Even if you realize the fact that you are in permanent beta, even if you develop a competitive advantage, even if you adapt your career plans to changing conditions—even if you do these things but do so alone—you’ll fall short. World-class professionals build networks to help them navigate the world. No matter how brilliant your mind or strategy, if you’re playing a solo game, you’ll always lose out to a team. Athletes need coaches and trainers, child prodigies need parents and teachers, directors need producers and actors, politicians need donors and strategists, scientists need lab partners and mentors. Penn needed Teller. Ben needed Jerry. Steve Jobs needed Steve Wozniak. Indeed, teamwork is eminently on display in the start-up world. Very few start-ups are started by only one person. Everyone in the entrepreneurial community agrees that assembling a talented team is as important as it gets.

Venture capitalists invest in people as much as in ideas. VCs will frequently back stellar founders with a so-so idea over mediocre founders with a good idea, on the belief that smart and adaptable people will maneuver their way to something that works. (We described this with PayPal and Flickr earlier in the book.) Not only should the founders be talented, they should be committed to getting other talented people on board. The strength of the cofounders and early employees reflects the individual strength of the CEO; that’s why investors don’t evaluate the CEO in isolation from his or her team. Vinod Khosla, cofounder of Sun Microsystems and a Silicon Valley investor, says, “The team you build is the company you build.” Mark Zuckerberg says he spends half his time recruiting.

Just as entrepreneurs are always recruiting and building a team of stunning people, you want to always be investing in your professional network to grow the start-up that is your career. Quite simply, if you want to accelerate your career, you need the help and support of others. Of course, unlike company founders, you aren’t hiring a fleet of employees who report to you, nor do you report to a board of directors. What you are doing—what you should be doing—is establishing a diverse team of allies and advisors with whom you grow over time.

Relationships matter to your career no matter the organization or level of seniority because every job boils down to interacting with people. In fact, the word company is derived from the Latin cum and pane, which means “breaking bread together.”1 Yes, even if you’re a solo software coder, you’ll still have to work with other people at some point, if you want to create a product people will actually use. Amazon, Boeing, UNICEF, and Whole Foods—to pick a handful of companies—are very different organizations, but they are all, ultimately, people organizations. People develop the technologies, write the mission statements, and stand behind the corporate logos and abstractions.

People are the source of key resources, opportunities, information, and the like. For example, my long-term friendship with Peter Thiel, which started in college, is what connected me to PayPal. Without the relationship, Peter never would have called me with the life-changing opportunity. Likewise, without the alliance, I wouldn’t have referred Sean Parker and Mark Zuckerberg to Peter during Facebook’s initial financing. In alliances, resources and assistance flow both ways.

People also act as gatekeepers. Jeffrey Pfeffer, professor of organizational behavior at Stanford, has marshaled evidence that shows that when it comes to getting promoted in your job, strong relationships and being on good terms with your boss can matter more than competence. This is not nefarious nepotism or politics (though unfortunately sometimes it’s that). There’s a good reason: a slightly less-competent person who gets along with others and contributes on a team can be better for the company than somebody who’s 100 percent competent but isn’t a team player.

Finally, relationships matter because the people you spend time with shape who you are and who you become. Behavior and beliefs are contagious: you easily “catch” the emotional state of your friends, imitate their actions, and absorb their values as your own.2 If your friends are the types of people who get stuff done, chances are you’ll be that way, too. The fastest way to change yourself is to hang out with people who are already the way you want to be.

Despite the fact that nothing important in life is done alone, we live in a hero-obsessed culture. If you survey the population on how a company of note like General Electric achieved its behemoth status, you’ll probably hear about Jack Welch, but not a peep about the team he built around him. And if you ask about the career of a person like Jack Welch, you’ll hear he got to the top of the totem pole because of things like hard work, intelligence, and creativity.

Typically, all kinds of individual attributes pepper explanations of a person’s success. Books that promise to improve your life are shelved under “self-help.” Seminars that promise to teach you how to be successful are considered personal development. Business schools rarely teach relationship-building skills. It’s all about me, me, me, me. Why do we rarely talk about the friends, allies, and colleagues who make us who we are?

In part it’s because the idea of a self-made man makes for a good story, and stories are how we process a messy, complex world. Good stories have a beginning, middle, and end; drama; clear causation; a hero and a villain. It’s easier to tell stories that neglect the surrounding cast. Superman and His Ten Allies doesn’t quite roll off the tongue as easily as Superman. We’ve been telling and retelling stories like these for centuries. Benjamin Franklin himself “artfully constructed his Autobiography as dazzling lessons in self-making.”3 Americans are particularly eager to embrace the self-made-man story because we are a country that has long celebrated the ideal of a guns-blazing John Wayne and the rugged individualism he stood for.

But tidy narratives tend to be misleading. In actuality, Franklin’s networks and relationships were a huge part of his life, and played a huge part in his success. Indeed, if you study the life of any notable person, you’ll find that the main character operates within a web of support. As tempting as it is to believe that we are the sole heroes of our own stories, we are enmeshed in cities, companies, fraternities, families, society at large—collections of people who shape us, help us, and yes, sometimes even hurt us. It is impossible to dissociate an individual from the environment of which he is a part. No story of achievement should ever be removed from its broader social context.

The self-made man may be a myth, but the old saw “There is no I in team” is wrong, too. There is an I in team. A team is made up of individuals with different strengths and abilities. Michael Jordan needed his team, but no one would dispute that he was more crucial to the success of the Chicago Bulls than his teammates. And one bad apple on an otherwise top-notch team can spoil the whole bunch. Research shows that a team in the business world will tend to perform at the level of the worst individual team member.4 Your individual talent and hard work may not be sufficient for success, but it’s absolutely necessary.

The nuanced version of the story of success is that both the individual and team matter. “I” vs. “We” is a false choice. It’s both. Your career success depends on both your individual capabilities and your network’s ability to magnify them. Think of it as IWe. An individual’s power is raised exponentially with the help of a team (a network). But just as zero to the one hundredth power is still zero, there’s no team without the individual.

This book is titled The Start-up of You. Really, the “you” is at once singular and plural.

“Relationship” can mean many things. It can be long distance or proximate, project only or long term, emotionally close or purely professional. There are bosses, coworkers, colleagues, and subordinates. There are friends, neighbors, family members, and long-lost acquaintances. There are people you relate to out of love, out of friendship, out of respect, and out of necessity. There are people you work with based on a detailed contract that legally specifies roles and responsibilities; there are people you work with where nothing is written down. The universality of the word relationship makes sense: the essence of how human beings relate to one another transcends situational differences.

That said, there are key differences in how relationships function based on the context. There are people you know solely in a personal context. These include close personal friends and family. These are the people you call on a Saturday night, but not on a busy Monday morning at work. These are your childhood, high school, or college friends who may be dear to you but are not necessarily on an even remotely similar career trajectory. These are the people with whom a shared spirituality and alignment of core values may matter. Online, you connect with these friends and family on Facebook. You share photos of last night’s party and play CityVille or Texas Hold’Em. Your Facebook profile picture might be kooky, and whether you are single or in a relationship is a point of interest for all.

Then there are those you know solely in a professional context. These include colleagues, industry acquaintances, customers, allies, business advisors, and service providers like your accountant or lawyer. You email these folks from your work address, and maybe not your personal Yahoo or Gmail account. Shared business goals and professional interests bring you together. Online, LinkedIn is where you connect with these trusted colleagues and valued acquaintances whom you recommend for jobs, collaborate with on professional projects, and tap for industry advice. It’s where you share detailed information about your skill sets and work experience. Your head shot is professional. No one cares who you are or are not dating on LinkedIn. While most people have a small circle of close friends, they maintain a large circle of these valued acquaintances and colleagues.

