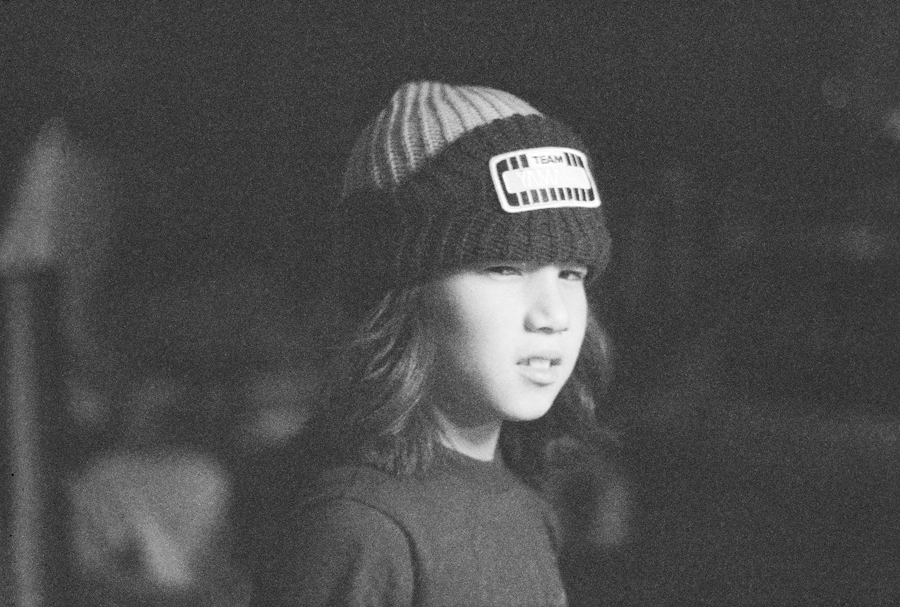

FIRST EVER PUBLISHED PHOTO OF ME, IN SKATEBOARDER MAGAZINE. TAKEN IN 1979. PUBLISHED IN JUNE 1980. © TED TERREBONNE.

“My dad sets the carved wooden box on the kitchen table, opens it, pinches a large amount of weed, breaks it up with his fingers, and sets the leaf fragments on the table. Next he takes a rolling paper from the box and lays it on the table, next to the weed. Scooping the weed into his palm again, he sprinkles it onto the paper strip, saying something about not making the joint pregnant as he evens out a bulge. This makes my best friend Aaron Murray and me laugh. “Be sure to roll everything up tightly,” my dad adds, rolling the joint and licking the edge of the paper before pressing the thin cigarette firmly between his fingers. “That’s how you roll a joint,” he concludes proudly, lighting it, taking a big hit, and passing it to me. I take a hit, cough, and pass the joint on to Aaron, who also takes a hit and coughs. We smoke the joint down to ash, and by then we’re really high and I’m laughing so hard it’s ridiculous. Aaron and I are eight years old, and from then on we roll our own joints and get high all the time.”

Don’t be too rough on my dad. He doesn’t think like anyone you’ve ever met. He reasons differently: he used to say that I was a hyper kid and that pot settled me down. Even now, after all those years, he defends his weed solution for hyperactivity, saying it was better than what they prescribe now, Ritalin. I’m not sure about that one, but believe it or not, he and my mom have taught me some great values, mostly by example. From them I learned loyalty, honesty, not to steal or cheat, and always to try my best. They’ve always told me that I can accomplish nearly anything I put my mind to if I give it my best shot. And I always do give it my best shot, no matter what the odds. I don’t blame anyone but myself when I fall, but I have to thank my parents for the rise.

THE BEST DYSFUNCTIONAL FAMILY EVER

Everyone calls him Pops, and everyone I know knows him. Take a look at those old films of me skating against Tony Hawk and you’ll spot him—that Hawaiian-looking Japanese man at the edge of the pool, probably holding a camera. He was one of the few parents there to watch his kid skate. He was there for me when I was winning, but also later, when I lost everything. I’m an only child, and he gave all of himself to me. He was so cool that every kid I knew wished he was their dad. But there was nothing normal, traditional, or patterned in the way he raised me—or should I say, in the way he let me raise myself. From the beginning our lives were over the top.

