1.1 Modelling with data

One of the simplest mathematical models is a linear one which represents the relation between two variables by a straight line graph. In some cases the variables given in the problem satisfy a linear relation, but in other situations we might have to transform the variables to obtain a straight line graph.

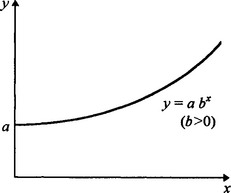

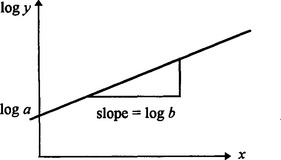

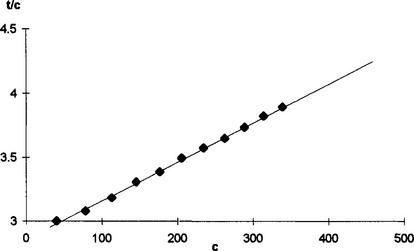

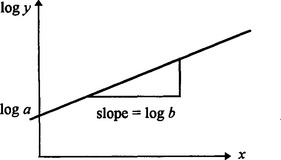

For example, a common method of transformation is the use of logarithms. If the variables x and y satisfy a power law relation, y = abx, then a graph of y against x will produce a curve as shown in Fig 1.1a. However, taking logarithms of each side gives

Fig 1.1a Graph of y against

and a graph of log y against x will give a straight line (as in Fig 1. lb). From the properties of the second graph we can estimate the values of a and b.

Fig 1.1b Graph of log y against x

In the following two examples we illustrate the graphical approach to problem solving.

EXAMPLE 1 Modelling ‘the greenhouse effect’

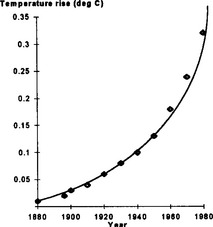

The burning of fossil fuels such as coal and oil adds carbon dioxide to the atmosphere around the earth. This may be partly removed by biological reactions, but the concentration of carbon dioxide is gradually increasing. This increase leads to a rise in the average temperature of the earth. Table 1.1 shows this temperature rise over the one hundred year period up to 1980.

Table 1.1

The temperature rise of the earth over 100 years

| Year |

Temperature rise of the earth above the 1860 figure (°C) |

| 1880 |

0.01 |

| 1896 |

0.02 |

| 1900 |

0.03 |

| 1910 |

0.04 |

| 1920 |

0.06 |

| 1930 |

0.08 |

| 1940 |

0.10 |

| 1950 |

0.13 |

| 1960 |

0.18 |

| 1970 |

0.24 |

| 1980 |

0.32 |

If the average temperature of the earth rises by about another 6°C from the 1980 value this would have a dramatic effect on the polar ice caps, winter temperature etc. As the polar ice caps melt, there could be massive floods and a lot of land mass would be submerged. The UK would disappear except for the tops of the mountains!

Find a model of the above data and use it to predict when the earth’s temperature will be 7°C above its 1860 value.

Solution

In this problem the variables are

• the temperature rise of the earth above the 1860 figure, T, and

• the year, n.

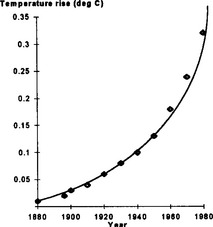

There is no simple way of discovering a relation between the temperature rise and the year by pure thought There are many complicated processes going on in the atmosphere, and the effect on the atmosphere of burning fossil fuels will involve several physical laws and chemical reactions. However, we can make progress by representing the data graphically. It is probably quite clear to you that this set of data will not lead to a straight line graph and Fig 1.2 emphasises this point.

Fig 1.2 Graph of T against n

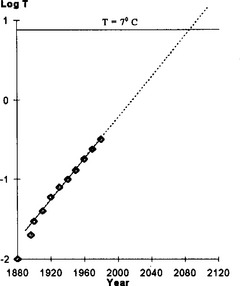

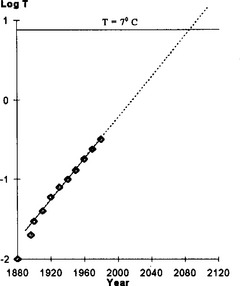

The graph of T against n is clearly not linear. However the points look close to a smooth curve passing through the origin. So we try to ‘straighten the curve’ by using logarithms. For example, if we plot log T against n we do indeed obtain a straight line graph through most of the data. The points at the lower end do not fit this straight line very well. (A simple explanation is that the data on temperature rise is correct to two decimal places. Clearly at the lower end the maximum percentage error in the data is much larger than that elsewhere. The temperature rise of 0.01 could be anything between 0.005 and 0.015 giving a maximum percentage error of 50%.

However the maximum percentage error for a temperature rise of 0.24 is 2.5%.

From the graph in Fig 1.3 we can now predict when the temperature of the earth will be 7°C above the 1860 value. Drawing a horizontal line through the value log 7, we find a value for n as 2078. What we are saying is that if this linear relationship between log10T and n is value for values of n outside the given range then in approximately 80 years time much of the UK will be flooded.

Fig 1.3 Graph of log T against n

A sobering thought! Worried? Well you should be!

