it up quietly and without complaint to a guest. I hover around, feeding them light beer until they have to excuse themselves, then I sit and refuse to budge for the rest of their visit.

My favoured seat is not the Muskoka chair, though we do have a collection of these on our dock. I will sit there for a morning coffee, for lunch, or when we gather for a late afternoon drink. They are comfortable enough. These chairs have become representative of cottage country, of life at the lake, as popular a cottage icon as the loon and moose. I have felt, perhaps, that the Muskoka chair has become an overused brand.

Still, I can’t say I’m above its exploitation; I used one on the front cover of my recent Cottage Daze book. The front cover photo of an empty red chair at the end of the dock seemed to represent an invitation to sit down, look out on the lake, and ruminate about cottage life — exactly what I wanted to convey. That is also what we often like to do at the cottage. Sure, we like a high level of energetic cottage activity as well, but at other times we simply love to sit and relax. This place is our escape, after all.

Now, it is not my intention here to get into the great Muskoka chair versus Adirondack chair debate. Yes, this now iconic chair was originally constructed in 1903 by a man named Thomas Lee, who was simply looking to have better seating for his Adirondack Mountain cottage. The simple design featuring eleven pieces of wood cut from a single board, with its slanted back and low-level seat, quickly became a preferred summer chair in many places.

Sensibly enough, as Muskokan cottagers, we stole the plans and made the chair our own. Our Muskoka chair is truly a statement in cottage style and one of the traditional accoutrements of the cottage experience. There are all sorts of adaptations, in vibrant colours, constructed from traditional hemlock, to cedar, teak, resin, engineered woods, and recycled plastics.

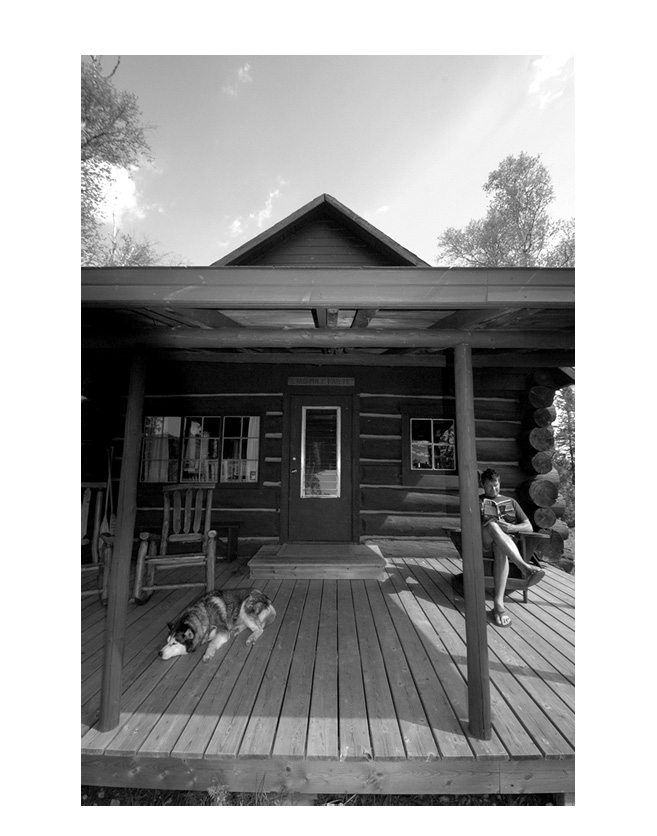

On our cottage porch we have a couple of rough-hewn log rocking chairs that were introduced to the place in 1974. They are fine chairs if you like to move while you talk, or move when someone else is gabbing. It is the third chair on the porch that is my personal throne, a big, roomy, high-backed chair. It has a straight back built out of one piece of solid pine and wide, level arm rests perfect for setting your book on or for holding a cold drink on a hot afternoon. The chair came with the cottage, and in its thirty-eight years. I’ve always remembered it being on the same side of the porch. Switch its position with the rockers and things just wouldn’t be right. It is well-weathered and comfortable, sporting the gouges, scratches, and marks from years of use.

Originally it was known as the Wiser’s Club chair, simply because it was part of a set that was constructed for a “Gentleman’s Club” of sorts. In the 1960s, cottagers would gather weekly at a lakeside lodge, the only place on the lake that had a record player, and then gentlemen got into the routine of bringing along a bottle of Wiser’s to enjoy. I’m told a camp boy designed and built the chairs. Over time, almost all have disappeared — we ended up with perhaps the last of this unique design. Now, not a drinker of rye, I prefer to refer to the Wiser’s chair simply as “my” chair, the perfect fit, a place I love to seat myself to look out on the lake and to contemplate how lucky I am to be here.

Tools of the Trade

I remember standing on the rickety wooden porch and staring through the big picture window, my hands cupped on the glass to shade the reflection. What I saw was a fascinating treasure chest — a museum-like collection of the macabre. On the log walls of the big, open one-room interior was hung a variety of metal tools — instruments of torture, an array of Inquisition-like implements that I would be able to put to proper use on my younger sister. There were chains and hooks and some kind of shackles for securing the prisoner. There was a double-sided broad axe, obviously for finishing the job when the prisoner finally relented, confessed, and mercy was bestowed. There was a double-handled cross-cut saw, in case mercy was not the way and I was forced to saw my sibling in two.

I gawked through the windowpane, fascinated by what I saw. This was August of 1974, and my parents had just put an offer in on this island cottage. They had gone out in a canoe one afternoon from our campsite on the mainland with no intention or expectation. They returned excited by a treasure they had stumbled upon. The prize was a quaint and charming log cabin on a three-acre island. It was meant to be. We kids had paddled over from our lakeside camp spot to see the place. “Look at the beautiful wood furniture inside,” my parents had told us. “It looks so cosy and comfortable — and, there is a loft! A ladder leads up to a sleeping loft at the back.”

I hadn’t immediately noticed the fine furnishings, the bedrooms, the wood stove, or the polished beauty of the place. It was the instruments of torture that caught my young eye. In truth, the wall decorations were actually all the logging implements used to build the log cabin back in 1928. While this didn’t impress me at the time (in fact it kind of thwarted my sadistic intentions), I would later have to admit that the tools were conversation pieces of interest to most mature and well-adjusted adults. And I’m sure they still could be put to use in some fiendish way if the need arose.

On the walls of the sitting room, hung by wooden pegs, were a single pole axe, a broad axe, a double-bitted broad axe, and an adze. There was a felling saw, a double-handled cross-cut saw, and an antique buck/bow two-man saw. There was a long-handled peavey, to pick and clasp and turn the downed timber, and a block and tackle, heavy gauge chain, lug hooks, timber carriers, swamp hooks, grab hooks, and grapple hooks for manoeuvring and moving the logs on the ground.

There was a big set of skidding tongs that I felt should be moved to the barbecue for handling huge steaks, and a heavy maul perfect for tenderizing them. Sitting on a bookshelf like a huge paperweight was a log stamp, with the number twenty-two on it, the same number that is imprinted on the end of each log used in the cottage’s construction.

