3

Uniting the World’s Workers

REBALANCING THE INTERNATIONAL ORDER TOWARD LABOR

The town of Amiens was not Delphine’s image of France. Television access was intermittent during her childhood in Haiti. She would crowd into her neighbors’ creaking shack every few evenings to watch TV. The images of Parisian cafes or of chic life along the Côte d’Azur brightened her bleak life. Then the terrible earthquake came and her family, like many others, was forced to head to Port-au-Prince. There, a television was more a spectacle for a crowd than a daily escape.

Delphine’s childhood ended when she was twelve. Work was hard, responsibilities exhausting, and fear of starvation never far away in that harsh and overcrowded city. But those TV images of beautiful women smoking cigarettes, of men more likely to carry flowers than guns, of fresh-baked croissants—they never left her.

On the way home from the trash pile she picked through each day, she met Fabiola. Fabiola was something of a queen in the camp. She spoke perfect French, worked in the French-speaking hotel downtown, and was feared but respected by others in the camp. But Delphine wasn’t afraid of her. All she wanted was to sit every evening for fifteen minutes at Fabiola’s feet and practice her French. She knew she would one day be able to match the tones of those actresses on TV. One day she would greet a stranger with a perfect “bonjour” and they would think she was from Africa, not Haiti.

So when French recruiting agents began combing through her camp for the few whose French they could understand, Delphine pushed her way to the front of the line. The agents warned her of the difficulties and dangers that awaited her, but they all seemed nothing in comparison to what she had already gone through. They explained that she would be able to take home only a few thousand euros a year after her basic rations and tiny room were paid for. A few thousand euros? This was more than Delphine had earned in the last decade.

Amiens was not Paris, though. Rustic charm it had aplenty, but few people resembled the glamorous characters in Plus belle la vie, her favorite soap opera. Delphine tried to avoid the temptations of downtown in any case: in one night there, she could easily lose money she knew would buy her mother and brother back home a toilet, a house, a business. The reborn factory on the town’s edge was most of her life. Her taciturn host Fabian would drive her and the three other Haitians his family hosted out to the factory each morning.

The arrival of the Haitians meant almost as much to Fabian as it meant to them. He was a manager in the factory now, almost twenty years after he had been laid off from his job when the factory closed. Labor costs had been too high to employ workers like him at prevailing French wages, and the work had moved to Vietnam. Fabian had always hated migrants and voted for the Front National. When the reformist government of Emmanuel Macron adopted what he was sure would be a disastrous new migration policy, he had no way to make ends meet other than giving a go to sponsoring migrants. The €15,000 his family made from hosting the Haitians, after paying to put up the small and cramped house on the edge of their family’s lot and give them a meal every night, finally made up for the income he had lost when he switched to waiting tables. The migrants had even given him advice to help the restaurant where he waited tables improve its cuisine. Plantains added a smooth sweetness to the restaurant’s signature duck pâté and helped distinguish the restaurant from the standard regional cuisine.

But what really changed his life was his new job at the factory. The fresh supply of Haitian labor had persuaded the entrepreneurs who had bought up his old workplace to reopen it, and Fabian’s familiarity with the Haitians made him a perfect manager. It was also a safer job, a cleaner job, a job with more dignity, power, and respect. He had hated so many Muslim immigrants who he had felt were changing the culture of the country, but he came to have a paternalistic and condescending love for the Haitians he managed and hosted. Their love of France, their gratitude, their struggles to adapt and learn … they all melted Fabian’s jaded heart.

Fabian was therefore much sadder than he let on when Delphine decided, after ten years, to return home. Having earned enough in those years to finally open the hotel that Fabiola had always dreamed about, she was resolved to build a piece of France in the Caribbean. She had learned so much and was glad for the trips she had been able to take, but France was not her home and the opportunities opening in Haiti these days made it the right place for her.

Globalization has transformed many aspects of society and yet left other parts virtually untouched. Foreign products surround us. Consider the goods and services most Americans use: our clothes are made in Vietnam, our mortgages owned by Chinese companies, our luxuries imported from Europe, and our cars made in Latin America. Foreign tourists swarm our cities, and talented foreign workers and immigrants populate our start-ups, banks, and universities. Globalization has increased foreign trade, capital flows, tourism, and the migration of highly skilled workers.

Yet, for all the controversies about refugees and (in the United States) illegal immigration, migration of people with ordinary skills proceeds at a trickle. From the standpoint of economic theory, this “migration imbalance,” as we will call it, is puzzling. Economists believe that global wealth increases when all factors of production—goods, services, capital, labor—are allowed to flow across borders to the locations where they can be most efficiently employed. What is special about migration (a term that we will henceforth use to refer to migration of ordinary workers rather than highly skilled workers and tourists)?

The Origins of Free Trade

Long-distance movements of goods and tools have been a feature of human civilization since the beginning of agriculture. The Mediterranean trade was central to Athenian, Carthaginian, and Roman development. Mohammad was a trader and the trading routes of the Muslim world and on to Asia via the Silk Road helped maintain the light of civilization through the Middle Ages in the West.1

Mass migrations were also a feature of early history. Many of the great empires were established and later destroyed by nomadic tribes that flooded from the North Asian steppe southward, westward, and eastward. The Germans, the Huns, the Mongols, the Turks, and other groups moved, often violently, through established civilizations to find, conquer, and eventually settle more fertile and civilized lands, only to be attacked by the next wave of nomads.

The advent of long-range sea power in Europe in the fifteenth century brought this era to an end. By this time, most of the planet was occupied by sedentary agricultural societies. Europeans discovered sea and land routes to most of the world and colonized regions viewed as having weak or “inferior” civilizations. Trade across settled homelands, and plunder of colonies, expanded as the skill of navigators improved. Trade became a leading question of state.

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the dominant philosophy uniting colonialism and trade was mercantilism. Mercantilists believed that sovereigns should try to sell goods abroad while importing as little as possible, allowing them to accumulate capital, ideally in the form of hard currency. To stimulate wealth accumulation, mercantilists advocated state control of the economy, including subsidies for exports and taxes on imports. Some mercantilists, such as Robinson Crusoe author Daniel Defoe, advocated unrestricted immigration, hoping that migrants would compete with native workers to drive down wages.2 For the same reason, they were wary of emigration, which reduced the size of the national labor force and hence its ability to produce exports.3

Mercantilism reflected the interests of the ruling classes of the time.4 Mercantilist policies burdened ordinary people but generated savings for the state that rulers could use to achieve military supremacy and maintain public order. Those rulers saw their populations as resources to be exploited rather than citizens whom they served.