If you are 20 years old then what happens in 80 years time may be of little consequence; however, it will affect the children and grandchildren of the next generation. And of course the flooding will not suddenly happen but will occur over a period of many years before 2078.

But let’s look at another problem that uses similar mathematical problem solving skills.

EXAMPLE 2 World Record for the Mile

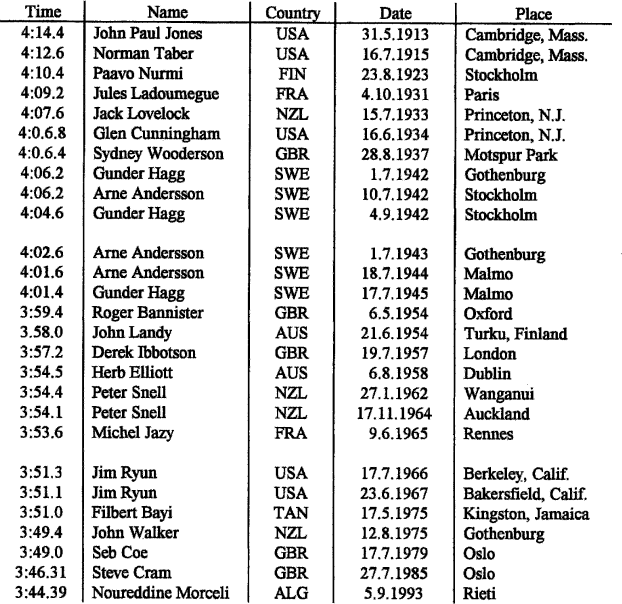

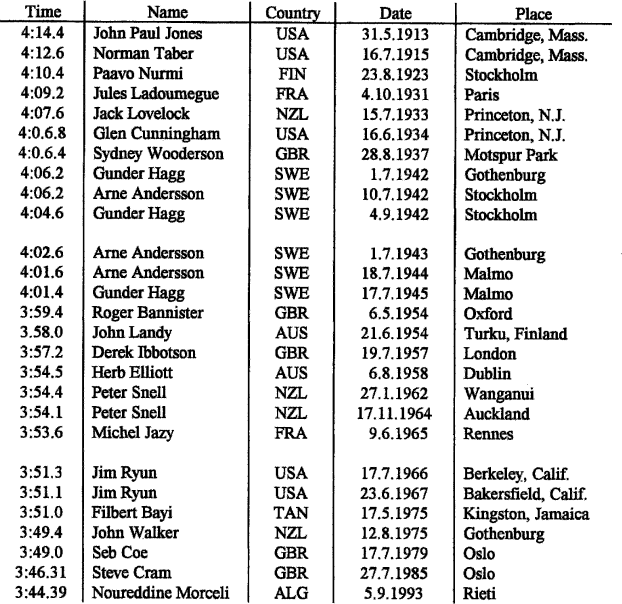

Table 1.2 shows the world record for the mile in minutes and seconds between 1913 and 1986

Table 1.2

The world record for the mile

Athletes continue to run the mile faster and faster as the years go by, but a mile in one minute, say, would seem to be impossible. Using the data estimate when it is likely that the mile could be run in 3 minutes 40 seconds.

Solution

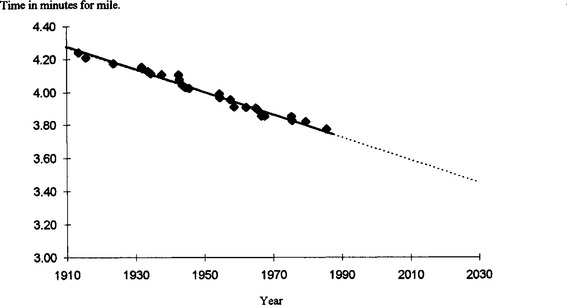

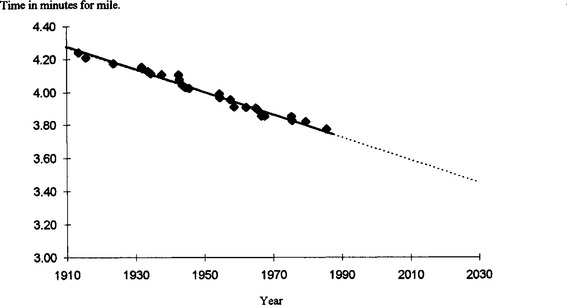

If we draw a graph to represent the data in this problem then it is surprising how close to a straight line are the data points (see Fig 1.4)

Fig 1.4 A graph of the world record for the mile

The graph is quite reasonably linear and from it we can predict that a mile run in 3 minutes 40 seconds could be achieved around the year 2000. We can continue the prediction process to suggest that a 3 minute 30 second mile will be run in about 30 years time in the year 2028. (To make these predictions we are assuming that the linear model holds true outside of the given data points).

We will have to wait to see how reasonable are these predictions. However Problems 1 and 2 suggest that a 3.5 minute mile will be achieved before the UK is flooded!

This method of solving real problems is fairly straightforward. We collect (or are given) data associated with a physical situation and use the data to draw a graph to represent the situation. Suppose that we label the variables x and y. We usually try one of three graphs in attempting to get a straight line between the variables:

• a graph of the variables, y against x, (for example Fig 1.4)

• a graph of the logarithm of one variable against the other (for example Fig 1.3)

• a graph of the logarithm of one variable (log y) against the logarithm of the other (log x)

Of course, if none of these leads to a straight line graph it does not mean that there is not a simple relationship between the variables. But finding the relationship may not be so easy.

