• CORE

Sitting in front of his holographic display—sole illumination in the deserted lab—Alex recalled George Hutton’s performance at the celebration, earlier in the evening, reciting Maori legends to the tired but happy engineers by firelight. Especially appropriate had been the tale of Rangi-rua’s, speaking as it did of fresh hope, snatched from the very gates of hell.

Later, though, Alex found himself drawn back to the underground laboratory. All the machinery, so busy earlier in the day, now lay dark and dormant save under this pool of light, which spilled long shadows onto the nearby limestone walls.

Rangi’s legend had touched Alex, all right. It might apply to his present state of mind.

Don’t look back. Pay attention to what’s in front of you.

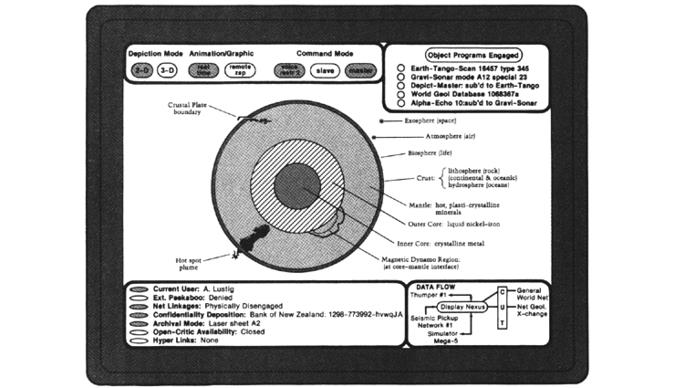

Right now what lay before him was a depiction of the planet, in cutaway view. A globe sliced like an apple, revealing peel and pulp, stem and core.

And seeds, Alex thought, completing the metaphor.

The eye couldn’t make out Earth’s slight deviations from a sphere. Mountain ranges and ocean trenches—exaggerated on commercial globes—were mere dewy ripples on this true-scale representation. So thin was the film of water and air compared to the vast interior.

Inside that membrane, concentric shells of brown and red and pink denoted countless subterranean temperatures and compositions. With a word, or by touching the holo’s controls, Alex could zoom through mantle and core, following rocky striations and myriad charted rivers of magma.

Okay, George, he thought. Here’s a pakeha allegory for you. We’ll start by cutting a hole straight through the Earth.

From the surface of the globe, he caused a narrow line to stab inward, through the colored layers. Drill a tunnel, straight as a laser, with mirror-smooth walls. Cover both ends and drop a ball inside.

It was an exercise known to generations of physics students, illustrating certain points about gravity and momentum. But Alex played the scenario in earnest.

Assuming that inertial and gravitational mass balance, as they tend to do, anything dropped at Earth’s surface accelerates nine point eight meters per second, each second.

His fingers stroked knobs, releasing a blue dot from the outer rim. It fell slowly at first, even with the time rate magnified. A millimeter here stood for an awful lot of territory in the real world.

But after the ball falls a good distance, acceleration has changed.

In 1687, Isaac Newton took several score pages to prove what smug sophomores now demonstrated on a single sheet—ah, but Newton did it first!—that only the spherical portion “below” a falling object continues to apply net gravity, until acceleration stops altogether as the ball hurtles through the center at a whizzing ten kilometers per second.

It can’t fall any farther than that. Now it’s streaking upward.

(Answer a riddle—where is it you can continue in a straight line, yet change directions at the same time?)

Now more and more mass accumulates “below” the rising ball. Gravity clings, draining kinetic energy. Speed slackens till at last—neglecting friction, coriolis effects, and a thousand other things—our ball lightly bumps the door at the other end.

Then it falls again, hurtling once more past sluggish, plasti-crystal mantle layers, past the molten dynamo of the core, plummeting then climbing till finally it arrives “home” once more, where it began.

Numbers and charts floated near the giant globe, telling Alex the round trip would take a little over eighty minutes. Not quite the schoolboy perfect answer, but then schoolboys don’t have to compensate for a real planet’s varying density.

Next came the neat trick. The same would be true of a tunnel cut through the Earth at any angle! Say, forty-five degrees. Or one drilled from Los Angeles to New York, barely skimming the magma. Each round trip took about eighty minutes—the period of a pendulum with the same span as the Earth.