During the late eighteenth century, many of the Radical thinkers we discussed in earlier chapters developed a new theory of trade. Bentham, Smith, and David Hume shifted the focus of economic analysis away from the interest of sovereigns in accumulating wealth and toward the desire of ordinary people to enjoy prosperity. They believed that economic freedom of many kinds (to exchange across borders, to borrow and lend, to repurpose and sell land and other capital, etc.) was critical to maximizing the total welfare that a nation’s economy could deliver to its citizens. With their focus on the benefits of markets, they embraced free international trade and opposed monopolies and state-imposed restrictions of domestic markets like price controls. The Radical Market of the time was one that extended beyond the borders of nations.

Before Migration Mattered

While the early Radicals passionately advocated free trade, they said little about migration.5 This might seem odd: the logic of free migration and free trade is the same, namely, that the expansion of economic openness generates wealth for nearly everyone. Some of these thinkers also mentioned, in passing, that they supported the free movement of people, not just goods. For example, both Smith and David Ricardo argued for free mobility of workers from the countryside to the city and across occupations, and in an offhand way remarked that the same should apply across borders. They also emphasized the importance of the free movement of ideas. Yet free trade overwhelmingly dominated free migration in their thought.

One reason for the emphasis of trade over migration was that in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the gains from trade were far more important than the gains from migration. The reason is that while different nations went through periods of relative prosperity and decline, persistent differences in mass living standards across countries were unknown until the late nineteenth century. Even the most extreme gaps, such as between China and the United Kingdom, were only a factor of 3. This contrasts with the 10 to 1 gap that opened up by the 1950s.6

A natural way to measure inequality is to determine the percentage by which an average individual’s income could be increased if income were equally distributed.7 For example, suppose there are two individuals, one with income of $1 million and one with income of $1,000. If we equalized income, the first person’s income would fall to $500,500, or nearly 50%. The second person’s income would rise to $500,500, an increase of 500 times, or 50,000%. Thus, equalizing incomes would cause a large average percentage increase in income of slightly less than 24,975%.8 By contrast, this measure of inequality would be 0 for a society in which everyone has equal income. The higher the number, the more unequal the society.

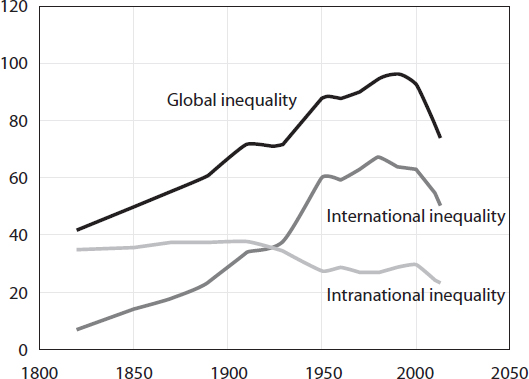

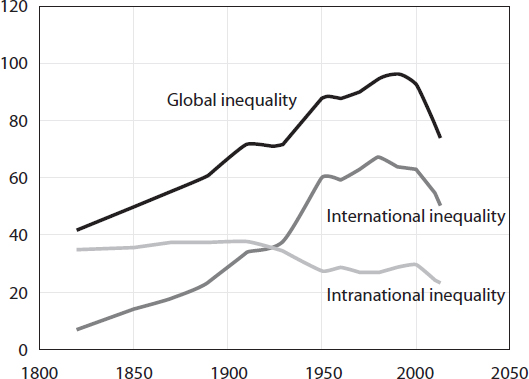

Figure 3.1 shows the evolution of inequality, both in total, and across and within countries, from 1820 to 2011. Inequality across countries increased from about 7% in 1820 to about 70% in 1980. This cross-country inequality has retreated to about 50% since that year, thanks to the rapid development of China and India. On the other hand, average inequality within countries has changed gradually over this period. It increased from about 35% in 1820 to about 38% at its peak just before World War I and then declined to a low of 27% in the 1970s. Since then it has fallen a bit more, to 24%. The average of within-country inequality declined because the increase in inequality within wealthy countries, which we highlighted in the introduction, was offset by the reduction of inequality within many poor countries.

FIGURE 3.1: Global inequality, both in total (black) and decomposed into between (dark gray) and within (light gray) country components from 1820 to 2011.

Source: This series is based on a merger of the data of François Bourguignon and Christian Morrisson, Inequality Among World Citizens: 1820–1992, 92 American Economic Review 4 (2002), and Branko Milanovic, Global Inequality of Opportunity: How Much of Our Income Is Determined by Where We Live?, 97 Review of Econonomics & Statistics 2 (2015), performed by Branko Milanovic as a favor to us.

Together these patterns imply that inequality across countries has gone from a relatively insignificant phenomenon in the grand scheme of global inequality, accounting for only a little more than 10% of global inequality in the 1820s, to being the dominant source of global inequality, accounting for two-thirds or more in the second half of the twentieth century and still today accounting for 60–70% depending on whose measurements you rely upon.9

This puts into quantitative perspective the very different world we confront today, compared to the one nineteenth-century political economists faced. Theirs was a world where a farmer or factory worker in one country enjoyed a standard of living similar to that of a farmer or factory worker in any other country, and all were much worse off than aristocrats. Ours is a world where a child born to an average family in India or Brazil faces a much more impoverished life than a child born to a family in the United States or Germany. Moreover, in modern developed economies, a family of average income enjoys a standard of living similar to that of the very wealthiest families in poor countries. Theirs was a world in which migration did most people little good; ours is one in which migration can be a primary route to well-being and prosperity for most people in the world.

This is not to say that migration, even on large scales, was unknown in the earlier period. Merchants and aristocrats traveled, but rarely to migrate permanently to another country. They did, however, meet with foreigners, learn foreign languages, and intermarry with foreigners. A cosmopolitan outlook emerged that distinguishes the upper from the lower classes to this very day. Leading families also married across national boundaries in order to create alliances, to the extent that kings and queens of countries often were not even nationals, and sometimes did not even speak the national language very well.

On the lower end of the scale of fortune, slaves were abducted from Africa and transported to countries in the Middle East and the American colonies. Poorer Europeans, oppressed by governments or by a lack of property, would migrate to rough-hewn colonies for the opportunity to eventually enter the propertied class. In exchange, they would often sell themselves into indenture arrangements where they would owe service to a master for several years in exchange for the cost of the passage. The hard life of labor available on colonial plantations was hardly much of a lure, one reason that planters resorted to the slave trade.

In such a world, it was natural for the Radicals to focus on the freeing of markets for goods and capital from aristocratic privilege, such as the ending of the British Corn Laws, or ending unfree migration in the form of the slave trade rather than emphasizing free migration.

