CHAPTER 4

VICTORIAN EXPANSION AND INDUSTRIAL BREWING

1860–1900

One might be forgiven for thinking that the history of brewing in Ontario should have closely mirrored the history of the whole of Canada. There was one specific date that set the course of Ontario’s brewing history in the mid-century, and it had nothing to do with Confederation. If you hadn’t subscribed to the London Free Press, it is possible that you would have missed the following paragraph on December 29, 1858:

THE SARNIA BRANCH—The first passenger train on this road arrived here yesterday fore-noon. There were a number of passengers from Sarnia and the other stations along the route. The merchants of this city will find this road a great convenience, as it will enable them to compete with their Detroit friends in supplying the Sarnia people with those commodities purchased in the eastern markets. A large quantity of freight was yesterday shipped for Sarnia, among which was 30 barrels of beer and 50 dozen of ale, from the celebrated brewery of Mr. Labatt of this city.

Just before the New Year in 1859, the rules changed. Beer remained heavy, but the roads no longer mattered.

John Kinder Labatt was almost certainly not the first brewer to ship his product by rail in Ontario. This brief article illustrated a number of the driving factors that would shape the Ontario beer market in the latter half of the twentieth century. Rail defeated distance. Suddenly, a town just over one hundred kilometers away from London became a regular fixture in Labatt’s sales territory. Not only did this provide Sarnia (a city without a brewery of its own at the time) with a constant supply of fresh beer, but it also discouraged Sarnia’s residents from purchasing beer across the river in Port Huron, Michigan.

In one gesture, no doubt simply meant as celebration of a newly completed rail line, we have technological advancement, capitalist expansion and economic protectionism. It was also one of the first successful staged public relations events for an Ontario brewery. It made the paper, after all.

THE RAILWAY

Rail did not spring up fully formed in Ontario, or indeed anywhere on the North American continent. It was typically envisioned as a primarily local service that would be beneficial to the points that it created a path between, but the owners were not insensible to the rapidly growing network. If you take the Toronto and Guelph Railway as an example, the report of the board of directors in 1853 (its second year of operation) made it clear that the members were extremely proud of the work that they have accomplished; however, an amalgamation with the Grand Trunk Railway would result in their line expanding into the distance as far as Sarnia and possibly Chicago beyond.

The Grand Trunk Railway included several smaller companies at the time of its creation in 1853. By 1859, it would span just over eight hundred miles to Portland, Maine, from Sarnia, Ontario. In 1856, the line along the St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario to Toronto was completed. It reduced the amount of time spent in travel between Montreal and Toronto to fourteen hours from just over two days by steamboat. Southwestern Ontario had its own rail company in the form of the Great Western Railway. The Great Western focused initially on the creation of shorter lines that would connect what we now think of as neighbouring communities. In 1853, it created two lines: one from Hamilton to the suspension bridge at Niagara Falls and another from Hamilton to London. The next year would see the London line expanded to Windsor.

By 1855, a branch line had been constructed from Hamilton to Toronto. For the time being, Toronto was an afterthought to the Great Western Railway, which was looking to take advantage of the increased trade in raw materials with the United States brought about by the sudden lack of tariffs. Inevitably, as rail became the dominant mode of travel in Ontario, additional lines were created in order to connect small farming communities and market towns that had originally depended on water routes for their prosperity.

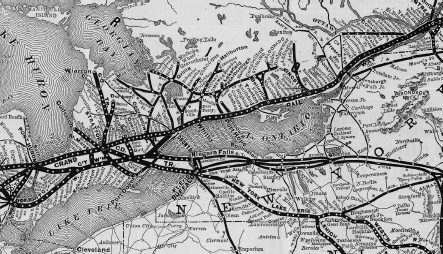

This detail from the Grand Trunk Railroad map of 1887 highlights the strictly regimented distance between stations and the orderliness that had been imposed on what was a wilderness only fifty years prior. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Every point on the main lines between Windsor and Cornwall had been laid out based on access to the lakefront and rivers that the province’s original surveyors felt crucial. If you leaf through the maps chronologically, the advancing cables of steel provide a sense of well-regulated arterial structure to a province that is becoming an economically dominant organism. A look at the Ontario rail system by the end of the century, especially in comparison to those in Michigan or Ohio, puts one in mind of the unofficial national motto: “Peace, Order and Good Government.”

The timeline of expansion into branch lines has a special significance for the brewing industry in Ontario. From a relatively early point in the 1850s, shipping beer by rail became a possibility. Because of the manner in which the two main lines were situated, this new technology disproportionately benefited urban brewers. London became a stop on each rail system, as did Guelph and Toronto. Hamilton was a hub dictating traffic in every possible direction. Breweries that were astute enough to avail themselves of the opportunity would thrive.

It should be stressed that market dominance did not come immediately. The initial generation of settlement of much of Ontario was still occurring by the time the railroads begin to stretch across the province. By 1862, there would be 155 breweries within the province of Ontario, a number that is suggestive of the realities of brewing locally and without refrigeration. Each town large enough to support a brewery of modest size did so. Thanks to the advent of rail, that situation would quickly become untenable. By 1902, only 62 breweries had survived.