It is like a well-organized museum display, a virtual construction history of our cottage. Every instrument needed, from the antique axes and cross-cut saws used for felling the trees to the broad axes and adzes used for the squaring of the timber. Once down, the logs were stamped and then floated to the island, where the block and tackle, chains, hooks, grapples, tongs, and peavey were used to manhandle each enormous timber into place.

We now use a lot of the heavy steel hooks and chain to hang oil lamps from the ceilings. We used some logging chain to suspend a solid piece of timber over the kitchen island, a water-polished piece of wood that came from the old dam at the northeast end of the lake. On it are hung pots and cast-iron pans. Chain and spikes are also used for a beautiful hanging shelf by the main bedroom.

The collection of logging implements and artifacts has been kept together, and remains displayed on the sitting room wall. The logging tools and the large log construction of the place hearkens back to an earlier time, when the old-growth pine grew stout and tall and logging was the economic background of our lake country. The building of our log cabin was beautiful work, and hanging the implements used on the wall paid homage to the cottage’s creation.

Muskoka Time

I consider myself one of those lucky people. Not only do I have a beautiful cottage retreat, a nice little hideaway on a little island in the middle of a lake, I also have a home in Muskoka and live here year-round. What a great place to raise a family!

I had my first lesson on the abstract concept of “Muskoka Time” shortly after we moved here permanently in the summer of 2005. To procure home insurance, our agent insisted that we have our chimney cleaned by a professional. To that end, I took out the directory and looked under chimney sweeps, called, and made an appointment for one Tuesday morning at ten.

I spent that Tuesday peering out at our empty laneway, watching intently for any approaching car or truck, expecting, I suppose, some soot-covered version of Dick Van Dyke to walk down carrying his big brush. Nobody came. Wednesday it was more of the same. I tried phoning. His secretary/wife could only tell me that I was indeed on the list and he should arrive at any time. Any further information was classified as Top Secret. I waited another day. On the Thursday I had work and chores to do, and tried to slip out quickly in the morning. I arrived back home to find the tardy sweeper standing beside his pickup tapping his foot.

“I was supposed to clean a chimney here,” he complained. “But I get here, and nobody has the decency to be home. I’m a busy man.”

Shocked as I was by his demeanour, I tried to patiently explain that he was supposed to be here Tuesday, a time when I sat home waiting. With a slight know-all smile, the kind fellow informed me that if I wanted to live here, I might as well get used to Muskoka Time.

Lessons followed lessons, and I learned about Muskoka Time from the best — contractors, electricians, repair persons, waiters, and waitresses. I was shocked when my parents broke their ceramic glass stovetop at their Muskoka River cottage. It happened when a pot came tumbling out of an overhead cupboard and smashed the surface beyond use. They phoned for service and were told a new top would take about a week. This was on a fine spring day in early June. They spent the summer cooking on their outside barbecue. When I expressed anger over the service, they calmly put it down to living in Muskoka. Their patience only began to wane as the crisp days of autumn arrived, tugging winter close behind. Finally the stove was repaired just ahead of winter, allowing them to store the barbecue. I would have been outraged; my mother called the repair person a nice young man — about my age — with kids. It was as if we were living somewhere on Baffin Island, but really it was just Muskoka Time.

I dabbled in Muskoka Time myself on a few occasions, purposely showing up five minutes late for a meeting or three minutes late for an appointment. Still, I was ashamed and embarrassed, and often felt I should apologize for my lack of punctuality, and I would have if anybody else had been there yet to listen. I guess I am simply slow to adapt to the concept. Not so my children, who display a definite knack for Muskoka Time — especially when prodded to clean their room, come in for dinner, or get up in the morning and out to the school bus.

The fairer sex, too, seems to adapt more readily. When my wife leaves me at home with the challenge of minding the fort and surviving the kids, promising to return from her shopping by noon, she often reappears just as the sun sinks below the trees to the west. When she goes out for a dinner with business associates saying she will see me in an hour, she will return in the wee hours of the morning. With a sweet smile she explains it all with Muskoka Time.

Today is a beautiful late summer’s day. The morning sky is a brilliant blue and the rising sun feels pleasant on my face and arms. I sit comfortably on the deck, enjoying a morning coffee. The kids are off to school and it is wonderfully peaceful. My courteous wife, in cleanup mode, drops a to-do list in my lap. She is a firm believer that the less thinking I have to do about what needs to be done, the more work I will accomplish in the end.

I eye the list, I survey my kingdom and see all that needs attention. Then something glorious happens, something wonderful, something best put down to the warm enchantment of a beautiful day in cottage country. I feel suddenly enlightened and overwhelmed by the spirit of Muskoka. I pocket my list and, smiling, I sink back in my chair and close my eyes. I will get to these household chores, all in my own, good Muskoka Time.

Sounds of the Cottage

In a recent poll listing the top ten things people love about life at the cottage, surprisingly the slamming of the cottage screen door came in at number one. Obviously the sound of the tight spring squeaking and stretching, and then pulling the door shut with a slam had imprinted itself in the psyche of a good many cottage dwellers.

Unfortunately, we do not have a screen door on our log cottage, much to my wife’s chagrin. I know that my mother had nagged my father to add a screen door for many years, but it never happened. I’m not sure they were necessarily after the sound, but rather the fresh breeze that would circulate in the cabin through the open screen. What I do know is that if I can somehow engineer that screen door into the cabin’s design, I will be treated like a conquering hero (and I will eliminate the sound of whining).

We always long to escape to what we like to call “the peace and quiet” of our cottage. The truth, however, is that there are many sounds that fill our cottage environment — the sounds of water, weather, and wildlife, all sensory touchstones for cottage memories.

No one who has heard the call of the loon, the mournful wails and crazy laughter that can haunt a still, dark summer’s night, will ever forget it or fail to associate it with the cottage on the lake. It is because of this distinct sound that the loon has become a symbol of wilderness and a vital component of it. I am often sitting by the campfire entranced, light from the flames dancing across the white rock, when the silence of the night is pierced by the loon’s cry, the wail of the insane. It is a call that is impossible to describe.

Other sounds interrupt the silence of the twilight hours, and seem more acute, rich, and distinct when offered in the dark of night over the still, black water. There is the hiss and crackle of the fire, and the song and chatter of people. Often my dad has pulled out his harmonica to entertain. I remember during a canoe trip on the distant Bowron Lakes chain of British Columbia, a fellow camper pulled out his harmonica and started playing. I immediately thought of our cottage and longed to be there.

In the evening we hear the peeping of the frogs; a charming orchestra. There is the lapping of the water against the boat at the dock. When we have settled into bed for the night we hear the waves gently curling under the boathouse floor, more soothing than a bedtime lullaby.