Generally, you know people primarily in a personal or a professional context. The simple reason is etiquette and expectations. It’s awkward if a coworker confesses marital infidelity while standing around the proverbial water cooler. (Cue a scene from the TV show The Office …) And your idea of a fun weekend might not involve playing in a sandbox with your coworker’s kids. The more important reason why personal and professional are separate relates to conflict of loyalties. For example, suppose a coworker you consider a personal friend is screwing up on a big work project. If you don’t speak up, you will be letting down other team members and your company as a whole, therefore hurting the project and your professional reputation at the same time. If you do speak up, your friend may resent you. Or suppose a personal friend asks you to be a reference on a prestigious job application, but you don’t think he’s truly qualified. It can strain the friendship. For these reasons, it can be tricky to ask close personal friends for career help because you’re asking them to negotiate dueling loyalties: their duties as a professional and their duties as a friend.

Now, it’s good to be friends with someone you work with. It’s more fun. You may invite your coworker to your wedding. You may go winetasting with your boss and direct report over the weekend. You may link with some people on both Facebook and LinkedIn. But even in these cases, the vast majority of the time there will be limits to how much the friendship can flourish. And context will continue to govern etiquette and expectations. You say and do different things when at a bar on a Saturday night than when in the office on a Wednesday afternoon, even if you’re with the exact same friends.

This chapter focuses on relationships that make you a more competitive business-of-one in a professional context. In other words, this is about professional relationships, and those personal friendships that also function in a professional context.

Many people are turned off by the topic of networking. They think it feels slimy, inauthentic. Go figure. Picture the consummate networker: the high-energy fast talker who collects as many business cards as he can, attends networking mixers in the evenings, sports slicked-back hair. Or the overambitious kid in your graduating class from college who frantically emails alumni, goes to cocktail parties with the board of trustees to schmooze, and adds anyone he’s ever met as a friend on online social networks. These people are drunk on networking Kool-Aid and await a potential nasty social and professional hangover. Luckily, building and strengthening your network doesn’t have to be like this.

Old-school “networkers” are transactional. They pursue relationships thinking only about what other people can do for them. And they’ll only network with people when they need something, like a job or new clients. Relationship builders, on the other hand, try to help other people first. They don’t keep score. They’re aware that many good deeds get reciprocated, but they’re not calculated about it. And they think about their relationships all the time, not just when they need something.

Networkers think it’s important to have a really big address book. This emphasis on quantity means they perhaps unknowingly form mostly weak relationships. Relationship builders prioritize high-quality relationships over a large number of connections.

Networkers focus on tactical ways to meet new people. They think about how to dominate a cocktail party or how to cold-call an important person in their field. Relationship builders start by understanding how their existing relationships constitute a social network, and they meet new people through people they already know.

True relationship building in the professional world is like dating. When you’re deciding whether or not to build a professional relationship with someone, there are many considerations: whether you like him or her; the capacity for the person to help you build your assets, reach your aspirations, and position you well competitively, and for you to help back in all the same ways; whether the person is adaptable and could help you adapt your career plan as necessary. And, like with dating, you should always have a long-term perspective.

Building a genuine relationship with another person depends on (at least) two things. The first is seeing the world from the other person’s perspective. No one knows this better than the skilled entrepreneur. Entrepreneurs succeed when they make stuff people will pay money for, which means understanding what’s going on in the heads of customers. Discovering what people want, in the words of start-up investor Paul Graham, “deals with the most difficult problem in human experience: how to see things from other people’s point of view, instead of thinking only of yourself.”5 Likewise, in relationships, it’s only when you truly put yourself in the other person’s shoes that you begin to develop an honest connection. This is tough. Whereas entrepreneurs have some ways of measuring how well they understand their customers by ultimately watching sales rise and fall, in day-to-day social life there’s no such immediate feedback. Compounding that challenge is the fact that the basic way we perceive and process the external world makes us feel like everything revolves around us. The late writer David Foster Wallace once noted this literal truth: “There is no experience you have had that you are not the absolute center of. The world as you experience it is there in front of you or behind you, to the left or right of you, on your TV or your monitor.”6

The second requirement is thinking about how you can help and collaborate with the other person rather than thinking about what you can get from him or her. When you come into contact with a successful person it’s natural to immediately think, “What can this person do for me?” If you were to have a chance meeting with Tony Blair, we can’t blame you for thinking about how you could get your photo taken with him. If you were to share a cab ride with a person of unusual wealth, it’s natural to think about trying to convince her to donate or invest in one of your causes. We’re not suggesting you be so saintly that a self-interested thought never crosses your mind. What we’re saying is you should let go of those easy thoughts and think about how you can help first. (And only later think about what help you can ask for in return.) A study on negotiation found that a key difference between skilled negotiators and average negotiators was the time spent searching for shared interests, asking questions of the other person, and forging common ground. The effective negotiators spent more time doing these things—thinking about ways the other person would truly benefit as opposed to just trying to drive a hard bargain out of pure self-interest.7 Do the same. Start with a friendly gesture toward the other person and genuinely mean it. (Later in the chapter we’ll show exactly how to help.)

Dale Carnegie’s classic book on relationships, despite all its wisdom, is unfortunately titled How to Win Friends and Influence People. This makes Carnegie widely misunderstood. You don’t “win” a friend. A friend is not an asset you own; it’s a shared relationship. A friend is an ally, a collaborator. Think of it like ballroom dancing. You don’t control the other person’s feet. Your task is to move in unison, perhaps gently guiding or following. There’s a deep sense of mutuality. Trying to win/acquire friends as if they were objects undermines the endeavor altogether.

Now, few would cop to charges that they are trying to “acquire” relationships in this manner. Yet, their actions and behaviors indicate otherwise, and their relationships suffer as a result. Sometimes they are giving off a bad impression by trying too hard to seem genuine and caring. When you can tell someone is attempting sincerity it leaves you cold. It is like the feeling you have when someone says your first name all the time in conversation and you know he’s been reading Carnegie. Or the feeling you get after reading networking books that stress being “authentic” but in the process make networking seem like a game that serves one’s crass individual ambition. Novelist Jonathan Franzen gets it right when he says inauthentic people are obsessed with authenticity. Unless the process of bonding and allying with others comes off as effortlessly as tying your shoes, which is to say, unless allying and helping really is what you want to be doing, the collaborative mind-set will fail, and so, ultimately, will the relationship.

In a sentence, as you meet your friends and new people, shift from asking yourself the very natural question of “What’s in it for me?” and ask instead, “What’s in it for us?” All follows from that.

If it’s not the sliminess of networking that turns some people away from the topic, it’s the presumption that building relationships in a professional context is like flossing: you’re told it is important, but it’s no fun. When you see relationship building as a chore, you’re more likely to go through the motions, be transactional (check the box on your to-do list), and acquire phony relationships as a result. This will make you ever more cynical, which results in even more phoniness. A vicious loop. It doesn’t have to be this way.

