ASTONISHMENT was world-wide when Hitler’s crashing onslaught upon Poland and the declarations of war upon Germany by Britain and France were followed only by a prolonged and oppressive pause. Mr. Chamberlain in a private letter published by his biographer described this phase as “Twilight War;* and I find the expression so just and expressive that I have adopted it as the title for this period. The French armies made no attack upon Germany. Their mobilisation completed, they remained in contact motionless along the whole front. No air action, except reconnaissance, was taken against Britain; nor was any air attack made upon France by the Germans. The French Government requested us to abstain from air attack on Germany, stating that it would provoke retaliation upon their war factories, which were unprotected. We contented ourselves with dropping pamphlets to rouse the Germans to a higher morality. This strange phase of the war on land and in the air astounded everyone. France and Britain remained impassive while Poland was in a few weeks destroyed or subjugated by the whole might of the German war machine. Hitler had no reason to complain of this.

The war at sea, on the contrary, began from the first hour with full intensity, and the Admiralty therefore became the active centre of events. On September 3 all our ships were sailing about the world on their normal business. Suddenly they were set upon by U-boats carefully posted beforehand, especially in the Western Approaches. At 9 p.m. that very night the outward-bound passenger liner Athenia, of 13,500 tons, was torpedoed, and foundered with a loss of 112 lives, including twenty-eight American citizens. This outrage broke upon the world within a few hours. The German Government, to prevent any misunderstanding in the United States, immediately issued a statement that I personally had ordered a bomb to be placed on board this vessel in order by its destruction to prejudice German-American relations. This falsehood received some credence in unfriendly quarters. On the 5th and 6th the Bosnia, Royal Sceptre, and Rio Claro were sunk off the coast of Spain. All these were important vessels.

Comprehensive plans existed at the Admiralty for multiplying our anti-submarine craft, and a war-time building programme of destroyers, both large and small, and of cruisers, with many ancillary vessels, was also ready in every detail, and came into operation automatically with the declaration of war. The previous conflict had proved the sovereign merits of convoy, and we adopted it in the North Atlantic forthwith. Before the end of the month regular ocean convoys were in operation, outward from the Thames and Liverpool and homeward from Halifax, Gibraltar, and Freetown. Upon all the vital need of feeding the Island and developing our power to wage war there now at once fell the numbing loss of the Southern Irish ports. This imposed a grievous restriction on the radius of action of our already scarce destroyers.

After the institution of the convoy system the next vital naval need was a safe base for the Fleet. In a war with Germany Scapa Flow is the true strategic point from which the British Navy can control the exits from the North Sea and enforce blockade and I felt it my duty to visit Scapa at the earliest moment. I therefore obtained leave from our daily Cabinets, and started for Wick with a small personal staff on the night of September 14. I spent most of the next two days inspecting the harbour and the entrances, with their booms and nets. I was assured that they were as good as in the last war, and that important additions and improvements were being made or were on the way. I stayed with Sir Charles Forbes, the Commander-in-Chief, in his flagship, Nelson, and discussed not only Scapa but the whole naval problem with him and his principal officers. The rest of the Fleet was hiding in Loch Ewe, and on the 17th the Admiral took me to them in the Nelson. The narrow entry into the loch was closed by several lines of indicator nets, and patrolling craft with Asdics and depth-charges, as well as picket-boats, were numerous and busy. On every side rose the purple hills of Scotland in all their splendour. My thoughts went back a quarter of a century to that other September when I had last visited Sir John Jellicoe and his captains in this very bay, and had found them with their long lines of battleships and cruisers drawn out at anchor, a prey to the same uncertainties as now afflicted us. Most of the captains and admirals of those days were dead, or had long passed into retirement. The responsible senior officers who were now presented to me as I visited the various ships had been young lieutenants or even midshipmen in those far-off days. Before the former war I had had three years’ preparation in which to make the acquaintance and approve the appointments of most of the high personnel, but now all these were new figures and new faces. The perfect discipline, style, and bearing, the ceremonial routine—all were unchanged. But an entirely different generation filled the uniforms and the posts. Only the ships had most of them been laid down in my tenure. None of them was new. It was a strange experience, like suddenly resuming a previous incarnation. It seemed that I was all that survived in the same position I had held so long ago. But no; the dangers had survived too. Danger from beneath the waves, more serious with more powerful U-boats; danger from the air, not merely of being spotted in your hiding-place, but of heavy and perhaps destructive attack!