MASS AGRICULTURE

With the steel ties of the railroad inexorably binding together local economies, some things would change forever. While Ontario is generally incredibly fertile, different districts produced crops at varying levels of quality. Unlike today, when we think of the prairie provinces as being the breadbasket of Canada, Ontario was largely independent in terms of the production of grain in 1860. Grain exports were an important driver of local economies. England’s Corn Laws had long since been repealed, creating a situation in which a considerably higher price could be demanded by the colonies for high-quality wheat and oats. These prices did not vastly fluctuate from year to year given England’s size and demand for each crop in the face of increasing population. Wheat would be a stable choice for a farmer in Ontario, presenting a steady yield per acre and a reasonable return on cautious investment. Barley was a more speculative crop with unpredictable outcomes on a year-to-year basis. It would provide some return on investment, but how much was left in some ways to chance. The quality of the barley afforded by the soil could make a substantial difference.

The area surrounding the Bay of Quinte in Hastings and Prince Edward Counties was uniquely positioned to take advantage of an extraordinary set of circumstances. Geographically, they were within reach of Oswego in New York State, a barley-hungry town that would supply grain to brewers throughout upstate New York. Economically, the Elgin-Marcy Treaty of 1854, which ensured reciprocity of trade, meant that there were no tariffs in place on grain shipped across the lake. The American Civil War created a truly significant demand for the product. In 1862, President Lincoln passed an excise tax on whisky, effectively increasing the price per bottle tenfold. As beer remained untaxed, production and consumption would increase dramatically. When you add to the mix the general loss of labour and production capacity to the Civil War and the expansion that continued westward in spite of it, it is clear to see why barley became Ontario’s cash crop.

In 1863, the year after the declaration of the excise tax, we have some idea of the quantity of barley exported and from whence it came. Toronto listed 288,108 bushels of barley, all of which was shipped directly to Oswego. At 48 pounds to the bushel, that comes to just under 14 million pounds of barley. Prince Edward County put that figure to shame, having harvested and exported more than double that amount for the duration of its “Barley Days.” One need only stroll through residential neighbourhoods in Picton to see the lasting economic effect. Its showpiece Crystal Palace in the fairgrounds is a testament to the wealth that barley created.

Even after the reciprocity treaty ended in 1866, the quality that Ontario’s barley harvest ensured meant that Americans would continue to seek it out even with a mild tariff imposed. On average, between 1882 and 1890, the total figure for the province was 750,000 acres planted, producing 20 million bushels. The average price per bushel in a good year might climb as high as a dollar. It was not until 1890 that the McKinley tariff would prove catastrophic for Ontario’s barley farmers. The tariff of thirty cents per bushel nearly halved the asking price and largely destroyed its profitability as a crop for export to America. Some discussion was had in the Globe in May 1890, contemplating the possibility of switching to a separate crop of two-row barley for export to England—a statement that came after acknowledgement that only half as many acres would be planted that year. The majority of the 1890 crop would end up as fodder for animals.

AGENCIES

Prior to the advent of rail, each brewery needed a system of distribution in order to make its business viable. There was always the possibility of short-distance delivery by wagon within a certain circumference of the brewery, but this was an untenable solution beyond a certain distance due to the logistics involved. The obvious solution was to transport beer using existing services as agencies.

In the case of a number of urban breweries—those with the ability to take advantage of the limited advertising that local newspapers would provide—arrangements could be set up with cartage firms or depots. The depots need not have been a great distance from the brewery. In the case of the Spadina Brewery in Toronto, purchases could be addressed to its depot on Queen Street, much closer to a more populated area. Orders could be filled in lots of a dozen bottles, a quantity that has remained stable to this day.

Even before the advent of rail in Ontario, there had been some distribution through cartage firms to remote towns. Breweries were typically not yet large enough to be able to negotiate the minutiae of local sales on their own behalf, and as such they would entrust their business to a single representative. Typically, this might be the owner of a dry goods or grocery store. Aside from taverns, there was not enough variety to warrant specialty stores for beer. As breweries grew in size, they would ship to a larger number of towns, resulting in a situation where a single agent might represent several different breweries.

With a rail system solidly in place, it became possible for breweries to take advantage of one of the largest and most orderly systems of transport in North America. For one thing, the quantity of beer shipped changed dramatically between 1860 and 1900. Instead of being able to simply fill bottled orders for a nearby agent, beer could be shipped for hundreds of miles in barrels or hogsheads and bottled at the other end of the line. The reduction in transit time meant that, even if unrefrigerated, there would be little loss of quality due to the high turnover in market towns with sizeable populations.

Before we detail the rise of the giants of brewing in Ontario, some consideration should be given to those smaller breweries that sprung up midcentury. In a history of this length, it is impossible to enumerate all of the breweries that existed. Some small-town brewers may well find themselves without equal representation in these pages, but then, not all breweries are created equal. Let us nevertheless press forward with a brief tour of the province’s roll call at the point of decline in 1870.