First, putting aside the important but limited exception of migration to colonial possessions (starting with the New World centuries earlier), free migration would not have significantly increased the well-being of ordinary people. No one benefited from moving from one country to another if he or she was a proletarian or landless peasant in both. Second, migration was relatively unrestricted across countries, and controls upon it were scarcely enforced since there was little demand to migrate and because the primitive, risky, and uncomfortable nature of transportation at the time deterred all but the most desperate or ambitious.10 Third, free trade across countries could break the monopolistic control of landlords over crucial national resources, greatly enhancing national wealth and shifting its distribution from the feudal aristocracy to capitalists and laborers.

Major intellectual debate about migration began only in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the United States, debate was stimulated by the enormous waves of immigration provoked by strife and famine in Europe, and the lure of newly discovered gold, as well as rapid economic development, which attracted millions from Asia as well as Europe. By this time, attitudes among economists toward migration had become more complicated, partly in response to public sentiment.

Karl Marx, for example, worried that strategic use of Irish migration by British capitalists divided the international working class and undermined socialism.11 Radicals and progressives in many countries, including John Stuart Mill and Henry George, who sometimes dabbled with ugly racist and eugenic arguments, shared these sentiments.12 In the early twentieth century, a decisive shift in attitudes toward migration took place. With the growing affordability of travel across continents and oceans, and the increasing differentials of wages across countries, the economic advantages of migration greatly improved, not least for displaced populations following World War I. The United States slammed its doors in the late teens and 1920s. In Europe, with the rise of ethno-nationalistic sentiments, countries tried to keep out those who were thought to pollute their cultural heritage or racial gene pool.

Globalization

These ethno-nationalist sentiments peaked at the outbreak of World War II, which in turn transformed the global order. After the war, Western leaders tried to build an international system that would generate prosperity and prevent economic chaos and nationalist conflict from igniting another war. Among wealthy countries, there was a renewed commitment to open trade and international and regional governance institutions. Starting in the 1980s and 1990s, these international commitments spread, encompassing China and other parts of Asia, Latin America, and Africa. But, while significant intellectual and political resources were used for the building of trade and investment institutions, migration received little consideration.

The postwar economic system stood on three pillars: international trade, monetary and macroeconomic stabilization, and development finance. Each pillar was represented by an institution: the General Agreements on Tariffs and Trade or GATT, the International Monetary Fund or IMF, and the World Bank. The GATT tried to establish an equitable baseline for trade among all participants that would supplement the web of bilateral trade agreements and unilateral tariff policies of the antebellum period. It was gradually strengthened in successive rounds of negotiation, culminating in the Uruguay Round, which created the World Trade Organization, or WTO, in the early 1990s.

This patchwork of international cooperation was mirrored at the regional level, and in the case of Europe these regional institutions became especially strong. Trade agreements spread throughout the continent and gradually strengthened into a web of economic regulation that culminated in the creation of the European Union (EU), followed by the establishment of the Eurozone monetary union involving most of the EU member states. While it never cohered into a federal government structure, European integration moved substantially beyond the purely commercial institutions of the global order to establish substantive governance in many areas of European economic and social policy.

Throughout this period, gaping and growing inequalities between rich and poor countries, together with dramatic advances in transportation and information technology, stirred citizens of poor countries to migrate to wealthier ones. These aspirations were particularly palpable where poor and rich countries met in close quarters: the Rio Grande, which separates the United States and Mexico; between Western and Eastern Europe; and across the two sides of the Mediterranean. In Europe, governments encouraged migration for postwar reconstruction; in the United States, the government permitted Mexicans to cross the border to engage in seasonal agricultural labor. But political opposition to these policies ensured that they were temporary and often involved work-arounds and winking at illegal immigration. In Germany, for example, the government allowed Turkish workers to settle in the country but did not grant them citizenship; in the United States, legal immigration programs were replaced by illegal immigration since the border was not controlled. But whether legal or illegal, migration never reached the level that would satisfy demand in the host countries and the supply of people willing and able to migrate.13

In Europe, migration between EU member states was institutionalized. Citizens were permitted to move to any member state for a job. But the law did not produce as much migration as was hoped. Linguistic and cultural barriers kept most people at home, and income differences between European countries were modest by global standards, reducing the incentive for migration. Where migration did take place, it typically involved movement from lower-wage Eastern European countries like Poland to higher-wage Western countries, including France and the UK, which generated a political backlash in the host states. Additional tensions were created in 2015 and 2016 when Europe grudgingly accepted a massive influx of refugees from war-torn Syria and other countries in the Middle East and southwest Asia. Guest worker systems in other parts of the world, including the states of the Persian Gulf, have been much more successful, as we discuss below, but overall the amount of migration throughout the world has remained limited relative to the potential gains.

Together these institutional developments have created an imbalanced global order. Capital, goods, and highly educated labor flows rapidly across borders, generating significant wealth, while less educated workers tend to stay at home. These weaknesses in globalization have long been recognized by “antiglobalization” activists, though not always expressed in precise economic terms.14 As leftist Latin American journalist Eduardo Galeano put it, “We must not confuse globalization with ‘internationalism’ … One thing is the free movement of peoples, the other of money. This can be seen … (at) the border between Mexico and the United States which hardly exists as far as the flow of money and goods is concerned. Yet it stands as a kind of Berlin Wall … when it comes to stopping people from getting across.”15 Those promoting globalization, with their focus on capital rather than on ordinary people, failed to ensure that welfare gains would be widely shared.

The Migration Imperative

There is a consensus that the economic gain from further opening international trade in goods is minimal. Studies by the World Bank and prominent trade economists find that eliminating all remaining barriers to international trade in goods would increase global output by only a small amount, 0.3–4.1%. For global investment, the most optimistic estimate in the literature finds a 1.7% increase in global income from the elimination of barriers to capital mobility.16 Many believe that liberalization of international capital markets has gone too far. Three top IMF economists recently argued that even liberalization that has already taken place has brought limited gains to economies while generating inequality and instability.17

At the same time, the benefits of liberalizing migration have dramatically expanded. Sharp reductions in transportation costs have made the natural barriers to migration de minimus compared to the potential gains. On the other hand, the potential economic benefits of migration have exploded. A typical Mexican migrant moving to the United States increases her annual earnings from roughly $4,000 to roughly $14,000, and Mexico is a quite wealthy country by global standards. Potential gains from migration from poor countries to Europe and the United States, especially if language barriers are low (as in the case of Haiti and France, for example), would involve gains of as much as ten times, involving tens of thousands of dollars per migrant.

To take an extreme but illuminating example, imagine that the countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the club of wealthy countries, were to accept enough migrants to double their population, presently at 1.3 billion. This would move roughly 20% of the global population to the OECD. Suppose too that each migrant on average created income gains of $11,000. This would constitute an increase on average of roughly $2,200 for every person on the planet. Given that global income per capita is approximately $11,000, this is roughly a 20% increase in global income. If historical experience is any guide, gains to those who stay in poor countries would be equally dramatic, as most migrants remit a large fraction of their income to the countries they came from.18 In sharp contrast to trade, these gains have transformative potential for global well-being, if they can be harnessed and shared.19

Why Not Just Expand Existing Migration?