Think about some of your happiest memories. Were you alone? Or were you surrounded by friends or family? Think about some of your most adventurous, stimulating experiences. Were you alone, or with others? Building relationships should be fun. That’s how we think about it. Ben and I love the complexity of human interactions. We get excited at the prospect of working with others—it enlarges the sense of what’s possible and expands the box in which we think. (In fact, that’s why this book is the result of a collaboration.) We’re not suggesting you have to be an extrovert or life of the party. We just think it’s possible to appreciate the mystery of another person’s life experience. Building relationships is the thrilling if delicate quest to at once understand another person and allow that person to understand you.

This chapter is not about how to work a room or how to follow up after getting someone’s business card. We’re not going to tell you how to cold-call. That’s because the best way to engage new people is via the people you already know. According to the National Health and Social Life Survey, 70 percent of Americans meet their spouse through someone they know, while only 30 percent meet after a self-introduction.8 In a professional context, we would guess the numbers are even stronger in favor of introductions from existing connections.

So if you want to build a strong network that will help you move ahead in your career, it’s vital to first take stock of the connections you already have. And not just because your existing connections will introduce you to new ones. Your network is influencing you as we speak, changing how you think and act, and opening and closing certain career doors—sometimes without your even knowing it.

There are various types of relationships in personal and professional contexts, from intimate friends and family to polite coworker contacts to medium-strength trust connections. Each type of relationship is different. We’re going to focus on two types of relationships that matter in a professional context.

The first is professional allies. Who would be in your corner in a conflict or when you come under stress? Whom do you invite to dinner to brainstorm career options? Whom do you trust and proactively try to work with if you can? From whom do you solicit feedback on key projects? Whom do you review life goals and plans with? These are your allies. Many people can maintain at most eight to ten strong professional alliances at any given point in time.

The second type of relationship we’ll cover is weaker ties and acquaintances. With whom are you friendly but not full-on friends? With whom do you email occasionally? Of whom can you ask a lightweight professional favor? Can you recall a conversation with this person from a couple years ago? There’s quite a bit of variance in how many of these weak ties you can maintain; you may be able to maintain a maximum of a couple hundred or a couple thousand depending on your personality, your line of work, and the nature of your relationships.

In 1978 twenty-year-old Mary Sue Milliken graduated from culinary school in Chicago. Despite having no real-world experience, she was determined to get a job at the best restaurant in town—the legendary Le Perroquet. After a couple weeks of lobbying, she was finally hired to peel shallots full-time. Around the same time, Susan Feniger had also just graduated from culinary school, her sights set equally high. So she moved from New York to Chicago, and months later was cleaning vegetables and steaming broccoli in the kitchen at Le Perroquet. They were the only women working in the kitchen. They were also possibly the most passionate about food—every morning they showed up to work two and a half hours before their already long and grueling shift began. They developed a friendship, but after a year or so they each wanted new professional challenges, and their paths diverged. Feniger left for Los Angeles to work at the first U.S. restaurant of the then unknown Austrian chef Wolfgang Puck. Milliken stayed in Chicago and tried to start a café of her own. When the café didn’t work out, Milliken decided to improve her résumé with some experience working at restaurants in France. Though they hadn’t spoken in some time, she was moved to call Feniger to say hello and pass on the news that she was soon flying across the Atlantic. Feniger’s reply came as a shock: she was about to do the same. By coincidence, they were each starting new jobs in France the very next week.

Over meals at French bistros and weekend trips to small French towns, Milliken and Feniger reconnected and their relationship grew stronger, on both a personal and professional level. They dreamed of one day never having to work for someone else and perhaps even opening a restaurant of their own. When their stay in France drew to a close, they shook hands and promised each other they would work together at some point in their lives. Alas, it was not to be—at least not yet. Milliken eventually returned to Chicago and Feniger went back to Los Angeles, each picking up jobs at local restaurants.

In the months that followed, Feniger didn’t let either of them forget about their pact. She urged Milliken to move to Los Angeles so they could fulfill their vision. Milliken finally did, and they launched their first venture together: City Café, a cozy café in the eastern part of the city. The two of them manned the kitchen, and a dishwasher-cum-busboy handled the dishes. Due to the limited space, they set up their grill in the parking lot behind the restaurant. It was a makeshift operation, but by its third year, lines of hungry patrons were stretching around the block. Their next restaurant was bigger and better. They called it Ciudad and specialized in Latin American cuisine. It opened to critical acclaim. The media started showing interest in this chatty, charismatic duo. The story of their years-long alliance and simultaneous ascent from the kitchen to restaurant owners and chefs was compelling, and the popularity of their restaurants in Los Angeles (and Las Vegas) spoke for itself. The Food Network gave them a TV show called Too Hot Tamales. Publishers courted them to write cookbooks. Three decades after meeting in that first kitchen washing food and cleaning plates, Milliken and Feniger have cemented their place as leading authorities on Latin American cuisine in the United States.

Reflecting on why their alliance has thrived, Milliken points to their complementary strengths and interests: “[F]rom the first time we got in the kitchen together, we gravitated to different sides. [Feniger] loves chaos—when there’s a huge mess, and the waiters are screaming, and the cooks don’t know what to do, and everybody’s in a big horrible kind of catastrophe mode. That’s when [Feniger] is the happiest, in the middle of that. I’m about precision and planning and not being caught in that.”

Today, the alliance is evolving again. Feniger recently launched her first restaurant on her own, without Milliken as business partner. In some sense, this makes Feniger’s solo restaurant a competitor to their joint operations. The two of them insist they are still strong allies. And they are. Since allies often play in the same space, sometimes they end up competing against each other. “Competitive ally” may seem like an oxymoron. But you know it’s a strong alliance if you are able to navigate the occasional tricky situation with mutual respect intact.*

What are the general characteristics that make their relationship an alliance and that define your own? First, an ally is someone you consult regularly for advice. You trust his or her judgment. Second, you proactively share and collaborate on opportunities together. You keep your antennae especially attuned to an ally’s interests, and when it makes sense to pursue something jointly, you do so. Third, you talk up an ally to other friends. You promote his or her brand. When an ally comes into conflict, you defend him, and stand up for his reputation. And he does the same for you when times get tough. There’s no such thing as a fair-weather alliance; if the relationship isn’t load-bearing under stress, it’s not an alliance. Finally, you are explicit about your bond: “Hey, we’re allies, right? How can we best help each other?”

Ron Howard and Brian Grazer, top producers and directors in Hollywood, have a legendary alliance and partnership. The essence of their alliance was well summed up by Howard: “In a business that is so crazy, to actually know that there is somebody who is really smart, who you care about, who has your interests, and who is rowing in the same direction, is something of immense value.” That’s an ally.

I first met Mark Pincus while at PayPal in 2002. I was giving him advice on a start-up he was working on, as my PayPal experiences were relevant. From our first conversation, I felt inspired by Mark’s wild creativity and how at times he seems to bounce off the walls with energy. I’m more restrained in comparison, preferring to fit ideas into strategic frameworks instead of unleashing them fire-hose-style. Our different styles make conversation fun. But it’s our similar interests and vision that have made our collaborations so successful. We invested in Friendster together in 2002, at the dawn of social networking. In 2003 the two of us bought the Six Degrees patent, which covers some of the foundational technology of social networking. Mark then started his own social network, Tribe; I started LinkedIn. When Peter Thiel and I were set to put the first money into Facebook in 2004, I suggested that Mark take half of my investment allocation. As a matter of course, I wanted to involve Mark in any opportunity that seemed intriguing, especially one that played to his social networking background—it’s what you do in an alliance. In 2007, Mark called me to talk about his idea for Zynga, the social gaming company he cofounded and now leads. I knew almost immediately that I wanted to invest and join the board, which I did. Both of us thought Zynga and Facebook would be very strong companies, but no one could have predicted the astronomical heights of success. With an ally, you don’t keep score, you just try to invest in the alliance as much as possible. What sustains all this collaboration? We are both driven by a passion for the Internet industry, especially the social networking space. We complement each other. We like each other as friends. We’ve known each other for a while—it was several years before we thought of each other as allies. And there’s another seemingly insignificant reason, but it’s important and worth noting: we both live in the San Francisco Bay Area. Physical proximity is actually one of the best predictors of the strength of a relationship, many studies show.