Eastern Ontario and Ottawa were relatively slow to develop a number of breweries representative of their populations. In Ottawa itself, there was George Stirling’s Dominion Brewery on the Ottawa River near St. Patrick. It’s within earshot of Notre Dame and has been happily occupying its spot since 1851. It had pride of place near the market, making it competitive with the other two large breweries. The Rochester-owned Victoria Brewery was the oldest of the established breweries in the nation’s future capital. John Rochester helped his older brother, James, found the brewery in 1839 at the age of seventeen. It was located out on the Lebreton flats near the Chaudières. The Rochesters, as a clan, owned a surprising number of businesses and were, as a result, massively politically connected. John Rochester was actually selling the brewery to his older brother, James, so that he could concentrate on being mayor. It was older, and while active, it was not producing a huge quantity of beer.

The Union Brewing Company was the coming thing. Founded in 1865, it was initially owned by a partnership, but the man doing most of the work was Harry Fisher Brading, who was a brewmaster by trade. In 1867, Brading bought out John Atwood, leaving him partnered with Henry Israel. Brading and Israel were located in a position near Sparks and Wellington to service Ottawa proper, but they were also near the fringe of the city and could take advantage of rural markets and the particularly thirsty lumberjacks and log drivers.

Along the St. Lawrence, Brockville was more or less an open market. Bowie and Company set up shop in about three years before becoming Bowie and Bate in 1877. Cornwall was similarly underserved, but no one was going to rectify that problem for a while. It is on the St. Lawrence, so it was not like it didn’t have access to beer from other places. Prescott was a different matter, due to the presence of Ogdensburg across the river. Ogdensburg was an important railway junction, and there were a number of lines that passed through it. Prescott had been connected to Ottawa by rail since 1852, and it was a transfer point for the Grand Trunk. As a result, it was a very sensible choice as a location for a brewery. Robert and Ephraim Labatt purchased the Prescott Brewing and Malting Company in 1864 from their older brother, John, who had gone into business with George Weatherall Smith. Smith relocated temporarily from Wheeling, West Virginia, when the question of secession made Wheeling’s future uncertain.

John McCarthy and James Quinn had just opened a place of their own about a mile west of Prescott. They were brewing two beers, differentiated by the brands “XX” and “XXX,” in a steam-powered tower brewery that ought to have been the envy of the industry. McCarthy knew what he was doing in terms of brewery appointments. He had been working in brewing or distilling in Prescott since he was twenty and fresh off the boat from Dundee. The cellar had room for two thousand barrels, and the beer was comparatively low in alcohol for the time, so they were churning through that capacity.

In Kingston, George Creighton’s Frontenac Brewery was tooling along, but it was destined to serve the local market due to its small size. The cellar seemed to hold about 150 barrels. Joseph Bajus down on Wellington Street was slightly more ambitious, having added a three-story tower to the premises when he purchased it in 1861. If he was not brewing lager initially, he would be shortly. Hayward and Downing had their brewery on the other side of downtown quite near Queen’s University. According to the style of the time, they went with a railway motif under the name Grand Trunk Brewery. It’s likely that they supplied the railway itself since Kingston was the lunch stop. Kingston had a large enough local population, but it had lost its primacy as a brewing centre and would face numerous closures before the turn of the century.

Later in the Victorian period, as Labatt’s labelling and branding further evolved, the India pale ale label was designed, replete with medals and arrowhead trademark. Despite attempts to create a unique brand, Labatt did have imitators. Courtesy of Molson Archives.

Farther west, in Prince Edward County, there was the Pickering Brewery in Picton. It was basically just large enough to support the town. Belleville had the Roy Brewery on Front Street—two of its competitors went under in the 1860s. The Hastings Brewery lasted four years, while the Moira Brewery existed for slightly more than a decade. Within a few years, William Severn would open a brewery, but at the time, if you were in Belleville, you were drinking Roy’s.

In Cobourg, James Calcutt has sold out to the MacKechnie brothers, who renamed the establishment the Victoria Brewery. James Calcutt himself had moved west to Port Hope, and his son, Henry, had moved to Peterborough, an area that had been waiting for a brewery of some size. James Calcutt’s competition in Port Hope was Thomas Molson, but the focus of his plant was distilling, and it closed in 1868. West of Peterborough, there was the Victoria Steam Brewery in Lindsay, an unnamed effort in Cannington and a brewer in Orillia by the name of W.W. Jackson. Barrie was more prosperous, and Robert and Thomas Simpson had been brewing since 1851 at their Simcoe Steam Brewery, although Robert had been brewing in the area since 1836. The Anderton Brothers set up shop in 1869 less than one mile away.

Around the southern shore of Georgian Bay and Lake Huron, there had been some activity. Collingwood had a brewery for two years in the early 1860s. Owen Sound had Henry Malone making a go of things for twenty years. Kincardine, Bayfield and Seaforth all had people whose sole occupation was listed as brewer. Chatham was currently without a brewer due to an inexplicable decade-long closure of Henry and Joseph Slagg’s Chatham Brewery. Sarnia had the Sarnia Brewery, and Sandwich, near Windsor, also had an eponymous brewery.