Some scholars who are aware of these numbers have declared that opening borders is the only morally acceptable response. If countries allowed unlimited immigration, then the poor workers in capital-starved countries would migrate to wealthy countries like the United States, where their wages would be much higher. While the huge surge of migration would reduce the wages of workers in wealthy countries, global well-being would increase enormously.

The idea is not as farfetched as it might seem. The borders of the United States were open for more than half of its history, and the effects were as theory predicts. Migrants benefited from higher wages and Americans benefited from the migrants, who helped build railroads and canals, who worked in mines and on farms and in factories. The social problems brought on by migration were often severe—including a considerable amount of civil strife—but manageable, and over the long term the country prospered. But today, open borders are impractical both economically and politically.

In their famous 1941 treatise, “Protection and Real Wages,” Wolfgang Stolper and Paul Samuelson (who we met in the previous chapter) investigated the effect of international trade in goods or labor on the incomes of various people within different countries.20 While trade between a pair of countries always increases the aggregate wealth of both countries, it can have important redistributive effects. Trade tends to benefit the factors of production that a nation has in relative abundance and to hurt those it has in relatively scarce supply. Wealthy countries, by definition, have a greater relative abundance of capital as compared to labor than do poor countries. It is thus natural that trade and migration should both benefit capitalists in wealthy countries and laborers in poor countries at the expense of laborers in wealthy countries and capitalists in poor countries.

While the logic of the Stolper-Samuelson Theorem is widely accepted among economists, the exact extent to which various categories of workers are harmed or benefited by immigration is more complex. There is significant evidence that immigration reduces the wages of native workers whose backgrounds are similar to those of migrants. For example, illegal immigration to the United States from Mexico and Central America tends to hurt native workers with low education and weak language skills.21 However, the effects of migration on the broader labor markets are murkier. Some scholars believe that the native workers are in aggregate harmed, albeit only to a limited extent.22 Others argue that effects are negligible or even that most workers may benefit because migrants buy more goods, which native workers produce, or take the lowest rungs on the employment ladder, pushing some native workers up into better-paying supervisory roles.23

These small and mixed effects are dwarfed by the large benefits migration brings to the migrants themselves and their employers.24 Moreover, the fiscal structure of migration prevents significant sharing of these benefits through government and may even impose costs on domestic workers. The nature of and reasons for this arrangement differ between the United States and Europe.

In the United States, the tax system is limited in its progressivity and effectively excludes a huge number of immigrants, those who are undocumented. While high-skilled, welleducated legal migrants are net contributors to the tax system in the United States, because of the low tax rates on labor and capital income in the United States, such migrants do not make significant contributions that directly benefit native workers through the fiscal system. Many start businesses that generate employment opportunities,25 but these opportunities are in high-growth, entrepreneurial sectors of the economy that are geographically concentrated in prosperous metropolitan regions, away from where most workers live in the United States. Together these considerations mean that few native workers see large, direct benefits from high-skilled migration.

Most low-skilled migrants work outside formal channels of employment. They tend to pay few taxes. Furthermore, because most of these migrants come from poor countries and have indigent families in their homelands, they send much of their earnings back to the poor countries from which they come, recycling less of their earnings into local economies than native workers at similar income levels. Thus, migrants make at most a very modest contribution to public coffers relative to the benefits they and their employers gain from their migration, and some studies even suggest migrants may be a modest net fiscal drain on the state.26 Patterns in the UK resemble those in the United States, with low-skilled migrants from Eastern Europe taking the place of those from south of the border in the United States, though in smaller numbers and with a smaller gain.27

In contrast to the United States, European countries other than the UK have highly progressive systems of capital and labor taxation that allow the broad public to benefit from the successes of migrants. However, because of these tax systems, because the Continent no longer hosts the world’s greatest universities, and because the Continent has been less successful in fostering entrepreneurship than the United States, fewer high-skilled migrants relocate to Europe than to the United States.

On the low end of the skill distribution, illegal migration to Europe in large numbers is a relatively recent phenomenon dating back only a few years to the migrant crisis triggered by the Syrian Civil War. Much of legal low-skilled migration comes from Eastern Europe. Most low-skilled non-Europeans in Europe either hail from distant former colonies or are refugees taken in for primarily humanitarian rather than economic reasons. These migrants tend to be significantly poorer than those coming to the United States. Furthermore, continental European countries have a more generous set of social benefits, transfers, and public services than the United States. Because migrants are generally entitled to equal access to these benefits, low-skilled migrants are a significant drain on public finances in Europe in a way that they are not in the United States.

Underfunding of public services in Europe has contributed to these tensions. Many Europeans are not just abstractly aware of the possibility that migrants strain social services, but also see with their own eyes migrants competing for access to these services. Because of the historical homogeneity of many continental European countries, this competition is visually striking because migrants are easily recognizable by skin color or religious practice. In short, both the impression and to some extent the reality European workers’ experience is of migrants acting as an added burden on public services and a weak economy.

While one might assume that natives living in areas with the highest migrant populations object to migration more than other people do, social science evidence is mixed. Often it is in the rural and economically depressed regions where few migrants reside that opposition to migration is strongest.28 Workers in such areas see migration adding to economic vibrancy in other communities, but not in their own. They gain none of the ancillary social and cultural benefits that dynamic city-dwellers gain from migration, of increased variety in food, color in urban life, or exposure to other cultures that can expand career opportunities. Instead, they see the rest of their country moving in directions that distance it from their experience in ways that increase their isolation and consignment to the cultural periphery.

Let us sum up. While migration offers enormous advantages to the migrants themselves and their families back home, to employers and owners of capital, and to the high-skilled workers who they complement and live among, migration offers few benefits to and imposes some costs on most workers in wealthy countries, who are already left behind by the forces of trade, automation, and the rising power of concentrated finance. Coupled with natural human instincts toward tribalism, which have been stirred up by nativist politicians, broad and growing political opposition to migration has set in. Majorities are unlikely to support migration policies that do not benefit most citizens. In the United States, the elites who controlled government and supported migration managed to evade political opposition by refraining from enforcement of immigration laws, but in doing so they set the stage for a populist backlash.29 In this sense, slogans such as “America First” and “on est chez nous” (this is our home), while offensive to many, capture an inescapable aspect of political reality.

Auctioning Visas?

Most migration to OECD countries is controlled by government bureaucrats or private employers, who can apply for visas for high-skilled workers whom they want to hire. Another portion of the immigration system allows for immigration of close family members of citizens (especially in the United States) and for people of the national ethnic stock (especially in European countries). These systems are to a large extent top-down and statist or controlled by concentrated economic interests like employers. It is thus hardly surprising that they benefit employers and migrants the most. In short, the system of migration suffers from the same problems as our economy and democracy: a combination of inequity and often arbitrary government discretion.

