View from the Coast Trail

Exploring Point Reyes National Seashore

travel weary

just as I finally find lodging—

wisteria blossoms

—MATSUO BASHO, Knapsack Journey

View from the Coast Trail

Find joy in the sky, in the trees, in the flowers,

There are flowers everywhere

For those who want to see them.

—HENRI MATISSE, Matisse on Art

WITH 71,000 ACRES OF COASTAL HILLS, dense forests, pristine beaches, and 150 miles of hiking trails, Point Reyes National Seashore is a walkabout paradise only an hour and a half north of San Francisco by car or bus. This easy 27-mile walkabout over three days explores the central portion of the park. You’ll stay at lovely inns in Olema and Point Reyes Station and a hostel set deep in the park where you can commune with deer, bobcats, elk, and other residents of this enchanted wilderness. Stay an extra day or two and explore the esteros and miles of beautiful beaches.

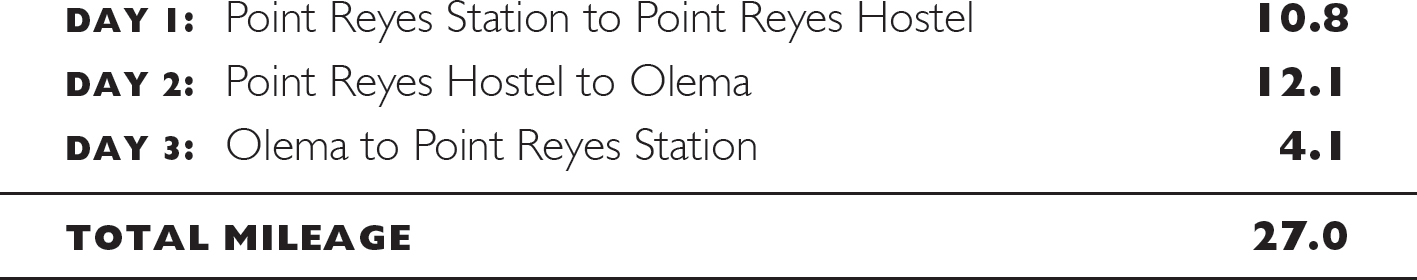

ITINERARY

Day 1: Point Reyes Station to Point Reyes Hostel

START THIS WALKABOUT at Point Reyes Station, a quiet village on the edge of the park with shops, taverns, and eateries. The Station House Café offers organic, locally sourced cuisine, and local musicians play on Sunday nights. You can kick up your heels and dance at the Old Western Saloon across the street.

Leaving Point Reyes Station, hike quiet country lanes along marshlands at the southern tip of Tomales Bay, and enter the park. At 1.4 miles, you reach Kule Loklo, meaning “Bear Valley,” a re-created Coast Miwok village. The lands of the Coast Miwok stretched from the Golden Gate north to Bodega Bay and east to Sonoma, what today is Marin and southern Sonoma Counties. Bands of the Olema tribe called Point Reyes home. At the center of Kule Loklo is the roundhouse, a communal and ceremonial structure 55 feet in diameter, built partially into the earth and supported by stout tree limbs. Acorn granaries, a sweat lodge, and conical houses made of redwood bark bring the village to life. A garden of native plants used by the Miwok for food, medicine, and basketry lies at the edge of the village.

The trail passes the park’s visitor center. Stop to learn about the history, geology, and ecology of the park. Then take the Bear Valley Trail 0.2 mile, turn on the Mount Wittenberg Trail, and enter an enchanted wilderness. The trail climbs 1,100 feet through forests of Douglas-fir, bay, live oaks, ferns, poison oak, and forget-me-nots. When we hiked in early June, grassy fields were still green and decorated with dandelions and blue-eyed grass. Songbirds serenaded. Two black-tailed does and a fawn crossed the trail 50 feet ahead of us. We all stopped to stare at each other before they delicately stepped into the underbrush and disappeared.