The vast majority of these breweries would disappear before the turn of the century. There are numerous reasons why they were prone to failure. Truth be told, fire claimed as many breweries as temperance ever would. Breweries that had sprung up quickly in order to serve a community would usually have been of wooden construction, and even a stone structure was no guarantee of safety. It might have been as simple as a horse kicking over a lantern in the brewery’s stables. It might have been a young employee sampling your wares instead of watching the malt kiln; perhaps the sacking used in the process caught while unobserved. If you were particularly unlucky, an act of God might lay waste to your brewery and the entire neighbourhood surrounding it, as it did in the case of Ottawa’s Victoria Brewery and the Lebreton Flats in 1899.

On a long-enough time frame, it was far more likely that a brewery would catch fire than not. The only question would be the extent of the damage. While brewers certainly carried insurance, it was typically the buildings and equipment that would be insured. Due to the extraordinarily rapid expansion of brewery volumes during the period, it was almost a certainty that the policy would come nowhere near covering the ingredients in process or the beer in storage. Even if the policy were up to date, in some cases the brewer simply did not have the will to rebuild. In the case of the Kensington Brewery in London, this was certainly true. Robert Arkell’s insurance covered barely half of the loss, and despite the comparative success he had enjoyed, he never rebuilt.

Brewing is a fundamentally generational business. There are instances of dynasties like the Labatt, Molson or Kuntz families—situations where the ownership has been kept largely under family control. These are the exceptions. Typically, the business does not advance to a second generation. The brewery will simply begin and end with the founder. In many cases in rural Ontario, the brewery would be profitable enough to ensure a comfortable living, but given the amount of opportunity available, it might not have seemed the best bet for someone in a family’s second generation.

To keep an inherited brewery open at its current size would mean that your production volume would remain the same. For that reason, the distribution area would not increase. Even with additional volume, establishing the agency contacts necessary to sell beer in other towns was laborious. Barley, as we’ve seen, could vary greatly from year to year in price, meaning that margins might be unpredictable. Further, with each passing year, there would be more breweries from other markets attempting to acquire agents nearby, entering the local market on their terms with a head start because of their rail connections. Competing would require not only capital for expansion but also enough drive and interest in the business to sustain a brewer’s ambition.

THEIR TERMS

While the first breweries in Ontario might have been based out of taverns or homesteads, and the second wave involved professional brewers making enough beer to satisfy local demand, the third wave in the 1860s and 1870s was gargantuan by comparison. The breweries were massive, with huge facilities and capacity that boggles the mind relative to the population of the province at the time. In 1861, the population hovered around 1.4 million people, and that figure would increase by 50 percent before the turn of the century. Ontario’s breweries produced vastly more beer than was needed to slake their thirst.

It is at this point in the history of Ontario that names emerge whose legacy has spanned a century. Labatt, Carling, O’Keefe and Sleeman are all brands with which we’re familiar, and it was the actions of these brewers in the last decades of the nineteenth century that have ensured the survival of their reputations. The commonality that they seem to share is a vision for the scale of enterprise that would be required to ensure their continued success, as well as their willingness to face the financial risks that went hand in hand with the attempt.

In the case of the Carling Brewery, the hand guiding the tiller was John Carling, who, along with his brother, William, purchased the brewery from his father, Thomas, in 1849. The success of his brewery mirrored that of his political career. First elected as a local politician sitting on the school board of London, he worked his way up to become receiver general for the Province of Canada and, subsequently, Ontario’s commissioner of agriculture and public works. Under John A. MacDonald in 1891, he was named minister of agriculture. During this period, he instituted a number of Ontario’s experimental farms and oversaw the construction of several important public buildings in London. John Carling was a man who saw the potential of building for the long term, and he certainly understood that having his finger on the pulse of the nation’s business was good for his own.

While the Carling Brewery had never been a small affair, it was comparatively ramshackle. It comprised several buildings on Waterloo Street that had been added to as the need arose. By 1860, it was the third-largest business in London, producing 3,600 barrels of beer annually. That figure would nearly triple by 1867, ranking it among the largest breweries in the province.

Seeing the need for additional room in which to grow, the brewery began construction in 1873 of a state-of-the-art facility with a much larger capacity. The new location at the corner of Ann and Talbot had access to a spring that produced sixty thousand gallons a day. It could malt eighty thousand bushels of barley per year (fully one-third of that exported from Toronto by boat). Rather than horsepower, the brewery was rigged for steam and had an annual capacity of seventy thousand barrels, enough to serve every resident in the province ten pints. This was an optimistic estimate of the company’s potential and came with a hefty price tag of $100,000. A separate lager brew house was added in 1878, increasing the capacity a further fifty thousand to sixty thousand barrels. Communications throughout the buildings were handled by a newly installed telephone system—having been invented in Brantford two years earlier.

This 1889 image of the Carling Brewery in London, Ontario, was taken after the plant’s renovation in the wake of a devastating fire that left only the shell of the building intact. Courtesy of Toronto Public Library.