It’s also the period of a circular orbit, skimming just above the clouds.

Alex soon had the cutaway pulsing with blue dots, each falling at a different angle, swiftly along the longer paths, slowly along shorter ones. Besides straight lines there were also ellipses, and many-petaled flower trajectories. Still, to a regular rhythm, they all recombined at the same point on the surface, labeled PERU.

Of course, things change when you include Earth’s rotation … and the pseudo-friction of a hot object pushing against material around it …

Alex was procrastinating. These simulations were from his first days in New Zealand. There were better ones.

His hands hesitated. The palms were still blotchy from skin grafts after that helium explosion debacle. Ironically, they hadn’t trembled half as much, then, as after today’s astonishing news.

Alex wiped away all the whirling dots and called another orbit from memory cache. This figure—traced in bright purple—was smaller than the others—a truncated ellipse subtly twisted from Euclidean perfection by irregularities in the densely-packed core. It didn’t approach Peru anymore.

This was no theoretical simulation. When their first gravity scans had shown the thing’s awful shadow, horror had mixed with terrible pride.

It didn’t evaporate immediately, he had realized. I was right about that.

It was awful news. And yet, who in his position wouldn’t feel heady emotions, seeing his own handiwork still throbbing, thousands of miles below the fragile crust?

It lived. He had found his monster.

But then it surprised him yet again.

After Pedro Manella’s headlines had made him the world’s latest celebrated bad-boy, it naturally came as a relief when the World Court dismissed all charges on a technicality of the Anti-Secrecy Laws. Alex was seen as the dupe of unscrupulous generals, more fool than villain.

It might have been better had they jailed and reviled him. Then, at least, people in authority might have listened to him. As it was, his peers dismissed his topological arguments as “bizarre, overly complex inventions.” Worse, special interest groups on the World Data Net made him a gossip centerpiece overnight.

“… classic symptoms of guilt abstraction, used by the subject to disguise early childhood traumas …” one correspondent from Peking had written. Another in Djakarta commented, “Lustig’s absurd hints that Hawking’s dissipation model might be wrong mesh perfectly with the shame and humiliation he must have felt after Iquitos …”

Alex wished his Net clipping service were less efficient, sparing him all the amateur psychoanalyses. Still, he had made himself read them because of something his grandmother once told him.

A hallmark of sanity, Alex, is the courage to face even unpleasant points of view.

How ironic then. Here he was, vindicated in a way he could never have imagined. He now had proof positive that the standard model of micro black holes was flawed … that he had been on the right path with his own theories.

Right and wrong, in the best combination of ways.

Then why can’t I leave this cave? he wondered. Why do I feel it isn’t over yet?

“Hey, you stupid pakeha bastard!” A booming voice ricocheted off the limestone walls. “Lustig! You promised to get drunk with us tonight! Tama meamea, is this any way to celebrate?”

Alex had the misfortune to be looking up when George Hutton switched on the lights. His world, formerly confined to the dim pool of the holo tank, suddenly expanded to fill the cavern-lab Hutton’s wealth had carved under the ancient rock.

Alex’s blinking eyes focused first on the thumper, a shining rod two meters in diameter and more than ten long, caged to a universal bearing in a bowl excavation larger than some lunar craters. It resembled the work of some mad telescope maker who had neglected to make his instrument hollow, crafting it, instead, of perfect, superconducting crystal.

The gleaming cylinder pointed a few degrees off vertical, just as they had left it after that final bracketing run. Banks of instruments surrounded the gravity antenna, along with ankle-deep layers of paper, shredded by the ecstatic technicians when the good news had finally been confirmed.

Beyond the thumper, a flight of steps led upward to where George Hutton stood, waving a bottle and grinning. “You disappoint me, fellow,” the broad-shouldered billionaire said, sauntering downstairs unevenly. “I planned getting you so pissed you’d spend the night with my cousin’s poaka of a daughter.”