After 1.8 miles on Mount Wittenberg Trail, it reaches the ridge and Z Ranch Trail, the end of the uphill hiking for the day unless you would like to ascend another 0.2 mile to the highest point in the park, the top of Mount Wittenberg (1,407'). Our route turns south (left) along the crest on Z Ranch Trail 0.4 mile and joins Sky Trail for another 0.8 mile. Views of the Pacific open periodically through the dense woods.

Mount Wittenberg Trail

Take the Woodward Valley Trail, and descend 800 feet over the next 2 miles. Now the vast Pacific comes into full view. The great crescent shoreline of Drakes Bay arcs west all the way to Chimney Rock, a monolithic landmark at the tip of Point Reyes. The point was named by Spanish explorer Don Sebastian Vizcaíno on January 6, 1603. While sailing north from Monterey to explore the uncharted coastline, storms and heavy seas forced him to take shelter in Drakes Bay. Jutting south into the Pacific, the tall bluffs of the peninsula protected his ship from the westerly winds. It was the day of the Feast of the Three Kings, and out of gratitude, Vizcaíno named the point La Punta de Los Tres Reyes.

Turn right and follow the Coast Trail as it swings inland along Santa Maria Creek and back to the coastal bluffs above the Pacific. Inland, grassy hills climb sharply, and dense forests fill the creek canyons. The trail passes Coast Camp, one of four campgrounds in the park that can be reached on foot or by horse. The campgrounds fill up on summer weekends, but they are available on short notice most other days. Coast Camp lies in a sheltered meadow, protected from the ocean’s winds by grassy dunes. Only 1.9 miles from the road, it is an easy way for Bay Area residents to get their wilderness camping fix. Make reservations at recreation.gov, or call 877-444-6777.

Just beyond the campground, you reach the sea, 8.5 miles from your starting point. Wide beaches—Santa Maria, Limantour, and Drakes—arc 11 miles west to Chimney Rock, interrupted only by the narrow entrance to Estero de Limantour and Drakes Estero. Santa Maria Beach is a beautiful spot to stop for lunch. Steep, sandy cliffs stretch to the southeast, bordering the broad beach. Lush gardens of pale blue lupine, lavender asters, bright yellow mustard, and orange paintbrush, nourished by seeps in the vertical walls, descend 100 feet to the beach.

From Santa Maria Beach, hike 2 miles up Laguna Trail to the Point Reyes Hostel. After hiking the mountains and coastline of Point Reyes National Seashore for 10.8 miles, you have arrived at a wonderful destination for a day or two of relaxation and exploration.

Staying at Point Reyes Hostel

Hostelling International USA provides travelers with inexpensive lodging in amazing settings throughout California and the United States. Tucked in a small valley, 1.5 miles from the coast and surrounded by wooded hills, the Point Reyes Hostel has four private rooms and 36 bunk beds in men’s, women’s, and coed dormitories. The private rooms are nice for a couple or a family. They are often reserved months in advance, especially for summer weekends, but a dorm bed can usually be booked on fairly short notice. The hostel has a full communal kitchen, a living room, a library, and an outdoor sitting area.

Most guests arrive by car, and we had dropped off a cache of food before we started hiking. After cooking dinner, along with a very exuberant troop of Girl Scouts, we sat down with Nancy, the hostel host. She knew about Walkabout California and described herself as “a distance walker.” She had hiked 500 miles through Northern Spain on El Camino de Santiago, the Way of St. James. For 1,000 years, since medieval times, pilgrims have walked this route, and they continue to hike all or part of this UNESCO World Heritage Site today. We spent a few hours sharing stories about great inn-to-inn hikes in California and about her pilgrimage.

Descending to the coast

“Distance walker.” Doesn’t that describe most people throughout history? Only in recent centuries did horses and carriages become the common mode of transport for the privileged. Throughout human history, all others who strayed from their home villages were distance walkers. Modern distance walkers include Nancy and her fellow pilgrims on El Camino de Santiago, other European inn-to-inn hikers, backpackers, and all of us who have taken a walkabout in California.

