INTRODUCTION

I did a great deal of reading about Sunday in the Park with George before I sat down to write this introduction. I discovered that masses of articles, interviews, and essays had been written about this landmark musical since its opening on Broadway in April of 1984. I realized that I had nothing especially new to say about the show—Sondheim’s use of “chord clusters,” Lapine’s avoidance of Latin root words and contractions in an effort to simulate 19th Century French speech patterns, the trials and tribulations of getting the second act into shape and so on—all of these have been well documented.

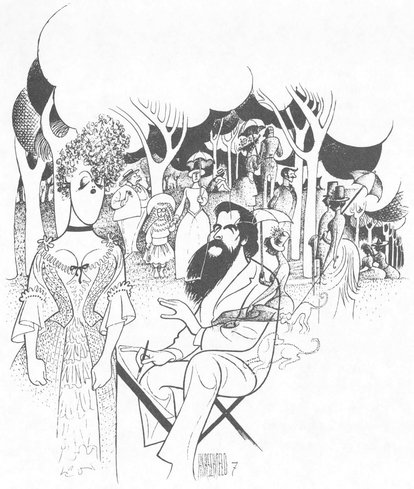

I then did something you are about to do: I read the text. I was deeply moved. I found the sheer audacity of the idea of the show amazing. Imagine a musical in which the first act breathes dramatic life into one of the great works of late 19th Century painting. Then try to top Act One with a second act that takes place a hundred years later and deals satirically with the contemporary art world and then goes on to chronicle the sadness of a young artist who has lost his way in it.

Sunday in the Park with George is a very personal show and so it seems appropriate that this introduction be personal too. The show meant a great deal to its creators, indeed to all who worked on it. My presence in these pages can be explained because it was my theater, Playwrights Horizons, that commissioned the piece initially from James Lapine and then gave it its first home and its first production prior to the run on Broadway. My recollections of a hectic, exhilarating time are happy ones, although Playwrights Horizons had never produced a musical on such a large scale before. Enormous amounts of time and energy went into organizing ourselves to go into rehearsal for a piece that we knew very little about—there was a first act with a number of songs and a sketch of a second act. That was it.

People would say to me, “Why are you putting on such an elaborate production of something that is only half-written?” Indeed, though we called the event a “workshop” and believe me it was a workshop, we had to raise a great deal of money to do it and a lot of that money went into costumes and sets. It seems to me, as I look back, that we were always having benefits and that I was always lugging around color reproductions of La Grande Jatte to show to prospective donors! In any event, I believed that if you were doing a show about vision and creation and if the event was the recreation of a painting of people in a French park in 1884, you couldn’t effectively “workshop” the visuals with women in rehearsal skirts, men in leotards, and a black velour surround. You had to do it full out or not at all.

One of the highlights of our production and of the show turned out to be the end of Act One when Seurat artfully arranges the various groups of squabbling Parisians into a perfect and harmonious picture. There was something about the scale of the final image that related beautifully to the dimensions of our small theater space. When everyone on stage sang the final three “Sundays,” and the horn played, and the picture was complete and frozen, and the blank canvas that we used as a show curtain came in—well, it was a perfect blend for the ear and the eye. And most nights the audience (even some of the ancient ones who occasionally nodded off) would cheer and stomp and scream their approval. Though the show was infinitely better and more complete on Broadway, I always felt that the Act One finale worked best at Playwrights Horizons. It was literally and beautifully overpowering.

When we began performances in July of 1983, we had most of a first act (“Everybody Loves Louis,” “Beautiful,” and “Finishing the Hat” were added during our run) and hardly any Act Two. So we decided to only perform the first act—it was, after all, a fairly complete unit—and to add Act Two when the authors were ready. We hoped our loyal subscription audience would accept this in the spirit of a “work-in-progress,” and they did. Part of the reason they did had to do with the speeches I felt I should give before each performance, explaining what we were up to in as inspiring a fashion as possible and then casually mentioning that Act Two wasn’t quite ready and that we were sparing them great torment by not performing it that night. Actually, we only performed it three times!