When I’m eighteen months old, we all live in an apartment in the Bay Area. My parents leave me alone for a moment and I half-crawl and half-walk out a window and onto the roof of the apartment. When he hears a woman scream that there’s a baby on the ledge, Pops runs out to get me. By the time he arrives I’m looking over the edge. He coaxes me into crawling over to him and then he grabs me by the arm and lifts me to safety. Apparently I smile the entire time as he carries me back into the house. I don’t recommend anyone trying it, but hanging from a steep ledge must be good training for blasting high airs. Maybe that’s why I’m never fearful skateboarding.

I have another advantage as a skater: I’m skating before I can even walk. I’m just a newborn when our family friend Jim Ganzer brings a skateboard by our house in Beachwood Canyon, Hollywood. He and Pops roll me over the kitchen floor on that board, holding on to my hands.

I can’t tell you exactly what my first skateboard was, because that memory is buried in my childhood, like another kid’s recollection of his first rocking horse. Pops says I was around five years old when a friend sent us a set of the new urethane wheels by Cadillac and a pair of Chicago trucks—the metal mechanisms that a board sits on and that wheels ride under.

Hawaiian surfing legend Gerry Lopez was my idol at the time. I once saw a surf movie with Pops where it looked like the entire ocean was falling down around Lopez at Pipeline, and he was standing in the barrel as casually as if he was standing on the sidewalk, waiting for the light to change. In the movie, he rode a red board with a silver lightning bolt. Pops makes me a fiberglass skateboard, a miniature version of Lopez’s surfboard, red with a silver lightning bolt. The skateboard has a kicked-up nose like a surfboard and is turned down in the tail—something Pops thinks will work well for braking. I ride the board in reverse, so it works like a kicktail skateboard, something that won’t be invented for another few years.

I’m no older than six when several cute girls my age run over to my house, giggling in their floral bikinis, asking me to come out and skate. One of them stands guard to make sure there aren’t any cars coming while I bomb the hill, and the rest of them cheer me on as I speed past them. Girls cheering me on while I ride a skateboard—I can almost think that was some sort of premonition of things to come.

My first store-bought board is a G&S with OJ wheels. I love that board so much I keep it in my room, right next to my bed. One day I’m out playing hide-and-seek and stash that board in the bushes. When I return, it’s gone. That sucks big-time.

There’s no pro skateboarding yet; I’m just a little kid in search of big heroes. Aside from surfers, my influences aren’t skateboarders, but musicians and martial artists. I want to be Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page and blast out those big power chords of his. The only thing I want more than that is to be martial arts legend Bruce Lee. At an age when other kids are reading comic books, I have everything in Bruce Lee’s books underlined and even memorized. I take his sayings to heart—things like, “Be water, fast and fluid.” Since I can’t actually be Bruce Lee, I want to beat him and every other martial artist in the world, someday. My dad practices martial arts, and he drives me to the studio with him, where we do kung fu together.

Whenever there’s a new kung fu movie in town, we go to the Mar Vista Theater in Chinatown. We don’t just watch the movies; we absorb every frame in Bruce Lee’s pictures, sometimes watching them two or three times. Bruce Lee isn’t like all the other action movie heroes. He doesn’t tell his opponents what he’s going to do to them; he simply does it. By then it’s too late for them. He’s overwhelmingly fast, powerful, stylish, and confident—and that’s just how I’m going to be.

BRUCE LEE ON WHEELS

There aren’t many kids my age skateboarding in my neighborhood, but Aaron, the kid I smoked that first joint with, is one of them. Aaron “Fingers” Murray will become a legendary skateboarder, and one day he’ll own a skateboard company called Koping Killer.

We’ve always had a lot in common. Like me he’s part Asian, and his parents are really liberal. Both his parents attended Chouinard Art Institute with Pops. Aaron is adventurous and curious and desires to be the best at whatever he does. By the time we begin hanging out, his parents are separated and so are mine. Whenever we’re at one of our dads’ houses, we hang out together all day and long into the night. During the day we skate. At night we tear around the house, leaping over couches and chairs and playing games while our dads jam the blues on guitars and drink Rémy Martin cognac and smoke cigarettes and fat joints that we take hits from.