There is something primal about traveling long distances on foot, but modern life makes it easy to forget that this is part of our nature. Hiking multiple days in an extraordinarily beautiful setting like Point Reyes without setting foot in a car connects us to the land and to an essential part of ourselves. As each day passes, the connections deepen.

Stay an extra day or two at the hostel, and explore Estero de Limantour and Drakes Estero, estuaries that reach deep into the peninsula. The long, narrow finger of Limantour Spit separates the esteros from Drakes Bay. Small tidal coves and marshes branch from the main estuaries and cut into the rolling hills. Coyote brush and small pines grow on the grassy hillsides. Trails travel along the inlets, and although Estero de Limantour is only 2 miles from the road, few hikers and mountain bikers venture into this part of the park.

Hiking along Estero de Limantour, we rounded a curve and spotted a group of tule elk, females with a very young calf. They grazed and lounged by a small tarn while mallards swam in the shallows and an egret stalked along the shore. Tule elk once roamed California’s hills and Central Valley, numbering half a million when Europeans arrived. They were hunted relentlessly and were thought to be extinct by the 1860s. But in 1874, a group of less than 30 was discovered in the marshes of southern San Joaquin Valley. A rancher, Henry Miller, protected them, and they started to make a comeback.

In the fall of 1978, 17 tule elk were released into a reserve at the north end of Point Reyes National Seashore. The population grew, and today it is estimated at 450. In 1998, 28 were moved to the Limantour Beach area.

Rutting and breeding season, August–October, is an exciting time to hike the reserve. Female hormones are pumping, and massive bulls, 7 feet long and 4–5 feet tall at the shoulders, sport coats of beige, dark-brown manes, tan rumps, and impressive racks. The males bugle to attract females and chase off other males to form harems of up to 30–50.

Fighting and breeding is exhausting work, and it is rare that a bull can dominate a second season. After the rut, males form bachelor groups, and in the winter, they drop their antlers. Females remain in groups throughout the year, except between mid-May and mid-June when pregnant cows separate from the group to give birth. They return after about three weeks with their newborn calves.

The roundhouse at Kule Loklo, a re-created Miwok village

Scholars believe Sir Francis Drake sailed the Golden Hinde into these waters on June 17, 1579, on his three-year voyage around the world. After rounding the tip of South America, he sacked Valparaiso and other Spanish coastal outposts. In March 1579 he captured the Spanish galleon Calafuego and stole enough gold, silver, and jewels to retire the debt of England. Sailing north as far as the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the entrance to the Puget Sound, he failed to find the Northwest Passage and returned south along the coast. His ship was leaking badly, and he feared discovery by Spanish ship captains who would have dearly loved to seek revenge for his plunder of their vessels. It is believed that he sailed into the shallow waters of Drakes Estero and stayed 36 days. His crew careened the ship, tipping the Hinde on her side, cleaning the hull, and repairing leaky seams.

Coast Miwok watched this amazing sight from the hills and then ventured down to greet the strangers. They met a party in exotic dress—sailors in cloth leggings and officers wearing stockings and shoes with buckles. The Miwok women wore deerskin skirts. The men, according to the ship’s chaplain, Francis Fletcher, were naked, “as though proud of the suit nature gave them.”

During the course of their five-week visit, the English ventured inland and found a land teeming with elk and deer. Black bears and grizzlies roamed the coastal mountains. The Miwok enjoyed a rich life. Archaeologists have found the remains of 139 Miwok villages in Point Reyes. Acorns were the main staple of the Miwok diet, but they also dined on harbor seals and sea lions; harvested oysters, clams, and mussels from the marshes along Tomales Bay; and netted salmon and steelhead seasonally from nearby streams.

Drake named the land Nova Albion because the cliffs along what is now Drakes Beach reminded him of his homeland. The Miwok must have stared in amusement and disbelief when he erected a sturdy post with a brass plate claiming this land for his queen, Elizabeth I.

