THE years of underground burrowings, of secret or disguised preparations, were now over, and Hitler at length felt himself strong enough to make his first open challenge. On March 9, 1935, the official constitution of the German Air Force was announced, and on the 16th it was declared that the German Army would henceforth be based on national compulsory service. The laws to implement these decisions were soon promulgated, and action had already begun in anticipation. The French Government, who were well informed of what was coming, had actually declared the consequential extension of their own military service to two years a few hours earlier on the same momentous day. The German action was an open formal affront to the treaties of peace upon which the League of Nations was founded. As long as the breaches had taken the form of evasions or calling things by other names, it was easy for the responsible victorious Powers, obsessed by pacifism and preoccupied with domestic politics, to avoid the responsibility of declaring that the Peace Treaty was being broken or repudiated. Now the issue came with blunt and brutal force. Almost on the same day the Ethiopian Government appealed to the League of Nations against the threatening demands of Italy. When, on March 24, against this background, Sir John Simon with the Lord Privy Seal, Mr. Eden, visited Berlin at Hitler’s invitation, the French Government thought the occasion ill-chosen. They had now themselves at once to face, not the reduction of their Army, so eagerly pressed upon them by Mr. MacDonald the year before, but the extension of compulsory military service from one year to two. In the prevailing state of public opinion this was a heavy task. Not only the Communists but the Socialists had voted against the measure. When M. Léon Blum said, “The workers of France will rise to resist Hitlerite aggression,” Thorez replied, amid the applause of his Soviet-bound faction, “We will not tolerate the working classes being drawn into a so-called war in defence of Democracy against Fascism.”

The United States had washed their hands of all concern with Europe, apart from wishing well to everybody, and were sure they would never have to be bothered with it again. But France, Great Britain, and also—decidedly—Italy, in spite of their discordances, felt bound to challenge this definite act of treaty-violation by Hitler. A Conference of the former principal Allies was summoned under the League of Nations at Stresa, and all these matters were brought to debate.

There was general agreement that open violation of solemn treaties, for the making of which millions of men had died, could not be borne. But the British representatives made it clear at the outset that they would not consider the possibility of sanctions in the event of treaty-violation. This naturally confined the Conference to the region of words. A resolution was passed unanimously to the effect that “unilateral”—by which they meant one-sided—breaches of treaties could not be accepted, and the Executive Council of the League of Nations was invited to pronounce upon the situation disclosed. On the second afternoon of the Conference Mussolini strongly supported this action, and was outspoken against aggression by one Power upon another. The final declaration was as follows:

The three Powers, the object of whose policy is the collective maintenance of peace within the framework of the League of Nations, find themselves in complete agreement in opposing, by all practicable means, any unilateral repudiation of treaties which may endanger the peace of Europe, and will act in close and cordial collaboration for this purpose.

The Italian Dictator in his speech had stressed the words “peace of Europe”, and paused after “Europe” in a noticeable manner. This emphasis on Europe at once struck the attention of the British Foreign Office representatives. They pricked up their ears, and well understood that while Mussolini would work with France and Britain to prevent Germany from rearming he reserved for himself any excursion in Africa against Abyssinia on which he might later resolve. Should this point be raised or not? Discussions were held that night among the Foreign Office officials. Everyone was so anxious for Mussolini’s support in dealing with Germany that it was felt undesirable at that moment to warn him off Abyssinia, which would obviously have very much annoyed him. Therefore the question was not raised; it passed by default, and Mussolini felt, and in a sense had reason to feel, that the Allies had acquiesced in his statement and would give him a free hand against Abyssinia. The French remained mute on the point, and the Conference separated.

In due course, on April 15–17, the Council of the League of Nations examined the alleged breach of the Treaty of Versailles committed by Germany in decreeing universal compulsory military service. The following Powers were represented on the Council: the Argentine Republic, Australia, Great Britain, Chile, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, France, Italy, Mexico, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Turkey, and the U.S.S.R. All voted for the principle that treaties should not be broken by “unilateral” action, and referred the issue to the Plenary Assembly of the League. At the same time the Foreign Ministers of the three Scandinavian countries, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, being deeply concerned about the naval balance in the Baltic, also met together in general support. In all nineteen countries formally protested. But how vain was all their voting without the readiness of any single Power or any group of Powers to contemplate the use of FORCE, even in the last resort!