I gradually discover that a lot of parents who survived the ’60s carry that experience over as they experiment with unique ways of raising their kids and continue to use drugs. Smoking weed is no big deal to them; they consider it harmless. Such parents are different than most parents today—but even back then, nobody is as different as Pops. He’s radical in his approach to everything, especially raising a child, even for those times.

Initially I think all parents are like mine. When I visit most other kids’ houses, however, I see that it isn’t so. Most kids have to hide when they get high. They live in massive houses crawling with brothers and sisters. Nobody plays or even talks together, and they all seem to hate each other. The kids hang out quietly in their separate rooms, probably smoking weed, while their parents politely talk about things not worth the words.

When I’m with my mom or my dad, they don’t hide a thing from me, and they let me and my friends in on the discussion if we’re interested. They tell me that if I want to be like Jimmy Page or Bruce Lee, all it takes is practice. Not like, “Get real, kid—nobody will ever achieve that, much less you.” As a little kid you immediately think either I can or I can’t. All I ever hear is “You can.” Maybe it would be good to hear what I can’t or shouldn’t do once in a while, but that never happens in our family.

Aaron and I jump around the house until we’re too tired to stay awake, playing like most other eight-year-olds, except that we’re stoned out of our minds on the best weed a person can get. Being high makes it easy to imagine that we’re Bruce Lee, throwing around nunchakus, acting it all out, jumping from one table to another, daring each other to jump further, saying, “Okay, I’ll bet you can’t do that.” Once we both land a jump, we pull the tables wider and wider apart, leaping further and further. When we finally miss a jump, we know just how far we can or can’t go. (It’s like Clint Eastwood says: “A man’s gotta know his limitations.”) We’re totally free to push the limits of possibility as we become crazy acrobatic daredevils, something that will soon translate into our skateboarding.

There are times we’re maybe thirty feet up in some tree, saying, “I’m gonna jump from here and land on that bush.” When we suddenly realize how high up we are, occasionally we’re like, “All right, I can’t do that after all,” but usually we don’t back down. In the martial arts movies people say things like, “Your tiger claw is no match for my praying mantis.” Once skateboarding gets us in its grip, that becomes, “My ollie is higher than your ollie.” We want to do things our own way, be the best, jump the furthest, and reign supreme as king of the mountain.

DEEPER AND HIGHER

Nobody stays together forever in L.A., and my parents are no exception. They split up around the time I’m eight years old. When I get older, Pops eventually tells me that my mom once threw all his possessions out the window, onto the street. He doesn’t mention what led up to that, but knowing him, I suspect it was at least partially his fault. It always takes two, right?

MY FATHER. THE ARTIST EVERYBODY CALLED POPS. HOSOI FAMILY COLLECTION.

He tries to shield me from things like that, and I guess it works, because I don’t remember things being too bad. There’s a lot of arguing at home, but nothing crazy or violent or anything—just the day-to-day disagreements that for some people lead to court proceedings and for others, like my parents, separation. They never seem mad at each other after their separation; they simply quit living together. As far as I can tell they’re close friends and everybody’s happy. They never do get divorced except as a formality, years later, so my mom can remarry. Together or apart, they are always there for me.

You might think I got into drugs as a result of my upbringing or my parents’ breakup, but that’s not true. As a child I never had that deep longing for my parents to get back together that you sometimes hear about, and I never felt that something was broken or missing in my life. I’m the type that would have found drugs whether my parents were together or not, even if they didn’t smoke weed, which is hard to imagine. When you feel entitled, as I did, you’re never satisfied. You want more. In my case, that meant running deeper and getting higher.

THICKER THAN WATER

My father’s full name is Ivan Toyo Hosoi. He’s full-blooded Japanese. He was born on Oahu on September 26, 1942. As a child he stole the family car and drove it through Honolulu, getting out and peering into various bars in search of his dad. Even after being punished, he continued taking the car to town now and then.

Eventually he was shipped off to the “Big Island” of Hawaii to work on the Parker Ranch as a cowboy. Because of being sent away, he thought for a long time that he had been adopted. That hurt, but being Japanese in the 1940s, Pops also suffered racism, and one of his uncles was actually sent to an internment camp in California.