Unfortunately there are sounds we could do without, such as the buzz of the mosquito. You have just extinguished the lamp and snuggled into the down comforter, eyes fluttering shut, drifting off so peacefully — when you hear the faint buzz. It is at a distance, but gaining in volume. Your eyes open wide, the mosquito hovers just off your ear. You wave a hand at it. It is silent and you know it has landed, so you shake like a dog. Your wife wakes to find you with a flashlight on, jumping up and down on the mattress grabbing at the air in some ridiculous demonstration of disco Tai Chi.

In the early hours of dawn, you hear the dogs frolicking and running, and the chitter of the squirrel reprimanding their intrusion. The songbirds welcome a new day. A song sparrow sings a beautiful melody from a tree outside the boathouse bunkie. How long do song sparrows live? My mother remembers the sparrow offering his sweet music from the same tree back in 1974. Perhaps it is the offspring of the original singer, in a tree grown much higher now.

There is the sound of the bacon frying on the morning fire and the hushed speaking tones of early risers with their coffee on the dock. There is the splash from an early morning dip, the sound of the motorboat belching to life, and then the slice of the water ski through the calm lake. There is always the joyful sound of children’s laughter while swimming, running in the forest, or playing in the cabin.

In mid-morning there comes the sound of the wind, the waves crashing on the shore, and then the rain pelting off the cabin roof. The flag flaps, thunder roars, and lightning lights the sky.

There are so many sounds that make up the cottage experience; beautiful, relaxing, bewitching noise. Sounds we have learned to love, amongst the peace and the quiet.

Cottage Top Ten

As top-ten lists seem to be in fashion, and since I long to be a fashionable guy, I decided to put together my own top ten of what the summer cottage means to me. In the end, however, so unoriginal and uninspired was my list, I decided to approach the experts, my children, to get their perspective on our summer place on the lake.

So what began as a ten-point list by me transformed itself into a family exercise, as I implored my wife and our four kids to write down the ten things they love most about the cottage. It was a great time of the year to ask, with just a month of school remaining and the youngsters pining for summer, longing to spend those long weeks at the cottage without a care in the world.

My own favourite touchstones for cottage living reads more like a series of mood-driven advertisements in Cottage Life magazine: coffee or tea on the dock in the early morning while watching the mist rise from the lake; sitting in the Muskoka chair in the dark of night looking up at the stars, sometimes being fortunate enough to see a display of the northern lights; watching a thunderstorm come across the lake; sitting, reading in the cabin in the evening under the warm glow of the oil lanterns; cocktail hour lakeside; and watching the dogs run all day before crashing into a deep sleep, curled up on the porch.

My wife’s list was also made up of relaxing moments, the cottage for her being a place to escape the stress of work, to recharge, and to distance herself from responsibilities. She mentions sitting out at the point surrounded by the fall colours, or in the antique bathtub filled with water heated on the cookstove, soaking, looking over the lake, with a glass of wine in hand. The hardest decisions while at the cottage are whether to partake of a beer or cider with lunch, what book to read, and whether to lie and sunbathe on one’s back or front.

There is much more energy involved with the children’s lists. They mention water-skiing, knee-boarding and tubing, snorkelling and swimming, and fishing and canoeing. They cherish the time spent with their siblings, friends, and cousins, running through the forest, playing tag, hide-and-seek, or manhunt.

Also, interestingly enough, there is a common thread that weaves its way through the lists of parents and children alike, and it is rated highly in the top ten of all. That is, the love of shared family time. Now, as a parent I understand our desire to get the children and ourselves away from televisions, telephones, Playstations, computers, and MP3s, but the same sentiment topped the lists of my kids.

Each of our four children mentioned family time: games, bonfires, marshmallow roasts, singalongs, treasure hunts, and ghost stories before bed. Sitting down in the evening after supper and playing a board game with Mom and Dad was their biggest thrill.

How important is that, and how gratifying to know?

I put the top-ten question to Grandpa and Grandma. They also listed the quality time at the cottage with family and grandchildren, and the joy and quiet when everyone leaves and they can enjoy the place alone.

The Bookshelf

I love to read. My day just doesn’t seem complete if I haven’t read at least a couple of chapters of a book. Our cottage comes without electricity, so no television or Internet. This leaves plenty of time to get lost in a good yarn.

I was reading with my son the other night, and it is nice that he is at the age where he enjoys doing most of the reading himself, only letting me take over when his eyes are getting heavy. It was a Hardy Boys book, but not the Hardy Boys as I remember them. When I was a kid I used to sit in the big comfortable armchair on the front porch of the cottage and read the entire series, stories of mystery and adventure. My sister sat in the log rocking chair and read Nancy Drew stories, and then we would argue whether boy detectives or girl sleuths were best.

Now the “All New” Hardy Boys, Frank and Joe, use cellphones and the Internet. They battle gang leaders instead of thugs, and their best buddy, chubby Chet Morton, doesn’t seem to be around, at least in this adventure. Perhaps it is politically incorrect to have a plump, nearsighted friend who loves to eat. Where they used to drive around in jalopies, now they scoot around on sleek motorcycles. The writing has changed as well; it is more upbeat and funky. Frank and Joe themselves are more obnoxious, which of course is “in.” They call each other “pumpkin-head” and “doorknob.” I don’t remember them doing that in the original series — in fact, having brothers myself, I found their fine behaviour towards each other a little weird.

We have a neat collection of books that sit on rustic shelves in the back corner of our log cabin, rough wood planks suspended from the loft by logging chains. There are a number of kid’s books: the Hardy Boys both new and old, Nancy Drew, Harry Potter, A Series of Unfortunate Events, and the Spiderwick Chronicles. There are classics like Treasure Island, Black Beauty, Kidnapped, Who Has Seen the Wind, Tom Sawyer, and The Swiss Family Robinson. Some of the books are more recent, and rotate in and out as people finish reading them. Others have been around for decades, classic novels and timeless journals on the outdoors.

There are the usual volumes on nature, of course. Beside the binoculars sit several books on birds. So when my wife says, “Oh isn’t that a pretty bird on that birch branch,” I can reply with certainty, after hurriedly flipping through the Audubon book of North American birds, “I believe that is a white-breasted nuthatch.”

“Whatever,” she replies, seemingly unimpressed with my vast knowledge, and then under her breath, “And you’re a brown-topped nuthead,” something I can find nowhere in any of the volumes. Then my son, flipping through the bird illustrations to help me out, says, “Are you sure it isn’t a common bushtit, Dad?” to great giggles and laughter.

Annie Dillard is one of my favourite authors. I guided her on a horse trip in the Rockies in the mid-eighties, and she gave me a signed copy of her Pulitzer Prize–winning novel Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. Beautifully written and wonderfully observant — I pull it off the bookshelf often. Other volumes that will sit gathering dust for some years, and then get pulled down for a good afternoon read include the books of H.V. Morton, Gavin Maxwell, James Herriot, and Henry David Thoreau. When needing something light-hearted, I might turn to Gregory Clark, Stuart McLean, or the travel books of Bill Bryson.