The graph that we have drawn is an example of a mathematical model. We can use the graph to obtain a relation in symbols. For instance in Example 2, the equation,

where t is the time in seconds and T is the number of years beyond 1910 is a good fit to the straight line graph. Then the equation is another example of a mathematical model. In this way we are translating the problem from the real world situation to the rules and properties of the world of mathematics sometimes called the mathematical world. When the problem solving process is data driven as in Examples 1 and 2 we call the model an empirical model and the process of finding an empirical model is called empirical modelling.

TUTORIAL PROBLEM 1 Mathematical Models

List the mathematical structures that could form mathematical models.

TUTORIAL PROBLEM 2 Kepler’s Third Law

Table 1.3 shows the distance of each of the planets from the sun (measured in millions of kilometres) and the time (measured in days) that it takes each planet to travel round the sun once, this time is called the period.

Table 1.3

Planetary periods and distances from the sun

| Planet |

Distance from the sun R(106) (km) |

Period of revolution around the sun, T (days) |

| Mercury |

57.9 |

88 |

| Venus |

108.2 |

225 |

| Earth |

149.6 |

365 |

| Mars |

227.9 |

687 |

| Jupiter |

778.3 |

4 329 |

| Saturn |

1427 |

10 753 |

| Uranus |

2870 |

30 660 |

| Neptune |

4497 |

60 150 |

| Pluto |

5907 |

90 670 |

Use this data to find a mathematical model that relates the distance and the period. This is called Kepler’s third law of motion for the planets, and was published in 1619.

In 1601, the German astronomer Johann Kepler became the Director of the Prague Observatory. After studying the motion of the planet Mars, in 1609 he formulated his first two laws for the motion of the planets:

1. each planet moves on a ellipse with the sun at one focus

2. for each planet, the line from the sun to the planets sweeps out equal areas in equal times.

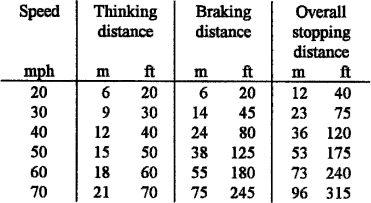

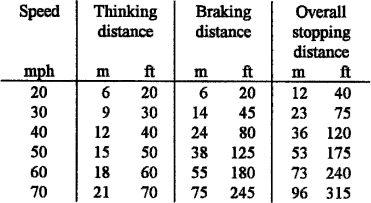

TUTORIAL PROBLEM 3 Highway Code Distances

Table 1.4 shows the safe stopping distances for cars recommended by the British Highway Code.

Table 1.4

Highway Code recommended stopping distances

Use these data to find mathematical models relating the various stopping distances and the speed of the vehicle.

The Highway Code gives certain conditions for the data to be appropriate. Find these conditions and discuss how your mathematical models are affected by them.

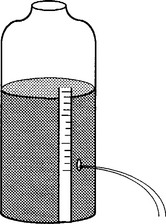

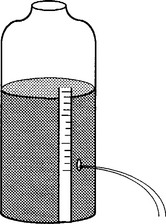

TUTORIAL PROBLEM 4 A leaking bottle

Take a plastic (see through) bottle and make a small hole near the base. Attach a vertical scale to the side of the bottle so that, when it contains water, you can read the height of the water surface in the bottle above the hole.

Cover the hole with your finger and fill the plastic bottle with water to the top of the scale. Remove your finger so that the bottle leaks water.

By collecting appropriate data, find an empirical mathematical model relating the height of water in the bottle above the hole and the time that has elapsed since the hole was uncovered.

Fig 1.5 A leaking bottle experiment

TUTORIAL PROBLEM 5 Bode’s Law

The solar system consists of the sun, the nine planets together with many smaller bodies such as the comets and the meteorites. The nine planets are, in order of distance from the sun, Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto. Between Mars and Jupiter are many very small bodies called the minor planets or Asteroids and nearly all of them are too small to be seen by the naked eye from the earth. Tutorial Problem 2 was about Kepler’s laws for the motion of the planets.

This problem is about an 18th century law called Bode’s law and relates the distance of a planet from the sun to a number representing the planet. Table 1.5 gives the average distance of the planets from the sun and the ratio of these distances to the earth’s distance from the sun.

Table 1.5

Data for Bode’s law

| Planet |

Distance from the sun R(106) (km) |

Ratio R/Re where Re is the earth’s distance from the sun |

| Mercury |

57.9 |

0.39 |

| Venus |

108.2 |

0.72 |

| Earth |

149.6 |

1.00 |

| Mars |

227.9 |

1.52 |

| Asteroids |

433.8 |

2.9 |

| Jupiter |

778.3 |

5.20 |

| Saturn |

1427 |

9.54 |

| Uranus |

2870 |

19.2 |

| Neptune |

4497 |

30.1 |

| Pluto |

5907 |

39.5 |

Ignoring Mercury, we assign a number to each planet in the following way:

• for Venus choose n = 0

• for Earth choose n = 1

• .