In the previous two chapters, we have seen that auctions offer a simple framework for replacing such systems, though they often need to be adapted to practical considerations. The same is true of immigration. In an insightful 2010 lecture, the late Nobel Laureate Gary Becker proposed a simple auction-based system for migration: set a quota for migration and auction off the rights to enter the country to the highest bidder.30 The revenue raised by this Radical Market could be used to fund public goods or a universal social dividend, as we saw with common ownership of property in chapter 1.

As with the simplest auction-based ideas of the previous chapters, this scheme has a number of limitations that we will address. However, notice that it immediately addresses a number of weaknesses in the present migration system.

First, it ensures that a large share of the gains from migration accrue to ordinary people rather than businesses. Hence, it would advance equality. Second, and as a consequence, it would soften political opposition to migration. Third, the program would greatly reduce the role of government bureaucrats and instead harness the knowledge of the migrants who best understand the economic prospects open to them. A stream of recent economic research has shown that migration systems that rely most heavily on bureaucratic judgments of migrants’ merits (so-called points-based systems, where migrants with educational credentials and the like receive priority) tend to fail.31 Systems that put employers in charge seem to work better than points-based systems but, as we have noted, allocate gains mostly to employers. An auction-based system avoids both of these pitfalls.

An auction-based system could raise a remarkable amount of revenue to improve the living standards of ordinary citizens in wealthy countries while still delivering enormous benefits to migrants. Suppose that OECD countries accepted enough migration to increase their populations by a third. Suppose too that migrants on average bid $6,000 per year for a visa. This sum seems plausible given that even illegal Mexican migrants to the United States gain more than $11,000 annually under the current highly inefficient system. Average GDP per capita in OECD countries is $35,000, so this proposal would boost the national income of a typical OECD country by almost 6%, comparable to their growth in real income per person in the last five years.

Imagine that the gains from this growth are equally distributed among all citizens. This would effectively reduce the share of the top 1% of income earners by 6% as only a small part of this gain would accrue to the top 1%. This equals a reduction by about 1 percentage point, going an eighth of the way toward restoring the trough of inequality midcentury in the United States. Median household income for a family of four in the United States is about $50,000. Such a family would earn roughly $8,000 under such a system and thus would see their income rise by about 15%, roughly equal to all inflation-adjusted gains for such families since the 1970s.

Gains to migrants would be even more dramatic. Depending on who migrated, an increase of $5,000 (the $11,000 gain minus the $6,000 bid) of income could increase migrant income by many times, given that most migrants would come from countries with typical annual incomes of a few thousand dollars or less. Under this scenario, about half the dollar gains would accrue to OECD countries and about half to migrants and those they remit funds to. Because the OECD represents half of global income, the global economy would grow roughly 6–7% as well.

Nonetheless, the auction system in its purest form has several weaknesses. Clearly, money is not the only thing that matters in migration. Cultural fit to local communities, likelihood of committing crimes or disobeying the terms of a visa, and the willingness of employers and host country citizens to welcome a migrant are all crucial components of the social value of the migrant. A pure auction ignores these factors. Nor is money the only factor that is important to sustaining political support for migration. Positive cultural, social, and economic interactions at a personal level between migrants and natives is critical. A simple auction would do little to ensure this occurred. But, drawing inspiration from the auction and important features of existing migration law, we can formulate a solution.

Democratizing Visas

In the United States, under the H1-B program employers “sponsor” migrant workers. Google can hire a software engineer from another country (say, India) by obtaining a visa for the worker, which allows the worker to reside in the United States for three years, renewable for a second three-year period, subject to various restrictions (including the limited number of available visas). Family members can also sponsor visas under the Family Reunification policy. Our proposal, which we call the Visas Between Individuals Program (VIP), would extend this system so that any ordinary person could sponsor a migrant worker, albeit with some adjustments to reflect the difference in circumstances, and for an indefinite period rather than a renewable three-year period. We would allow people to sponsor one migrant worker at any moment in time. This could either bring a rotating cast of temporary guest workers (one at any time) as in our opening vignette or one permanent migrant over a lifetime.

The major difference, of course, is that sponsors are no longer necessarily employers or family. When Google sponsors a migrant worker, it gives her an office and (probably) helps her find a home and settle in the community. The worker contributes to Google’s bottom line by writing code, and Google compensates the worker out of that surplus. Google also employs an experienced bureaucracy to fill out a lot of the paperwork and deal with immigration authorities, and also search for and evaluate foreign workers who possess the desired skills. The worker flourishes in Google’s multicultural workforce where people are evaluated according to their merit, not their race, ethnicity, or national origin.

By contrast, Anthony is a recently laid-off construction worker who lives in Akron, Ohio. He has a high school education, a small amount of savings, and limited prospects. He has not met many foreigners, and feels a bit of resentment toward a group of Middle Easterners who recently moved into his neighborhood and opened restaurants that serve food that Anthony does not like much. (He does acknowledge, however, that they have brought new life to his neighborhood and many of them have taken jobs that he wouldn’t touch.) Anthony learns of a new program offered by the State Department that allows him to sponsor a migrant worker and earn money in the process. Anthony is interested, but what’s in it for him? Unlike Google, he can’t simply place the worker in an office and expect the worker to generate revenue for him.

Using a website operated by a company that contracts with the State Department, Anthony describes the sort of worker he is willing to sponsor. English is a necessity. Anthony asks for someone in his twenties, who has worked in the construction industry, and has no criminal record or health problems. Anthony knows from job contacts that several new construction projects are being planned on the outskirts of Akron, and hopes to place a foreign worker at one of them. And if this falls through, Anthony also wants to start a handyman business and can use the worker as an employee. The website puts Anthony into contact with a Nepalese man named Bishal. Bishal has worked as a guest worker in the United Arab Emirates, where he improved his patchy English. Anthony interviews Bishal over the web, where he spells out his plan, and the two agree that Bishal will work for Anthony for one year in the United States for $12,000 (likely to be as much as five times what Bishal can earn in Nepal if he is lucky enough to get a job). Anthony will need to use his savings to buy Bishal a plane ticket. They agree that Bishal will reside in Anthony’s spare room.

We can, of course, tell an optimistic story about what would happen next, and our opening vignette offers one such story, but we are under no illusions that every story must end happily. In the happy story, Bishal arrives in the United States with the clothes on his back but little else. But Bishal, who has experienced hardships that few Americans can even imagine, flourishes. For the first month, he works as a handyman in the neighborhood. Anthony charges customers just $10 per hour for Bishal, and so after paying Bishal $1,000 for the month, Anthony barely breaks even. But then Bishal obtains the construction job. The construction company realizes that Bishal has some significant skills that he obtained in the construction industry in the UAE, and ultimately pays him $20,000 for the remaining eleven months. Anthony collects the $8,000 balance. Meanwhile, Anthony and Bishal get to know each other. Perhaps they become friends. Bishal helps around the house, and Anthony acquires a taste for Nepalese food.