No one had ever been over the same terrible course twice with such an interval between. No one had felt its dangers and responsibilities from the summit as I had, or, to descend to a small point, understood how First Lords of the Admiralty are treated when great ships are sunk and things go wrong. If we were in fact going over the same cycle a second time, should I have once again to endure the pangs of dismissal? Fisher, Wilson, Battenburg, Jellicoe, Beatty, Pakenham, Sturdee, all gone!

I feel like one

Who treads alone

Some banquet-hall deserted,

Whose lights are fled,

Whose garlands dead,

And all but he departed.

And what of the supreme, measureless ordeal in which we were again irrevocably plunged? Poland in its agony; France but a pale reflection of her former warlike ardour; the Russian Colossus no longer an ally, not even neutral, possibly to become a foe. Italy no friend. Japan no ally. Would America ever come in again? The British Empire remained intact and gloriously united, but ill-prepared, unready. We still had command of the sea. We were woefully outmatched in numbers in this new mortal weapon of the air. Somehow the light faded out of the landscape.

We joined our train at Inverness and travelled through the afternoon and night to London. As we got out at Euston the next morning I was surprised to see the First Sea Lord on the platform. Admiral Pound’s look was grave. “I have bad news for you, First Lord. The Courageous was sunk yesterday evening in the Bristol Channel.” The Courageous was one of our oldest aircraft-carriers, but a very necessary ship at this time. I thanked him for coming to break it to me himself, and said, “We can’t expect to carry on a war like this without that sort of thing happening from time to time. I have seen lots of it before.” And so to bath and the toil of another day.

By the end of September we had little cause for dissatisfaction with the results of the first impact of the war at sea. I could feel that I had effectively taken over the great department which I knew so well and loved with a discriminating eye. I now knew what there was in hand and on the way. I knew where everything was. I had visited all the principal naval ports and met all the Commanders-in-Chief. By the Letters Patent constituting the Board, the First Lord is “responsible to Crown and Parliament for all the business of the Admiralty”, and I certainly felt prepared to discharge that duty in fact as well as in form.

We had made the immense, delicate, and hazardous transition from peace to war. Forfeits had to be paid in the first few weeks by a worldwide commerce suddenly attacked contrary to formal international agreement by indiscriminate U-boat warfare; but the convoy system was now in full flow, and merchant ships were leaving our ports every day by scores with a gun and a nucleus of trained gunners. The Asdic-equipped trawlers and other small craft armed with depth-charges, all well prepared by the Admiralty before the outbreak, were now coming into commission in a growing stream. We all felt sure that the first attack of the U-boat on British trade had been broken and that the menace was in thorough and hardening control. It was obvious that the Germans would build submarines by hundreds, and no doubt numerous shoals were upon the slips in various stages of completion. In twelve months, certainly in eighteen, we must expect the main U-boat war to begin. But by that time we hoped that our mass of new flotillas and anti-U-boat craft, which was our First Priority, would be ready to meet it with a proportionate and effective predominance.

Meanwhile the transport of the Expeditionary Force to France was proceeding smoothly, and the blockade of Germany was being enforced by similar methods to those employed in the previous war. Overseas our cruisers were hunting down German ships, while at the same time providing cover against attack on our shipping by raiders. German shipping had come to a standstill and 325 German ships, totalling nearly 750,000 tons, were immobilised in foreign ports. Our Allies also played their part. The French took an important share in the control of the Mediterranean. In home waters and the Bay of Biscay they helped in the battle against the U-boats, and in the central Atlantic a powerful force based on Dakar formed part of the Allied plans against surface raiders.