Also on the nature shelf are wildflower books, books on the night sky and constellations, animal tracks, mammals, edible plants, and mushrooms, so my wife knows how to poison me if needed. There are books on cottage country walks, lost canoe routes, Algonquin Park, animal husbandry, and books on how to care for cast-iron cookery, which my wife will set out discreetly from time to time. There are many how-to books, of course, Foxfire books that tell you how to dry fish, tan a hide, or build a sweat house, just those things you might think of doing on a lazy cottage afternoon. There are much-used first aid books, cottage repair books, and books on how to deal with teenaged children.

The top shelf is more of a rotating collection of spy, adventure, horror, and mystery novels — Wilbur Smith, Robert Ludlum, John LeCarre, Ken Follet, Stephen King, Jack Higgins, and Peter Robinson. They come and go. Of course there are a few Danielle Steele and Sydney Sheldon romances, the Fifty Shades Trilogy, and several Oprah recommendations — don’t know where they came from. Likely from the same person who thought a girl could solve a mystery as well as those brilliant brothers. What an absurd notion!

The Perfect Day

It was the perfect day at the lake. Sometimes, unexpectedly, those perfect days just arrive. Sometimes you just have to allow yourself to relax to let them happen.

It was to be our last day of a two-week stay. We had enjoyed some sunny days and some rainy days. We had enjoyed some laughs and fun, and done our fair share of hard work along the way. We had completed a number of projects — some that we had been intending to tackle for some time. I crossed them off the lengthy to-do list.

On that, the final day of our vacation, we had pledged to store away the tools, to relax, and to enjoy our time with the kids. My parents had always followed the policy of only working until noon during their cottage days, before forcing themselves to slip into a lazy routine of reading and swimming for the remainder of the day. It was a well-thought strategy.

I woke early in the morning to mist rising off the lake. It swirled and drifted. The rock outcrop to the north looked cut off from shore. My dog stood on the stone island looking out over the peaceful water. Her head tilted as the sound of a loon echoed from the fog. She lifted her nose and let out a brief howl in response.

As the mist lifted, the lake was as calm and still as glass, reflecting the vivid blue sky and the few fluffy clouds like a mirror. The children rose early (well, early for them), with the promise of some excellent water-skiing. We took each of them around in turn, watching as their skis sliced through the flat water sending a plume of spray behind.

My eldest daughter dropped a ski for the first time. She wobbled and fell, but tried again, and proudly skied around the bay. By the end of her turn she was confidently carving in and out of the wake. When the youngsters were finished, the adults all gave it a go, for a brief time becoming children again. Some of the kids went tubing, and then Grandma and Grandpa took a turn. We all laughed as they bounced over the wake and skidded wide-eyed to a stop beside the dock.

We had set up our annual treasure hunt for everyone after lunch, so the adults could relax dockside and watch the children solving puzzles, deciphering riddles, and following clues in their search for hidden treasure.

My wife, her mother, and my sister swam the mile distance from island to shore, a goal they had set for themselves when arriving at the cottage. They had trained by swimming around the island almost daily. My brother-in-law followed them in the boat for safety (I would have never heard the end of it had my mother-in-law sank), and then we brought them back in spite of the relative quiet we had enjoyed for a time. We toasted their success. My sister and I shared memories of the last time we had done this swim, as fit teenagers thirty-some years ago. I would say that this was a much more impressive accomplishment for the ladies on this day. My shoulder was hurting, if you were wondering.

After dinner I got a bonfire burning at the point, and we sang some songs, told some stories, and shared some jokes and riddles. Sometime during the fun, the sun had disappeared in the west. The lake was dark. Only a few cottage lights could be seen on the distant mainland. With no lights, clouds, or moon, the display of stars was amazing.

Like tumbled bowling pins, we lay out on our backs on the rocky knoll, helter-skelter, staring up at the brilliant canopy of stars. My son used me for a pillow, my daughters snuggled in by my side. My eldest showed off her knowledge of the constellations, saying that she had learned them in school that past year — it made me happy to know she had learned something.

We watched falling stars and satellites drifting past, and lost ourselves in the Milky Way. I asked my kids if, after they had become professional hockey stars, glamorous celebrities, or skilled physicians, they would still lie out on this rock with their old dad looking up at the stars. They all said they would — this was their favourite place. No matter where their life might take them, they vowed always to return. I believed them.

And so ended my perfect cottage day.

A Taste of the Highlands

We have the wood fire roaring in the stove, taking the chill out of the cottage. My wife sits in a rocker reading, while the kids play a game on the pine table. Outside, horizontal rain pellets buffet the cabin. I sit comfortably in my favourite wooden armchair on the sheltered porch, just far enough back to stay dry, a pre-dinner dram of single malt in hand. Low clouds hang over the lake and a misty fog twirls over the turbulent surface.

My ears suddenly perk up. Over the sound of the squall, I hear a distant bagpipe from the mainland echoing over the water. In this weather, it is an appropriate and beautiful sound. I don’t know if it is the sound of the pipes, the inclement weather, or the dulling warmth of the Lagavulin, but I find myself staring out over the lake and imagining myself in Scotland again.

My last visit had taken me to a cottage of a different sort, a distant seaside guest house on the rugged shores of the Shetland Islands. Like our Muskoka, the Shetlands are a wild and wonderful escape — vast, pristine, remote, and mysterious, full of history and nature. Though, where Muskoka is lush, treed and green, the Shetlands are barren. The country there is uncluttered by houses and trees. At first I missed the forest that I love so much back home, but soon the stark barrenness of the Shetland landscape exerts its own fascination. Roads curl through the valleys and follow the rugged shores, past rock homes, stone walls, and neat paddocks.

The cottage where I based myself was called Burrastow House on the West Mainland. After dining on lobster caught in the Sound and served up fresh, I wanted the exercise of a short walk along the rugged, rocky shoreline. I set off on a sheep track that wound its way over the moor and along the ragged coastal cliff-tops. It was sheer beauty, and peaceful, a silence broken only by the stirring of wind, the crash of waves, and the cry of the kittiwakes. Each new bay and craggy outcrop drew me onward, and the late summer light had me walking well into the night.

Like the feelings that are constantly stirred by my island cottage back home, from this barren Shetland landscape one never ceases to pluck strangely rewarding experiences. It sharpens the senses. Peat bog and mist, the smell of the sea and decay, the sounds of the water flowing down the hillsides, rain, wind, and the distant bleating of sheep. Spring quill covered the rocky knolls and thrift grew like lichen on the black rock, colouring it pink. Marsh marigold sprang from the moist soils — yellow flowers following the damp draws. Purplish-black heath spotted orchids grew in the boggy areas. Floating in the white peat water were the white heads of water lilies. The grass, short and tough, was of a greyish-green colour, interspersed with clumps of heather. Puffins, gannets, guillemots, and kittiwakes roosted on the sheer cliffs that rose from the Atlantic in steep-sided splendour. Out to sea I saw whales breeching, and in the bays and inlets otters and grey seals frolicking.

