Chapter 6

My New School

My day started before the rooster crowed. I washed my face and raked a brush through my hair. Didn’t do much good. My hair sprung out like tree branches from a night of head tossing on a feather pillow. When I tried to brush it out, my hair pulled, so I figured I’d tie it all up in a ponytail. My day was off to a bad start. Another thing I figured was that the bad would turn to worse when I set foot in my new school.

I was real careful how I moved, making sure I kept my back turned away from everybody. When I met Mom or Grandma, I backed up and let them pass. My plan worked until that brat of a brother of mine stuck his nose into a place it didn’t belong—my business.

“Mom, Grace Ann’s got a rat’s nest in the back of her head,” Johnny bigmouthed. Then he bent over with a belly laugh, pointed at my head and squeaked like a rat.

I pitched him a squint-eyed look, but he kept on pointing and cackling.

Mom said, “Grace, let me see your hair in back.”

That’s all it took. Mom grabbed a brush and swiped it through my hair. Mom didn’t quit until she had untangled the wad. Finally, she kissed the top of my head and declared that my hairdo did me proud.

After I pulled on a green-and-white checked dress and yellow sweater, I stuck my socked feet into my patent leather shoes and walked into the kitchen. I sat down to a bowl of cornflakes Grandma had set out for me. Most of the time I scarfed down a bowl of cornflakes and loaded up on seconds, but today, my tummy jiggled and wiggled from my nerves. I crammed a spoonful of milk and flakes into my mouth, but somehow I didn’t feel like eating.

Grandma walked over and patted me on the shoulder.

Johnny charged through the kitchen, all smiles and jabbering. “Mom said I’ll make new friends at school.”

“I don’t want new friends, Johnny,” I told him. “I want my old friends. My old school. My old teacher. My old house.” Tears dribbled down my face. When Johnny saw my tears, his eyes clouded up and rained too.

Mom came into the kitchen and told me I shouldn’t upset my brother. “He was looking forward to the new school, and now you’ve got him worried,” she snapped at me.

I didn’t mean to upset Johnny. Or Mom. I stomped out of the kitchen and yelled, “Nobody cares how I feel!” I missed my dad and how he would always listen to how I was feeling or what I had to say.

Mom followed me. She wrapped her arms around me in a big hug and said everything would be all right. I could tell by the way she said it that she didn’t really mean that everything would be all right. What Mom meant was that I would have to live with my new life and my new school.

I raced outside to kiss Spot goodbye before school. “I’ll miss you today. I know you didn’t want to move here, but remember, we’ve got to have gumption.”

Spot yipped. In dog talk that meant, “I may have to move, but I don’t have to like it.”

“I wish you could go to school with me,” I whispered.

Spot drooped his tail as if to say he was sorry he couldn’t go.

I looked at my sweet mutt, and the words Grandpa used to say burst out of my mouth: “If wishes were fishes, we’d have a fry.”

Spot whined to agree.

“You’re right, wishing won’t make it happen,” I told Spot. “The wish fairy must be on vacation.”

A few minutes later, Mom walked Johnny and me to our new school. Each grade had a separate room. Johnny was in first grade; I was in sixth. That meant Johnny was in one room and I was in another. Phooey. I wouldn’t know one person in school. Double phooey. Johnny would be scared. Triple phooey. My brother was a big-time pest, but I didn’t want him terrified the way I felt.

Mom introduced us to his teacher, Mrs. Short. “This is my daughter, Grace Ann, and my son, Johnny.”

Mrs. Short welcomed us and said she was glad to have Johnny in her class.

Mom hugged Johnny. We stood in the room a minute longer as Mom talked with his teacher. I snagged a lock of my hair and twisted it as I looked at my brother. His eyes searched the classroom, but he didn’t seem scared or upset. How could he not be upset? How could he not have a hole in the bottom of his stomach? How could he not be shaking?

Mrs. Short reached for Johnny’s hand and led him over to a group of students. They began talking with him, and he talked back with a big grin on his face, as if he actually liked being here, surrounded by strangers. My brother is as weird as they come.