Of course, it need not turn out this way. What if Bishal cannot find work? Or he becomes ill and needs to be hospitalized? Or what if he commits crimes, or simply disappears? (He travels to another part of the country and works illegally.) It is necessary to make Anthony responsible in such a case so that sponsors have good incentives to screen out migrants who will not contribute. Rules of this sort exist elsewhere in our current immigration system. For example, sponsors under family reunification programs must provide financial support for migrants who cannot support themselves.

In our case, Anthony will be required to obtain basic health insurance for Bishal before he arrives (though this would come out of Bishal’s earnings). If Bishal is unable to find work, Anthony must support him for as long as he remains in the country. Bishal is not entitled to welfare payments. If Bishal commits a crime, he will be deported after serving his sentence; Anthony will be required to pay a fine. If Bishal disappears, Anthony will also be fined. We do not think that the fine needs to be large, but it should sting. Also, Anthony and Bishal might not be able to stand each other. Perhaps Anthony can find Bishal a place to stay and pay the rent. Or they can mutually agree that Bishal will return to Nepal after being paid for his time in the United States. It may also be possible, through mutual agreement, for Anthony to place Bishal with another sponsor (such as a Nepalese family that lives down the street).

For this system to work, the law must make two further adjustments. First, migrant workers must be permitted to work for below the minimum wage. Under current law, a worker paid the federal minimum wage would receive almost $15,000 in one year. By way of comparison, the average annual income in Nepal is less than $1,000 and typical Nepalese make closer to $500; Haiti has similar living standards. Application of the federal minimum wage to migrant workers would block the enormous welfare gains that the VIP would otherwise produce. However, all other worker protection rules—for example, those relating to workplace safety—would apply to them.

Second, immigration enforcement would need to be strengthened. If Bishal disappears into the underground economy, there must be a reasonable likelihood that he will be caught and deported. Existing illegal migrants would have to be fit into the system through a combination of a one-time amnesty with a path to citizenship, finding sponsors, or being deported. Enforcement against future illegal migrants would have to be more stringent to avoid undermining the rights of both the large new class of legal migrants and their hosts. No legal reform can be effective unless it is enforced. However, enforcement of the VIP system would be easier than the current system because migrants desperate to enter the country can more easily find sponsors and thus avoid the risks of illegal entry.

Many people may object to this system. Perhaps to some readers it is uncomfortably similar to indentured servitude, even though migrants would be free to leave at any time. Or perhaps it just seems exploitative. But our proposal is continuous with existing programs that are broadly accepted.

Consider the H1-B visa program, which provides the major avenue for migration by skilled workers to the United States. Under this program, an employer sponsors a worker by certifying that the worker satisfies various criteria and that he will be paid the prevailing wage. After the worker arrives, he must work for that employer. If the employer fires the worker, then (subject to a few exceptions) the worker must return to his home country. The major difference between the H1-B program and the program that we propose is that we would allow ordinary people to be sponsors. The H1-B program is not controversial. The risk of exploitation is minimal because foreign workers are protected by the same health, safety, labor, and employment laws that Americans benefit from, and foreign workers can return to their home country if the employer mistreats them.

One might believe that employers—or, at least, large corporate employers like Google—will treat foreign workers in a more benevolent way than ordinary people would, or at least in a bureaucratic rather than exploitative way. Can ordinary people be expected to “manage” a foreign employee? Indeed, they can. There is another program that is even closer to the one we propose. Under the J-1 visa program, Americans can sponsor people, typically young women, who work as au pairs for a year or two and live in their homes. While the J-1 visa program was initially designed for cultural exchange, Congress has permitted people to use it for what is essentially low-wage nanny work. The program is very popular. Note that ordinary Americans serve as employers and sponsors, relying on intermediary institutions—private companies—which help match American sponsors to the foreign workers, provide training to the au pairs, and monitor working and home conditions after they arrive, all subject to regulations and supervision by the State Department.

The au pair program, while nominally a cultural exchange program, is virtually the same thing as the guest work program that we propose, except that it is limited and more highly regulated than we believe necessary. While some people argue that the au pairs are exploited, we have not found any studies that document abuses.32

The au pair program also provides clues as to how our program might work in practice. The intermediary institutions have developed easy-to-use websites that allow families and au pairs to match up with each other. The host family is allowed to register its preferences about such things as whether the au pair is licensed to drive, how well she (usually) speaks English, what part of the world she hails from, her experience, her interests, and so on. The au pair applicant also registers her preferences. The institution then sends a small number of profiles of matching applicants to the families. The profile includes detailed information about the applicant’s background, interests, skills, and so on. The host family can interview some or all of the applicants, or reject them, whereupon the agency will send the family another group of profiles. The interview takes place over Skype.

Once an applicant is selected, she goes through a week of training—in which she learns about American ways of doing things—and then is sent to the host family. The agency periodically sends people to check on the au pair and family. Among other things, it interviews the parties privately. If one or both sides are unhappy, then the agency will try to match the au pair with another family, so that she will not have to return to her home country.

While the VIP would grant the primary right to sponsor migrants to individuals, communities could also be granted the right to regulate migrant entry. Localities should be allowed to put limited constraints on their residents’ use of the VIP program, akin to zoning regulations. We might predict that some communities will prefer a higher level of openness and impose no or few restrictions, while offering amenities that attract foreign migrant workers. These communities might hope for a vibrant, culturally mixed public life. Other communities will prefer homogeneity and use tax and zoning restrictions to limit the influx of migrants. Natives might move across communities, to the opportunity offered by more open cities. In this spirit, it might be natural to pilot VIP in a community that would act as a “special economic zone,” using the program as a way to revive a currently depressed area and to investigate its potential advantages and drawbacks without disrupting a whole community.

While the VIP would achieve nearly all the benefits of Becker’s visa auction, it would also address its primary weaknesses. Becker’s auction is run by the government, not by individuals or communities. It will attract migrants who are willing to pay the most regardless of whether certain types of migrants may cause social or cultural harms to the communities in which they settle. The VIP places the discretion with natives, subject to community regulation. Individuals and communities care about money and thus VIP would likely lead to prevailing prices migrants would have to pay to hosts to be fairly similar to those prevailing in the auction. But as anyone who has worked or has offered a job to someone knows, money is rarely the sole factor in determining the success of such relationships. By placing individuals and communities in charge, VIP allows these individuals and communities to include other factors in decisions about which migrants to allow.