I love wild and rugged country. Though I can’t say I would complain about a hot, sandy beach during the doldrums of our long Muskoka winters, I am not as much a tropical island kind of guy. I prefer being at our cottage on this island, a balsam-scented, three-acre mound of rock, cedar, and pine situated in the middle of a lake in the northern woods. And I love looking out over a lake thrown into chaos by a driving summer storm.

When our whole clan is up to the cottage we fly the Lion Rampant under the Canadian Maple Leaf on the flagpole. Two carved wood Gaelic signs greet visitors to our cottage. Above the front door is Ciad Mile Failte, meaning “A Hundred Thousand Welcomes.” On the central log beam inside is the sign Croich Na Rosach, “Refuge of the Rosses.” We have a certain pride in our Scottish heritage, but a far greater pride in being Canadian and in owning this wonderful bit of Canadiana that is our cottage.

It is surprising what thoughts are stirred up by a summer storm, mist on the water, the distant wail of a bagpipe, and a dram of highland whisky — especially by the malt.

The Ants Go Marching

There is a trail of ants that wander across the walking path that leads to swim rock. They march along with a purpose, organized and in single file. They skirt small stones and tree roots that must seem like mountains and canyons to them. One meandering line treks westward, while a returning column heads east. They pass each other on the right.

Their destination is a big old pine tree, twisted and gnarled and oozing sap. The ants climb the tree, gather some of the sweet sap, and then diligently march off homeward to their anthill constructed out back of the tool shed.

Each and every day, once the sun has sufficiently warmed the earth, the queue of ants begins its daily routine: marching, climbing, mining, and then returning with their booty. Then, presumably, they are off again. I do not know how many trips they make in a day since I don’t know how to tell them apart, how to paint a number on their back, tie a ribbon around an antennae, fix them with a radio collar, or tag an ear.

I saw a program once about ants that stated that the column of ants moves at the speed of the slowest walker. There is no passing, no impatience, no butting in line. They move on with a precision and a politeness not readily apparent in cottagers making the drive to their summer homes.

If an ant from a neighbouring colony somehow gets confused and joins this line, they must abide by the rules. If he passes or butts in front of a fellow worker, the other ants forget their task for a brief moment. They move in and rough him up. “No passing lanes here,” they tell him. “No broken yellow line or four-lane highways.” Taught his lesson, the foreigner acquiesces, and the procession is allowed to continue. This is the only road rage exhibited. Other than that, the ants move quickly and efficiently along.

There are no road signs or distances to passing lanes. The ants do not need the same inane instructions we are burdened with. There are no billboards stating “Large Vehicles Need More Room,” “Big or Small, Share the Road,” or “If You Can’t See, Don’t Pass.” (I’m of the mind that if you can’t see, you shouldn’t really even be driving.)

One warm summer afternoon, after making the stressful journey to the cottage, I am lying out relaxed in the hammock, just happy to be here. In my mind are thoughts of road signs, crazy drivers, passing lanes, and ants. I drift off, and imagine that I’m a member of the hymenopterous species, marching along with my burden of sap neatly tucked under my arm. I’m walking close to the slow-moving ant in front of me, riding his butt, waiting for a passing lane. I know that once I wind through the long grass that hedges the trail, our column will break out into a wide dirt pathway, the ideal place to pull ahead. I anticipate that stretch, where I can leave the toddling creature behind and get back up to speed.

Once there, however, I am shocked when the slow-moving insect actually breaks into a run, as do all of the ants in the line. I must run as fast as my six legs can carry me, just to keep up with the pace. Once the passing stretch ends, I find myself again behind the pokey proceeding, trudging slowly along, my anger and rage building. If I had a horn, I would honk it.

There is no need, however, as what amounts to a miracle occurs. Just when I think I will never pass the agonizingly slow insect, one of those gigantic, ugly two-legged creatures appears, walking down the path towards the water. The snail-paced insect ahead reacts too slowly, and a flip-flop flops earthward, carrying our bad driver away on its sole.

Justice is served! It is clear sailing now. Until ... what’s this? A shorter version of the human comes along, in pigtails. I recognize her as my youngest daughter. She sees the procession of ants marching across the path and begins jumping and stomping. Her foot comes towards me! My journey comes to a sudden end, and I awake in the hammock from my dream with a start and a shriek.

Okay, so our drive to the cottage is not so bad after all.

Cottage Fashion

There is another advantage to owning a cottage. I can hang onto my old, worn out, decrepit clothes just a little bit longer. When my well-aged sneakers spring open at the toes so half my foot hangs free, when the sole of a running shoe detaches and flaps along as I walk, like an alligator trying to devour anything in its path, or when the shoes begin smelling like a cat’s litter box or my son’s hockey equipment bag, my darling wife has the audacity to try to toss them out like common garbage. I retrieve them and say, “These will be perfect for the cottage!”

This is also the case with my ripped, faded blue jeans, the paint-stained T-shirt, or sweat-marked cap. They are perfect for our remote summer getaway. The same may be true for my tattered and rotting underwear, but here I draw the line. As much as I want to keep them and get full value in their wear, I can’t help but remember my mother’s stern warning: “Always wear clean underwear lest you get in an accident and end up at the hospital.” So, I allow the old boxers to get tossed with the rubbish. The rest of my vagabond collection I stubbornly hang onto as “cottage wear.”

Cottage fashion is an interesting and very personal thing. While I prefer old, my wife leans towards new. When spring rolls around and that wonderful time approaches when we plan to open up our summer place, my wife flips through the pages of clothing catalogues to see what is in vogue for summertime. A new outfit for each cottage day is a must, for who knows when Brad Pitt or George Clooney might shipwreck on the rocky shoal off our island’s eastern tip and wash up on shore, castaways at our cottage.

There are those cottagers who always have the look of someone who jumped straight from the pages of an outdoor magazine, with their clean and pressed quick-dry shirts and pants, Gore-Tex jackets, cargo shorts, Tilley hats, and shiny leather high-top hikers. Before their trip to the cottage they need to visit their nearest outdoor store, so they can wander down to the dock looking like models from an Explore Magazine photo shoot.

My sister favours the look of a Martha Stewart protege. My younger brother has the tailored look of a movie actor playing the part of a great hunter on safari. My daughters take after their mother, often changing clothes many times a day. My son prefers to wear the same bathing shorts and T-shirt each day of his two-week cottage stay. My parents look like they were scripted to play Hepburn and Fonda’s doubles in On Golden Pond. My Uncle John wears the same fashions that he grew up on in the fifties and sixties — not just the same fashions, mind you, the same clothes.

Then there is me, right out of the pages of Tramp’s Quarterly. I like an old wool fisherman’s knit, and I prefer rubber boots and an oilskin slicker. While recognizing the advances made in outdoor clothing, I favour the traditional. Or, my wife will say, I’m too cheap to buy new clothes. “Please throw those out,” she will plead. “You’ve had them since university, they do not owe you a thing!”

