CHICAGO’S LITTLE ITALIES

A map of the city of Chicago circa 1920.

Double indexed street map of Chicago/Fred Wild Company/via Wikipedia Commons

The Chicago that Antonio Pasin arrived at in 1914 was a place filled with the raw realities of industry and overpopulation. The city had more than a dozen Little Italies, creating a map across the city that replicated the same regional divisions that had existed in the home country, as workers accumulated savings to send to their relatives back there. Southern Italians gathered in “Little Sicily” on the North Side of the city, most Tuscans came together in the “Heart of Italy” on the city’s Lower West Side, and people from northern Italy, including Antonio, settled in “Little Venice” on the West Side of the city. Every community had its own heritage, and gradually these neighborhoods became famous for their vibrant culture, food, and dancing.

Like most immigrant laborers who were new to the city, Antonio lived in a boardinghouse. It was near West Grand Avenue, where he could walk to the nearby industrial areas of the city to look for work. It was common for boardinghouses to double their capacity by assigning two workers to a bed to sleep “hot bed” shifts, alternating between their day and night labor schedules.

“The boardinghouse felt like a human beehive. One was a poor man among the poor. The meals were poor, and we mostly waited around learning to pronounce the English word ‘work.’”

—ANTONIO PASIN

Work was often the only common factor among these new residents of Chicago’s Italian communities. Italian labor contractors, called padrones, acted as middlemen to find newcomers work and broker deals. Many of them were fair, and many of them were not. But without any formalized unions or connections beyond whatever family members had come over with them, most Italian peasants, or paesani, had little choice. The padrones shipped workers seemingly at random to construction sites all across the city, primarily to work on massive public works projects. Previous craftsmen who had been trained as artisan masons and woodworkers took jobs as bricklayers and railroad track layers.

Antonio’s first job was carrying water for a sewer-digging crew. His next job was for a railroad company, where he was employed to carry wooden crossbars to the farthest extremities of new tracks reaching out from the city’s central nervous system. Immigrant work was primarily subterranean, and Antonio began working in the depths of the city’s factories, sending his wages home to his parents to help them to buy back the family home. He described this time in his journal as “bestial” and “with minimal pay.” Indeed, the average annual salary for Chicago’s immigrant workers at the time was about $650, equivalent to $16,000 in today’s dollars.

“Before I came to America, I thought the streets were paved in gold. When I came here I learned three things: The streets were not paved in gold, the streets weren’t paved at all, and I was expected to pave them.”

—ITALIAN IMMIGRANT CIRCA 1915

Antonio passed an American piano factory every day on his way to work. One day he got up the courage to go in, hoping he would be given the opportunity to show off his woodworking skills. The owners quickly dismissed him; still only seventeen years old, he was too young and they were not looking for any apprentices. It also didn’t help that he did not speak English. But now that Antonio had seen the inside of the factory, which reminded him of working in his father’s woodshop in Italy, he saw the possibility he was hoping for and did not back down. He bought an Italian-English grammar book and began to study in the evenings, smudging the pages with his dirty fingers and practicing writing his rudimentary vocabulary in the margins. He studied relentlessly the phrases he needed to make himself understood and returned to the piano factory to ask for a job. The owner of the factory hired him as an assistant in charge of the circular saws. This was Antonio Pasin’s first small triumph—pulling himself out of the tunnels and into the light of day by his own initiative. It was also his first lesson in what it would take to make it in America—not only hard work, but the willingness to take a risk, which would serve him as he prepared to set out on his own.

A LETTER from HOME

For almost two years, Antonio worked hard at every job he held, sending whatever remained of his wages each month to his family to help them buy back their home, which they had lost. Sometime in 1916, Antonio received this letter:

The beginning of the first letter Antonio received from his father in Italy. Before he left home, Antonio planted several trees outside of the house as a promise that he would eventually return to see them fully grown.

Antonio, now eighteen years old, cried when he read the letter. He described it in his journal as “the letter of victory.” He would not be permitted to return to Italy until after the Great War was over in 1918. But he had tasted what was possible in America—that if you worked hard and had initiative, then you would get the opportunities you needed to make it—and knew then that he would not return home when the war finally ended. He still had to make a name for himself in America.

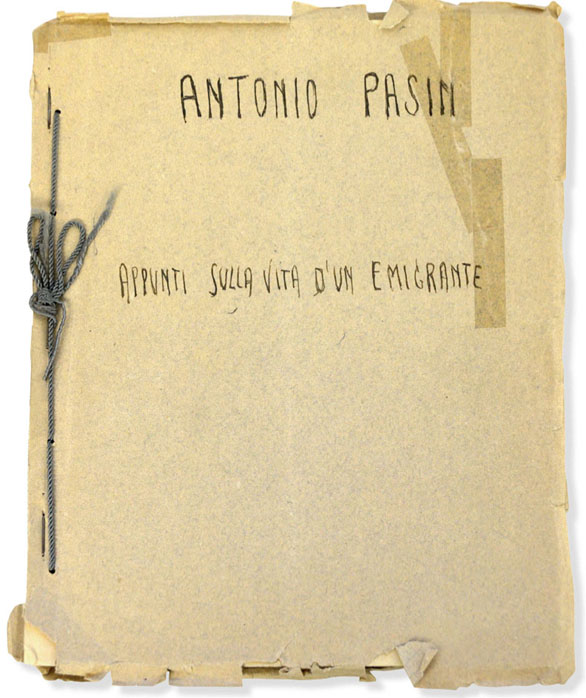

The cover of Antonio’s 1950 unpublished manuscript, titled Appunti Sulla Vita D’Un Emigrante (“Notes on the Life of an Immigrant”).