Exciting as the business outcomes have been for Mark and me, an alliance can be enriching even if lots of money is not at stake. Early in your career, allies help with self-discovery, building your network, and planning for the future. Ben’s alliance with entrepreneurs Ramit Sethi and Chris Yeh is a trust bank that’s primarily about deepening their shared understanding of the world. One twenty-first-century-only quality of their alliance is how they engage with one another online. Using the bookmarking service Delicious, Ramit, Chris, and Ben have been following and reading one another’s favorite articles, videos, blog posts, and other Web pages for almost five years. Seeing what someone’s reading is like seeing the first derivative of their thinking. Thousands of bookmarks, tweets, and blog posts later, each of them possesses an intricate understanding of what’s on the others’ minds on a daily basis. This means every phone call and meeting feels like it’s picking up the conversation right where they left off—a few minutes ago. It comes as no surprise that when brains are so connected, trust, friendship, and fruitful business collaborations result.

An alliance is always an exchange, but not a transactional one. A transactional relationship is when your accountant files your tax returns and in exchange you pay him for his time. An alliance is when a coworker needs last-minute help on Sunday night preparing for a Monday morning presentation, and even though you’re busy, you agree to go over to his house and help.

These “volleys of communication and cooperation” build trust. Trust, writes David Brooks, is “habitual reciprocity that becomes coated by emotion. It grows when two people … slowly learn they can rely upon each other. Soon members of a trusting relationship become willing to not only cooperate with each other but sacrifice for each other.”9

You cooperate and sacrifice because you want to help a friend in need but also because you figure you’ll be able to call on him in the future when you are the one in a bind. This isn’t being selfish, it’s being human. Social animals do good deeds for one another in part because the deeds will be reciprocated at some point in time. With trusted professional allies, the reciprocation isn’t immediate—i.e., you don’t turn around the next day and say, “Hey, I helped you with your presentation, now I want something back.” Ideally, the notion of an exchange dissolves into the reality that you have intermingled fates. In other words, as the score keeping becomes less and less formal and as the expectation for reciprocal exchange stretches over a longer and longer period of time, a relationship goes from being an exchange partnership to being a true alliance.*

Allies, by the nature of the bond, are few in number. There are many more looser connections and acquaintances who also play a role in your professional life. These are folks you meet at conferences, old classmates, coworkers in other divisions, or just interesting people with interesting ideas who you come upon in day-to-day life. Sociologists refer to these contacts as “weak ties”: people with whom you have spent low amounts of low-intensity time (for example, someone you might only see once or twice a year at a conference, or only know online and not in person) but with whom you’re still friendly.

Weak ties in a career context were formally researched in 1973, when sociologist Mark Granovetter asked a random sample of Boston professionals who had just switched jobs how they found their new job. Of those who said they found their job through a contact, Granovetter then asked how frequently they saw the contact. He asked participants to mark whether they saw the person often (twice a week), occasionally (more than once a year but less than twice a week), or rarely (once a year or less).10 About 16 percent of the recipients said they found their job through a contact they saw often. The rest found their job through a contact they saw occasionally (55 percent) or rarely (27 percent). In other words, the contacts who referred jobs were “weak ties.”11 He summed up his conclusion in a paper appropriately called “The Strength of Weak Ties”: The friends you don’t know very well are the ones who refer winning jobs.

Granovetter accounts for this result by explaining that social cliques, which are groups of people who have something in common, often limit your exposure to wildly new experiences, opportunities, and information. Because people tend to hang out in cliques, your good friends are usually from the same industry, neighborhood, religious group, and the like. The stronger your tie with someone, the more likely they are to mirror you in various ways, and the more likely you are to want to introduce them to your other friends.12

From an emotional standpoint, this is great. It’s fun to do things in groups with people with whom you have a lot in common. But from an informational standpoint, Granovetter argues that this interconnectedness is limiting because the same information recycles through your local network of like-minded friends. If a close friend knows about a job opportunity, you probably already know about it. Strong ties usually introduce redundancy in knowledge and activities and friend sets.

In contrast, weak ties usually sit outside of the inner circle. You’re not necessarily going to introduce a looser connection to all of your other friends. Thus, there’s a greater likelihood a weak tie will be exposed to new information or a job opportunity. This is the crux of Granovetter’s argument: Weak ties can uniquely serve as bridges to other worlds and thus can pass on information or opportunities you have not heard about. We would stress that it’s not that weak ties per se find you jobs; it’s that weak ties are likely to be exposed to information or job listings you haven’t seen. Weak ties in and of themselves are not especially valuable; what is valuable is the breadth and reach of your network.

This complicating qualification has gotten lost ever since Malcolm Gladwell touted Granovetter’s study in his megabestseller The Tipping Point. Weak ties are indeed important, but they are only valuable so long as they offer new information and opportunities. Not all weak ties do. A weak tie who works in your field and is exposed to the same people and information is not going to be the bridge that Granovetter talks about. And since information is today more accessible than ever before, the bridge described by Granovetter in the 1970s is less important now than it was then. If you wanted to stay abreast of what was happening in Brazil back then, your best and perhaps only bet was to maintain a connection with someone who lived in Brazil or traveled there frequently. Now, of course, there are thousands of media sources a click away that offer insight on what’s happening in distant lands. In the 1970s, if you wanted to get a job in another city, a friend in that city would have to see a job listing in the local newspaper for a local company, then snail-mail you the clipping. Today all jobs are posted online. It’s easier to come by information swirling about in other social scenes, even if you don’t have a weak tie yourself on the ground there. So weak ties are one way to achieve a wide-reaching network, but any relationship that bridges you to another world will do.*

Whichever way you introduce diversity and breadth, it’s especially important during career transitions. When you pivot to Plan B or Plan Z, you’ll want information about new opportunities. You’ll also want to know people in different niches or fields who will encourage your move. As Herminia Ibarra says in her book Working Identity, sometimes it’s the strong ties who know us best who may wish to be supportive of a transition but instead “tend to reinforce or even desperately try to preserve the old identities we are seeking to shed. Diversity and breadth in your network encourages flexibility to pivot.”13

Imagine you receive a digital camera with a built-in memory card for your birthday. You bring it on a six-month trip to Africa where you won’t have access to a computer—so all the photos you want to keep must fit on that one memory card. When you first arrive you snap photos freely, and maybe even record some short videos. But after a month or so, the memory card starts filling up. Now you’re forced to be more judicious in deciding how to use that storage. You might take fewer pictures. You might decide to reduce the quality/resolution of the photos you do take in order to fit more. You’ll probably cut back on videos. Still, inevitably, you’ll hit capacity, at which point if you wish to take new photos you’ll have to delete old ones. Just as a digital camera cannot store an infinite number of photos and videos, you cannot maintain an infinite number of relationships. Which is why, even if you are judicious about your choices, at some point you hit a limit, and any new relationship means sacrificing an old one.