Also unlike Becker’s auction, the VIP would involve personal contact between natives and migrants, and responsibility on the part of natives for the success of a migrant. Such mutually beneficial contact is likely on average, though surely not in every single case, to build the sort of positive relationship between hosts and migrants necessary to soften political opposition to migration. By empowering communities to decide the texture of their cultural life, the VIP would avoid the negative reactions that are possible when people feel rapid changes are being imposed from above.

INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORTS

With the powerful advantages that it has over the existing system of migration and over the auction, the VIP system comes with some drawbacks. Anthony may be too busy and lack the personal or managerial skills or the knowledge of the local economy needed to navigate the VIP system. Call this the “competence problem.”

Anthony might also mistreat or exploit Bishal. While Bishal has the formal right to leave at any time, he may be unwilling to exercise that right, even in extreme circumstances. Imagine that his family depends on his remittances, or that he left Nepal in the first place to escape crime and corruption. He will put up with a great deal in the United States before returning to Nepal, and this means he is vulnerable to abuse. Knowing this, Anthony might illegally withhold wages from Bishal, deprive him of adequate food and housing, and even compel him to engage in criminal activity. Call this the “exploitation problem.”

Issues such as the competence problem show up in virtually every aspect of market economies. People must manage their pensions, mortgages, credit cards, job searches, and other complex economic relationships. Dozens of institutions have emerged to help individuals navigate these obstacles. Some individuals educate themselves to become experts; others draw on markets for personal services or assistants; others use online platforms that spring up to help with screening. In the worst case, some people will abstain from participating as sponsors. But we suspect most will use institutions to help them navigate the VIP system.

Exploitation is a more serious problem. Labor and human trafficking laws exist to prevent employers from trapping workers in coercive relationships. Excepting the minimum wages we discussed above, the full force of such laws should be applied to the VIP.

It is important to recognize the powerful ways in which the structure of the VIP would reduce the risk of exploitation relative to the current system of migration. Workers are most vulnerable to exploitation when their employment options are limited or they operate as illegal immigrants, outside the protection of the law. When potential employers are forced to compete, workers tend to prosper. This competition is precisely what the VIP promotes: at present, only a few powerful corporations can sponsor visas. Under VIP, every citizen will be able to. The more countries that adopt a VIP system and the more citizens that decide to host, the more options will be available to migrants.

Could VIP Work?

The restructuring of migration we propose is radical—another Radical Market, this time in labor. Could it ever attract the necessary popular support or be sustained? Some recent experience is encouraging.

The migration systems in the UAE, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Oman, and Saudi Arabia (countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council, or GCC) are often criticized, but they tell an interesting tale. Where the United States has roughly nine natives for every foreign-born resident, the ratio in the UAE is reversed.33 Bahrain and Oman host roughly one migrant for every native. In Saudi Arabia, the GCC country with the fewest migrants per native, there is one migrant for every two citizens.

Nor are the GCC countries the only successful countries with such large noncitizen populations. Singapore hosts two migrants for every three natives. Australia and New Zealand have roughly one foreign-born resident for every two natives. Some prosperous and successful cities, such as Toronto, have levels of foreign-born residents (50%) similar to the GCC.

Yet despite these large migrant populations—in all cases, involving mostly low-skilled migrant workers—none of these countries (with the possible exception of Australia) has experienced as large a popular backlash against migration as OECD countries with far fewer migrants.

All of these countries have migration systems designed for the benefits of migration to be broadly shared among natives rather than exclusively accruing to a small group of geographically concentrated capitalists, entrepreneurs, and high-skilled workers. Despite this sharing, the total benefits per native created by migration in these countries to migrants and the countries that send them is far greater than in the more closed OECD countries, because the volume of migration is so much greater. Beyond these features, the migration systems of these countries differ widely.

In the GCC, migrant workers enjoy few civil rights, are tightly controlled by the government and, except for the large domestic servant population, live in segregation from natives. However, in these countries most natives have benefited from publicly owned wealth distributed in a reasonably egalitarian manner, and the state has firm control over the social organization of migrants to prevent crime and uprisings. Furthermore, as in VIP, natives can sponsor migrants for tasks that benefit them. Thus, political support for this massive scale of migration has been strong and sustained for years.

Of course, an important cost of these systems is their neglect of the rights of their migrant labor force. After all, the GCC countries are monarchies and many conform to traditional Islamic law in harsh ways. In some cases, some GCCs have allowed natives to exploit migrants who are unable to leave because their passports have been confiscated by their employers. For all these reasons, the GCC countries are not a model for OECD countries. Yet Singapore has sustained near-GCC level migration with many fewer concerns about violations of migrants’ rights.

While we do not want to imitate the systems in these countries, we describe them because they hold an important lesson. A political backlash against massive migration is not inevitable. Even in closed societies, migration receives political support as long as its benefits are widely distributed in a visible way.

An Internationalism of People

There are about 250 million adults in the United States. In principle, they could sponsor 250 million migrants every year under the VIP program. In practice, we suspect that many people—especially the elderly, those busy with their jobs, and students—will forgo the opportunity. Imagine, then, that 100 million people sponsor migrant workers. Currently, there are about 45 million foreign-born people in the United States. Of those, about 13 million are legal noncitizens, and 11 million are illegal aliens. If our program replaced existing migrant worker visas, the number of migrant workers would increase dramatically, from 24 million to 100 million, but not in a way that would disrupt society and overwhelm public services. It would leave the ratio of foreign-born to natives in the United States below the numbers in even the most restrictive GCC countries.

We expect that the people who use the program would be a cross-section of society. We already know that upper-middle-class people use the J-1 program to sponsor au pairs. Our aim is to involve working-class people who would be attracted by the financial benefits of sponsorship. A low-income person who can earn $6,000 on net from sponsoring a low-skilled migrant worker will significantly increase her well-being; in contrast, a middle-class or wealthy person is not likely to find such an opportunity attractive.

This is the key reason for the program. If ordinary people like Anthony both gain financially from migration and learn something about the humanity and needs of foreigners, their opposition to immigration will decline. Eventually the number of migrants could be expanded if no serious social problems were encountered and the program was popular.

To be sure, the increase in the number of migrants will likely suppress wages for some jobs. In this sense, our proposal is no different from proposals to open borders or increase the number of visas. The key difference is that in our proposal, many of the people who might be hurt by wage suppression will also gain by participating as sponsors in the program. The benefits of migration will be distributed more fairly, reducing political opposition to it.

Furthermore, the large increases in migration would likely make activities that are currently uneconomic in OECD countries viable again, as the example of the GCC countries and our opening vignette illustrate. Factories that have moved abroad could return, offering new jobs for natives, if abundant migrant labor were available, as a political party in Australia led by Nick Xenophon has argued in recent years. Many of the fears of the effects of migrants on wages are actually more justified at our current, low levels of migration. In GCC countries, where migration is much higher, migrant wages are so low and migrant labor so plentiful that migrants engage in activities (domestic service, low-skilled manufacturing, etc.) that are clearly uneconomic for employing natives. Such activities are usually large enough in scale that they require native employers and supervisors, offering direct benefits and often even employment to natives, as illustrated in our opening vignette.