Mom and I walked down to the sixth-grade classroom. Mrs. Martin, my teacher, introduced herself. She and Mom talked for a minute or two as my eyes swept across all the unfamiliar faces. I turned back around and saw that Mom had left.

A lump made a home in my throat like the one I had when Daddy left. I swallowed hard and told myself to be brave, the way Daddy wanted me to be. The stubborn lump hung in there, but the tears didn’t spill over like I was afraid they would. My eyes sort of watered up is all.

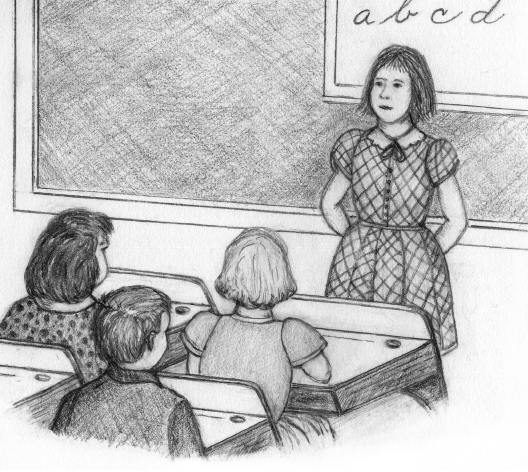

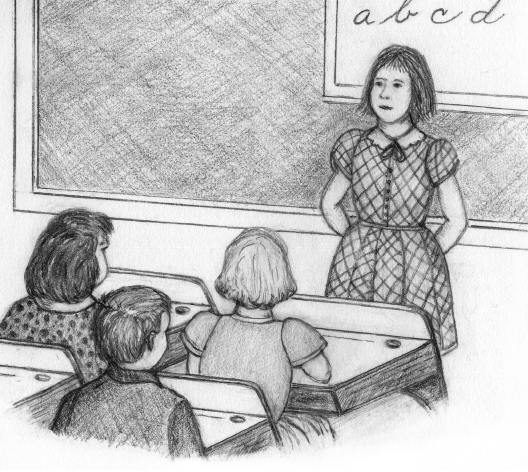

Mrs. Martin introduced me to the class. The students stood, one by one, eyes pasted on me, and told me their names. My toes began to wiggle, but I willed them to stop. What I really wanted to do was run to a corner, ball up and hide. On top of that, I could not remember the name of one student.

The teacher led me to a desk and told me it was mine; then she opened a book and asked me to read for her. I knew most of the words, all but three. After I read, she handed me an arithmetic book.

“Turn to page seventy-five, please, Grace,” she said in a kind voice, as if she knew I was scared clear to the bone. I opened the book, and she pointed to a reading problem. I read the problem about a farmer who had a load of apples to divide into bushels and pecks.

“Show me how you would solve the problem,” Mrs. Martin said.

I opened my notebook, grabbed a pencil and worked the long division problem. When I finished, Mrs. Martin patted me on the shoulder and said, “Good work.” She asked me to work all the problems on the page, and she moved over two rows to work with another student.

As I tackled the next problem, the girl behind me whispered in my ear, “Teacher’s pet.” I turned around to see who was talking to me and saw the biggest girl I had ever seen in sixth grade. She squinted her face into a bunched-up frown and whispered, “Showoff.”

I scooted back around in my seat. As I multiplied and divided numbers, a sharp pencil jabbed me in the shoulder. When I turned back around to see if the girl had jabbed me by accident, she stuck her tongue out at me. Like a bear, she was big and grumpy with sharp claws. I’d never actually seen a bear or heard one growl, but she reminded me of a grizzly, all the same. For certain, her pencils were as sharp as claws.

I didn’t know what to do. Everyone in front of me was busy working. So were the students on both sides of me. The only two in the whole classroom not doing what they were supposed to were Miss Bear Claws and me. How could this day get any worse? I started working on the next problem. Before I was half finished, pain throbbed my right shoulder from another pencil jab. I tried to ignore her, but pain has a way of grabbing my attention.