A billboard that sat along the 101 Highway in the Bay Area in 2009 put it bluntly: “1,000,000 people overseas can do your job. What makes you so special?”1 While one million might be an exaggeration, what’s not an exaggeration is that lots of other people can and want to have your dream job. For anything desirable, there’s competition: a ticket to a championship game, the arm of an attractive man or woman, admission to a good college, and every solid professional opportunity.

Being better than the competition is basic to an entrepreneur’s survival. In every sector multiple companies compete over a single customer’s dollar. The world is loud and messy; customers don’t have time to parse minute differences. If a company’s product isn’t massively different from a competitor’s—as Do Something CEO Nancy Lublin says, unless it’s first, only, faster, better, or cheaper—it’s not going to command anyone’s attention. Good entrepreneurs build and brand products that are differentiated from the competition. They are able to finish the sentence, “Our customers buy from us and not that other company because …”

Zappos.com, the online shoe retailer founded in 1999, has a clear answer to that question: insanely good customer service. While other online shoe stores like shoebuy and onlineshoes.com offered 30-day return windows, Zappos made a name for itself by being the first to offer a 365-day return policy on everything they sold. While retailers like L.L. Bean and J. Crew expected customers to pick up the shipping costs each time they returned something from an online order, Zappos offered free shipping on all returns, no questions asked. And even when giants like The Gap mimicked the free shipping and free returns offer in their online shoe store, they buried a customer service phone number in small print at the bottom of the page. Zappos’ 1-800 number, on the other hand, is displayed “proudly,” in CEO Tony Hsieh’s words, on every single page of its website. Moreover, local employees working at corporate headquarters in Nevada answer every call. There are no scripts and no time limits on such calls—virtually unheard of in an age of quota-driven, outsourced customer service centers. Zappos massively differentiated itself from its competition by building a culture that is customer-centric in every way imaginable. This is what has made Zappos a trusted destination for millions of loyal online shoppers (and it’s also why it was acquired by Amazon for close to a billion dollars).

Yes, you are different from an online shoe store. But you are selling your brainpower, your skills, your energy. And you are doing so in the face of massive competition. Possible employers, partners, investors, and other people with power choose between you and someone who looks like you. When a desirable opportunity arises, many people with similar job titles and educational backgrounds will be considered. When sifting through applications for almost any job, employers and hiring managers are quickly overcome by the sameness.2 It’s a blur.

If you want to chart a course that differentiates you from other professionals in the marketplace, the first step is being able to complete the sentence, “A company hires me over other professionals because …” How are you first, only, faster, better, or cheaper than other people who want to do what you’re doing in the world? What are you offering that’s hard to come by? What are you offering that’s both rare and valuable?

You don’t need to be better or faster or cheaper than everyone. Companies, after all, don’t compete in every product category or offer every conceivable service. Zappos focuses on mainstream shoes and clothes. If it tried to offer over-the-top customer service on a range of high-end luxury products, it couldn’t be the place for quality shoes delivered with terrific service, because its focus would be diluted and its differentiation eroded. In life, there are multiple gold medals. If you try to be the best at everything and better than everyone (that is, if you believe success means ascending one global, mega leaderboard), you’ll be the best at nothing and better than no one. Instead, compete in local contests—local not just in terms of geography but also in terms of industry segment and skill set. In other words, don’t try to be the greatest marketing executive in the world; try to be the greatest marketing executive of small-to-midsize companies that compete in the health-care industry. Don’t just try to be the highest-paid hospitality operations person in the world; try to be a top-notch hospitality operations person in a way that’s aligned with your values so that you can sustain your work over the long run. What we explain in this chapter is how to determine the local niche in which you can develop a competitive advantage.