• .

• .

• for Pluto choose n = 8

Use the data to find a model relating R / Re and n. What value of n should you give to Mercury so that it too fits the model?

TUTORIAL PROBLEM 6 How much tape is left?

Most audio cassette recorders have a numerical tape counter which allows the user to create a numerical index for the items on the cassette tape for playback purposes. Furthermore, it is often convenient to be able to relate the number displayed on the tape counter with the playing time remaining, for example when needing to use the cassette to record a known length of music.

Does the counter on the machine operate so that the counter reading is directly proportional to the playing time, or does it count the number of revolutions of the take-up spool?

For example, for a C90 cassette (45 minutes playing time each time) the tape counter on my cassette deck goes from 0 to 600 for each side. Does it take 15 minutes to reach 200? When the counter reads 400 are there 15 minutes of playing time remaining?

For a cassette player equipped with a tape counter, formulate a mathematical model that describes the relationship between the counter reading and the amount of playing time that has elapsed.

TUTORIAL PROBLEM 7 The period of a pendulum

If you have seen a pendulum clock (for example a ‘grandfather clock’) you will realise that there must be a relationship between the period of swing and the effective length of the pendulum.

Set up a simple ‘bob pendulum’ using a heavy mass and a length of string. Measure the period of small swings for different lengths of the pendulum. Use your data to find a mathematical model that relates the period of the pendulum and the length of the string. Does the result depend on the mass of the bob?

Fig 1.6 A ‘bob pendulum’

1.2 Using Mathematical Models

There are many types of problem that you will have tackled using mathematics. Mathematical problems are often set to develop and practice a mathematical skill. For example,

is an example of a mathematical problem or ‘exercise’ which in this form has little relevance to any applications in the real world. Mathematical investigations are used to explore areas of mathematics which might be new to the learner. For example,

Start with any 4 digit number where the digits are not all the same.

Rearrange them in ascending and descending order and subtract the smaller from the larger.

Repeat this with the number you obtain from the subtraction and continue. You will know when to stop.

Try different starting numbers and investigate how long a chain of numbers you can obtain.

is an example of an investigation which for many provides an illustration of mathematics as a subject in its own right. Real problems are used to illustrate the powerful application of mathematics to solve problems set in the real world. For example in section 1.1 the problem concerning the ‘greenhouse effect’ is a problem about the world in which we live. We can use mathematics to attempt to solve many problems of this type. To distinguish between mathematical exercises, mathematical investigations and applications of mathematics to the real world we will call the latter ‘real world problems’ and then mathematical modelling is the process for tackling such problems.

When using mathematics to solve real world problems one of our aims is to obtain a mathematical model that will describe or represent some aspect of the real situation. For example in Example 2, the world record for the mile was modelled by a graph and by an equation. Both of these models describe the relationship between the world record and the years between 1910 and 1990. Having found a mathematical model, we then use the model to predict something about the future. For example we were able to predict that a mile might be run in 3.5 minutes in the year 2028.

The formulation of a mathematical model can be a challenging task in many problems. Empirical models are fairly easy to find providing that we are given or can collect the data from appropriate experiments. But this problem solving process has severe limitations in the validity of our interpretations from the graph.

As an illustration of the caution needed when using an empirical modelling approach we consider Examples 1 and 2 again. Table 1.6 shows the predictions that we made in each case:

Table 1.6

Predictions from Examples 1 and 2

| Problem |

Predictions |

| Greenhouse effect |

UK flooded in 2078 |

| World Record for the mile |

3 minute 40 sec mile in year 2002 |

|

3 minute 30 sec mile in year 2028 |

At first sight these predictions may be reasonable, after all the curve through the data in Example 1 seems smooth and the straight line for Example 2 appears to fit the points well. If the predictions are reasonable then the ‘greenhouse effect’ should be a cause for concern. However, consider the world record for the mile. If we extend the line on the graph until it crosses the year axis then we can predict that ‘by about 2582 the mile will be run in no time at all’ i.e. the zero minute mile!! Clearly this method of approach is not very reliable. It is more likely that there is a curve through the data that gradually levels off to some limiting value and the straight line model only applies to a portion of the data.

So what concern should we have about the flooding of the UK? Unfortunately too many non mathematicians use this problem solving approach to cause alarm and to make false predictions. We should treat the solutions of Examples 1 and 2 with caution. Perhaps a 3.5 minute mile around the year 2028 is a reasonable prediction - it is not going too far beyond the range of the given data. However, the UK being flooded in the year 2078 is probably not a good prediction at all. In making this prediction we must assume that the rate of fossil fuel burning continues over the next hundred years as it has been over the past one hundred years. This is clearly unlikely. The production of electricity using different fuels to coal/oil is one example of changes that will occur. Industry and homes burn less coal and oil as the prices of these fuels have risen sharply during the past two decades. The motor car will eventually use a different polluting fuel that petroleum. It is interesting that in the mid-19th century there was concern that if the amount of horse manure dropped by horse drawn vehicles in London continued to increase at the then rate, the streets of London would be full of manure up the height of the highest building. This did not happen! Instead the motor car replaced the horse and a different pollution problem has occurred. So in one hundred years time the future generations may look back and smile at our concern over the ‘greenhouse effect’ - they will however have their own pollution problems!