The maximum number of relationships we can realistically manage—the number that can fit on the memory card, as it were—is described as Dunbar’s Number, after evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar. But maybe it shouldn’t be. In the early nineties, Dunbar studied the social connections within groups of monkeys and apes. He theorized that the maximum size of their overall social group was limited by the small size of their neocortex. It requires brainpower to socialize with other animals, so it follows that the smaller the primate’s brain, the less efficient it is at socializing, and the fewer other primates it can befriend. He then extrapolated that humans have an especially large neocortex and so should be able to more efficiently socialize with a great number of humans. Based on our neocortex size, Dunbar calculated that humans should be able to maintain relationships with no more than roughly 150 people at a time. To cross-check the theory, he studied anthropological field reports and other clues from villages and tribes in the hunter-gatherer era. Sure enough, he found the size of surviving tribes tended to be about 150. And when he observed modern human societies, he found that many businesses and military groups organize their people into cliques of about 150. To wit: Dunbar’s Number of 150.14

But Dunbar’s research is not exactly about the total number of people that any one person can know. The research focused on how many nonhuman primates (and humans, but only by extrapolation) can survive together in a tribe. Of course, group limits and the number of people you can know are closely related concepts, especially if you consider everyone in your life to be part of your social group. Yet most of us define our total social group more broadly than Dunbar did in his research. Survival in the modern world doesn’t depend on having direct, face-to-face contact with everyone in our social network/group, as it did for the tribes he studied.

Regardless of how you parse Dunbar’s research, what is definitely the case is that there is a limit to the number of relationships you can maintain, if for no other reason than the fact that we have only twenty-four hours in each day. But, contrary to popular understanding of Dunbar’s Number, there is not one blunt limit. There are different limits for each type of relationship. Think back to the digital camera. You can either take low-resolution photographs and store one hundred photos in total, or you can take high-resolution photographs and store forty. With relationships, while you can only have a few close buddies you see every day, you can stay in touch with many distant friends if you only email them once or twice a year.

But there’s a twist. While the number of close allies and weak ties you can keep up is limited, those aren’t your only connections. You can actually maintain a much broader social network that exceeds the size of the memory card. It’s by smartly leveraging this extended network that you fully experience the power of IWe.

Your allies, weak ties, and the other people you know right now are your first-degree connections. À la Dunbar, there are limits to the number of first-degree connections you can have at any one time. But your friends know people you don’t know. These friends of friends are your second-degree connections. And those friends of friends have friends of their own—those friends of friends of friends are your third-degree connections.

Social network theorists use degree-of-separation terminology to refer to individuals who sit within your social network. A network is a system of interconnected things, like the world’s airports or the Internet (a network of computers and servers). A social network is a set of people and the connections that link them. Everyone you interact with in a professional context comprises your professional social network.

Think of the times you’ve met someone and discovered you know people in common. The clerk at the local hardware store once hiked through Yosemite with your brother-in-law. Your new girlfriend is in the same bowling league as your boss. “It’s a small world,” we say after such realizations. It’s fun to make these unexpected connections. A busy city street can seem awash with strangers, so when we encounter a familiar face, we notice it.

But is the world actually that small? Psychologist Stanley Milgram and his student Jeffrey Travers found that it is. In fact, it’s smaller and more interconnected than the occasional surprising mutual acquaintance might suggest.15 In 1967 they conducted a famous study in which they asked a couple hundred people in Nebraska to mail a letter to someone they knew personally who might in turn know a target stockbroker in Massachusetts. Travers and Milgram tracked how long it took for the letter to pass hands and reach its destination. On average, it took six different stops before it showed up at the stockbroker’s home or office in Massachusetts. In other words, the original sender in Nebraska sat six degrees apart from the recipient in Massachusetts. It was this study that birthed the Six Degrees of Separation theory, and the credible idea that you share mutual acquaintances with complete strangers on the other side of the world.

In 2001, sociologist Duncan Watts, inspired by Milgram’s findings, led a more ambitious, rigorous study on a global scale.16 He recruited eighteen targets in thirteen countries. From an archival inspector in Estonia to a policeman in Western Australia to a professor in upstate New York, the targets were selected to be as diverse as possible. Then he signed up more than sixty thousand people from across the United States to participate in the test. They were to forward an email message to one of the eighteen targets, or to a friend who might know one of the targets. Amazingly, factoring in the emails that never made it to their destination, Watts found that Milgram had been right all along: the median distance that separated a participant from a target was between five and seven degrees.

It is a small world, after all. Small because it is so interconnected.

Milgram’s and Watts’s research shows planet Earth as one massive social network, with every human being connected to every other via no more than about six intermediary people. It’s neat to ponder being connected to billions of people through your friends, and the practical implications for the start-up of you are significant as well. Suppose you want to become a doctor and would like to meet a premier M.D. in your specific field of interest. You’ve heard that getting an introduction is the only way you’ll be able to meet her. The good news is that you know that you are at most only six degrees away from her. The bad news is that following Milgram’s or Watts’s procedure—asking one good friend to forward an email and hope that six or seven email forwards later the email will arrive at the target’s computer—is neither efficient nor reliable. Even if it does arrive, the introduction would be highly diluted. Saying you’re a friend of a friend of a friend of a friend of a friend of a friend doesn’t quite carry enough heft to open doors.

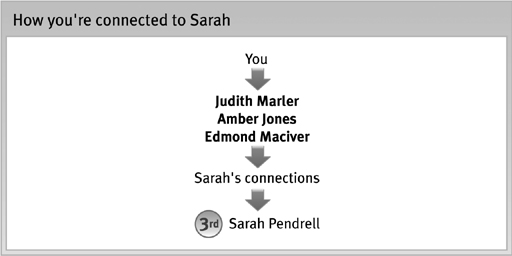

But if there were a master chart of the entire human social network, you could locate the shortest possible path from you to the doctor. Now, increasingly, there is. Online social networks are converting the abstract idea of worldwide interconnectedness into something tangible and searchable. Out of an estimated one billion professionals in the world, well over 100 million of them are on LinkedIn, with more than two new members joining every second. Now, you can search this network to find the connections and friends of connections who can introduce you to that all-star doctor with the fewest number of handoffs. You don’t need to randomly forward an email and hope it arrives at your destination after six twists and turns. For example, this screenshot from LinkedIn shows the intermediate hops from one user to Dr. Sarah Pendrell.

Here’s where the caveat to the Six Degrees of Separation theory comes in. Academically, the theory is correct, but when it comes to meeting people who can help you professionally, three degrees of separation is what matters. Three degrees is the magic number because when you’re introduced to a second- or third-degree connection, at least one person in an introduction chain personally knows the origin or target person. In this example: You—> Karen—> Jane—> Sarah. Karen and Jane are in the middle, and both of them know either You or Sarah—the two people who are trying to connect. That’s how trust is preserved. If one additional degree of separation is added, a person in the middle of the chain will know neither You nor Sarah, and thus have no stake in making sure the introduction goes smoothly. After all, why would a person bother to introduce a total stranger (even if that stranger is a friend of a friend of a friend) to another total stranger?

So, the extended network that’s available to you professionally doesn’t contain the roughly seven billion other humans on the planet who sit six degrees away. But it does contain all the people who sit two or three degrees away, because they are the people you can reach via an introduction. This is a large group. Suppose you have 40 friends, and assume that each friend has 35 other friends in turn, and each of those friends of friends has 45 unique friends of their own. If you do the math (40 × 35 × 45), that’s 54,000 people you can reach via an introduction.