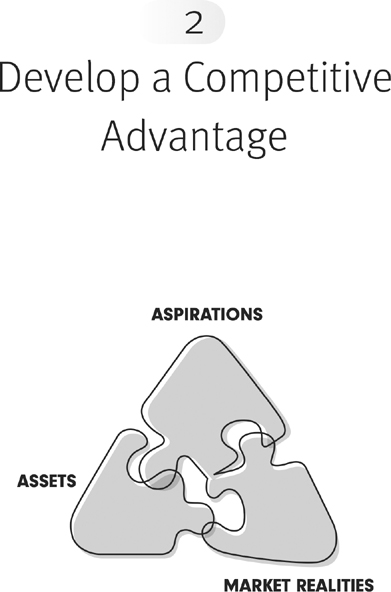

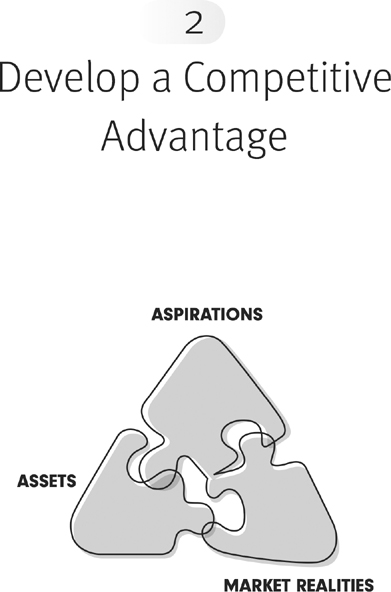

Competitive advantage underpins all career strategy. It helps answer the classic question, “What should I be doing with my life?” It helps you decide which opportunities to pursue. It guides you in how you should be investing in yourself. Because all of these things change, assessing and evaluating your competitive advantage is a lifelong process, not something you do once. And it’s done by understanding three dynamic puzzle pieces that fit together in different ways at different times.

Your competitive advantage is formed by the interplay of three different, ever-changing forces: your assets, your aspirations/values, and the market realities, i.e., the supply and demand for what you offer the marketplace relative to the competition. The best direction has you pursuing worthy aspirations, using your assets, while navigating the market realities. We’re not expecting you to already have a clear understanding of each of these pieces. As we show in the next chapter, the best way to learn about these things is by doing. But we want to introduce the concepts so you can begin to understand how they work, and how they inform the career decisions we’ll talk about in the rest of the book.

Assets are what you have right now. Before dreaming about the future or making plans, you need to articulate what you already have going for you—as entrepreneurs do. The most brilliant business idea is often the one that builds on the founders’ existing assets in the most brilliant way. There are reasons Larry Page and Sergey Brin started Google and Donald Trump started a real estate firm. Page and Brin were in a computer science doctoral program. Trump’s father was a wealthy real estate developer, and he had apprenticed in his father’s firm for five years. Their business goals emerged from their strengths, interests, and network of contacts.

You have two types of career assets to keep track of: soft and hard. Soft assets are things you can’t trade directly for money. They’re the intangible contributors to career success: the knowledge and information in your brain; professional connections and the trust you’ve built up with them; skills you’ve mastered; your reputation and personal brand; your strengths (things that come easily to you).

Hard assets are what you’d typically list on a balance sheet: the cash in your wallet; the stocks you own; physical possessions like your desk and laptop. These matter because when you have an economic cushion, you can more aggressively make moves that entail downside financial risk. For example, you could take six months off to learn the Ruby programming language with no pay—i.e., pick up a new skill. Or you could shift to a lower-paying but more stimulating job opportunity. During a career transition, someone who can go six to twelve months without earning money has different options—indeed, a significant advantage—over someone who can’t go more than a month or two without a paycheck.

Soft assets are more difficult to tally than cash in a bank account, but assuming your basic economic needs are taken care of, soft assets are ultimately more important. Dominating a professional project at work has little to do with how much dough you’ve socked away in a savings account; what matters are skills, connections, experiences. Because soft assets may be abstract, there’s a tendency for people to underestimate them when pondering career strategy. People list impressive-sounding-yet-vague statements like “I have two years of experience working at a marketing firm …” instead of specifying, explicitly and clearly, what they are able to do because of those two years of experience. One of the best ways to remember how rich you are in intangible wealth—that is, the value of your soft assets—is to go to a networking event and ask people about their professional problems or needs. You’ll be surprised how many times you have a helpful idea, know somebody relevant, or think to yourself, “I could solve that pretty easily.” Often it’s when you come in contact with challenges other people find hard but you find easy that you know you’re in possession of a valuable soft asset.3

Usually, however, single assets in isolation don’t have much value. A competitive edge emerges when you combine different skills, experiences, and connections. For example, Joi Ito, a friend and head of the MIT Media Lab, was born in Japan but raised in Michigan. In his mid-twenties he moved back to Japan and set up one of the first commercial Internet service providers there. He also kept developing connections in the United States, investing in Silicon Valley start-ups like Flickr and Twitter, establishing the Japanese subsidiary for the early American blogging company Six Apart, and more recently helping to establish LinkedIn Japan. Is Joi the only person with start-up experience who does angel investing in the Valley? No. Is he the only person with roots in both the United States and Japan? No. But combining these transpacific, bilingual, tech-industry assets gives him a competitive advantage over other investors and entrepreneurs.