To include changes in the important features of a problem in formulating our mathematical model requires a different problem solving process, one based more on theory than on data alone. This is called theoretical modelling. We introduce this in the next section.

The message of the first two sections is that, although formulating models (i.e. expressing relations between variables) using data is reasonably straightforward, and important as a problem solving tool, the method has severe limitations. We must list carefully the assumptions that are explicit to the model, and consider if and by how much, they may change before asserting the ‘goodness’ of any predictions.

Already in these two sections we have introduced three of the important skills in problem solving:

• understand the problem,

• be aware of the assumptions and simplifications made in solving the problem,

• question the results or predictions of the model.

The last skill is more than just saying “have I got the answer correct?” and “look in the back of the book”! The mathematical answer might be perfectly correct but the interpretation in the context of the real world is meaningless e.g. “a zero-minute mile will be run in the year 2582” is ‘correct’ mathematically but clearly nonsense physically.

TUTORIAL PROBLEM 8 Interpreting model predictions

Consider again the Tutorial Problems 2-7. List the assumptions and simplifications made in solving the problems and criticise the appropriateness of predictions.

TUTORIAL PROBLEM 9 Hooke’s Law

You will need an elastic string or spring, masses and a support stand.

By hanging different masses from the ends of the elastic string or spring, formulate a mathematical model between the mass and the extension of the string or spring.

List the assumptions and simplifications made in formulating your model.

Discuss an improved model for the stretching of an elastic string or spring.

1.3 Modelling from Theory

In sections 1 and 2 we presented two examples showing the problem solving process based on formulating data-driven models and we discussed some of the drawbacks when making predictions based on this approach. The next three examples are intended to help you to gain an understanding of problem solving that uses a more theoretical approach. In each case notice how the data is used after the model is formed to help to check the validity of the model.

EXAMPLE 3 The need for a pedestrian crossing

As a pedestrian there are many times in a day that you have to cross a road. For some roads, which do not carry much traffic you wait for a gap between cars and then cross; for more busy roads you are advised to cross at a zebra or pelican crossing. The local council has to decide whether and when to install controlled crossings on certain roads. This problem investigates road crossing strategies.

Formulate a mathematical model for crossing a one-way street so that a pedestrian can cross the road safely. Use your model to decide under what conditions a local council decides to install a pedestrian crossing.

SOLUTION

There are many factors which will affect the decision of the Local Council from cost through to the environment in which the road is part. Intuitively it is reasonable to think that the introduction of a pedestrian crossing will be dependent on the amount of road and pedestrian traffic. However other factors which are more difficult to quantify mathematically may have a more important bearing on the decision. For example, if the road is close to a hospital or a school then the decision to include a pedestrian crossing may not depend on the quantity of traffic but depends on the type of pedestrian traffic.

For a simple mathematical model consider the following assumptions and simplifications:

1. the road is one-way, a single carriageway and straight with no obstructions for the positioning of a pedestrian crossing,

2. the speed of the traffic is constant and equal to the road speed limit,

3. the density of the traffic is constant,

4. the pedestrians walk across the road at a constant speed.

The first statement ensures that when we have a simple mathematical model (based on assumptions 2, 3 and 4) the Local Council can install a pedestrian crossing without considering the environment. To formulate a mathematical model we need to introduce symbols to represent the physical quantities. The following table shows this information:

Table 1.7

The important variables in the problem

| physical quantity |

symbols |

units |

| width of the road |

w |

metres |

| speed of the pedestrians |

v |

metres per second |

| time interval between the traffic |

T |

seconds |

The time for a pedestrian to cross the road is w/v and the time between two road vehicles is T. A simple model in words is

and then in symbols we have

This is a condition for the pedestrians to cross the road safely. If we reverse the inequality then we have a simple condition for the need of a pedestrian crossing.

To get a feel for the values in this inequality we need some data.

For the vehicle data suppose that the road is in a 30 mph (13.3 m/s) speed limit area and the vehicles travel at the safe distance recommended by the Highway Code (23 metres). With these values the time interval between the vehicles is 23/13.3 = 1.73 seconds.

For the pedestrians suppose that their speed is 4 mph (1.77 m/s) and the width of a single carriageway is 3 metres. The value of w/v is then 3/1.77 = 1.69 seconds.

With this data the advice to the council might be not to install a pedestrian crossing. However, the model is very simple and subject to many criticisms. For example

• the traffic is unlikely to be evenly spaced at the Highway code recommended distance;

• a safety margin of 0.04 seconds is not really realistic;

• the model suggests that you can either cross or not cross which is not realistic, the question of how long to wait does not enter the problem;

• 4 mph is quite a fast walking speed, especially for elderly people.