On February 13, 1879, disaster struck when one of the brewery’s four new malt kilns overheated and created a catastrophic blaze that would destroy all but the bones of the new brewery. William Carling subsequently passed on as a result of pneumonia contracted while attempting to put out the fire. In addition to the personal tragedy, the damages neared $250,000, a figure that did not even cover the stock contained within the brewery, let alone the building itself.

The Carling brewery underwent massive reconstruction efforts, possible due only to the clever design that left the outer walls and brickwork intact. By the first of May, the brewery was up and running again. One cannot help but feel that the speed of the reconstruction had much to do with the esteem in which the citizens of London held Mr. Carling. It is also likely that his forays into the political arena eased his access to a loan from the Bank of British North America. Regardless, the effort was truly astounding. A phoenix motif was adopted in illustrations of the brewery for years afterward.

By the end of the century, Carling would have a complete network of agents throughout Ontario, but additionally, it would have established sales in every major regional hub accessible by rail in Canada. Attempts to expand into the United States would see the establishment of a short-lived brewery in Cleveland and agents in Detroit. Once a year, there would be a shipment of amber ale and porter to Hong Kong. It is difficult to say whether there was a legitimate demand, or whether it was in part a diplomatic gesture from Canada’s minister for agriculture.

The story of Labatt’s success is remarkably similar, even if it is on a slightly smaller scale. The original Labatt Brewery succumbed to fire in March 1874. Nothing could be salvaged, and the insurance did not even cover the malt that was on hand for the spring brewing season. Having expended the effort to build a sales network, rebuilding, if it could be accomplished quickly, was a comparatively safe bet. John Labatt would run through his personal savings and investments and a significant portion of the family’s fortune, which was in those days under the control of his mother.

At the time of Confederation in 1867, Labatt brewed about half of the volume that Carling could boast, but after the construction of a new and efficient brewery, Labatt could manage thirty thousand barrels a year, with facilities to produce far more malt than would be needed for that capacity. What stock there was would take advantage of the comparatively new technology of refrigeration. He would trade in malt across Canada as far away as Halifax, perhaps foreshadowing the relationship that the Labatt and Keith’s breweries would share more than a century later.

Where existing facilities for brewing stood, improvements were made. Where brewers dreamt of success, giant facilities sprang to life. The William Street Brewery in Toronto stood on the west side of University Avenue, very close to Dundas Street. For sheer scope, it was the largest malt house in Canada. Built by John Armstrong Aldwell in 1859, the William Street Brewery had an initial malting capacity of sixty thousand bushels a year, with the ability to brew nineteen thousand barrels a year. Additionally, it was one of the first Ontario brewers to employ its own travelling salesmen in place of agents. The Globe, writing in 1868, was not insensible to the massive capacity:

Their manufacture enters largely into competition with the Montreal ales in that city, while on the day of our visit an assortment in bottles capable of making a good sized town hilarious, was being shipped to the Bruce Mines, the manufacture of all of this is accomplished by machinery, and manual labour enters less into the calculation of cost than in many smaller establishments of a similar kind.

In 1868, its new six-story malt house was prized not only for its utility but also for its attractive and efficient architectural features. Previously, malt houses would have employed direct-fired kilns. In the case of Aldwell’s malt house, the furnace was in the basement, and the five-story kilns were heated by a series of vents and flues. The total capacity annually was 220,000 bushels of barley. The 10.5-million-pound yield made it the second-largest malt house in North America behind Greenwood’s in Syracuse, New York.

Aldwell was a savvy businessman. To give some idea of the scale of his ambition, in 1871 he was involved in an arrangement with the City of Toronto to open a sugar refinery. It was so large a project that the city agreed to exempt it from taxes for a period of twenty-one years. Sadly, Aldwell did not end well, passing away in September that year at the tender age of forty-seven. Had he lived, it’s likely that the face of the brewing industry in Ontario would have a different complexion. As it was, the concern became the Toronto Brewing and Malting Company in 1874—a company prodigious in its own right.

While sheer volume was an indicator of progress for breweries in Ontario, progress could similarly be measured by the technology in use. Equipment for scientific measure of various facets of the brewing process was available by mail order through newspapers in the 1840s. By the 1880s, the province had a supremely efficient rail system, telegraph and telephone and acted as a cultural crossroads between Britain and America. Ontario was at the forefront of technological development, even managing in some instances to contribute. It certainly did in the brewing industry.

The Calcutt Brewery of Peterborough provides an excellent illustration of the changing times. The brewery retains its crest and motto despite the change from Extra Stout Porter in the 1890s to Trent Valley Lager after prohibition. Courtesy of Molson Archives, Jim Maitland.

George Sleeman of the Silver Springs Brewery in Guelph was awarded a patent in 1873 for a jacketed fermenting tub that could control the temperature of the beer inside by regulating the rate of flow of water around it. It was a vast improvement on the overcomplicated device that Kingston brewer Aaron W. Lake had patented just three years earlier. Henry Calcutt of the Calcutt Brewery in Peterborough held several patents, the most impressive of which is the 1893 patent for a particularly efficient flue boiler with increased surface area for faster heat transfer in the brew house. This was an improvement on his 1881 attempt to patent sparging as a technique.

