THE TOY INDUSTRY’S “LITTLE FORD”

Two workers load stamped-steel wagon bodies onto a conveyor belt.

Antonio’s methods for mass production of wagons were modeled after the automobile industry’s.

Antonio Pasin was always interested in the most modern ways of doing things, whether by using new materials, adopting the best practices for production used by factories in different industries, or constantly rethinking his designs to make them more durable, simpler, or sleeker. Rather than listen to his wood wagon competitors who accused his steel wagon of being dangerous—too hot in the summer and too cold in the winter—he continued to tinker and modernize every aspect of the wagon’s design.

One of the most important strategic decisions he would ever make was to adopt the same mass-production techniques used by the automobile industry, pioneered by Henry Ford while manufacturing the Ford Model T. Antonio invested in the same machines the automobile industry used to stamp metal, and reorganized his workers into assembly lines accompanied by the machines that were thoughtfully arranged to do the heavy lifting. It was revolutionary for a toy company to operate at this scale, and the results speak for themselves: Between 1931 and 1938, production doubled from 3,000 to 6,000 pieces a day, which amounted to no fewer than 1,500 shiny new wagons daily.

By the end of the decade, Radio Steel & Manufacturing Company was the world’s largest manufacturer of coaster wagons, and Antonio Pasin had come to be known as the “Little Ford” of the toy industry. So productive were Radio Steel’s manufacturing techniques that an economist from the University of Chicago came down to study Radio Flyer’s production, convinced that the company could not still be profitable while selling the wagons at such an affordable price.

Most important, Antonio had kept his promise. Using discounted materials and efficient production techniques not only saved the company, but allowed it to maintain its prices without compromising on quality—no matter how bad the economy got. It is because of this trust that Radio Flyer really became an icon of American culture. Besides surviving as a company and offering a standard line of products that epitomized quality and reliability, the Radio Flyer identity had been cemented by the trials of one of the toughest decades in America’s history. The little red wagon became symbolic of the same resilience and can-do spirit that defined a generation of children and families—it not only represented a child’s play and soaring imagination, but also encouraged hope for the future. And many of those children, who turned into parents and grandparents, would pass down their little red wagons in remembrance of simpler times.

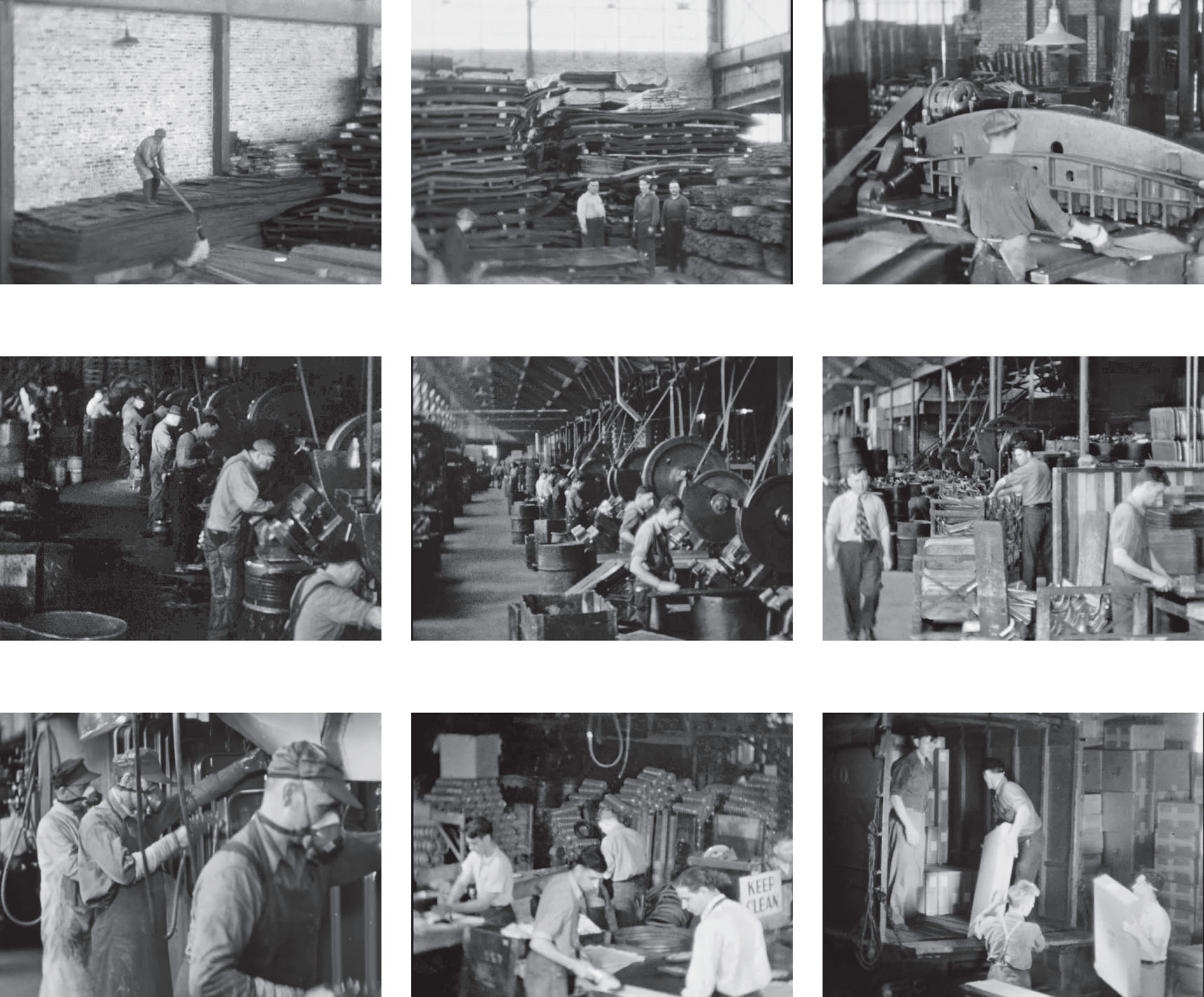

The Radio Steel & Manufacturing Company headquarters proudly housed one of the most modern toy factories in the world.

Workers paint wagon bodies red aided by a mechanized conveyor belt.

The tool room and machine shop where all original equipment was designed and made.

Stills from Antonio’s home movies featuring workers in a variety of daily jobs: welding, assembling, and inspecting the various parts of the wagon, painting the steel bodies, and sweeping and maintaining the factory. He used a 16mm camera to capture what was happening at the factory and brought the films back to Italy to show his family what he was doing in America.