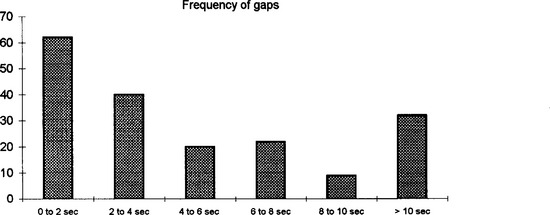

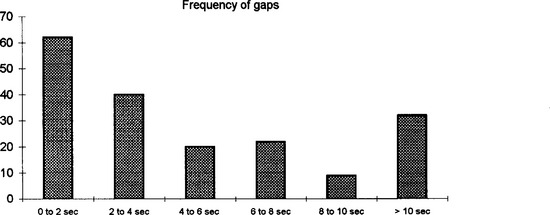

A more complicated and perhaps more realistic model is to assume that a pedestrian crossing will be installed when the probability of a gap of time interval greater than w/v is less than some predetermined value. The data for this model must show more detail than for the simple model above. Fig 1.8 shows the data collected by a group of students on a road in Plymouth during a thirty minute period.

Fig 1.8 frequency distribution of time gaps between cars on one carriageway of a Plymouth road

The probability of a gap of time interval greater than 2 seconds (this allows for a good safety margin) is calculated as the ratio

The model says that the road needs a pedestrian crossing when the probability p is less than some predetermined value po.

The model could be developed further by considering

• the variability of the speed of the pedestrians;

• a statistical model involving the arrival times of cars and pedestrians.

There are several points to notice about this problem solving activity.

• The first model is very simple and straightforward, however it does allow us to obtain a better understanding of the problem and helps us to ‘get into the problem’. An important saying in problem solving is “a simple model is better than no model at all”.

• In the first model there is a need for data to test or validate the model and in the improved model the data for a particular road is an important part of the formulation of the model.

• Each model that is formulated depends on certain assumptions and simplifications chosen by the problem solver. This allows different people to formulate different models and how good the models are can be tested at the validation stage with appropriate data.

• The mathematical model starts with a word description or a word model in each case. We then move from the words to the symbols which have been defined along with their units.

• The process of solving the problem is an iterative one; i.e. we start with a simple approach and them gradually refine it by looking back at the assumptions and simplifications.

EXAMPLE 4 Icing Cakes

A wedding cake is to be baked in a square cake tin and will have a volume (before icing) of 4000 cm3. Determine the dimensions of the cake which will give the minimum surface area for icing (i.e. the top and the four sides).

Find the dimensions if the cake is baked in a circular tin.

There is a rule of thumb in cookery that one third of the marzipan should be used for the top of the cake and the remaining two thirds for the sides. Investigate the validity of this rule of thumb.

SOLUTION

The assumptions and simplifications for this problem are quite straightforward and will lead to the ‘perfect cuboid or cylindrical cake’.

• The cake fills the tin exactly after baking and does not crumble or stick to the sides;

• each cake is perfectly flat on top and bottom so that it does not rise above the top of the cake tin;

• the mixture of volume 4000 cm3 includes any air bubbles etc.;

• the marzipan goes on the cake before the icing.

1. Consider the square cake tin first. Let the sides of the cake have length x cm and the depth of the cake have length y cm.

The volume of mixture in the tin is

and the surface area to be marzipanned and iced is

Eliminating y between these two equations gives

The mathematical problem is to find the value of x which gives the minimum value for S. There are several ways to do this, for example

• by calculus, using differentiation;

• drawing a graph using a calculator or spreadsheet.

Whichever method you prefer, the minimum value of S (= 1200 cm2) occurs when x = 20 cm and then y = 10 cm.

The dimensions of a square cake with minimum surface area for icing is 20 cm × 20 cm × 10 cm.

2. Consider the circular cake tin. Let the radius of the cake be r cm and the depth of the cake be y cm.

The volume of mixture in the tin is

and the surface area to be marzipanned and iced is

Eliminating y between these two equations gives

The minimum value of S is given by r = y = 10.84 cm (correct to 2 d.p.).

The test for the rule of thumb for the use of the marzipan is shown in the following table

Table 1.8

Testingthe rule of thumbfor icing a cake

So the ‘rule of thumb’ works for the minimum area of perfectly shaped cakes.

When testing this model two students at the University of Plymouth made the following observation:

“The model really ought to be tested with real data to see if it was as accurate as we thought. Fortunately a cake tin of the size 20cmx20cmx10cm was found and a cake which had just been baked was used for the tests. On conclusion of the baking various things were found which tended to contradict the model Firstly the cake had risen quite considerably in the middle and so was not flat on top - this of course changed the shape of the cake. Also the cake was rounded off on the corners and so was not perfectly square in shape. Also the cake contained a lot of air bubbles and was not smooth as we had assumed.

When testing the rule of thumb it was found that the proportion of marzipan used on the top was in fact slightly greater than a third (more like 40%) although this was very difficult to measure.”

The students have provided a good criticism of the model and the next stage would be to attempt to improve the model by including the feature that most cakes have a curved surface and are not perfectly flat.

EXAMPLE 5

Most audio cassette recorders have a numerical tape counter which allows the user to create a numerical index for the items on the cassette tape for playback purposes. Furthermore, it is often convenient to be able to relate the number displayed on the tape counter with the playing time remaining, for example when needing to use the cassette to record a known length of music.

For a cassette player equipped with a tape counter, formulate a theoretical mathematical model that describes the relationship between the counter reading and the amount of playing time that has elapsed.

SOLUTION

In section 1.1 you solved this problem empirically by collecting data from an audio cassette recorder and drawing appropriate graphs. In this example we formulate a model from theory and then use the data to test the model.