In this same month I was delighted to receive a personal letter from President Roosevelt. I had only met him once in the previous war. It was at a dinner at Gray’s Inn, and I had been struck by his magnificent presence in all his youth and strength. There had been no opportunity for anything but salutations. “It is because you and I,” he wrote on the 11th, “occupied similar positions in the World War that I want you to know how glad I am that you are back again in the Admiralty. Your problems are, I realise, complicated by new factors, but the essential is not very different. What I want you and the Prime Minister to know is that I shall at all times welcome it if you will keep me in touch personally with anything you want me to know about. You can always send sealed letters through your pouch or my pouch.”

I responded with alacrity, using the signature of “Naval Person”, and thus began that long and memorable correspondence—covering nearly a thousand communications on each side, and lasting till his death more than five years later.

In October there burst upon us suddenly an event which touched the Admiralty in a most sensitive spot.

A report that a U-boat was inside Scapa Flow had driven the Grand Fleet to sea on the night of October 17, 1914. The alarm was premature. Now, after exactly a quarter of a century almost to a day, it came true. At 1.30 a.m. on October 14, 1939, a German U-boat braved the tides and currents, penetrated our defences, and sank the battleship Royal Oak as she lay at anchor. At first, out of a salvo of torpedoes, only one hit the bow, and caused a muffled explosion. So incredible was it to the Admiral and captain on board that a torpedo could have struck them, safe in Scapa Flow, that they attributed the explosion to some internal cause. Twenty minutes passed before the U-boat, for such she was, had reloaded her tubes and fired a second salvo. Then three or four torpedoes, striking in quick succession, ripped the bottom out of the ship. In ten minutes she capsized and sank. Most of the men were at action stations, but the rate at which the ship turned over made it almost impossible for anyone below to escape.

This episode, which must be regarded as a feat of arms on the part of the German U-boat commander, Captain Prien, gave a shock to public opinion. It might well have been politically fatal to any Minister who had been responsible for the pre-war precautions. Being a newcomer I was immune from such reproaches in these early months, and moreover, the Opposition did not attempt to make capital out of the misfortune. I promised the strictest inquiry. The event showed how necessary it was to perfect the defences of Scapa against all forms of attack before allowing it to be used. It was nearly six months before we were able to enjoy its commanding advantages.

Presently a new and formidable danger threatened our life. During September and October nearly a dozen merchant ships were sunk at the entrance of our harbours, although these had been properly swept for mines. The Admiralty at once suspected that a magnetic mine had been used. This was no novelty to us; we had even begun to use it on a small scale at the end of the previous war, but the terrible damage that could be done by large ground-mines laid in considerable depth by ships or aircraft had not been fully realised. Without a specimen of the mine it was impossible to devise the remedy. Losses by mines, largely Allied and neutral, in September and October had amounted to 56,000 tons, and in November Hitler was encouraged to hint darkly at his new “secret weapon” to which there was no counter. One night when I was at Chartwell Admiral Pound came down to see me in serious anxiety. Six ships had been sunk in the approaches to the Thames. Every day hundreds of ships went in and out of British harbours, and our survival depended on their movement. Hitler’s experts may well have told him that this form of attack would compass our ruin. Luckily he began on a small scale, and with limited stocks and manufacturing capacity.

Fortune also favoured us more directly. On November 22 between 9 and 10 p.m. a German aircraft was observed to drop a large object attached to a parachute into the sea near Shoeburyness. The coast here is girdled with great areas of mud which uncover with the tide, and it was immediately obvious that whatever the object was it could be examined and possibly recovered at low water. Here was our golden opportunity. Before midnight that same night two highly-skilled officers, Lt.-Commanders Ouvry and Lewis, from H.M.S. Vernon, the naval establishment responsible for developing underwater weapons, were called to the Admiralty, where the First Sea Lord and I interviewed them and heard their plans. By 1.30 in the morning they were on their way by car to Southend to undertake the hazardous task of recovery. Before daylight on the 23rd, in pitch-darkness, aided only by a signal lamp, they found the mine some 500 yards below high-water mark, but as the tide was then rising they could only inspect it and make their preparations for attacking it after the next high water.