Some cottagers prefer wool, while others favour Lycra. Cotton is comfortable, but no good when it gets wet. Flip-flops and leather sandals are in, dress shoes are not. The kids prefer nothing on their feet, running barefoot all day long.

Above the front door inside our cabin are two flat-top leather brimmed hats that my brother and I wore on all the many canoe trips we enjoyed as kids. There is a Greek fisherman’s cap that I brought back for my dad after I had spent a week in this Mediterranean country as a teenager. My oldest brother felt best in his buckskin jacket, one that he tanned and tailored himself with leather fringe and intricate beadwork. He wore leather moccasins on his feet. He was a modern-day Jeremiah Johnson. The beautiful buckskin hangs from a wooden peg on the cabin wall.

The only one I feel strongly about is the swim short over the Speedo, and boxers over briefs. Although who would argue against the skimpiest bikinis for the ladies — well, certain ladies? Whatever the fashion, the clothes say a lot about the person, and add spice and variety to the cottage visit. And life at the cottage allows me to hang onto my comfortable old clothes at least one season longer.

Summer Reflections

It is hot again today. The sun is warm already, at eight in the morning, and I am drowsy. It warms my arms and face, making it hard to wake up. A swim is the only way.

There is not a breath of air — the lake is a mirror, everything is reflected perfectly. The only things that disturb the glassy surface are the splash and ripples from me jumping into the water and doing a breast stroke to the swim raft. The water is clear down to its rocky depths. I swim stretched out and see my shadow on the lake bottom, amongst the minnows. I see beams of light from the sun shimmering through the water like spotlights.

I climb onto the raft and squint skyward into the blue. Around our front bay, the shoreline trees are reflected so perfectly in the water that you could take a photo and later debate which way is up and which is down. It is another beautiful day; this summer has been full of days like this. We need some rain, this is very true, but right now I am not complaining. The ankle-biters will be out in force today, with no wind to take them away, but now there is only perfection.

My ears perk up as I hear our cottage front door shutting. There is something about the slam of our cabin’s door — something about the sound that is so comforting and so familiar. I can’t describe it in writing, of course, because it is not really a sound, it is a feeling — at least it makes me feel a certain way. Our door at home does nothing for me, it just shuts. I hear the sound now, and hear the voices of our kids. I know that they will be asking to go skiing. There is nothing quite like carving through the lake’s calm, glassy surface on a slalom ski. It is akin to skiing down a mountain on virgin white powder.

I sit up on the raft and see the kids wandering down the path to the dock carrying skis, tow rope, and life jackets. The youngest and smallest amongst them carries nothing, but shouts out instructions about where to put the gear and who will ski first. I shake my head and smile at this. Water drips from my soggy, tangled hair, and from my greying whiskers. I don’t shave at the cottage, so I sport a raggedy beard, silver around the chin and very itchy. My wife once called it my rugged, sexy look, so I keep trying. I’ll shave when I get home.

A dragonfly zigzags through the air, its fragile wings beating a gentle hum, and lands on my knee. When I was a youngster, my mother told me that dragonflies were flying darning needles that would sew my fingers together, my eyes shut, and even my mouth closed. I’m a rational adult now, but still find the tickle of the insect on my leg a little disconcerting. I keep my eye on this little fellow, and my fingers away and splayed apart. Still, I have heard how many mosquitoes a dragonfly will devour in a day, and so I treat this one with the utmost respect, gently shooing it off my knee and towards my very verbose youngest daughter, who is now yelling out at me from the dock. “Fly away, friend,” I whisper. “And if you want a mouth to knit tight….”

No such luck, and my morning instructions reach me on the raft. There is a lake that must be skied, a boat that must be driven. There is no more time for summer reflections. There is work to do. I dive back in and watch my shadow swim to shore.

Cottage Questions

Along with afternoon, evening, and nighttime, early morning is perhaps my favourite time of the day. The kids are still sleeping, so it is a quiet time. Mist rises from the still lake waters, the songbirds sing from the treetops, and water birds drift in and out of our little bay. I take my coffee down to the dock, look out over the beautiful, peaceful world, and ponder the great mysteries of life.

Why do I “ow” and “ouch” as I walk down the stony path with my cup, each little pebble poking into my tender feet — while all day long the children run around barefoot over gravel and rock without even slowing down? Are their feet that much tougher than mine? Is it simply my extra body weight that makes each step more painful? Or am I just getting soft in my old age?

Why, in the daytime, can mosquitoes sneak up and drill into your forehead without a sound, when at night you can hear them coming from a mile away? In the daylight you just feel a little itch and you rub your head, in the process squashing a bloated insect that has been gorging itself on your blood. At nighttime, you hear the buzz of the mosquito coming — coming, coming, forever coming, until finally it is buzzing inside your ear. The nasty little nuisance ruins your sleep, as squishing her becomes your sole life’s focus.

While on the subject of pesky bugs, how can a minuscule insect the size of a blackfly take a lion-size bite out of your neck? In a related question, how can my youngest and smallest child be the loudest?

Why does it always rain on long weekends and why is it always sunny and beautiful on the day you have to leave? If dogs love the cottage so much, why, on your day of departure, are they always under your feet exhibiting a great fear of being left behind? Why does the wind always still when you are sailing back from the far end of the lake? Why does the boat motor stall and refuse to start when I am water-skiing? And why, on the last day of a canoe trip, are the wind and waves always in your face?

Why are there two seats in the outhouse? How can my son wear the same clothes (same bathing suit and T-shirt) each day of our two-week cottage stay? Does he know what shoelaces are for? Why do I love playing old board games at the cottage in the evening with the family, when if someone pulled one out at home, I would be horrified and chock full of excuses?

Can you imagine spending all your time in cities, never seeing the stars?

Why are there different expectations when I say five more minutes because I want to finish the chapter of a book before starting the barbecue than when my wife says the same at home when she is telling me how much longer she will take getting dressed to go out? When my five minutes are up and my wife says “Don’t worry, I’ll do it,” why do I immediately start to worry?

When minnows nibble at our toes when we are swimming around the dock, should we really be skinny dipping in the evenings when we know there are pike in the lake?

And one final question: I remarked in the opening of this story about the melody of songbirds in the early morning, because I was trying to set a charming, tranquil cottage scene. But really, why are the darn birds so noisy at 5:00 a.m., squawking and peeping and making a tremendous racket, and then as soon as you are awake and up, they suddenly fall relatively quiet?

The truth is, they are the reason I am up at such an ungodly hour in the first place, asking myself all these stupid cottage questions. The chirping nuisances have no respect — especially after I was kept awake all night by some silly mosquito buzzing in my ear. Where’s my slingshot? I think I know how I can get rid of some of these annoying pebbles that hurt my feet. Kill two of life’s mysteries with one stone, as they say.