Alex smiled. If that was what George wanted him to do, he was bound to comply. Without Hutton’s influence he’d never have been able to sneak into New Zealand incognito. There’d have been no long hard search through the awesome complexity of the Earth’s interior, improvising and inventing new technologies to hunt a minuscule monster. Worst of all, Alex might have gone to his grave never knowing what his creation was up to down below—if it was quietly dissipating or, perhaps, proceeding at a leisurely pace to devour the world.

At first, sighting it several days ago on a graviscan display had seemed to confirm their worst fears. The nightmare, reified.

Then, to everyone’s relief and astonishment, hard data seemed to point another way. Apparently the thing was dying … evaporating more mass and energy into the Earth’s interior than it sucked in through its narrow event horizon. True, it was thinning much more slowly than the obsolete standard models predicted. But in a few months, nevertheless, it would be no more!

I really should celebrate with the others, Alex thought. I should put aside my last suspicions, crawl into any bottle George offers me, and find out what a poaka is.

Alex tried to stand, but found he couldn’t move. His eyes were drawn back to the purple dot, circling the innermost colored layer.

He felt a large presence nearby. George.

“What is it, friend? You haven’t found an error, have you? It is …”

Alex caught Hutton’s sudden concern, “Oh, it’s dissipating all right. And now …” He paused. “Now I think I know why. Here, take a look.”

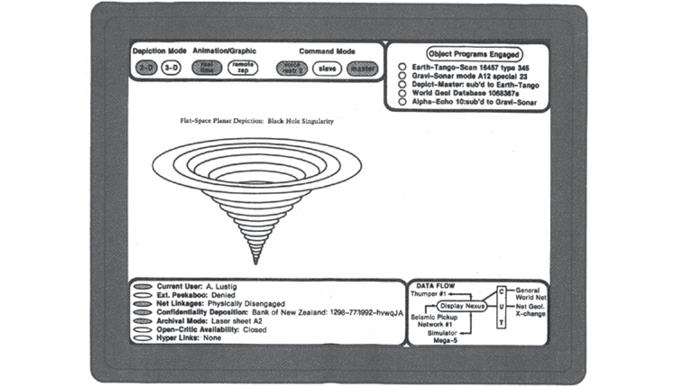

With a word he banished the model of the Earth, replacing it with a schematic drawn in lambent blue. Reddish sparkles flashed at the rim of the object now centered in the tank. They swept toward a central point like beads caught in water, swirling down a drain.

“This is what I thought I was making, back when His Excellency persuaded me to build a singularity for the Iquitos plant. A standard Kerr-Prestwich black hole.”

Hutton took a stool next to Alex and watched with those deceptive brown eyes. One might guess he was a simple laborer, not one of Australasia’s wealthiest men.

The image in the tank looked like a rubber sheet that had been stretched taut and heated, and then had a small, heavy weight dropped onto it. The resulting funnel had finite width and depth in the display, but both men knew that the real thing—the hole in space it represented—had no bottom at all. The reddish dots represented bits of matter drawn in by gravitational tides, caught in a swirling disk. The disk brightened as more matter fell, until a ring of fierce brightness burned near the funnel’s lip. Below this came a sudden cutoff within which only pitch blackness reigned.

Nothing escapes from inside a black hole’s event horizon. At least, there’s no direct escape.

Alex glanced at George. “Cosmologists say many singularities like this must have been created when the universe began. If so, only the biggest survive today. Smaller ones evaporated long ago, as predicted in the 1970s by Stephen Hawking. A simple singularity—even with charge and rotation—has to be extremely heavy to be stable … to pull in matter faster than it’s lost by vacuum emission.”

He pointed to the outskirts of the depression, where bright white pinpoints flashed independently of the hot ring of accreting material.

“Some distance out, the tight stress-energy of infolding gravity causes spontaneous pair production … ripping particle-antiparticle twins—an electron and a positron, for instance—out of the vacuum itself. It isn’t exactly getting something from nothing, since each little genesis costs the singularity some field energy. And that’s debited to its mass.”

The sparkles formed a halo of brilliance—creation in the raw.

“Generally, one newborn particle falls inward and the other escapes, resulting in a steady weight loss. A tiny hole like this one can’t pull in new matter fast enough to make up the difference. To prevent dissipation you have to feed it.”

“As you did with your ion gun, in Peru.”

