Sous Spectacle Cinema Research Consultation with Bart Testa

On the Viability of an Exploratory Business Expenditure in the Arts

The one thing I’d say about my publications, oddly enough, is they’re not directly related to my teaching. I edited a book on Pasolini for example, though I’ve never taught Pasolini. The rank I hold is senior lecturer, an evolved position. I began as a tutor, then a senior tutor, then a senior lecturer. In a way, these positions were being invented while I was doing basically the same job. These titles all represent “the teaching stream,” which is differentiated from the “professorial stream” or “tenured stream.” I’ve not really been formally evaluated for my research and publications. That’s just as well with me because I put almost all my academic energy into teaching, though I’ve written a fair bit.

I have done a wide range of teaching in film, and for about fifteen years I taught semiotics at Victoria College. Cinema Studies in the 1970s could be charitably described as an emergent field. It didn’t develop the bells and whistles of a fully armed academic institution until the end of the seventies. It was understandable people would have a home discipline where they took their training and then focused on this novel area or added it on to their specialization. And that’s pretty much how we got Cinema Studies going. The prominence of tutors in emergent fields of study, alongside professors who were experimenting outside their home discipline, was a result of this way of testing those fields, and college programs were a vital venue for all that.

Our program and its faculty are somewhat divided. Some of the people are inclined to formal and textual analysis and others are interested in the cultural resonances of films. Most of us examine both, but it is a matter of emphasis. In the most broad, generic way, people are interested in thematics, and people are interested in stylistics. I’ve always been a formalist. And that’s, I think, really suitable for the place where I did most of my teaching—in the first- and second-year courses, teaching the rudiments of film analysis. I want to point out that this is the formal approach in literature by and large. I would assume that students in literature would be well grounded in the formal analysis of poetry, for example.

Cinema Studies, to a large degree, was initially generated out of New Criticism, and its parallels in the study of visual art. My principal influence as a graduate student was P. Adams Sitney, as well as figures like Annette Michelson and William Rothman, a student of philosopher Stanley Cavell. The key figures in the history of film theory—Münsterberg, Arnheim, Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Bazin, Metz, Mitry—theorize cinema on the basis of an idea, its character, and they get at that character largely through formal analysis. So for both reasons of the culture out of which North American film studies came—initially a literary studies culture—and because of the way in which cinema has been theorized from the 1920s until the 1970s, it has been rooted in formal method.

Therefore, Cinema Studies has a multifaceted inheritance from formal analysis and that’s woven into how it exists as serious intellectual discourse. It’s how it announced to the world that it was worthy as an academic discipline in terms of its core methodology. My idea of purgatory would be to sit around with students who had just graduated from high school to get their interpretations of the movies. I can’t think of a bigger waste of time for me or for the students. Instead we work through formal questions. Why? Because their idea of interpretation has been an unholy alliance between what they should think about things in the world, and the treatment of works of art and social texts—social texts that have been pre-digested for their classroom consumption by social workers who call themselves teachers. That’s the drift in high school education, insulting as that might sound.

There are all kinds of reasons for that. And I really don’t care about them. I only resist them. So there were two reasons, right? Academic respectability: if we’re going to do the academic study of cinema, let’s do it right. And secondly, it was the only way to take students out of lazy interpretive habits of mind—and take ourselves out of the corresponding lazy understanding that students are already wise. Sorry, I don’t think so. I don’t think of myself as wise; why would I think of them as wise? What I did think, though, is that if we worked hard at developing a methodology, people would have a richer basis on which to engage in interpretation, which is inevitable and desirable.

The end goal is, in fact, the interpretation of films. Formal analysis is a means to an end. But the end should be postponed for a time. The idea that works of any subtlety or interest are actually subtle and interesting because they say the right things about the world and people in it seems to me immensely naïve and an unproductive way of thinking about it. When I began teaching we had an Athena Analyzer, which is a sixteen-millimetre film projector that would stop frame, go back and go forward to get close-shot analysis, and it became the basis of my teaching. It was also the basis of my graduate experience at New York University. Going through Eisenstein with Annette Michelson shot-by-shot was pretty illuminating. Going through Psycho or Mouchette with Rothman; Antonioni with Ted Perry. The films got illuminated and were allowed to stand as works of art. It was the same way you’d go through a Giorgione with Panofsky if you were an art student who had such a privilege. It was really the method of Wölfflin. This method spread out across the study of visual arts and came home to roost in the study of another visual art: film.