Perhaps the most impressive innovation was that of Thomas Frederick White of Port Colborne, who in 1898 patented a design for a beer filter that was not substantially different from those in use today. It was seemingly an early version of a plate and frame filter that is doubly impressive for the reason that it was modular and could be expanded depending on the amount of beer to be filtered.

ADVERTISING

If the model for success in brewing in Victorian Ontario was to centralize production in a single enormous facility with all of the modern conveniences, the model was not a secret. While smaller brewers fell by the wayside, competition began to grow in markets across the province as large brewers competed in earnest for the first time. In market towns with rail access around the province, consumers suddenly had an overwhelming number of options available to them, where as little as ten years earlier, there had been only the local brewer.

The advantage of being the local brewer in a pre-rail Ontario was the fact that there was very little competition, and as such, there was no real need to differentiate one’s product from other products. Newspaper advertisements prior to the growth of rail would typically advertise two facets of the business. The first was the fact that it was an ongoing concern at a certain address. The second was a short listing of whatever few types of beer might have been available. For a typical ale brewery, this would be an amber or pale ale and some manner of porter. In the case of adventurous ale brewers, they might go so far as to sell a blended version referred to as a half and half. Lager brewers typically sold one kind of lager.

The development of branding in the late Victorian period can be observed in the evolution of Labatt’s labels. The first does not even name the brewery that has created it, focusing only on the type of beer contained. Courtesy of Molson Archives.

As branding progressed in the late Victorian period, Labatt’s labels featured the brewery name. Courtesy of Molson Archives.

Within a period of twenty years, breweries were competing for customers in far-flung cities and towns halfway across the province. The largest brewers from Southern Ontario were shipping beer to Thunder Bay and Silver Islet as early as the mid-1870s, prior to Conrad Gehl’s brief attempt at constructing a local brewery to service the miners. Gehl’s brewery was seized in 1877 by the government for failure to first obtain a license to brew, but it was allowed to reopen after the fifty-dollar fee was paid.

Brewers were also competing with other messages and movements in society. The temperance movement was becoming a strong political force, with thousands of Upper Canadians taking the personal pledge. As temperance became a political movement, it took on prohibitionist principles. Church leaders and reformers lobbied for legislative action in the 1850s to allow a local ban on booze.

The Canada Temperance Act of 1864 confirmed municipal power to hold a vote on whether to go dry. After more than a decade of relative quiet, the city of Toronto finally voted in 1877, and detailed minutes were kept by a committee of those successfully campaigning for the “no” side. At one meeting, Eugene O’Keefe stood to speak on behalf of the drinking of light wines and beers. At others, tavern keepers objected to the claims of lawlessness, pointing out how other routes to drunkenness were far more problematic. A Mr. Waterhouse shared the example of “a case of wholesale drinking at a public boarding house, where 18 galls. of beer were brought in, and the result was, that in less than four hours, everyone of the eighteen boarders in that house was drunk, and the old woman in disgust threw the keg into the yard.”

As temperance expanded, breweries and rail lines also extended their reach. One significant problem they faced was the way in which identification with the breweries lagged behind the new province-wide demand for their beers. For example, several breweries operated under the name “Dominion,” including ones in Hamilton and Toronto. At one point, there would have been at least five breweries referred to as the “Victoria Brewery” across the province—a situation that would lead to confusion for customers should agency sales tick up. The need to differentiate products from one another in order to remain competitive led Ontario brewers to adopt labels increasingly colorful in both their language and design.

Brewers increasingly adopted trademarks that would make their brand stand out on the shelf. In some cases, these would simply be monogrammed initials, as in the case of the O’Keefe Brewery in Toronto. By the time Arthur Anderson took over the Victoria Brewery in Ottawa, the brand’s identity had become a double A. The Grant and Sons Brewery in Hamilton would use the same superimposed monogram to identify its bottles.

A portrait of the staff at the O’Keefe Brewery in Toronto near the turn of the century. Courtesy of Toronto Public Library.

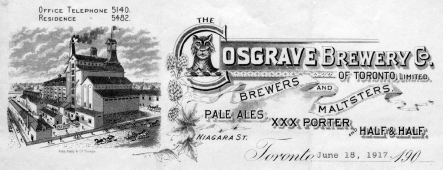

More usually, a simple image would suffice. The Davies Brewery would use a five-pointed star in yellow and white to represent itself. The Walkerville Brewery in Windsor would use a series of stars and crosses. Ambrose and Winslow in Port Hope chose the less symbolic but more useful corkscrew as its logo. Cosgrave in Toronto would go with a stag or horseshoe—or, in later examples, a combination of both—before settling on what can only be referred to as a goofy-looking tiger. Several breweries would use the beaver as a symbol, which has persisted to this day in the case of the Sleeman Brewery.

Simply creating an identity for the brand was not enough. While brewers had always made different varieties of beer, the necessity of creating a memorable name for their products eventually led to creativity. Instead of simply producing an amber or pale ale, breweries were suddenly producing cream ale and crystal ale, sparkling ale and “XXX Diamond” pale ale. India pale ale was a certainty by this point in the nineteenth century, but O’Keefe produced an imperial pale ale. MacKechnie’s Victoria Brewery in Cobourg was producing an “EXTRA HOPPED” pale ale. Walkerville produced a Canadian pale ale in a clear bid to take advantage of cross-border traffic.