In some ways, the effects of large-scale migration as we envision it would be similar to those of women’s entry into the labor force over the mid-twentieth century, as economist Michael Clemens argues in a forthcoming book, The Walls of Nations.34 Yes, women competed with men in the workplace, causing some dislocation and resentment. But because most men had close relationships with women, as fathers, husbands, brothers, and sons, they benefited from greater opportunities for women more than they were harmed at work and thus were reconciled to the additional competition. At the same time, while sexism persisted, a growing professional presence for women began to break down stereotypes and patriarchy.

Similarly, our proposal to tie the economic fate of hosts and migrants would gradually reduce conflict between the workers of the developing and developed worlds and benefit both. VIP would be less disruptive to the identity of host country workers than women’s entry into the workforce because it would not directly affect existing hierarchies in the highly intimate sphere of the home.

The greater fairness of VIP can be seen by comparing it to the present arrangement. Under the H1-B program, as a practical matter, only large and sophisticated employers—the Googles—can sponsor migrant workers. Why should they alone enjoy this benefit? Why shouldn’t ordinary people? It’s as if wealthy women were allowed by the government to enter the workplace, while poor women were prevented from doing so “for their own good.”

One might worry that Google will try to take advantage of our program by encouraging its employees and others to sponsor programmers and contract them to Google. But now, serving as middlemen, sponsors would obtain a cut of the profits. If Anthony hears that Google’s Akron office needs programmers, he can look for programmers. Anthony will still gain from the sponsorship, as will the migrant worker and the local economy.

Who would come? Most likely a mix of unskilled workers like Bishal and skilled ones as in our Google example. The illegal economy is currently dominated by low-skilled workers—strawberry pickers, nannies, gardeners, slaughterhouse workers. VIP would put this work on a legal footing, while channeling some of the surplus away from the employers and into the pockets of native workers. Skilled migrants would be treated like any other migrants under our system. They would earn far greater income than unskilled migrants and thus there would be substantial competition among hosts to gain a share of their income. The program might also be designed to allow a host to sponsor permanent citizenship in exchange for that host relinquishing her right to host again during her lifetime. Skilled migrants would thus also likely be able to negotiate permanent citizenship or sharing a smaller fraction of their income with hosts.

Probably the most important concern is that VIP would increase inequality in host countries. Host country middle and working classes would benefit, while a new class of very poor (by American standards) migrant workers will form a new subordinate class, which might seem intolerable under liberal norms.

However, there are three reasons for resisting this conclusion. First and most important, it is crucial to recognize that such migration would not create inequality (in fact it would reduce it). It would merely make more visible the inequality that is currently obscured by national borders. To the extent this occurs, we believe it would largely be a salutary effect as it would begin to expose and soften a global system that keeps extreme poverty out of sight and mind for the people of wealthy countries.

Second, this process of disruption through greater awareness and proximity of inequality will be greatly mitigated by the likely temporary nature of migration in the VIP. The new class will consist of a constantly changing flow of foreigners who come here voluntarily to obtain wealth and skills, and then return to their home countries where they will be able to make a better life. Evidence from sociological and economic studies of migration indicates that when migrants have the option, most prefer temporary migration for work in circular patterns over permanent migration.35 The experience in the GCC countries is strongly consistent with this pattern, with waves of migrant workers rotating in and out. Only when this option is foreclosed do most attempt to move permanently. This kind of circular migration does not create the pathologies normally associated with class divisions, where the lower class consists of people who are born into an involuntary status they can never leave.

Third, while inequality within the United States might rise (reflecting the lower wealth levels of the foreign workers), both inequality among US natives and global inequality will decline. That is of course the lesson of the GCCs. Bishal will see his annual income increase by five times, or more. He will send home remittances to his family, and when he returns home, may have accumulated enough capital—as well as skills, including improved English language skills—to start a business or get training for a higher-paying job. In the era of open borders in the United States, many migrant workers who came from Europe to the United States returned home to do just this. By reducing global inequality, this process will also gradually reduce the demand for migration and raise the wages of workers all over the world.

Fourth, we need to acknowledge that we in the United States already have a subordinate class of low-wage workers—they are illegal aliens. Americans have exploited this class for decades, and it has for those decades been tolerated by the US government because of its importance for many industries. By bringing this underground economy into the open, our approach would allow it to be regulated and monitored. It would be put on a more rational basis so that better matches are made between the needs of the US economy and the interests of foreign workers. And rather than its benefits flowing to capitalists, it would be shared by all citizens.

The nature and extent of these concerns will depend on the volume of migrants. If most citizens, rather than just a third (as we envisioned), chose to participate, migration could nearly double the population of the host country. However, VIP would be self-regulating. As more migrants arrived, the gains to natives would fall, and fewer natives would choose to sponsor migrants.

The VIP program, if adopted in multiple countries, would create a vast and fluid international market in migrant labor. Immense benefits would flow both to the poorest of the poor in the developing countries, and to the left-behind, alienated, angry working classes of developed countries, who have been the locus of so much political conflict. It is not unreasonable to hope that as foreigners cycle through developed countries, the local populations not only gain monetary benefits but also develop some sympathy and understanding for different cultures. Such a decline in xenophobic sentiment could pay dividends for international cooperation.

This is not to deny that there is something disquieting about the subordinate position in which VIP would naturally place migrant workers. The attitude toward these workers that it would engender, at least in the short term, is unlikely to be enlightened and egalitarian respect. Instead, we would expect some hosts to develop a sense of paternalism and condescension toward the migrants they host, as illustrated in our vignette.

While such an outcome is far from true equality, it is the best that can be hoped for in the near term. Many of the sophisticated cultural elites most likely to object to this sort of unequal relationship should contemplate their own relationships to migrants. In our experience, most people living in wealthy cities who consider themselves sympathetic to the plight of migrants know little or nothing of the language, cultures, aspirations, and values of those they claim to sympathize with. They benefit greatly from the cheap services these migrants offer and rarely concern themselves with the poverty in which they live. The solidarity of such cosmopolitan elites is thus skin deep. But it is better than the open hostility many ordinary citizens of wealthy countries feel toward migrants.

The VIP program would thus move the desperation of the world’s poorest out of the shadows, offer a real path to opportunity, and turn the indifference and hatred of the rich world into benevolent condescension (at worst) and, in many quarters we suspect, real sympathy. This is a moral gain relative to the hypocrisy of our current system and perhaps the only plausible way toward a more just international order.