Laval was not disposed to approach Russia in the firm spirit of Barthou. But in France there was now an urgent need. It seemed, above all, necessary to those concerned with the life of France to obtain national unity on the two years’ military service which had been approved by a narrow majority in March. Only the Soviet Government could give permission to the important section of Frenchmen whose allegiance they commanded. Besides this, there was a general desire in France for a revival of the old alliance of 1895, or something like it. On May 2, 1935, the French Government put their signature to a Franco-Soviet pact. This was a nebulous document guaranteeing mutual assistance in the face of aggression over a period of five years.

To obtain tangible results in the French political field Laval now went on a three days’ visit to Moscow, where he was welcomed by Stalin. There were lengthy discussions, of which a fragment not hitherto published may be recorded. Stalin and Molotov were of course anxious to know above all else what was to be the strength of the French Army on the Western Front: how many divisions? what period of service? After this field had been explored Laval said: “Can’t you do something to encourage religion and the Catholics in Russia? It would help me so much with the Pope.” “Oho!” said Stalin. “The Pope! How many divisions has he got?” Laval’s answer was not reported to me; but he might certainly have mentioned a number of legions not always visible on parade. Laval had never intended to commit France to any of the specific obligations which it is the habit of the Soviet to demand. Nevertheless he obtained a public declaration from Stalin on May 15 approving the policy of national defence carried out by France in order to maintain her armed forces at the level of security. On these instructions the French Communists immediately turned about and gave vociferous support to the defence programme and the two years’ service. As a factor in European security the Franco-Soviet Pact, which contained no engagements binding on either party in the event of German aggression, had only limited advantages. No real confederacy was achieved with Russia. Moreover, on his return journey the French Foreign Minister stopped at Cracow to attend the funeral of Marshal Pilsudski. Here he met Goering, with whom he talked with much cordiality. His expressions of distrust and dislike of the Soviets were duly reported through German channels to Moscow.

Mr. MacDonald’s health and capacity had now declined to a point which made his continuance as Prime Minister impossible. He had never been popular with the Conservative Party, who regarded him, on account of his political and war records and Socialist faith, with long-bred prejudice, softened in later years by pity. No man was more hated, or with better reason, by the Labour-Socialist Party, which he had so largely created and then laid low by what they viewed as his treacherous desertion in 1931. In the massive majority of the Government he had but seven party followers. The disarmament policy to which he had given his utmost personal efforts had now proved a disastrous failure. A General Election could not be far distant, in which he could play no helpful part. In these circumstances there was no surprise when, on June 7, it was announced that he and Mr. Baldwin had changed places and offices and that Mr. Baldwin had become Prime Minister for the third time. The Foreign Office also passed to another hand. Sir Samuel Hoare’s labours at the India Office had been crowned by the passing of the Government of India Bill, and he was now free to turn to a more immediately important sphere. For some time past Sir John Simon had been bitterly attacked for his foreign policy by influential Conservatives closely associated with the Government. He now moved to the Home Office, with which he was well acquainted, and Sir Samuel Hoare became Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs.

At the same time Mr. Baldwin adopted a novel expedient. He appointed Mr. Anthony Eden to be Minister for League of Nations Affairs. Eden had for nearly ten years devoted himself almost entirely to the study of foreign affairs. Taken from Eton at eighteen to the World War, he had served for four years with distinction in the 60th Rifles through many of the bloodiest battles, and risen to the position of Brigade-Major, with the Military Cross. He was to work in the Foreign Office with equal status to the Foreign Secretary and with full access to the dispatches and the departmental staff. Mr. Baldwin’s object was no doubt to conciliate the strong tide of public opinion associated with the League of Nations Union by showing the importance which he attached to the League and to the conduct of our affairs at Geneva. When about a month later I had the opportunity of commenting on what I described as “the new plan of having two equal Foreign Secretaries”, I drew attention to its obvious defects.

While men and matters were in this posture a most surprising act was committed by the British Government. Some at least of its impulse came from the Admiralty. It is always dangerous for soldiers, sailors, or airmen to play at politics. They enter a sphere in which the values are quite different from those to which they have hitherto been accustomed. Of course they were following the inclination or even the direction of the First Lord and the Cabinet, who alone bore the responsibility. But there was a strong favourable Admiralty breeze. There had been for some time conversations between the British and German Admiralties about the proportions of the two Navies. By the Treaty of Versailles the Germans were not entitled to build more than six armoured ships of 10,000 tons, in addition to six light cruisers not exceeding 6,000 tons. The British Admiralty had recently found out that the last two pocket-battleships being constructed, the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau, were of a far larger size than the Treaty allowed, and of a quite different type. In fact, they turned out to be 26,000-ton light battle-cruisers, or commerce-destroyers of the highest class, and were to play a significant part in the Second World War.