Thomas Davies’s Double Stout featured a circular label with the maple leaf and barrel trademark. Courtesy of Molson Archives.

This detail from the Cosgrave Brewery’s stationery displays its decision to stick with the styles of ale that it was used to well into prohibition. Also, note its ill-conceived tiger mascot. Courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.

It was no longer sufficient to put one’s stout on the market as it stood. It required an identity, whether that be imperial stout, XXX stout, double brown stout or extra stout. In one wonderfully evocative example, the Davies Brewery in Toronto marketed a sable ale. It is likely that all of these beers were already being brewed by the time it was necessary to identify them with colourful labels. It is not as though there was a sudden burst of stylistic diversity in 1870. It was just that marketing had not been of as much value before that point.

In the last three decades of the century, brewers would define the strategy of marketing beer in order to better avail themselves of distant consumers. Some of the techniques are still in use and will be immediately identifiable to a modern audience. The first is simple and entirely understandable when one considers the amount of vibration beer would have been subject to as it was shipped by rail and the speed with which it would be consumed at the other end of the voyage. In order to prevent customers from accidentally being turned off their brand, breweries would apply notices that the bottle should be stored in an upright position for twenty-four hours before being decanted, carefully and without shaking. Clearly, the lack of filtration technology meant that some bottles would contain sediment as an ordinary part of the experience. Not only did this result in the best experience for the consumer, but it also portrayed the brewery as caring deeply about the quality of its product. It was an early form of built-in beer education.

A second technique that entered common usage was the declaration of the ingredients used in brewing the product. It should go without saying that the majority of breweries would have used only the basic ingredients: hops, malt, yeast and water. While rice would crop up as an adjunct for some breweries toward the end of the century, it cannot be thought of as exactly unwholesome.

A popular extension of this concept was to have a chemist analyze the product so that advertisements in newspapers could declare that the beer had no unnatural additives and was unadulterated in any way. This also had the benefit of casting aspersions on the competitors that had not thought it necessary to retain such a chemist. Taken to its logical extreme, the results were unsettling. The Rock Brewery in Preston would eventually claim to be “Brewed from the famous Spring Water. Pure and Free from Drugs and Poisons.”

Thirdly, there was the inclusion of credentials. If the beer had won an award, it was in the maker’s best interest to let the public know about it. Labatt’s India pale ale, for instance, incorporated the first two medals that the beer won at international competition directly into the label. There would be no way of mistaking its pride in its product.

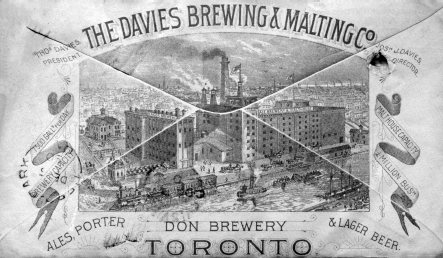

This envelope from the Davies Brewing and Malting Company in Toronto highlights the pride brewers took in their accomplishments. It lists the variety of products, quantity of malt and a production capacity of nearly ninety thousand barrels per year. Courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.

Toronto’s Dominion Brewery would note in the margin of the label for its India pale ale that it had been “awarded highest honours & medals at the North Central and South American Exposition New Orleans 1885 against Bass & other celebrated English Brewers.” Why would the consumer even consider buying Bass when a locally produced beer had beaten it at a prestigious competition? Marketing it may have been, but there is the real possibility that Ontario’s beer would have been of a quality comparable to that in England after only sixty years of industrial-scale brewing.

LAGER

Except for eastern centres like Kingston, by the end of the nineteenth century, lager would make up a quarter of the total volume of beer sold in Ontario, although there is some reason to doubt that commonly accepted figure. There is the possibility that it is significantly lower than the real figure.

One of the difficulties in the regulation of the brewing industry in the rapidly expanding province of Ontario in the late 1860s was keeping accurate records in order for the government to collect the duty owed it. Given that the figures were collected annually, and that they were supplied by the breweries themselves, inaccuracy was a real concern. For one thing, brewery production would have increased on a yearly basis as the population of the centres around each brewery expanded. For another, there has always been the temptation for a business that is not being scrutinized to underreport its sales.

It did not help that some of the agents acting on the behalf of the government were grossly incompetent. In 1866 and 1867, two agents named Godson and Romain were tasked with an investigation into the sales figures of the lager breweries in Waterloo County. Suspicions had been raised when it became apparent that the total volume reported for the 1865–66 brewing season was 78,552 gallons of beer, or just over 2,450 barrels. This laughably low figure represented the total reported output for thirteen lager breweries in Waterloo County. The charge of fraudulent sales made it clear that a single brewery was selling more than half of that amount annually in the lager saloons of Hamilton alone. It meant that no one was paying any taxes.