Who’ll Stop the Rain

I am having trouble coping with the fact that the summer is almost over. Well, it is not officially over yet, but, if you are like me and have kids heading back to school after this long weekend, it is all but done. I am not really sure where the summer went, it just seems to have sped past. Perhaps the summer seemed fleeting because the weather was not really that great. It has been a wet summer, on the heels of a snowy winter, and now winter soon will be staring us down again.

Today started out like many others: threatening, grey, and dreary. The heavy sky grew so black that it made midday look like dusk. A morning drizzle matured into a deliberate shower, and then, just after I told everybody it looked to be brightening, the shower intensified into a monsoon. We sit around the cabin playing games and reading, our faces dark as the sky. I decide it is time to write about rain.

Rain — it has been a frequent visitor to cottage country this year. Rain in myriad forms: mist, drizzle, showers, downpours, sheets, and torrents. Rain so persistent that it can dampen your very spirit, especially for those who have worked all year long while dreaming of that two- or three-week cottage stay.

We have seen some sun as well, of course. The sun will pop its head out for a few hours in an afternoon and its warmth and beauty make us immediately forget the wet. We cling to fleeting moments like this during our brief holidays at the lake. Then, the rain returns like an unwanted house guest.

As a general rule, I try to avoid going shopping on rainy days in the summer. On those wet, miserable days the downtown is packed with cottagers happy to do their town things when the sun is not out. So, to avoid the traffic and congested aisles in the grocery store, I stay away from downtown, the shops, food stores, and malls.

Only one problem: during this damp summer my strategy has proven to be flawed. My family is starving to death. My cupboard is as bare as Old Mother Hubbard’s.

“When are you going to buy some food?” my kids whine.

“Why, when the sun comes out, of course,” I reply, and then, to my family’s chagrin, I explain for the umpteenth time my reasons for avoiding town on a wet day. Sometimes children just do not listen. My wife just shakes her head and then sneaks into town for provisions. She’s from Vancouver, so what does she know about rainy days? The rain turns everything green and beautiful. This is good for my hungry children, who are forced to raid the cottage garden, which is flourishing, growing like the Amazon jungle.

I hate to complain about the weather. When others do it I find it tiresome. For some, it is always too hot or too cold. They whine about too much snow or too much rain, and then when the sun pops out for a week or two, it is too dry and the grass is brown. They wish for cooler weather when it is hot and humid, and then when the temperature drops and it is crisp and cool they say, “Well, isn’t this just like Muskoka.”

I tend to find beauty in whatever a day may bring. I like the rain. Raindrops on the roof at night lull me to sleep. I love watching a good thunderstorm roll through. I’m not a sun-worshipper by any means. I don’t mind sitting in the lounger in the sunshine reading a good book, but I find suntanning boring. But still, a little bit of sun and blue sky would be nice. A nice sunny day just allows one to do so much more at the lake. It even makes a cold beverage taste better.

As I finish working on this, another little narrative of great importance, I look out the cottage window and squint into what appears to be bright light. The thing about writing a column is that there is a week’s lead time before it is published. I’ll write a few paragraphs moaning about the rain we are having and send it to the editor by my deadline, and then the sun will come out and we will have a spell of hot, dry weather. Readers will deduce, once again, that I’m off my rocker and will wonder what I’m complaining about. But, when I write about the rain, it will go away, and that is the method to my madness. Write about rain, and then look forward to a sunny September.

A Room with a View

Though the summer seems to have flown by, as always, I did manage to accomplish all the cottage chores that I wanted to, and that, in itself, is very unusual. Perhaps I kept my summer chore list shorter this year. Maybe I kept my expectations more in check — or, more truthfully, kept my darling wife’s expectations more reasonable. Or, and this is what I try to tell my spouse, perhaps I just flat-out work too hard. I don’t think she will buy that, but perhaps my readers will.

Whatever the reason, I got things done. I spent the last weekend of summer replacing our leaky chimney pipe. Actually, I didn’t just replace it, I upgraded it, putting in insulated piping in the hope that we would be getting to the cottage more often in the colder months. I teetered around on the steep pitch of the cottage roof, fitting the chimney together and patching in the shingles while my helpful wife hollered up instructions from below. It was like having my own private talking instruction manual.

The other major project that we tackled this year was the building of a post-and-beam gazebo on the rock knoll that sits high above our swim rock. It is something that I have wanted to do for several years, but have been putting off — I suppose knowing that if I bought the material and started building, there would be no turning back.

My wife convinced me it was time — she has a wonderful way of doing that. So we worked steadily at it during each cottage visit. I cleared the tangle of spruce that had been taking over the rock, sprouting out of a thin layer of soil and moss. We built a level platform, and then added a solid beam structure and gabled roof. Everything just seemed to come together, solid, square, and beautiful. I felt just like that handyman who has all those cottage projects in each issue of Cottage Life. I mean, does the guy really have any opportunity to actually enjoy his place?

Of course, our new gazebo is different things to different people. My children think that it is a neat new place to hide out when playing manhunt. Someone comes after you through the front door and you can vault out the back window. I just hope that they won’t become conditioned to that escape route, as I do plan to put in screens before next year’s bug season. My darling wife thinks it is a comfortable place for her to drink red wine in the evening. My dad will sit there reading during the day, to stay out of the hot sun, while not feeling left out of all the excitement and kid activity on swim rock. My father-in-law sees it as a place to sneak away to for his afternoon nap.

My dogs think it is the best dog house I have ever made for them, a place where they can curl up on a cushioned loveseat overnight, or escape into during a rain shower. All signs indicate that they are taking advantage of the gazebo’s comforts, but their hearing is so acute that, when you try to sneak up to catch them in the place, you find them curled up on the hard rock knoll giving you a doleful expression meant to portray the pure misery they are in. “This is the life you make me lead,” their expression is meant to convey. “You sleep in your comfortable beds, while my mattress is a slab of granite.” When I point out the circular warm imprint in the cushions where they had, until recently, lay curled, and hold up the silver hairs that do not belong to Grandma, the dogs slink away knowing they’ve been busted.

For me, the new space is an excellent writing studio. For much of the year, I send my kids off on the school bus and try to get a morning of peace and quiet in my office. My ideal work setting is at the cottage. The gazebo sits high above the lake and offers splendid views over the water to the northeast, to the contoured treed hills beyond. Here, distractions seem part of the inspiration rather than interruptions. I listen to the sound of the water, the call of the loon, the birdsong, and the laughter of the youngsters, and I write. Today I write about a new gazebo, a sheltered room with a view. And when I’m done writing, I may take advantage of my dog’s new bed, and curl up for an afternoon nap on the cushions.

In the Eye of the Storm

They could have named the tempest Sally or Susan or Silvia or Sophie, much more appropriate for Mother Nature in a rage. Rather, the autumn hurricane is named after my late belligerent brother. How appropriate. Perhaps he was not amused at the way I had treated his remains, dunking them in the deep waters of our lake. Hurricane Sandy … had he come back as a whirling tantrum just to haunt us?