In the face of this brazen and fraudulent violation of the Peace Treaty, carefully planned and begun at least two years earlier (1933), the Admiralty actually thought it was worth while making an Anglo-German Naval Agreement. His Majesty’s Government did this without consulting their French ally or informing the League of Nations. At the very time when they themselves were appealing to the League and enlisting the support of its members to protest against Hitler’s violation of the military clauses of the Treaty they proceeded by a private agreement to sweep away the naval clauses of the same Treaty.

The main feature of the agreement was that the German Navy should not exceed one-third of the British. This greatly attracted the Admiralty, who looked back to the days before the First World War when we had been content with a ratio of sixteen to ten. For the sake ofthat prospect, taking German assurances at their face value, they proceeded to concede to Germany the right to build U-boats, explicitly denied to her in the Peace Treaty. Germany might build 60 per cent. of the British submarine strength, and if she decided that the circumstances were exceptional she might build to 100 per cent. The Germans, of course, gave assurances that their U-boats would never be used against merchant ships. Why, then, were they needed? For, clearly, if the rest of the agreement was kept, they could not influence the naval decision, so far as warships were concerned.

The limitation of the German Fleet to a third of the British allowed Germany a programme of new construction which would set her yards to work at maximum activity for at least ten years. There was therefore no practical limitation or restraint of any kind imposed upon German naval expansion. They could build as fast as was physically possible. The quota of ships assigned to Germany by the British project was, in fact, far more lavish than Germany found it expedient to use, having regard partly no doubt to the competition for armour-plate arising between warship and tank construction. Hitler, as we now know, informed Admiral Raeder that war with England would not be likely till 1944–45. The development of the German Navy was therefore planned on a long-term basis. In U-boats alone did they build to the full paper limits allowed. As soon as they were able to pass the 60 per cent. limit they invoked the provision allowing them to build to 100 per cent. and fifty-seven were actually constructed when war began.

In the design of new battleships the Germans had the further advantage of not being parties to the provisions of the Washington Naval Agreement or the London Conference. They immediately laid down the Bismarck and the Tirpitz, and, while Britain, France, and the United States were all bound by the 35,000 tons limitation, these two great vessels were being designed with a displacement of over 45,000 tons, which made them, when completed, certainly the strongest vessels afloat in the world.

It was also at this moment a great diplomatic advantage to Hitler to divide the Allies, to have one of them ready to condone breaches of the Treaty of Versailles, and to invest the regaining of full freedom to rearm with the sanction of agreement with Britain. The effect of the announcement was another blow at the League of Nations. The French had every right to complain that their vital interests were affected by the permission accorded by Great Britain for the building of U-boats. Mussolini saw in this episode evidence that Great Britain was not acting in good faith with her other allies, and that, so long as her special naval interests were secured, she would apparently go to any length in accommodation with Germany, regardless of the detriment to friendly Powers menaced by the growth of the German land forces. He was encouraged by what seemed the cynical and selfish attitude of Great Britain to press on with his plans against Abyssinia. The Scandinavian Powers, who only a fortnight before had courageously sustained the protest against Hitler’s introduction of compulsory service in the German Army, now found that Great Britain had behind the scenes agreed to a German Navy which, though only a third of the British, would within this limit be master of the Baltic.

Great play was made by British Ministers with a German offer to co-operate with us in abolishing the submarine. Considering that the condition attached to it was that all other countries should agree at the same time, and that it was well known there was not the slightest chance of other countries agreeing, this was a very safe offer for the Germans to make. This also applied to the German agreement to restrict the use of submarines so as to strip submarine warfare against commerce of inhumanity. Who could suppose that the Germans, possessing a great fleet of U-boats and watching their women and children being starved by a British blockade, would abstain from the fullest use of that arm? I described this view as “the acme of gullibility”.

Far from being a step towards disarmament, the agreement, had it been carried out over a period of years, would inevitably have provoked a world-wide development of new warship-building. The French Navy, except for its latest vessels, would require reconstruction. This again would react upon Italy. For ourselves, it was evident that we should have to rebuild the British Fleet on a very large scale in order to maintain our three to one superiority in modern ships. It may be that the idea of the German Navy being one-third of the British also presented itself to our Admiralty as the British Navy being three times the German. This perhaps might clear the path to a reasonable and overdue rebuilding of our Fleet. But where were the statesmen?