Your asset mix is not fixed. You can strengthen it by investing in yourself—that’s what this book is about. So if you think you lack certain assets that would make you more competitive, don’t use it as an excuse. Start developing them. In the meantime, see how you can turn a weakness into a strength. For example, you may not see inexperience as an asset to highlight, but the flip side of inexperience tends to be energy, enthusiasm, and a willingness to work and hustle in order to learn.

Aspirations and values are the second consideration. Aspirations include your deepest wishes, ideas, goals, and vision of the future, regardless of the state of the external world or your existing asset mix. This piece of the puzzle includes your core values, or what’s important to you in life, be it knowledge, autonomy, money, integrity, power, and so on. You may not be able to achieve all your aspirations or build a life that incorporates all your values. And they will certainly change over time. But you should at least orient yourself in the direction of a pole star, even if it changes.

Jack Dorsey is cofounder and executive chairman of Twitter and cofounder and CEO of Square, a mobile credit card payments start-up. He’s known in Silicon Valley as a product visionary who prizes design and who takes inspiration from sources as varied as Steve Jobs and the Golden Gate Bridge. Both his companies have grown to towering heights (and multibillion-dollar valuations) while keeping Jack’s values and priorities intact. Twitter is still minimalistic and clean; the Square device is still elegant. His aspiration to make complex things simple and his value of design are part of the reason his companies have been so successful: they clarify product priorities, ensure a consistent customer experience, and make it easier to recruit employees who are attracted to similar ideas. For a start-up, a compelling vision that acts as a pole star is a meaningful piece of a company’s competitive advantage. Google’s clarity of purpose to “organize the world’s information,” for example, has drawn some of the brightest engineering minds while at the same time been broad enough to allow adaptation and reinvention.

Aspirations and values are both important pieces of your career competitive advantage quite simply because when you’re doing work you care about, you are able to work harder and better. The person passionate about what he or she is doing will outwork and outlast the guy motivated solely by making money. It can be easy to forget this when heading the start-up of you. In an effort to scrappily improve on who you are today, you can lose track of who you aspire to be in the future. For example, if you’re currently an analyst at Morgan Stanley, the savviest way to leverage your existing assets may be to angle for a promotion within the firm. If the banking industry is in a slump, the savviest way to attend to the market realities may be to develop skills in a different but related industry, like accounting. But would these moves reflect what you really care about?

That said, and contrary to what many bestselling authors and motivational gurus would have you believe, there is not a “true self” deep within that you can uncover via introspection and that will point you in the right direction.4 Yes, your aspirations shape what you do. But your aspirations are themselves shaped by your actions and experiences. You remake yourself as you grow and as the world changes. Your identity doesn’t get found. It emerges.

Accept the uncertainty, especially early on. Ben, for example, knows he values intellectual stimulation and trying to change real people’s lives through entrepreneurship and writing—though in what specific ways, he’s still figuring out. Entrepreneur and writer Chris Yeh says his career mission is to “help interesting people do interesting things.” That may sound airy, but it has real meaning: interesting reinforces the kind of stimulation he’s looking for, and do means “do,” not “think about.” Later in your career, you may have more specific, thought-out aspirations. These are not unlike a start-up’s mission statement. My pole star is to design and build human ecosystems using entrepreneurship, technology, and finance. I build networks of people using entrepreneurship, finance, and technology as enablers. Whatever your values and aspirations, know that they will evolve over time.

The realities of the world you live in is the final piece of the puzzle. Smart entrepreneurs know a product won’t make money if customers don’t want or need it, regardless of how slick its form and function (think of the Segway). Likewise, your skills, experiences, and other soft assets—no matter how special you think they are—won’t give you an edge unless they meet the needs of a paying market. If Joi were bilingual in an obscure African dialect as opposed to the language of the world’s third-largest economy (Japan), it wouldn’t contribute to a compelling advantage for working with technology companies. And keep in mind that the “market” is not an abstract thing. It consists of the people who make decisions that affect you and whose needs you must serve: your boss, your coworkers, your clients, your direct reports, and others. How badly do they need what you have to offer, and if they need it, do you offer value that’s better than the competition?

It’s often said that entrepreneurs are dreamers. True. But good entrepreneurs are also firmly grounded in what’s available and possible right now. Specifically, entrepreneurs spend vast amounts of energy trying to figure out what customers will pay for. Because ultimately, the success of all businesses depends on customers willing to sign on the line that is dotted. In turn, the success of all professionals—the start-up of you—depends on employers and clients and partners choosing to buy your time.