For me, the films that are worth going back to repeatedly include key figures in the avant-garde cinema. All of that work has a formal dimension, but scholars also study film genres largely through the lens of some version of French structuralism. The genre course also involves issues of narration. And narration is largely understood by formal means, as critics do in literature, right? The models come from French formal critics like Riffaterre and Greimas, from writers like Mieke Bal, who does literary and visual arts analysis. These models have been adapted by people like Edward Branigan and David Bordwell for film study, and these critics announce such openly. So, the formal method has a lot of applications and they actually change how it feels in particular ways—that’s what we work on. The idea is to be in the dark with students and work the films in as much detail as we can, either through illustrative passages in films or working through longer stretches. That’s the basic teaching method. Sometimes it’s super-discursive and sometimes bit-by-bit.

My own teaching otherwise tends to be pretty much lecture-based. I incorporate discussion components, but I’m basically one of those lecture instructors that’s never actually relied on the Socratic method as a primary method. I’m too impatient—it’s a personality flaw. I admire and envy teachers who are dedicated to the Socratic method. I’m too much in a hurry and I’m really a coverage guy. Like, I’m really anxious for students to get the most variety of films possible. I also trust that the students, when exposed, will be touched by things, inspired by them to do things on their own, and I think that’s worked out pretty well. Students who are any good—having any critical imagination and taking the program seriously—eventually go with their own insights and their own ways of putting ideas together. You can tell in their writing. And then every academic program has lots of people who are basically bumps on a log. And the log is floating them toward their degree.

Now, there is always the question of whether an artist knows what he or she is doing, or whether their work was shaped by their biographies (which is a very popular idea in mainstream literary criticism). In film studies, critics are wary of this approach. In the case of filmmakers like Howard Hawks—those who work within a highly organized system like Hollywood or Hong Kong—I don’t tend to go to a biographical explanation. It’s interesting to know who Howard Hawks is, how he behaved in Hollywood as a personality, but not helpful in grasping his films. Most narrative filmmakers in the classical tradition hide who they are as artists behind their work and at the same time, within the weave of their work, they reveal what it is about their sensibilities that makes them artists. This is easily understood when you realize Hollywood was always deeply suspicious of filmmakers who regarded themselves as more than salaried technicians and how Hollywood took it out on directors like Orson Welles who paraded themselves as artists. It was better to take caution and hide.

On the other hand, I tend to take seriously the statements offered by experimental filmmakers. When you’re dealing with Hawks, he’d say, “It was fun to do it that way”—that’s pretty much all he has to say. Hitchcock will fulminate on the art of film, but his ideas of “pure cinema” are, to me, another way of hiding himself—even in the book he did with Truffaut. What’s interesting about Hitchcock, he does not tell you. When you read Brakhage’s Metaphors on Vision, you kind of get the sense of the project of an artist, at least the intellectual fictions that he found important to his work.

The same goes for the writings of Maya Deren, Germaine Dulac, Hollis Frampton—these people have produced a significant discourse about their art, and art in general, that we can take seriously. If their thinking constitutes their biography, then yeah, I take their biographies pretty seriously. I have mixed responses when dealing with Antonioni, Kieślowski, Tarkovsky or Tarr—any European art-film figure. In ways, their project is as mysterious to them as it is to us. I don’t think Ingmar Bergman knows why he’s such an interesting artist and can only articulate himself through his work. Pasolini, well, he says a whole lot of interesting things because he’s a really brilliant essayist who gives us insight into his work—and there’s a lot of people in between those two.

The critic of English literature feels more often than not that his or her job is to bring Spenser, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton alive to the current generation. We should understand that responsibility as a tradition that is centuries old. The philosopher has the same responsibility for Aristotle, Plato, Plotinus, Descartes, Kant. Film is rather odd in that it has a super-truncated history. When does the first artist actually appear in the cinema? Do we want to be super-generous and say Méliès? Or be more restrictive and say Eisenstein? Or are we going to be middle-of-the-road and say it’s D.W. Griffith? We’re still trying to sort out what it is that might be worth keeping, even as we recognize that pretty much nothing is going to be kept as significant art past the next fifty years.