Coast Miwok villagers gathered at night around a fire in the roundhouse while elders recited the tribe’s sacred stories. The visit by the strange men in the sailing ship must have become part of the narrative. A few other explorers made contact briefly with the Miwok, but it would be almost two centuries before the next extended visit by Europeans. This time they came to stay.

The San Carlos sailed into San Francisco Bay on August 5, 1775, dropping anchor off Sausalito. It was followed the next year by soldiers and priests, who established a mission and presidio in a village they would call Yerba Buena. The San Rafael mission was founded in 1817, but by this time old-world diseases had devastated the Coast Miwok. It is estimated that they numbered 5,000 at the time of first contact with Europeans. Over the 65 years following the establishment of Mission Dolores in San Francisco, 90% perished. Soldiers rounded them up for slave labor on the ranches and missions, and many fled to the protection of the Russians at Colony Ross.

Day 2: Point Reyes Hostel to Olema

A LIGHT EARLY-MORNING FOG LIFTED as we departed from the hostel, and a bobcat crossed the trail 100 yards away. Brownish red with a white underbelly and not much bigger than a house cat, it stopped to study us with a relaxed, almost drowsy expression and then ambled into the underbrush.

You can shave a mile off this day’s hike by returning to Santa Maria Beach on the Laguna Trail. If you take the slightly longer route on Coast Trail from the hostel, you can enjoy a long stroll along the beach. The tide was low when we walked the shore, and the sand was firm, perfect for hiking. We took off our boots and strolled barefoot. Two harbor seals surfaced just beyond the breaking waves and studied us. Ospreys soared overhead. One suddenly dove, snatched a fish in its talons, struggled to regain altitude, and flew inland with its catch. A line of California brown pelicans glided west just above the waves. Spotting a school of fish, they rose as a group and dove for lunch. Gulls flew in to pick up scraps in a chaotic feeding frenzy. We rested against a log. Although we had 12.1 miles to hike this day, with 16 hours of daylight there was no hurry.

The Coast Trail leaves the shore at Santa Maria Beach and follows the coastal bluffs 4.3 miles to Bear Valley Trail. It snakes in and out of creek drainages. Dense forests of 25-foot ceanothus with delicate lavender puffs of flowers at their tips descend the slopes to the creekbeds.

The long beaches and sand cliffs of the peninsula stretch to the west. Rocky bluffs and the rugged shoreline extend before you. To the south, the vast Pacific reaches the horizon, and on a clear day you can see the Farallon Islands jutting out of the ocean, 27 miles from shore. They were the peaks of the coastal range 10,000 years ago during the last ice age. When the glaciers receded, the coastline shifted 35 miles inland. Today the islands are home to an amazing abundance of sea life.

Francis Drake and his crew were the first Europeans to visit the Farallones, stopping to store seal meat for the voyage across the Pacific. Russian and American hunters, seeking precious pelts, wiped out the island’s fur seals by 1838. Northern elephant seals, prized for their blubber, met the same fate by the 1880s. To satisfy the insatiable appetite of San Francisco’s exploding population during and after the gold rush, hunters harvested eggs of the common murre, and their numbers plunged from a million to only a few thousand.

In 1909, President Teddy Roosevelt declared the Farallones a national wildlife refuge, and populations rebounded. The northern elephant seals returned in 1959, the northern fur seals in 1996. The islands now constitute the largest seabird rookery in the continental United States, with 350,000 birds, including a thriving population of common murres.

Hiking the Coast Trail

The islands perch on the edge of the continental shelf, where the ocean floor plunges 6,000 feet. The cold waters of the California current flow south from British Columbia, causing upwellings and enormous blooms of plant plankton in the spring. Krill eat the plankton, and birds, fish, and whales feast on the krill. Migrating dolphins and humpback, gray, and blue whales stop to feed in the nutrient-rich waters. From the Coast Trail you can spot gray whales migrating south in the fall, spouting far out to sea. They return in late winter and early spring for the journey north with their calves, this time much closer to shore.