This agreement was announced to Parliament by the First Lord of the Admiralty on June 21, 1935. On the first opportunity, I condemned it: What had in fact been done was to authorise Germany to build to her utmost capacity for five or six years to come.

Meanwhile in the military sphere the formal establishment of conscription in Germany on March 16, 1935, marked the fundamental challenge to Versailles. But the steps by which the German Army was now magnified and reorganised are not of technical interest only. The name Reichswehr was changed to that of Wehrmacht. The Army was to be subordinated to the supreme leadership of the Fuehrer. Every soldier took the oath, not, as formerly, to the Constitution, but to the person of Adolf Hitler. The War Ministry was directly subordinated to the orders of the Fuehrer. A new kind of formation was planned—the Armoured, or “Panzer”, Division, of which three were soon in being. Detailed arrangements were also made for the regimentation of German youth. Starting in the ranks of the Hitler Youth, the boyhood of Germany passed at the age of eighteen on a voluntary basis into the S.A. for two years. Service in the Work Battalions or Arbeitsdienst became a compulsory duty on every male German reaching the age of twenty. For six months he would have to serve his country, constructing roads, building barracks, or draining marshes, thus fitting him physically and morally for the crowning duty of a German citizen, service with the armed forces. In the Work Battalions the emphasis lay upon the abolition of class and the stressing of the social unity of the German people; in the Army it was put upon discipline and the territorial unity of the nation.

The gigantic task of training the new body and of expanding the cadres now began. On October 15, 1935, again in defiance of the clauses of Versailles, the German Staff College was reopened with formal ceremony by Hitler, accompanied by the chiefs of the armed services. Here was the apex of the pyramid, whose base was now already constituted by the myriad formations of the Work Battalions. On November 7, the first class, born in 1914, was called up for service: 596,000 young men to be trained in the profession of arms. Thus at one stroke, on paper at least, the German Army was raised to nearly 700,000 effectives.

It was realised that after the first call-up of the 1914 class, in Germany as in France, the succeeding years would bring a diminishing number of recruits, owing to the decline in births during the period of the World War. Therefore in August 1936 the period of active military service in Germany was raised to two years. The 1915 class numbered 464,000, and with the retention of the 1914 class for another year the number of Germans under regular military training in 1936 was 1,511,000 men. The effective strength of the French Army, apart from reserves, in the same year was 623,000 men, of whom only 407,000 were in France.

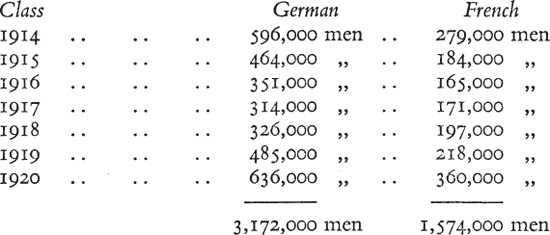

The following figures, which actuaries could foresee with some precision, tell their tale:

TABLE OF THE COMPARATIVE FRENCH AND GERMAN FIGURES FOR THE CLASSES BORN FROM 1914 TO 1920, AND CALLED UP FROM 1934 TO 1940 Until these figures became facts as the years unfolded they were still but warning shadows. All that was done up to 1935 fell far short of the strength and power of the French Army and its vast reserves, apart from its numerous and vigorous allies. Even at this time a resolute decision upon the authority, which could easily have been obtained, of the League of Nations might have arrested the whole process. Germany could either have been brought to the bar at Geneva and invited to give a full explanation and allow inter-Allied missions of inquiry to examine the state of her armaments and military formations in breach of the Treaty, or, in the event of refusal, the Rhine bridgeheads could have been reoccupied until compliance with the Treaty had been secured, without there being any possibility of effective resistance or much likelihood of bloodshed. In this way the Second World War could have been at least delayed indefinitely. Many of the facts and their whole general tendency were well known to the French and British Staffs, and were to a lesser extent realised by the Governments. The French Government, which was in ceaseless flux in the fascinating game of party politics, and the British Government, which arrived at the same vices by the opposite process of general agreement to keep things quiet, were equally incapable of any drastic or clear-cut action, however justifiable both by treaty and by common prudence.