I guess we just like a good adventure. How else could I explain our timing, this year, for closing the cottage? It was the end of October, when the weather can be a little unpredictable at the best of times. However, what faced us this year wasn’t just an early snowfall. No, over the years we have often closed the place while battling an attack from Old Man Winter. This fall we had bettered that, and picked a day in the midst of this super storm. The raging hurricane that had been buffeting the eastern seaboard in full strength had now moved inland, and, although slightly more subdued, was still a fury as it set its sights on cottage country.

My wife and I arrived at the lake in late afternoon. The sky was a leaden grey, filled with whirling black clouds that chased each other around in anger. The gale roared without pause, a tempest vicious and unrelenting. We looked over at our cottage from the mainland landing and wondered why we thought this was a good idea. Our island was just a little over a kilometre offshore, but today it seemed like it was a hundred miles away.

We loaded our two dogs and limited supplies and pushed our boat out into the turbulent water. I had convinced my wife that we would be safe if we snuck over to our island hugging the west shoreline before slipping between the little islands west of ours, before risking the hundred-metre run across a narrow channel. During this brief crossing our runabout was tossed helter-skelter in the wind and chop. I managed to keep the bow facing into the waves, so other than a complete drenching, we made it to our dock upright and safe.

My two huskies gave me a miserable glance as we crossed, ears pinned flat, a look both haggard and forlorn on their expressive faces, a look quite common to their breed when wet. My wife had the same unhappy look, one also not uncommon to wives when soaked to the skin. I turned the boat around at the dock, so that its bow faced the lake, and fastened the bumpers and tied extra lines fast to the cleats. Usually our dock was sheltered in our front bay, but not today — nowhere could one escape the wind.

The waves crashed on shore in a roar, like the beating drums of fury. Foam covered the rocks. We ran our gear up the path to the cottage, bent forward against the squall. We were buffeted by horizontal pellets of rain, pushed back, soundless when we tried to speak to each other. I started a fire, and soon we were dry, cosy, and comfortable, looking out the big window at our lake, a lake more angry now than I could ever remember.

After warming ourselves, we decided we had better get a start on our chores, so ventured out into the storm. The waves swept over our swim rock, so it ceased to exist, and the lake covered the bonfire pit on the point, scrubbing away the black ash from our summer fires. Water was thrown against the door of the bunkie. Ignoring the spray, we struggled about our business with heads down. I rushed in between swells and set up my rickety stepladder, then fought to fasten the shutters on the bunkhouse window while the wind blew the big wooden covers around like sails. It took all of our combined strength to grapple them into place. We had to yell to be heard.

We hustled back to the cottage to warm ourselves, our coats flapping like kites, the wind at our backs blowing us along so we ran without effort. We worked our way through the closing checklist. My wife sent me up to the roof to finish shingling around our new stove pipe. I tied myself off and struggled against the wind. I felt like one of those sailors sent up to the crow’s nest by Captain Bligh during a fierce gale. I hung on for dear life, yelling down instructions to my wife on the measurements needed for the ice and water shield, and then the shingles. I struggled to fit them in place — though sometimes they slipped from my grasp and blew away like kites into the trees. My patient spouse and the two dogs darted off to retrieve them. It was slow going, but we managed to get things done.

And then — as we worried about our return trip across the lake through the ugly waters — the wind seemed to calm. The tantrum was over, or perhaps the test. I smiled and thought of my older brother. He never took the easy way.

A little hardship and a bit of adventure make for good cottage stories. “Remember when you took me up to close the cottage in the middle of Hurricane Sandy,” my wife will reminisce. “What were you thinking?”

The Canoe

There it was, hanging from the rafters at the back of the garage. It was an old wood and canvas canoe. It was a vintage Minto, in fact, built in the same classic design as the Peterborough. I remember the day we picked it up. It was summer, 1973, and we were camping at Killbear Park north of Parry Sound. We rose early and Dad drove my brother and me across to Minden, where Sandy had one of Mae Minto’s canoes waiting for him. I remember when we first saw it. The canoe was beautiful — the wood glowed, and the green painted canvas gleamed. It was my older brother’s first major purchase in life; bought with money he had earned working on a dairy farm at Bar River.

Seeing it hanging at my parents’ Muskoka River home stirs up a lot of emotions and buried feelings. It looks miserable, worn and lonely, and a long way from the water. I know my parents would never want to part with the canoe, which had belonged to their oldest son. I also know that they didn’t quite know what to do with it. I’m sure it stirred up difficult memories for them, of a life lost. Each tear of the canvas, broken rib, and split piece of planking were part of a life, part of who their son had been. With the canoe, he had challenged the wildest of rivers and explored the remotest lakes.

I stroked its worn canvas sides, felt the punkie keel, and ran my eyes over the cracked ribs. I remembered its beauty, and its woeful condition at first made me sad. But were these scars or beauty marks? The canoe was worn and battered because we had made it so. My brother and I had shared many adventures in the old boat, I in the bow and he in the stern. We had pushed the canoe to its limits, and it, in turn, had pushed us to ours.

We tackled nasty whitewater, even though the canoe’s delicate body would not permit mistakes. The canoe moved beautifully, resplendent in style and grace, yet also fearless when we called on it to be so. We crossed angry lakes and pulled hard against heavy waters. The canoe’s elegant shape glided smoothly through the water like a bird through air. So well- balanced was she that with a yolk and tumpline my brother would carry her across an arduous portage with hands free. We slept under it in the night, our heads sheltered by the canoe and our bodies protected in our canvas bedrolls.

We went on family canoe trips, week-long routes that tested our strength and helped forge our character. These trips tested the family, and we passed. From my canoe I watched my sister paddle along in the bow of the Minto, with my brother leading the way. I know he was proud of her during those days, even though he was unlikely to say so. Still, he carried stories of those family trips through his life, and often recounted them to me with fondness.

In 1974, my parents took the canoe out for an afternoon paddle, off to explore some new arm of a lake we were camping on. They rounded some small islands near the western end and saw one with a charming log cabin tucked back in the birches. Off the point they saw a “For Sale” sign fastened to a deadhead sticking from the water. The canoe had shown them what would be our family cottage, the one that I now own, and about which I write.

Yes, this canoe has given us much — and I know it is now time to return the favour. I have resolved to get it back into vintage condition. I tell it so, and then, with one more stroke of the aged canvas, I depart. I make inquiries into the canoe’s restoration. I learn of another female canoe builder who followed in the footsteps of Mae Minto, one with a shop on the edge of the Seguin River. It just seems right that I bring the canoe to her.

I am often haunted by the image of my older brother, paddling his magnificent canoe with his buckskin jacket and leather wide-brimmed hat. He handles the canoe like it is a part of him — man and canoe moving in graceful symmetry. Then, I think of the canoe hanging there, aged by use and now in its state of disrepair. I see the old cedar strip canoe as his abandoned friend, like the hopeful old arthritic dog watching keenly up the drive for the return of his master, so they can set out on one last adventure together.

Unfortunately, I knew he wasn’t coming.