The trail passes three small beaches that are fun to explore: Sculptured, Secret, and Kelham. It reaches the Bear Valley Trail at 7.1 miles from the hostel. A short hike to Arch Rock was a popular side trip from this junction until tragedy struck in March 2015. Seven hikers were atop the popular coast overlook when a 50-foot section of the cliff suddenly collapsed with a thunderous crash. Five scrambled and escaped unharmed, but two were hurled 75 feet to the beach, where one perished and one was seriously injured.

The Bear Valley Trail turns inland. It is a broad path that travels 4 miles through dense forest back to the visitor center, gradually ascending 2.4 miles to Divide Meadow, and then gradually descending to the trailhead.

Walk down the visitor center road to Bear Valley Road, turn right and hike a mile to Olema where there are several inns and B&Bs. Olema has two good restaurants, the Farm House and Sir and Star at the Olema, both near the intersection of CA 1 and Sir Francis Drake Boulevard. We spent a leisurely evening at the Farm House dining on fresh local oysters and succulent pan-seared seabass and horseradish-crusted cod, a nice way to end a beautiful day’s hike.

Day 3: Olema to Point Reyes Station

THE FINAL LEG OF THIS WALKABOUT is only 4.1 miles. Return to the visitor center area along Bear Valley Road, and take the trail to Kule Loklo. Coast Miwok people continue to live in their historical land: the cities of Marin County, Bodega Bay, and around Tomales Bay. Betty Goerke, author of Chief Marin, writes of a gathering held here in 2001. Two hundred tribal members and supporters crowded into the roundhouse to celebrate the tribe’s recent recognition by the federal government after years of struggle.

Your trail continues back to Point Reyes Station. You may want to stop for a while in the Coast Miwok village. It takes on a deeper meaning after you have immersed yourself in this land the native peoples called home.

Sitting in the Miwok village, I felt gratitude for their stewardship over thousands of years and now to all the recent citizens who worked to preserve and maintain this amazing wilderness that is only a short trip from the urban centers of the Bay Area. It is a land waiting to be explored. There is no better way than a long walkabout.

THE ROUTE

All mileages listed for a given day are cumulative.

Day 1: Point Reyes Station to Point Reyes Hostel

Walk south out of Point Reyes Station along CA 1. There is a broad shoulder, and traffic moves slowly on this stretch. Turn right on Sir Francis Drake Boulevard. Turn left on Bear Valley Road and go 0.3 mile. Turn right on the unmarked trail after the Limantour Road intersection. The Kule Loklo Trail takes you past a re-created Coast Miwok village and to the park’s visitor center. 2.8 miles

Take the Bear Valley Trail 0.2 mile from the visitor center, and turn right on Mount Wittenberg Trail to Z Ranch Trail. 4.8 miles

Take Z Ranch Trail south (left) to Sky Trail to Woodward Valley Trail. 6.0 miles

Turn right on Woodward Valley Trail to the Coast Trail. 8.0 miles

Turn right on the Coast Trail to Laguna Trail. 8.8 miles

Turn right to Point Reyes Hostel.

total miles 10.8

Day 2: Point Reyes Hostel to Olema

You can cut a mile off this leg by returning to Santa Maria Beach on Laguna Trail, but you will miss a nice long hike on the shore.

Leaving the hostel, take the Coast Trail to the beach. 1.6 miles

Continue on the trail, or walk along the beach. The Coast Trail turns inland along the bluffs at Santa Maria Beach. 2.8 miles

Continue on the Coast Trail to Bear Valley Trail. 7.1 miles

Turn inland on Bear Valley Trail to the visitor center. 11.1 miles

Walk down from the visitor center to Bear Valley Road, and turn right to Olema.

total miles 12.1

Day 3: Olema to Point Reyes Station

Return to the visitor center area on Bear Valley Road. 1.0 mile

Take the Kule Loklo Trail back to Bear Valley Road. 2.7 miles

Turn left on Bear Valley Road to Sir Francis Drake Boulevard 3.0 miles.