“Right. It cost a lot of power to make the singularity in the first place, even using my special cavitron recipe. It took even more to keep the thing levitated and fed. But the accretion disk gave off incredible heat.” Alex felt briefly wistful. “Even the prototype was cheaper, more efficient than hydro power.”

“But then you started having doubts,” George prompted.

“Yeah. The system was too efficient, you see. It didn’t need much feeding at all. So I toyed with some crazy notions … and came up with this.”

A new schematic replaced the funnel. Now it was as if a heavy loop of wire had sunk into the rubber sheet. Still unfathomably deep, the depression now circled on itself.

Again, reddish bits of matter swept into the cavity, heating as they fell. And again, sparkles told of vacuum pair production—the singularity repaying mass into space.

“This is something people talked about even back in TwenCen,” Alex said. “It’s a cosmic string.”

“I’ve heard of them.” George’s dark features showed fascination. “They’re like black holes. Also supposed to be left over from that explosion you pakeha say started everything—the Big Bang.”

“Uh-huh. They aren’t truly funnel-things drawn in circles, of course. There’s a limit to how well you can represent …” Alex sighed. “It’s hard to describe this without math.”

“I know math,” George grumbled.

“Mm, yes. Excuse me, George, but the tensors you use, searching for deep methane, wouldn’t help a lot with this.”

“Maybe I understand more’n you think, white boy.” Hutton’s dialect seemed to thicken for a moment. “Like I can see what your cosmic string’s got that black holes don’t. Holes got no dimensions deep inside. But strings have length.”

George Hutton kept doing this—play-acting the “distracted businessman,” or “ignorant native boy,” then coming back at you when your guard was down. Alex accepted the rebuke.

“Good enough. Only strings, just like black holes, are unstable. They dissipate too, in a colorful way.”

At a spoken word, a new display formed.

The rubber sheet was gone. Now they watched a loop in space, glowing red from infalling matter, and white from a halo-fringe of new particles, showering into space. Inflow and outgo.

“Now I’ll set the simulation in motion, stretching time a hundred-million-fold.”

The loop began undulating, turning, whirling.

“One early prediction was that strings would vibrate incredibly fast, influenced by gravitational or magnetic …”

Two sides collided in a flash, and suddenly a pair of smaller loops replaced the single large one. They throbbed even faster than before.

“Some astronomers claim to see signs of gigantic cosmic strings in deep space. Perhaps strings even triggered the formation of galaxies, long ago. If so, the giant ones survived because their loops cross only every few billion years. Smaller, quicker strings cut themselves to bits …”

As he spoke, both little loops made lopsided figure eights and broke into four tinier ones, vibrating madly. Each of these soon divided again. And so on. As they multiplied, their size diminished and brightness grew—bound for annihilation.

“So,” George surmised. “Small ones still aren’t dangerous.”

Alex nodded. “A simple, chaotic string like this couldn’t explain the power curves at Iquitos. So I went back to the original cavitron equations, fiddled around with Jones-Witten theory a bit, and came up with something new.

“This is what I thought I’d made, just before Pedro Manella set off his damned riot.”

The tiny loops had disappeared in a blare of brilliance. Alex uttered a brief command, and a new object appeared. “I call this a tuned string.”

Again, a lambent loop pulsed in space, surrounded by white sparks of particle creation. Only this time the string didn’t twist and gyre chaotically. Regular patterns rippled round its rim. Each time an indentation seemed about to touch another portion, the rhythm yanked it back again. The loop hung on, safe from self-destruction. Meanwhile, matter continued flowing in from all sides.

Visibly, it grew.

“Your monster. I remember from when you first arrived. I may be drunk, Lustig, but not so I’d forget this terrible taniwha.”

Watching the undulations, Alex felt the same mixed rapture and loathing as when he’d first realized such things were possible … when he first suspected he had made something this biblically terrible, and beautiful.

“It creates its own self-repulsion,” he said softly, “exploiting second- and third-order gravities. We should have suspected, since cosmic strings are superconducting—”

George Hutton interrupted, slapping a meaty hand onto Alex’s shoulder. “That’s fine. But today we proved you didn’t make such a thing. We sent waves into the Earth, and echoes show the thing’s dissipating. It’s dying. Your string was out of tune!”