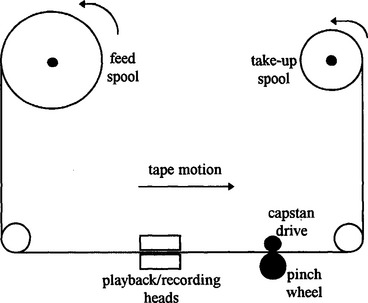

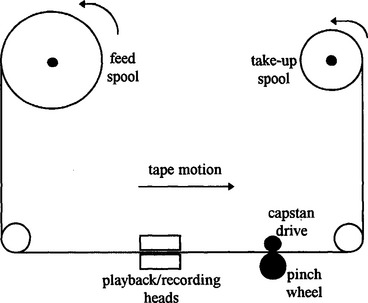

To begin the formulation process we need to understand how the counter mechanism functions. Fig 1.9 shows a simple drawing of the mechanism of an audio cassette player. The tape leaves the supply spool, passes over the playback/recording heads at a constant speed and is collected up by the take-up spool. The constant speed is maintained by the capstan drive and pinch wheel. Since the tape speed across the heads needs to be constant the supply and take-up spools change speed during the playing (or recording) of a tape. We will assume that the tape counter is connected directly to the take-up spool.

Fig 1.9 A simple view of the mechanism of an audio cassette player

From this introduction we deduce that the following features are important in formulating a mathematical model:

time elapsed

length of tape on the take-up spool

radius of the take-up spool when empty

radius of the take-up spool at general time

thickness of the tape

speed of the tape across the heads

counter reading

number of turns of the take-up spool

angle turned through by the take-up spool

As in the previous two examples the problem solving process begins with a list of assumptions and simplifications.

1. the speed of the tape across the heads is constant

2. the tape has constant thickness

3. the counter reading is a continuous variable

4. the counter reading number is proportional to the number of turns of the take-up spool

With these assumptions we can now proceed towards a mathematical model. In this example the model will consist of three sub-models for different parts of the system. This is a common feature of more complicated real problem solving activities. But first we define the variables, these are shown in the following table:

Table 1.9

The variables and parameters for the tape counter model

| physical quantity |

symbol |

units |

| elapsed time |

t (variable) |

seconds |

| radius of the take-up spool at time t |

r (variable) |

cm |

| radius of the empty spool |

r0 (parameter) |

cm |

| length of tape on the take-up spool |

L (variable) |

cm |

| thickness of the tape |

h(parameter) |

cm |

| counter reading |

c(variable) |

|

| angle turned through by the take-up spool at time t |

a(variable) |

radians |

| speed of the tape across the head |

v(parameter) |

cm/s |

Note that in this table some of the quantities have been labelled as variables while others (r0, h and v) are called parameters because they remain constant for a particular cassette player and tape; however if you change player and/or tape then the values of these quantities could change.

1. As the tape passes over the head at constant speed we have

2. Assumption 4 above states that the counter reading number is proportional to the number of turns of the take-up spool and since the number of turns is essentially the total angle turned through we have

where k is a constant of proportionality.

Our aim is to formulate a model relating c to t, so the next step is to find a relation between L and a. To do this we consider the length of tape added to the take-up spool δL, when it rotates through a small Tangle δa.

Fig 1.10

(1)

(1)

Each time the take-up spool makes one complete revolution the angle a increases by 2π and the radius of tape on the spool increases by the tape thickness h. So, using a proportionate argument, if the angle increases by δa then the radius will increase by δr = hδa / 2π. In the limit as δa tends to zero we have the differential equation

which has the solution

Substituting in equation (1) and letting δa tend to zero we have

Integrating (and using the initial condition L = 0 when a = 0)

and finally substituting a by c/k and L by vt and rearranging we have

This is a mathematical model relating the elapsed time t and the counter reading n. Note that it is non linear which agrees with your empirical approach in Tutorial Problem 6.

To validate the model we need to use data collected from an audio cassette player. Table 1.10 shows the data from an experiment carried out by a group of students at Plymouth. The radius of the spool was measured with a ruler and the constant of proportionality k (for the equation c = ka) was calculated from the number of turns of the take-up spool for the counter reading to increase by 100 (approximately 190 complete turns).

Table 1.10

Counter readings and elapsed time for an audio cassette player

| time t, (minutes) |

counter reading, c |

ratio t/c |

| 0 |

000 |

|

| 2 |

040 |

3.000 |

| 4 |

078 |

3.077 |

| 6 |

113 |

3.186 |

| 8 |

145 |

3.310 |

| 10 |

177 |

3.390 |

| 12 |

206 |

3.495 |

| 14 |

235 |

3.574 |

| 16 |

263 |

3.650 |

| 18 |

289 |

3.737 |

| 20 |

314 |

3.822 |

| 22 |

339 |

3.894 |

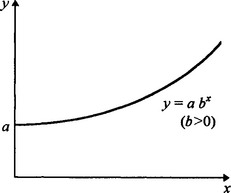

We could draw a graph of t against c but it would not be as clear as a straight line graph; however if we divide each side of the model equation by c we obtain

(2)

(2)

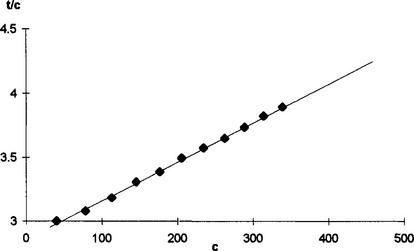

This equation suggests that a graph of t/c against c should be a straight line. Fig 1.11 shows this graph for the data in Table 1.6 and a straight line looks a good fit.