Turn right on Sir Francis Drake Boulevard and left along the shoulder of CA 1 into Point Reyes Station.

total miles 4.1

TRANSPORTATION

Public Transportation from San Francisco

TRAVELING TO POINT REYES by public transit from almost anywhere in the Bay Area is efficient and inexpensive. Visit 511.org for easy trip planning.

From San Francisco, take BART to the Civic Center Station (see bart.gov). Walk a few blocks down Market Street to Seventh Street. Take Golden Gate Transit Bus 101 to the San Rafael Transit Center. The trip takes approximately 1 hour and costs $7. Schedules and other information are available at goldengatetransit.org. Take the West Marin Stagecoach 68 from the San Rafael Transit Center to Olema or downtown Point Reyes Station. This trip takes approximately 1 hour and costs $2. More information and schedules are available at marintransit.org.

Flying into the Bay Area

FROM SFO TAKE BART to the Civic Center Station ($8.95) and follow the public transportation directions on the previous page. From the Oakland International Airport take Oakland Airport BART to Oakland Coliseum Station. Take BART to the San Francisco Civic Center Station, and follow the public transportation directions on the previous page. The trip takes about 35 minutes and costs $10.20.

Coast Camp, one of four campgrounds at Point Reyes National Seashore

MAPS

THE POINT REYES NATIONAL SEASHORE WEBSITE (nps.gov/pore) provides a free downloadable map. This map is also available at the park’s visitor center. Wilderness Press publishes an excellent map of the park, Point Reyes National Seashore and West Marin Parklands, for $7.46; visit wildernesspress.com to purchase. Point Reyes National Seashore for $10.95 by Tom Harrison Maps is also excellent; visit tomharrisonmaps.com.

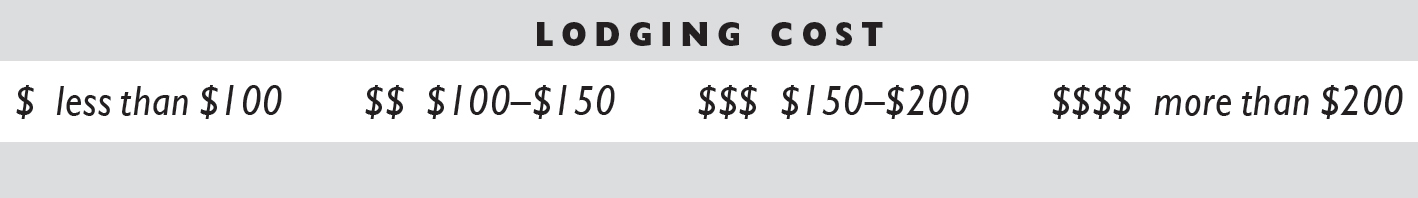

PLACES TO STAY

Point Reyes Station

POINT REYES SCHOOLHOUSE $$$$ • 11559 CA 1 • 3 blocks north of the town center • 415-663-1166 • pointreyesschoolhouse.com

POINT REYES STATION INN $$–$$$$ • 11591 CA 1 • 3 blocks north of the town center • 415-663-9372 • pointreyesstationinn.com

Point Reyes National Seashore

POINT REYES HOSTEL $–$$ • 1390 Limantour Spit Road • 415-663-8811 • hiusa.org • Pack in your food or drop it off in advance.

Olema

OLEMA HOUSE (formerly The Lodge at Point Reyes) $$$$ • 10021 CA 1 • 415-663-9000 • olemahouse.com

ROBIN’S RETREAT AND HONEYBEE COTTAGE $$–$$$ • 10210 Shoreline Hwy. • 415-663-1288 • robinsretreat.com

INN AT ROUNDSTONE FARM $$ • 9940 Sir Francis Drake Blvd. • 415-663-1020 • roundstonefarm.com

BEAR VALLEY COTTAGE $$$$ • 88 Bear Valley Road • 415-663-1777 • bearvalleycottage.com • 15% discount for those hiking in.