Alex said nothing. George looked at him. “I don’t like your silence. Reassure me again. The damned thing is for sure dying, right?”

Alex spread his hands. “Bloody hell, George. After all my mistakes, I’d only trust experimental evidence, and you saw the results today.” He gestured toward the mighty thumper. “It’s your equipment. You tell me.”

“It’s dying.” George said, flat out. Confident.

“Yes, it’s dying. Thank heaven.”

For another minute the two men sat silently.

“Then what’s your problem?” Hutton finally asked. “What’s eating you?”

Alex frowned. He thumbed a control, and once again a cutaway view of the Earth took shape. Again, the dot representing his Iquitos singularity traced lazy precessions among veins of superheated metal and viscous, molten rock.

“It’s the damn thing’s orbit.” Equations filed by. Complex graphs loomed and receded.

“What about its orbit?” George seemed transfixed, still holding the bottle in one hand, swaying slightly as the dot rose and fell, rose and fell.

Alex shook his head. “I’ve allowed for every density variation on your seismic maps. I’ve accounted for every field source that could influence its trajectory. And still there’s this deviation.”

“Deviation?” Alex sensed Hutton turn to look at him again.

“Another influence is diverting it. I think I’ve got a rough idea of the mass involved.… ”

The bigger man swung Alex around bodily. The Maori’s right hand gripped his shoulder. All signs of intoxication were gone from Hutton’s face as he bent to meet Alex’s eyes.

“What are you telling me? Explain!”

“I think …” Alex couldn’t help it. As if drawn physically, he turned to look back at the image in the tank.

“I think something else is down there.”

In the ensuing silence, they could hear the drip-drip of mineral-rich water, somewhere deeper in the cave. The rhythm seemed much steadier than Alex’s heartbeat. George Hutton looked at the whiskey bottle. With a sigh, he put it down. “I’ll get my men.”

As his footsteps receded, Alex felt the weight of the mountain around him once more, all alone.

In ages past, men and women kept foretelling the end of the world. Calamity seemed never farther than the next earthquake or failed harvest. And each dire happening, from tempest to barbarian invasion, was explained as wrathful punishment from heaven.

Eventually, humanity began accepting more of the credit, or blame, for impending Armageddon. Between the world wars, for instance, novelists prophesied annihilation by poison gas. Later it was assumed we’d blow ourselves to hell with nuclear weapons. Horrible new diseases and other biological scourges terrified populations during the Helvetian struggle. And of course, our burgeoning human population fostered countless dread specters of mass starvation.

Apocalypses, apparently, are subject to fashion like everything else. What terrifies one generation can seem obsolete and trivial to the next. Take our modern attitude toward war. Most anthropologists now think this activity was based originally on theft and rape—perhaps rewarding enterprises for some caveman or Viking, but no longer either sexy or profitable in the context of nuclear holocaust! Today, we look back on large-scale warfare as an essentially silly enterprise.

As for starvation, we surely have seen some appalling local episodes. Half the world’s cropland has been lost, and more is threatened. Still, the “great die-back” everyone talks about always seems to lie a decade or so in the future, perpetually deferred. Innovations like self-fertilizing rice and super-mantises help us scrape by each near-catastrophe just in the nick of time. Likewise, due to changing life-styles, few today can bear the thought of eating the flesh of a fellow mammal. Putting moral or health reasons aside, this shift in habits has freed millions of tons of grain, which once went into inefficient production of red meat.

Has the Apocalypse vanished, then? Certainly not. It’s no longer the hoary Four Horsemen of our ancestors that threaten us, but new dangers, far worse in the long run. The by-products of human shortsightedness and greed.

Other generations perceived a plethora of swords hanging over their heads. But generally what they feared were shadows, for neither they nor their gods could actually end the world. Fate might reap an individual, or a family, or even a whole nation, but not the entire world. Not then.

We, in the mid-twenty-first century, are the first to look up at a sword we ourselves have forged, and know, with absolute certainty, it is real.…

—From The Transparent Hand, Doubleday Books, edition 4.7 (2035).

[hyper access code 1-tTRAN-777-97-9945-29A.]