People who know me know that I’ll do anything to avoid having to speak in public, but such was my fate those muggy summer nights in 1983. When I look back on it, though, I wonder if I was able to get the audience on our side for no other reason than they felt sorry for me because I appeared to be so nervous. Ira Weitzman, our Musical Theater Program Director, was much more at ease when he had to “make the speech,” and by the end of the run would stroll up to the apron of the stage, wearing shorts and a T-shirt, and sort of say, “Hi, folks, guess what? No Act Two tonight, but you’re gonna love Act One!”

The best speech night and one of the great nights of my theater life was the night “Finishing the Hat” went into the show. Mandy Patinkin had learned the music but wanted to hold onto the printed lyrics. I explained in the speech that this night was something special because a new song was being added and that Seurat would, at one point, be holding some sheets of music. An audience loves being in on something for the first time. When Mandy picked up the music and sang the song—so carefully and lovingly—and the song turned out to be deeply personal, layered with meaning and metaphor, and beautifully spun out, we all felt that we had entered musical theater heaven. And we had. Even today I run into people who claim they saw the show the night “Finishing the Hat” went in and that it was a rare and special occasion.

Playwrights Horizons believes that opportunities create and sustain artists, and we felt that the best thing we could do for Sondheim and Lapine was to step back and give them a chance to discover their show. I wanted them to be free to do what they wanted without any kind of management pressure, without any kind of publicity or review, and most of all, without any kind of fear. I felt that they were onto something important, and I knew that the collaboration between the two men was new and at an early and delicate stage. Stephen Sondheim was working with a different partner for the first time in years, and he had never really worked in a non-profit situation in New York. Everyone at Playwrights Horizons wanted him to find us at our best and to work happily under a different system of creating shows than the traditional Broadway one.

Because I am writing this in June of 1990 when the National Endowment for the Arts in particular and non-profit arts subsidy in general are under attack, I want to note that the creative freedom that Sondheim and Lapine were given at my theater and the good advantage they took of it is directly due to funding dollars. If subsidy is taken away from theaters, especially those that deal with new, experimental, untried work, these theaters will fade away. And if this happens, there will be no venue for new work at all and any sort of new American theater will simply disappear. Artists will no longer have artistic homes away from the marketplace. What I’m trying to say is that had it not been for subsidy there would be no Playwrights Horizons and quite possibly no Sunday in the Park with George.

A month or so after the show closed at Playwrights Horizons, I flew to Chicago to go to the Art Institute where Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte hangs. I probably should have done this at the outset instead of at the end, because as I walked up the steps and got closer and closer to the treasured painting, I finally understood what it was the two authors were doing. In front of me, and massively so, was an extraordinary composition of shapes and colors and brushstrokes that reflected the work of a man obsessed with his art. Even to a jaded, late 20th Century New Yorker, who had seen countless reproductions of La Grande Jatte and had just done a show about it, the painting was startling and lovely and upsetting and inspiring. I stood and stared for hours, much as I imagine the authors did, until I felt I was both outside the painting and inside, and definitely part of it. There were many areas and people on the huge canvas that were not represented in the musical, and I wondered who they had been and why they were there. It must have been at this point of heightened curiosity and emotion that Lapine and Sondheim began their own search for a new form inspired by the legacy of an extraordinary artist from another century.

I am very proud of the part Playwrights Horizons played in the development of Sunday in the Park with George. I think the show represents what is best about the American musical theater, and it certainly came out of what is best about the non-profit theater.

André Bishop

Playwrights Horizons

June 1990

P.S. The two best and most detailed accounts of the partnership that created Sunday in the Park with George are to be found in the 2nd edition of Craig Zadan’s Sondheim and Co. (Harper and Row) and Michiko Kakutani’s article for The New York Times, reprinted in her book The Poet at the Piano (New York Times Books).

Bernadette Peters

Bernadette Peters and Mandy Patinkin