Granted, some of your friends will know one another, so accounting for redundancy, the total number is a bit smaller. If you look at a LinkedIn user’s “Network Statistics” page, which shows the size of a member’s professional network to the third degree and accounts for any redundancy, you’ll see it’s still a big number (see chart on this page).

A person with 170 connections on LinkedIn is actually at the center of a professional network that’s more than two million people strong. Now you know why one of LinkedIn’s early marketing taglines was: YOUR NETWORK IS BIGGER THAN YOU THINK. It is!

And it’s more powerful than you may think, too. Frank Hannigan, a software entrepreneur in Ireland, raised more than $200,000 in funding for his company in eight days in 2010 by reaching out to his seven hundred first-degree connections on LinkedIn and pitching them on his business. Seventy percent of those who invested were among his first-degree connections; 30 percent were second-degree connections, that is, friends of his contacts who forwarded the initial message and brokered an introduction. This is the power of the extended network.

Now that you’ve found the best path to a top M.D.—or that ideal angel investor, or that hiring manager with the perfect job opening, or anyone else who can open doors for you—how do you actually reach that second- or third-degree connection?* The best (and sometimes only) way: via an introduction from someone you know who in turn knows the person you want to reach. When you reach out to someone via an introduction from a mutual friend, it’s like having a passport at the border—you can walk right through. The interaction is immediately endowed with trust.

I receive about fifty entrepreneur pitches by email every day. I have never funded a company directly from a cold solicitation and my guess is I never will. When an entrepreneur comes referred by introduction, someone I trust has already vetted that entrepreneur. Working within my trusted extended network allows me to move quickly when sifting through deals.

Anytime you want to meet a new person in your extended network, ask for an introduction. People know they should do this, but most don’t. It’s easier to cold-call. It can be awkward to ask a favor of a friend. Indeed, just because you know someone doesn’t mean they have to introduce you to one of their friends. But you do have to ask—directly and specifically—and you need to present a compelling reason why the introduction makes sense. “I’d love to meet Rebecca because she works in the technology industry.” Not good enough. “I’m interested in talking to Rebecca because my company is looking to partner with companies just like hers.” Better, as the introduction appears to benefit both parties. When you reach out to someone, be clear about how you intend to help the person to whom you’re being introduced—or at least how you’ll ensure it’s not a waste of that person’s time.

Figuring out how you can help the person you want to connect with—or at least figuring out the tightest point of mutual interest—does take some legwork. OkCupid, the free online dating site, analyzed more than five hundred thousand first messages between a man or a woman and a potential suitor. They found that those that garnered the highest response rates included phrases like “You mention …” or “I noticed that …” or “I’m curious what.…”17 In other words, phrases that showed that the person had carefully read the other’s profile. People do this in online dating, but when it comes to professional correspondence, for whatever reason, it doesn’t get done. People send out appallingly unresearched and generic requests. If you spend thirty minutes researching a person in your extended network (LinkedIn is a great place to start), and tailor your request for an introduction to something you’ve learned, your request will stand out. For example, “I noticed you spent a summer working at a German architecture firm. I once worked for an ad agency in Berlin and am thinking about returning—perhaps we could swap notes about business opportunities in the country?”

You can conceptualize and map your network all you want, but if you can’t effectively request and broker introductions, it adds up to a lot of nothing. Take it seriously. If you are not receiving or making at least one introduction a month, you are probably not fully engaging your extended professional network.

Several years ago, sociologist Brian Uzzi did a study of why certain Broadway musicals made between 1945 and 1989 were successful (like West Side Story or Bye Bye Birdie), and why others flopped.18 What did a winner have that the loser didn’t? The explanation he arrived at had to do with the social networks of the people behind the productions. For failed productions, one of two extremes was common. The first kind of failed production was collaborations between creative artists and producers who tended to all know each other from previous gigs. When there were mostly strong ties among those orchestrating the show, the production lacked the fresh, creative insights that come from diverse experience. On the opposite extreme, the other type of failed production was one in which none of the artists had experience working together. When the group was made up of mostly weak ties, teamwork and communication and group cohesion suffered. In contrast, the social networks of the people behind successful productions had a healthy balance: some of the people involved had preexisting relationships and some didn’t. There were some strong ties, some weak ties. There was some established trust among the producers, but also enough new blood in the system to generate new ideas. A key factor in the success of a musical, Uzzi concluded, is an optimal blend of cohesion and creativity (that is, strong ties and weak ties) within the social networks of the people behind the scenes.

The same dynamic is also at work in places far away from the Broadway lights. The Grameen Bank, founded by Nobel Prize winner Muhammad Yunus, is loaning small amounts of money to groups of people in the impoverished villages of rural Bangladesh. These are people who would never qualify for conventional bank loans as individuals. Yunus’s pioneering insight was that loaning to groups rather than individuals creates peer pressure within the group to pay back the loans, reducing the risk of default. But Grameen doesn’t loan money to just any group that walks in the door. The loan analyst looks for groups most likely to repay the loan, and one of the best predictors of that is the structure of the group’s social network. Sociologists Nicholas Christakis and James Fowler summarize the bank’s approach as follows: “Grameen Bank fosters strong ties within groups that optimize trust and then connects them via weaker ties to members of other groups to optimize their ability to find creative solutions when problems arise.”19 Strong connections optimize trust because there’s likely overlap in belief systems and communication styles. Weak connections help find creative solutions by introducing new information and resources from other social circles.

Think of your network of relationships in the same way: The best professional network is both narrow/deep (strong connections) and wide/shallow (bridge ties).

Only strong connections provide depth, of course, which is why these more intimate alliances are the most important kind of bond. But they can also be helpful for breadth in ways weak ties cannot. Your stronger connections are more likely to happily introduce you to new people—to your second- and third-degree connections. Weak connections, while valuable sources of new information, will not usually introduce you to other people unless they have a compelling transactional reason (i.e., unless it benefits them in some way). Again, Granovetter would point out the redundancy problem of strong ties—most of your good friends know one another and therefore anyone they’d introduce you to would be someone you either (a) already know or (b) wouldn’t obtain any new or interesting information from. Which is why you should relish opportunities to build trust connections with folks in different fields or social circles. Prize diversity, though don’t resolutely seek it out in a way that can come off as calculated. When you hit it off with someone who is meaningfully different from you, know that the relationship has the potential to be both genuinely enriching as well as a way to expand the breadth of information and creativity that flows through your network.

By now you should see why there’s a big difference between being the most connected person and being the best connected person.20 The value and strength of your network are not represented in the number of contacts in your address book. What matters are your alliances, the strength and diversity of your trust connections, the freshness of the information flowing through your network, the breadth of your weak ties, and the ease with which you can reach your second- or third-degree connections. There are, in short, several factors that contribute to a fulfilling, helpful professional network.

Your approach to your network should be unique to you. When you’re young and exploratory, many weaker connections in disparate fields may be especially valuable. When you’re midflight, perhaps you want to shore up alliances and make deep connections in certain niche areas. Whatever your priorities, nurture the network you’re building. Your professional life depends on your being smart and generous with the people you care about.

Relationships are living, breathing things. Feed, nurture, and care about them: they grow. Neglect them: they die. This goes for any type of relationship on any level of intimacy. The best way to strengthen a relationship is to jump-start the long-term process of give-and-take. Do something for another person. Help him or her. But how?