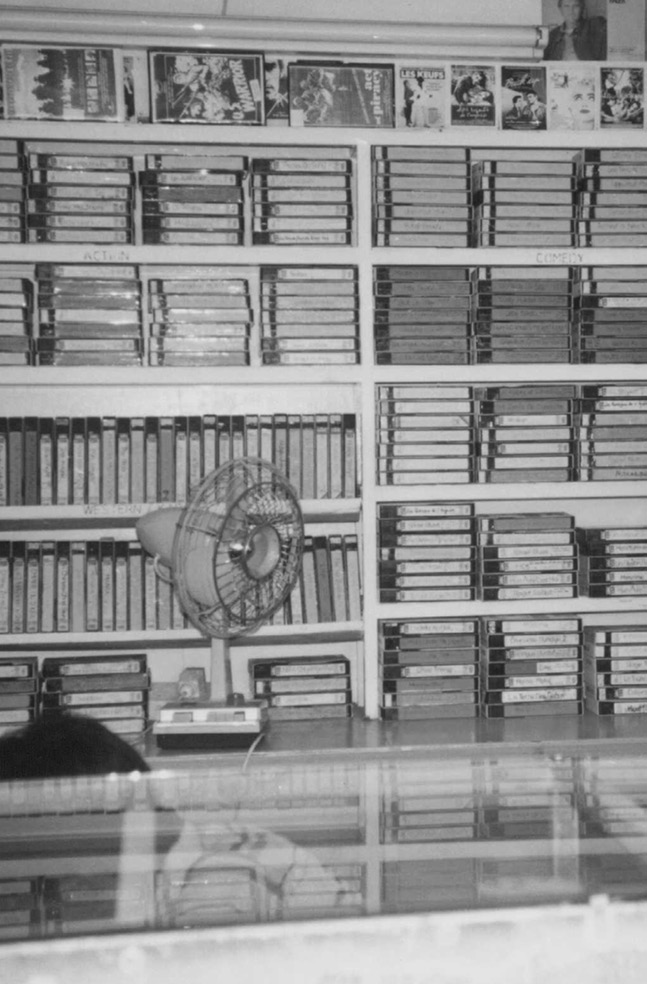

Cinema is like sand-painting (the comparison was Brakhage’s). Once it, as a physical matter, disappears… and it’s an art that’s really tied to a very fragile physical matter. Much more than half of the films made are permanently lost. Our understanding of the hierarchies of the art form—who are the important figures?—that game is doomed and everyone kind of recognizes it. The task of the critic in film is much more melancholy than the task of the critic in literature. The literary critic has reason to believe what they care about will survive. The film critic has a strong suspicion that despite everything, despite efforts of cinematheques and restorers, we’re losing this particular struggle. It’s a source of great distress when the study of video games creeps its way in to the study of cinema: it portends that we’ll have to move on from cinema to other things that amuse the young. I-don’t-care formulations like, “Why are we fetishizing celluloid?” or “Isn’t cinephilia, like its name suggests, some kind of pathology?” are all things that suggest to me that everybody’s getting ready to abandon the cinema. And that means they’re going to be abandoning the artist in the cinema, the idea of preservation for the future.

The critic of the fine arts has the advantage that the things she wishes to understand, to contextualize, are worth gazillions of dollars. Whereas with a film, which has already had its commercial run, is never worth gazillions of dollars. In fact, it’s worth very, very little. There’s no Christie’s for Antonioni prints. The cinema’s triumph resulted because it was an art made under the conditions of industrial reproduction. That same historical feature dooms it. There’s no film equivalent to an altarpiece in a small village in Italy that turns out to be a masterpiece and gets carted off to a museum in New York. I mean that’s a fetish object. There might have been a print of Nosferatu in a Danish mental hospital—and there was such a discovery twenty years ago—but there could be another in a forgotten cinema basement in Duluth, too.

The art critic can be sure that, barring the collapse of civilization altogether, there can be edition 200 of Doom or Halo and it won’t affect the cultural value of that Italian altarpiece. There’s some sense in which the moving visual culture will now say, “This is what’s happening, baby!” but not Brakhage, Antonioni or Godard. The cinema is coloured by its own obsolescence in visual culture, more so than the already-survived obsolescence of pre-Raphaelite art or the Byzantine icon. “That stuff’s gonna live on forever. Well the cinema, ehn.” As a preserver then, well, I think if you were a student in music and you didn’t know Brahms, you’d be deficient. You’d be like a doctor who didn’t know what to do with the respiratory system, only what to do with the digestive system. It doesn’t make any sense.

In cinema, the view that if you’re a kind of accredited film student you should be chasing after the Chris Markers, Antonionis and Eisensteins—that’s not really the culture, except among the few. Instead, it’ll be things coming in and out of fashion. So—and I might say this is true of critics generally—film critics generally don’t feel a responsibility for the whole thing that film is. And this is worse amongst filmmakers. Filmmakers feel no responsibility for the tradition in which they work. Those who do are exceptional.