Fig 1.11 A graph of t/c against c for the tape data in Table 1.10

The values for the slope and intercept of the graph are 0.00315 and 2.832 respectively. From equation (2) and the values for h, v, k and r0 we have

The agreement between the model and the data is remarkably good. So we conclude that there is no need for an improvement to the mathematical model in this example.

List the important features that you think will be involved in formulating the model, list the assumptions and simplifications and criticise your model making appropriate suggestions for improvements.

TUTORIAL PROBLEM 10 Ropes and Knots

Tying a simple overhand knot in a rope will shorten it. Formulate a mathematical model between the shortening of the rope and its diameter. You should formulate your model without taking any measurements. However when you have a model then use ropes of different diameter to validate your model.

List the important features that you think will be involved in formulating the model, list the assumptions and simplifications and criticise your model making appropriate suggestions for improvements.

TUTORIAL PROBLEM 11 Length of a Toilet Roll

You are provided with a roll of toilet paper. Formulate a mathematical model to predict its length.

List the important features that you think will be involved in formulating the model, list the assumptions and simplifications and criticise your model making appropriate suggestions for improvements.

TUTORIAL PROBLEM 12 To Buy or Rent a TV

A person wishes to acquire a colour television set. The problem is “should the set be bought or rented?.”

List the important features that you think will be involved in formulating the model, list the assumptions and simplifications and criticise your model making appropriate suggestions for improvements.

TUTORIAL PROBLEM 13 Second Hand Cars

The purchase of a hew or second hand car is a major item of expenditure for most people. Some people always buy a new car, others always buy second hand cars. Again, some people change their cars frequently, say every two or three years, while others keep their cars for much longer, perhaps even when they are no longer roadworthy. By carefully considering the economics of car ownership one should be able to decide what is the best policy on changing one’s car; whether to buy a new car or a second hand one, and in the latter case how old a car to buy and how long to keep it before trading it in.

Analyse the economics of car ownership, and decide on a strategy of how old a car should be when bought and for how long it should be kept.

List the important features that you think will be involved in formulating the model, list the assumptions and simplifications and criticise your model making appropriate suggestions for improvements.

TUTORIAL PROBLEM 14 Raffles

You are organising a raffle for a charity. The prizes will have to be paid for from the money raised by the sale of the tickets, and you have to decide the cost of the tickets and the value of the prizes. For a small prize, people would naturally only be willing to pay a small amount for a ticket, whereas for a large prize they would be willing to pay more.

Formulate a mathematical model to help you to decide the size of prize and the cost of the tickets.

List the important features that you think will be involved in formulating the model, list the assumptions and simplifications and criticise your model making appropriate suggestions for improvements.

Summary

This Chapter has introduced two approaches to problem solving. The first, leading to empirical models, relies on collecting (or using given) data and working from a graph. Although reasonably straightforward, and important as a tool, the method has severe limitations. We must list carefully the assumptions that are implicit to the model, and consider if, and by how much, they may change before asserting the “goodness” of any prediction.

In this section we have considered a more theoretical approach and you should notice how different the approach is to solving Examples 3 to 5 compared with Examples 1 and 2. The theoretical problem solving method is much more than just drawing graphs or solving equations. It contains the following steps:

• understand the problem

• identify the important features

• make assumptions and simplifications

• define variables

• use sub-models

• establish relationships between variables

• solve the equations

• interpret and validate the model (i.e. question the results of the model)

• make improvements to the model

• explain the outcome

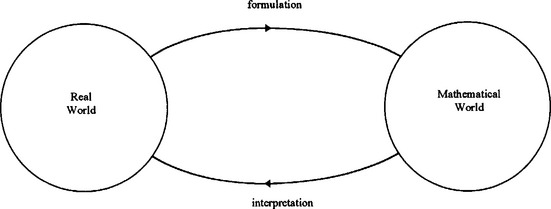

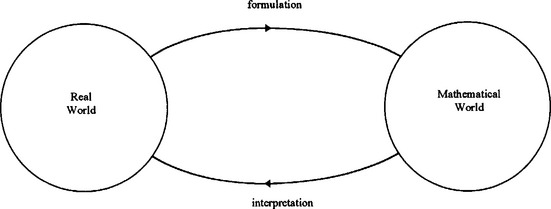

The process of using these steps to solve a real world problem is called mathematical modelling. The process has essentially three phases; we formulate the mathematical model by describing or representing the real world in terms of mathematical structures (such as graphs, equations, inequalities, lising carefully the assumptions we make). We solve any equations that may occur (for example, in the tape recorder problem we needed to solve two differential equations). Then we use appropriate data to test the goodness of the model. In doing this we have interpreted the results of the mathematical analysis and criticised the model hopefully suggesting improvements to the model. This process is illustrated in Fig 1.12.

Fig 1.12 A simple view of Mathematical Modelling

In the next two chapters we develop this schematic view of modelling more fully.