Here’s a good example. When Jack Dorsey was cofounding Square—the mobile payments company that turns any smartphone into a device that accepts the swipe of a credit card—he had loads of investor interest. For killer entrepreneurs with a killer idea, it’s actually the investors who compete for the privilege to invest. Digg and Milk founder Kevin Rose had seen a prototype of the Square device and immediately realized the potential for small businesses. When he asked Jack if there was room for another person to join the initial round of funding, Jack told him it was full—they didn’t need more investors. That was that. But Kevin still wanted to be helpful. He noticed that Square didn’t have a video demo on their website showing how the device worked. So he put together a hi-def video showing off the device and then showed the video to Jack just as an fyi. Impressed, Jack turned around and invited Kevin to invest in the “full” Series A round of financing. Kevin found a way to add value. He didn’t ask for anything in return—he just made the video and showed it to Jack. No strings attached. Not surprisingly, Jack appreciated the effort and returned the favor.

Helping someone out means acknowledging that you are capable of helping. Reject the misconception that if you’re less powerful, less wealthy, or less experienced, you have nothing to offer someone else. Everyone is capable of offering helpful support or constructive feedback. To be sure, you’ll be most helpful if you have the skills and experiences to help your allies. Pleasant friendships are nice, but the best-connected professionals are ones who can really help their allies. This is what makes a professional network and not simply a social one.

Next, figure out what kind of help is helpful. Imagine sitting down to lunch with an acquaintance you just met and opening the conversation by saying, “I’m looking for a job in New York City.” He puts down his fork, wipes the barbecue sauce off his face, looks you square in the eye, and replies, “I know the perfect job for you.” Is that helpful? Hardly. Since he likely has no idea what the perfect job means to you, a better response would have probed: “Tell me more about your skills, interests, and background.” Good intentions are never enough. To give helpful help you need to have a sense of your friend’s values and priorities so that your offer of help can be relevant and specific. What keeps him up at 2 a.m.? What are his talents? His interests? Asking “How can I help you?!” immediately after meeting someone is overeager. First you must know the person.

Finally, once you understand his needs, challenges, and desires, think about how you can offer him a small gift. We don’t mean an Amazon.com gift card or a box of cigars. We mean something—even something intangible—that costs you almost nothing yet still is valuable to the other person. Classic small gifts include relevant information and articles, introductions, and advice. A really expensive big gift is actually counterproductive—it can feel like a bribe. Inexpensive yet thoughtful is best.

When deciding what kind of gift to give, think about your unique experiences and skills. What might you have that the other person does not? For example, consider an extreme hypothetical. What kind of gift would be helpful to Bill Gates? Probably not introducing him to somebody—he can meet whomever he wants. Probably not sending an article you read in the media about the Gates Foundation—he was probably interviewed for it. Probably not by investing in one of his projects—he’s doing fine money-wise. Instead, think about little things. For example, if you’re in college, or have a good friend or sibling in college, you could send him information about some of the key cultural and technology-usage trends among the college set. Intel on what college students—the next generation—are thinking or doing is always of interest yet hard to get no matter how much money you have. What specific things do you know or have that the other person does not? The secret behind stellar small gifts is that it’s something you can uniquely provide.

Finally, if the best way to strengthen a relationship is to help the other person, the second best way is to let yourself be helped. As Ben Franklin recommended, “If you want to make a friend, let someone do you a favor.” Don’t view help skeptically (What did I do to deserve this?) or with suspicion (What’s the hidden agenda here?). Well, sometimes second-guessing is warranted, but not usually. People like helping. If someone offers to introduce you to a person you really want to meet or offers to share assorted wisdom on an important topic, accept the help and express due gratitude. Everyone will feel good—and you’ll actually get closer to the person.

A good way to help people is to introduce them to people and experiences they wouldn’t otherwise be able to access. In other words, straddle different communities/social circles and then be the bridge that your friends can walk over. My passion for entrepreneurship combined with my interest in board game design led me to introduce many of my entrepreneur friends to Settlers of Catan, the German board game. A community in Silicon Valley has sprung up around the game. I’ve also combined my experience scaling consumer Internet products with my interest in cause-based philanthropy to help organizations like Kiva and Mozilla—bridging my network and expertise from the for-profit world to the not-for-profit world. Ben’s experiences and skills make him a bridge between his friends in California and Latin America; between businesspeople in their twenties and businesspeople much older; and between businesspeople and publishing professionals. Can you develop skill sets, interests, and experiences in two or more domains and then act as a bridge for your connections in one circle who want to access the other? If so, you will be enormously helpful.

There is nothing worse than receiving an out-of-the-blue email from someone you haven’t spoken to in three years: “Hey, we met a few years ago at that conference. Listen, I’m looking for a job in the marketing world—do you know anyone hiring?” You think, Oh, I see, you only contact me when you need something.

When a busy person gets an email asking if she knows someone for an open job position or if she can recommend an expert on a certain topic, the people who come to mind will be the people with whom she’s had a recent interaction. Will she think of you when that chance opportunity crosses her desk? Only if you’re top of mind—only if you’re at the top of her inbox or newsfeed.

It’s not technically hard to stay in touch with people. Though you wouldn’t know it based on how frequently you hear someone sheepishly explain months of no contact with, “Sorry, I’m really bad at keeping in touch,” as if dropping someone a quick email were an innate aptitude like sense of direction. In fact, all it takes to stay in touch with the people you know is a desire to do so and a modest amount of organization and proactiveness. You’ve probably heard a lot of the common advice on this front. Here are some nonobvious things to keep in mind.

• You’re probably not nagging. A common fear people have about staying in touch and following up is that the other person will perceive you as annoying and pushy. You write someone and ask if she wants to grab coffee. No response. You forward your email a week later and repeat the question. No response. Now what? Do you come off as needy if you follow up yet again? Well, it depends. But usually not. Keep following up politely if you don’t get an answer—and try to mix up the message, the gift, the approach. With the amount of noise polluting people’s inbox, it’s common for emails to get buried. Until you hear “No,” you haven’t been turned down.

• Try to add value. Check in with someone when you can offer something more than a generic greeting or personal update. Examples: you see his name in the news, read an article he wrote or was quoted in, or know a qualified candidate for a position he is trying to fill. It’s unimpressive to send a note simply asking, “How are you?”

• If you’re worried about seeming too personal, couch your staying-in-touch as a mass action. Does it feel weird reaching out to a high school classmate you haven’t spoken to in years? Here’s a tip that runs counter to the general principle of personalizing your communications: Couch your initial getting-back-in-touch action as part of a more generic process: “I’m trying to reconnect with old classmates from high school. How are you?” This reduces some of the potential awkwardness. Once you’ve eased back into personal contact, then personalize your message.

• One lunch is worth dozens of emails. A one-hour lunch with a person creates a bond that would take dozens of electronic communications. When you can, meet in person.

• Social media. Social media is particularly great for staying in touch passively. As you push one-to-many updates out to your network and followers, if someone you know wants to respond, he or she can. But there’s no obligation. Because many people do not respond to every status update, tweet, or shared article, it can be easy to think no one is reading. But they are. The drip, drip, drip of short, regular updates—even if some border on the frivolous—creates real human connection between you and your online connections. Use LinkedIn to post professional updates; Facebook to post personal updates; and Twitter for updates that may appeal to both groups.

If you’ve fallen out of touch with someone, be the one to reconnect. Dive right back into things, perhaps with a sheepish note up-front saying that “it’s been too long.” Reactivating once strong relationships from school or a previous employer or previous geography is a real pleasure, and it’s one of the easiest ways to build “new” meaningful connections.