In 1985, when Howard Schultz (current CEO of Starbucks) was preparing to launch coffee bars in America modeled after those already in Italy, he and his partners didn’t just launch the stores on a whim. They first did everything in their power to understand the dynamics of the market they were entering. They visited five hundred espresso bars in Milan and Verona to learn as much as they possibly could. How did the Italians design their cafés? What were the local coffee-drinking habits? How did the baristas serve coffee? What did the menus look like? They scribbled observations in notebooks. They videotaped the stores in action.5 This kind of market research is not a one-time thing entrepreneurs do when a start-up first launches, either. David Neeleman founded his own airline, JetBlue Airways, and served as CEO for the first seven years. During that time he flew his own airline at least once a week, worked the cabin, and blogged about his experience: “Each week I fly on JetBlue flights and talk to customers so I can find out how we can improve our airline,” he wrote.6

Schultz and Neeleman had tremendous vision when they founded their start-ups. Yet from day one they focused on the needs of their customers and stakeholders. For all their smarts and vision, they knew well what VC and friend Marc Andreessen likes to say: Markets that don’t exist don’t care how smart you are. Similarly, it doesn’t matter how hard you’ve worked or how passionate you are about an aspiration: If someone won’t pay you for your services in the career marketplace, it’s going to be a very hard slog. You aren’t entitled to anything.

Studying the market realities doesn’t have to be a limiting, negative exercise. There are always industries, places, people, and companies with momentum. Put yourself in a position to ride these waves. The Chinese economy, the politician Cory Booker, environmentally friendly consumer products: each is a big wave. Being in a position to ride them—making the market realities work for you as opposed to against you—is key to achieving breakout professional success.

A good career plan accounts for the interplay of the three pieces—your assets, aspirations, and the market realities. The pieces need to fit together. Developing a key skill, for example, doesn’t automatically give you a competitive edge. Just because you’re good at something (assets) that you’re really passionate about (aspirations) doesn’t necessarily mean someone will pay you to do it (market realities). After all, what if someone else can do the same thing for lower pay or do it more reliably? Or what if there’s no demand for the skill to begin with? Not much of a competitive advantage. Following your passions also doesn’t automatically lead to career flourishing. What if you’re passionate but not competent, relative to others? Finally, being a slave to market realities isn’t sustainable. A shortage of nurses in hospitals—meaning there’s demand for credentialed nurses—doesn’t mean you should get on the nursing track. No matter what the demand, you’re not going to be most competitive unless your own passions and strengths are in play.

So evaluate each piece of the puzzle in the context of the others. And do so regularly: the pieces of the puzzle change in shape and size over time. The way they fit together shifts over time. Building a competitive advantage in the marketplace involves combining the three pieces at every career juncture.

For a long time, business was not among my assets, aspirations, or the reality that I perceived around me. I attended the progressive Putney School in Vermont for high school, where I farmed maple syrup, drove oxen, and debated practical topics like epistemology (the nature of knowledge) with my teachers. In college and graduate school, I studied cognitive science, philosophy, and politics. I formed a conviction that I wanted to try to change the world for the better. Initially, my plan was to be an academic and public intellectual. At the time, I got bored easily (still do), which made me distractible and not great at making the trains run on time. Academia seemed like an environment that would keep me perpetually stimulated as I would think and write on the value of compassion, self-development, and the pursuit of wisdom. I would hopefully inspire others to implement these ideas to form a nobler society.

But graduate school, while stimulating, turned out to be grounded in a culture and incentive scheme that promoted hyperspecialization; I discovered that academics end up writing for a scholarly elite of typically about fifty people. It turned out there was not much support for academics who would attempt to spread ideas to the masses. So my aspiration to have a broad impact on potentially millions of people clashed with the market realities of academia.

I adapted my career orientation. My new aim was to try to promote the workings of a good society via entrepreneurship and technology, the details of which we discuss in the next chapter. When I adapted and first thought about going into industry, I conducted informal informational interviews with friends from college who worked at companies like NeXT. I called them to figure out which skills I’d have to learn (e.g., writing product requirement documents) and the connections I’d have to build (e.g., working relationships with engineers). During my first technology job at Apple, one of the things I had to learn was Adobe Photoshop, for creating product mock-ups. Locking myself in a room for a weekend and becoming a Photoshop ninja was not an endeavor I thought was important while studying philosophy. However, being able to use Photoshop was necessary to pursue a product development career and therefore I learned it in order to advance in the industry. Trade-offs are inevitable when you’re balancing different considerations such as the market realities of employment and your own natural interests.