My mom, who passed away last year, was part Hawaiian; she was born on Maui. Before she married my father, her name was Bonnie Puamana Cummings.

I was born Christian Rosha Hosoi in Good Shepherd Hospital in Los Angeles on October 5, 1967. Pops once told a friend that my name represented three religions: Christian for Christianity, Rosha for Judaism, and Hosoi for Buddhism. I don’t know, but it sounds good.

In 1974, when I’m six years old, the family is still together, and we move to Oahu. Pops has been a surfer since the 1950s, so we go to the beach every day, all day, whenever I’m not in school. I mess around, riding some little waves, but I never really hook up with surfing the way he does.

After a year on Oahu we move back to L.A. because the teaching job he was promised at the University of Hawaii doesn’t pan out. The other reason we move is that I have a bad kidney infection, made worse by all the mosquitoes that forever buzz the Hawaiian Islands. The first house we rent in California is in Beachwood Canyon, Hollywood. Later we rent a big studio on Washington Boulevard and Vermont Avenue, in L.A.’s Koreatown.

My parents first moved from Hawaii to L.A. before I was born so that Pops could refine his art skills at Chouinard. My mom helped put him through school and he ended up transferring to and graduating from U.C. Berkeley, where he received a master’s degree in fine art.

Picture us in Berkeley in the late ’60s: I’m being pushed in a stroller when the Berkeley riots go down. How crazy is that? I’m already a rebel at two years old!

Besides being birthed into rebellion, I’m born into music and art. Pops often has his paintings displayed in a gallery where he also plays music. When I get sleepy, he simply lays me down in the soft velvet of his guitar case, behind the amps, with nothing but my legs sticking out. When he isn’t working on his own projects, he assists famed artists Sam Francis and Ron Davis. Whatever those guys want he builds for them. At other times he does his immaculate custom woodwork on people’s mansions.

From a young age Pops whispers in my ear that surfing and skateboarding are art forms, and I learn to see all creative expression from an artistic point of view. I want to express my art through skateboarding and do things no skateboarder has ever done before. I want to fly higher than anyone ever has and put on a show while doing it.

While Pops is a free spirit, my mother is a lot more regimented, and I can honestly say I’ve never met anyone like her. She has a strong family foundation, embodied in the aloha spirit of Hawaii, and is just over the top with things like family reunions and sending out cards for everyone’s birthday. She dresses right for every occasion and is well spoken, business-minded, and organized. Even as rambunctious and rebellious as I am, when she says, “Christian, you gotta keep your head on straight,” I respond right away.

When we move back to L.A. from Hawaii, my mom works as a secretary for a big company in Beverly Hills. She tells me to do my homework, and she’s probably the only person in the world who could get me to do it. But she isn’t all business; she’s also a ’60s girl, into art, wine, and weed. A friend of mine remembers sleeping over once when we were young teenagers. He says that I was yelling at my mom to find my roaches and she told me where they were. He claims he saw her take a hit from a joint before walking out the door to go to work. Like most kids of the time, he’d never seen adults be so casual about weed.

Like Pops, my mom really doesn’t care so much what I do. Unlike Pops, she insists that I keep things together when I do them. I learn about business and working with people who are different from me, from her.

My parents teach me a lot about life, but in skateboarding I’m on my own, at least for the time being. There are no videos to rewind again and again; all we have are the skaters we see on the streets and the still photos we cut from the mags. We memorize those stills and have to imagine what happened before and after the shots were taken. We study each shot so carefully that we can tell you what boards and wheels everyone rides. We know who took the shot, where it was taken, and more often than not who’s standing in the background. Having only magazines for reference stimulates the imagination far more than any video ever could.

In 1978 I’m eleven years old and Pops and I build a ramp in our backyard. Aaron also builds a ramp in his father’s warehouse, and together they move that to my backyard. Now we have a bank ramp and a quarter-pipe right there at home, any time we want. I make it sound like we build them, but of course our dads are the ones who do all the work. We act like we’re helping, which really amounts to nothing more than telling them to hurry up.

LOOKING INTO MY FUTURE. HOSOI FAMILY COLLECTION.