You might be nodding your head at the importance of staying in touch. But will you actually follow through? Enacting behavioral change isn’t easy. When you actually have to do the thing you know is important, it’s tempting to push it off for another day. That’s why Steve Garrity and Paul Singh budgeted and precommitted real time and money to staying in touch—so they’d have no excuses when it came time to do so.

Steve Garrity studied computer science at Stanford and interned at start-ups over the summers. After graduating from a master’s program in 2005, he was convinced he wanted to start a technology company of his own in Silicon Valley. But he had spent his entire adult life to that point in the Bay Area and was worried that if he started a company right away, he would be tied down in one location for many more years. He wanted a change of scenery first. So he took a job as an engineer at Microsoft, near Seattle, to work on their mobile search technology. Seattle was a new physical place and Microsoft was a big company—while neither the location nor the big company culture was what he planned to do long-term, he figured the new experiences would be enlightening.

But Garrity had one big worry: What would happen to his network of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, and friends? He knew he would someday move back to start a company. He did not want his local network to become stale. So he made a point to stay in touch with all of his Bay Area connections. Here’s where Garrity got creative. Instead of just thinking about the importance of staying in touch (but eventually falling out of touch, which is what usually happens), he set aside time and money in advance to keep his network up-to-date. The state of Washington doesn’t tax personal (or corporate) income, so Garrity figured he was saving a meaningful amount of money by living there instead of California. Upon moving to Seattle, he declared that seven thousand dollars of his savings would be “California money.”

Anytime someone interesting in the Valley invited him to lunch, dinner, or coffee, Garrity promised himself he would fly to San Francisco to do the meeting. He treated the plane flight like an hour-long car ride. One of his old Stanford professors called him, not realizing Garrity had left town: “Steve, some really interesting students are coming over to my house tomorrow night. I think you’d enjoy meeting them. Want to join?” Steve said yes, and booked his flight to San Francisco. The following evening, he arrived at the professor’s house and knocked on the door with one hand and held a suitcase in the other. Because he had allocated money to follow through on a predecided policy, he didn’t have to worry about the cost of flights or the stress of decision making.

Over his three and a half years at Microsoft, Garrity visited the Bay Area at least once a month. It paid off. After returning to California in 2009, he started a company, Hearsay Labs, with one of his San Francisco friends—a friend whose couch served as his bed during his regular pilgrimages to the Bay Area from Seattle.

Garrity is not the only one who’s figured out that pre-committing yourself to do something makes sure it actually happens. Paul Singh grew up, went to college, and worked his first few jobs all in the Washington, DC, metro area. In 2007 he moved to Northern California to work at a technology company. He was concerned his East Coast connections would wither during his stint on the West Coast. So he set aside three thousand dollars a year to fly back to Washington with the purpose of spending time with his friends out there. In addition to maintaining existing relationships, Paul also used the money to meet new people. He referred to his savings allotment as the “interesting people fund”—money earmarked to stay in touch with or meet new, interesting people. After a few years in the Bay Area, Singh is back in Washington, DC, working as an entrepreneur-in-residence at a small investment fund, an opportunity that arose thanks to meeting his new boss via his interesting people fund. With a bigger bank account, Singh has upped his interesting people fund to a thousand dollars per month, and he uses it mainly to reconnect with the network he built in the Bay Area during his time there.

If you want to maintain relationships with busy, powerful people, you have to pay special attention to the role of status. Status refers to a person’s power, prestige, and rank within a given social setting at a given moment in time. There is no one pecking order in life; status is relative and dynamic. David Geffen is high status in the entertainment world, for example, but perhaps comparatively less so if Steven Spielberg is in the room. Likewise, Brad Pitt is high-status, but put him in a room full of software engineers when the project at hand involves coding, and his status is irrelevant. The President of the United States is often referred to as the most powerful man in the world, yet there are things Bill Gates can do that the president cannot, and still other things that Oprah Winfrey can do that Gates cannot. A person’s status depends on the circumstances and on who’s around.

You won’t read about status in most business and career books. It is a topic often dodged in favor of bromides like “Treat people with respect” or “Be considerate of the other person’s time.” Good advice, but not the whole story. The business world is rife with power jostling, gamesmanship, and status signaling, like it or not. It’s especially important to understand these dynamics when you work with people more powerful than you.

Before Robert Greene became a bestselling author, he worked for an agency in Hollywood that sold human-interest stories to magazines, film producers, and publishers. His job was to find the stories. A competitive person, Greene wanted to be the best, and sure enough, as he recalls, he was finding more stories that got turned into magazine articles, books, and movies than anyone else in his office.

One day, Greene’s supervisor took him aside and told him that she wasn’t very happy with him. She was not specific, but she made it clear that something just wasn’t working. Greene was befuddled. He was producing lots of stories that were being sold—wasn’t that the point? There was something else. He wondered if he was not communicating well. Perhaps it was just an interpersonal issue. So he focused more on engaging her, communicating, and being likeable. He met with his boss to go over his process and his thinking. But nothing changed—except for his ongoing success at finding really good stories to sell. Later, during a staff meeting, the tensions boiled over, and the supervisor interrupted the meeting and told Greene he had an attitude problem. No more detail, just that he wasn’t being a good listener and had a bad attitude.

A few weeks later, after being tortured by the vague criticisms despite his solid work performance, Greene quit. A job that should have been a stellar professional success had turned into a nightmare. Over the course of the next several weeks, he reflected on what had gone wrong with his boss.

He had assumed that what mattered was doing a great job and showing everyone how talented he was. While doing a great job was certainly necessary, he concluded it was not enough. What he failed to recognize was how his personal talents might make his boss look diminished in the eyes of others. He failed to navigate the status dynamics around him; failed to account for the insecurities, status anxieties, and egos of everyone else. He failed to build relationships with the people above him and below him on the totem pole. And ultimately, he paid the price with his job.

All men are created equal and endowed with inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, rights guaranteed regardless of gender, race, or religion. If a man commits a crime, he may lose his liberty but not his basic human rights such as food and humane living conditions (at least in enlightened societies, anyway). No one is more human than the next person. If you breathe, you deserve basic dignity. Period.

But in other ways, people are not equal. We do not live in an egalitarian society. People make different choices. Good luck falls on some more than others. Compare two men who work in finance, wear a suit and tie every day, and live in New York City. On the surface they may seem to be equal in status, but in reality one person will always be (and be perceived as) relatively more accomplished, powerful, rich, intelligent, busy, or famous than the other.

Status differences—both real and perceived—bear on how you are expected to act in different social situations. The following scenarios show how inappropriate power moves can offend someone of equal or higher status, and how to avoid making them.

• You email the vice president in charge of hiring at a company you want to work for. You send your résumé and propose to meet at a coffee shop near your house.

A meeting should usually be made more convenient for the higher-status person. That means at the time and location best for him or her. When corresponding with higher-status people, propose to meet “in or near your office.”

• You show up late to a meeting with a fellow product manager.

Tardiness is the classic power move because it says, “My time is more valuable than yours, so it’s okay for you to wait for me.” To be sure, we’ve all been late due to circumstances out of our control, so it’s not always a reliable signal. But usually it says something. Think about it: Would you allow yourself to be late to a meeting with Barack Obama? Certainly not.

• You and your coworker are both marketing assistants at your company. He mentions he’s working on a sales proposal. You proactively say, “I’d be more than happy to take a look and tell you how it could be improved.”