Even as I have developed a career in the technology industry I have not relinquished my original aspirations. In fact, the issues of personal identity and community incentives that I researched in academia are relevant to my current entrepreneurial passion for the social Web, online networks, and marketplaces. My longstanding interests in these themes have helped me develop industry skills and differentiation around the creation of massive Internet platforms.

Recently, I made a career move to start doing venture investing at Greylock. Again, I built on my assets and pursued my aspirations in the local environment in which I found myself. My significant operating experience at scale differentiates me from other VCs with finance backgrounds or limited operational backgrounds. This gives me a meaningful advantage in how I can partner with entrepreneurs and help them succeed. And since I can work with entrepreneurs whose companies build and define massive human ecosystems, I can help improve society at large scale, which meets my aspirations as a public intellectual. The three pieces fit.

The most obvious way to improve your competitive advantage is to strengthen and diversify your asset mix—for example, learn new skills. That’s certainly smart. But it’s equally effective to place yourself in a market niche where your existing assets shine brighter than the competition’s. For example, top American college basketball players who aren’t good enough to play professionally Stateside frequently play in European leagues. Instead of changing their skills, they change their local environment. They know they have a competitive advantage in a market with lower-quality competition.

Especially in the start-up world, competition—or lack thereof—makes a big difference. LinkedIn, from the outset, struck a different path from its competitors. In 2003, when LinkedIn started, its competitors were largely enterprise focused. Enterprise networks tied a person’s profile and identity to a specific company and employer. Instead, LinkedIn placed the individual professional at the center of the system. LinkedIn’s founding belief was that all individuals should own and manage their identities. They should be able to connect with people from other companies to work more effectively in their current jobs and find strong opportunities when they change jobs. LinkedIn had the right philosophy. The large social networks like Friendster, MySpace, and now Facebook have massive popularity, but none truly serves the needs of professionals. LinkedIn continues to invest in features that appeal to professionals and skips features like photo sharing or games that don’t contribute to its competitive advantage. LinkedIn competes in the event where it can win the gold medal; it leads the space it has defined.

You can carve out a similar professional niche in the job market by making choices that make you different from the smart people around you. Matt Cohler, now a partner at Benchmark Capital, spent six years in his late twenties and early thirties being a lieutenant to CEOs at LinkedIn (me) and Facebook (Mark Zuckerberg). Most supertalented people want to be the front man; few play the consigliere role well. In other words, there’s less competition and significant opportunity to be an all-star right-hand man. Matt excelled at this role, building a portfolio of accomplishments and relationships along the way. This professional differentiation in the market set him up to achieve a long-standing goal, which was to become a partner at a top-tier VC firm.

The three puzzle pieces become actionable when part of a good plan. In the next chapter we’ll explore themes of planning, adapting, and doing.

• Update your profile on LinkedIn so that your summary statement articulates your competitive advantages. You should be able to fill in this sentence: “Because of my [skill/experience/strength], I can do [type of professional work] better than [specific types of other professionals in my industry].”

• How would other professionals you work with fill in the above sentence (i.e., describe your competitive advantage)? If there’s a gap, you either have a self-judgment problem, or a marketing problem.

• Identify three people who are striving toward aspirations similar to your own. Use them as benchmarks. What are their differentiators? How did they get to where they are? Bookmark their LinkedIn profiles, subscribe to their blogs and tweets. Track their professional evolution and take inspiration and insight from their journeys.

• Go on LinkedIn or Twitter, search for your employer and other companies you’re interested in, and “follow” each of them. This will make it easier to track the emergence of new opportunities and risks.

• Write down some of your key assets in the context of a market reality. BAD: I excel at public speaking. GOOD: I excel at public speaking on engineering topics, relative to how good most engineers are at public speaking.

• Review your calendar, journals, and old emails and get a sense for how you spent your last six Saturdays. What do you do when you have nothing urgent to do? How you spend your free time may reveal your true interests and aspirations; compare them to what you say your aspirations are.

• Think about how you’re currently adding value at work. If you stopped going to the office suddenly, what would not get done? What’s a day in the life of your company with you not there? That may be where you’re adding value. Think about the things people frequently compliment you on—those may be your strengths.

• Create a soft-asset investment plan that emphasizes learning about growth markets and growth opportunities. Maybe this means taking a trip to China, attending a conference on clean technology, or signing up for a software programming course. Email your plan to three trusted connections and ask them to hold you accountable. Budget money to pay for these things, if necessary.

Meet with three trusted connections and ask them what they see as your greatest strengths. If they had to come to you for help or advice on one topic, what would it be?