The agents performed a perfunctory two-day tour of a handful of breweries in the county, taking testimony from brewers whose natural inclination would have been to lowball the figures. Even those dubious accounts vastly outstripped the reported volume. Upon declaring the allegations unsubstantiated, Godson and Romain were given a sound drubbing in the newspaper for their incredulous gullibility. This episode illustrated the fact that the sales of lager in Ontario at Confederation could easily have been five or even ten times as high as common wisdom would suggest.

There were many facets of brewing lager that could be advantageous to brewers. In terms of courting public opinion, lager was viewed as a beverage of temperance, which helps to explain the timing of its adoption. The passing of the Canada Temperance Act in 1878 meant that local-option prohibition was a possibility. This fact was not lost on Eugene O’Keefe, who had provided testimony at local-option hearings. He took out a full-page spread in the Globe barely a month after his lager and pilsner were introduced: “Messrs. O’Keefe and Co. contend that the benefits accruing to the country by the introduction of first class malt beverages cannot be over-estimated, and will tend more to the interests of TEMPERANCE than all the legal enactments and repressive measures that any Government may introduce.”

The advertisement goes on to claim that religious dignitaries from Buffalo were of the opinion that lager was second only to religion in terms of restraining drunkenness and that the working-class population had been weaned off anything stronger. Not only is lager good for society, but the hops also come from Nuremburg! The brewer has twenty-five years of experience! Truly, it is the “Champagne of Malt”! It is so effective at curbing drunkenness that the brewery is prepared to sell fourteen thousand gallons on a day’s notice.

Humbuggery aside, product analysis conducted by the Inland Revenue Department in 1910 suggests that the average strength of ale on the market hovered around 7.0 percent alcohol, whereas lager tended to come in between 3.5 and 4.5 percent. Given a similar production schedule, lager would be cheaper to produce than ale due to the smaller quantity of malt needed to produce the same volume of liquid. Additionally, any measure that might prevent the prohibition of alcohol was to be viewed by brewers as a good thing.

COMBINES AND ALLIANCES

After years of success, some brewers sought to leave their businesses behind to enjoy the benefits of the wealth that they had amassed. One critical problem they faced was how to move on from the brewery when they were effectively still governed by their founders. Two Toronto brewers, O’Keefe and Cosgrave, found themselves in court in the 1880s due to their reliance on the traditional business structure of partnership, which relied on the trust of individual partners and business associates.

Cosgrave & Sons was brought to court over a sales agreement. Patrick Cosgrave, the father, died in September 1881. A notice of a claim for $5,000 was served on the brewery in April 1882 based on a contract from years before. Fortunately for the brewery, the partnership (and therefore the obligation) was determined to have dissolved upon his death. However, the extended litigation proved the weakness of partnership as a way to run a large-scale brewery.

Eugene O’Keefe faced another sort of succession crisis that took him all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1889. His brewery was structured as a three-person partnership after he took on two young men to teach them the trade. Their deal provided that if anyone violated certain agreed terms, the others could ask him to leave the business and give up his share of the brewery’s value. One partner, Mead, decided that it would be a good idea to dip into the brewery’s accounts “for his own private purposes,” including lending money to his friends and relatives while “suppressing all such transactions and not making any proper record or proper entries of the same in the books of the said partnership.” Clearly, having sticky fingers was not good for the brewery or for the long-term plans of Eugene O’Keefe. He would carry on his brewing business for another two decades.

As the century was coming to an end and the province continued to expand, Ontario’s brewers were providing beer for a population that still remained, in large part, distinctly tied to the British empire, especially in the oldest communities. At the outset of the 1890s, the New York Times published a story entitled “A Quaint Canadian City” that noted the following about Kingston:

The similarity to the English extends quite noticeably to minor matters, even to eating and drinking. Pipes rather than cigars are smoked in the streets and public places. English relishes and sauces in great abundance are displayed upon the dining tables. Lager beer is wanting almost absolutely. I remember in all my travels, extending through hundreds of miles in Ontario, beginning at this place, to have seen the sign “lager beer” displayed only once. Light wines are rarely called for. Strong ales like Bass’s and stouts like Guinness’s abound.

These British ties were not just a matter of taste but also of business opportunity. British brewing investor groups sent representatives to North America to buy and consolidate brewing in the last years of the century. Both Labatt and Carling were attractive enough to receive offers just as they were setting up sales outlets in other provinces, the United States and even overseas. The two London brewers were sufficiently interested to listen on more than one occasion but eventually left offers on the table. They were convinced that their brewing empires were being undervalued.

Instead of selling out, the brewers of Ontario worked together to take on temperance, influence politicians, establish uniform pricing and develop other mutually profitable business practices. The Brewers’ and Maltsters’ Association of Ontario unsuccessfully took the provincial government to court over the duplication of licensing that Ontario’s law created when it was already federally required. The same association agreed to fixed prices in 1897, with eighteen brewers across the province participating in the plan.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the province’s brewers had come to enjoy as unregulated a marketplace as they ever would. Over the long reign of Queen Victoria, Ontario had transformed from a controlled society under the Family Compact to a relatively free one with a largely unregulated marketplace for beer and unprecedented prosperity in other aspects of society.