The critical operation began early in the afternoon, by which time it had been discovered that a second mine was also on the mud near the first. Ouvry with Chief Petty Officer Baldwin tackled the first, whilst their colleagues, Lewis and Able Seaman Vearncombe, waited at a safe distance in case of accidents. After each prearranged operation Ouvry would signal to Lewis, so that the knowledge gained would be available when the second mine came to be dismantled. Eventually the combined efforts of all four men were required on the first, and their skill and devotion were amply rewarded. That evening some of the party came to the Admiralty to report that the mine had been recovered intact and was on its way to Portsmouth for detailed examination. I received them with enthusiasm. I gathered together eighty or a hundred officers and officials in our largest room, and a thrilled audience listened to the tale, deeply conscious of all that was at stake.

The whole power and science of the Navy were now applied; and it was not long before trial and experiment began to yield practical results. We worked all ways at once, devising first active means of attacking the mine by new methods of minesweeping and fuze-provocation, and, secondly, passive means of defence for all ships against possible mines in unswept, or ineffectually swept, channels. For this second purpose a most effective system of demagnetising ships by girdling them with an electric cable was developed. This was called “degaussing”, and was at once applied to ships of all types. But serious casualties continued. The new cruiser Belfast was mined in the Firth of Forth on November 21, and on December 4 the battleship Nelson was mined whilst entering Loch Ewe. Both ships were however able to reach a dockyard port. It is remarkable that German Intelligence failed to pierce our security measures covering the injury to the Nelson until the ship had been repaired and was again in service. Yet from the first many thousands in England had to know the true facts.

7 + s.w.w.

Experience soon gave us new and simpler methods of degaussing. The moral effect of its success was tremendous, but it was on the faithful, courageous, and persistent work of the mine-sweepers and the patient skill of the technical experts, who devised and provided the equipment they used, that we relied chiefly to defeat the enemy’s efforts. From this time onward, despite many anxious periods, the mine menace was always under control, and eventually the danger began to recede.

It is well to ponder this side of the naval war. In the event a significant proportion of our whole war effort had to be devoted to combating the mine. A vast output of material and money was diverted from other tasks, and many thousands of men risked their lives night and day in the minesweepers alone. The peak figure was reached in June 1944, when nearly sixty thousand were thus employed. Nothing daunted the ardour of the Merchant Navy, and their spirits rose with the deadly complications of the mining attack and our effective measures for countering it. Their toils and tireless courage were our salvation. In the wider sphere of naval operations no definite challenge had yet been made to our position. This was still to come, and a description of two major conflicts with German surface raiders may conclude my account of the war at sea in the year 1939.

Our long, tenuous blockade-line north of the Orkneys, largely composed of armed merchant-cruisers with supporting warships at intervals, was of course always liable to a sudden attack by German capital ships, and particularly by their two fast and most powerful battle-cruisers, the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau. We could not prevent such a stroke being made. Our hope was to bring the intruders to decisive action.

Late in the afternoon of November 23 the armed merchant-cruiser Rawalpindi, on patrol between Iceland and the Faroes, sighted an enemy warship which closed her rapidly. She believed the stranger to be the pocket-battleship Deutschland, and reported accordingly. Her commanding officer, Captain Kennedy, could have had no illusions about the outcome of such an encounter. His ship was but a converted passenger liner with a broadside of four old 6-inch guns, and his presumed antagonist mounted six 11-inch guns, besides a powerful secondary armament. Nevertheless he accepted the odds, determined to fight his ship to the last. The enemy opened fire at 10,000 yards, and the Rawalpindi struck back. Such a one-sided action could not last long, but the fight continued until, with all her guns out of action, the Rawalpindi was reduced to a blazing wreck. She sank some time after dark, with the loss of her captain and 270 of her gallant crew.

In fact it was not the Deutschland but the two battle-cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau which were engaged. These ships had left Germany two days before to attack our Atlantic convoys, but having encountered and sunk the Rawalpindi, and fearing the consequences of the exposure, they abandoned the rest of their mission and returned at once to Germany. The Rawalpindi’s heroic fight was not therefore in vain. The cruiser Newcastle, near by on patrol, saw the gun-flashes, and responded at once to the Rawalpindi’s first report, arriving on the scene with the cruiser Delhi to find the burning ship still afloat. She pursued the enemy, and at 6.15 p.m. sighted two ships in gathering darkness and heavy rain. One of these she recognised as a battle-cruiser, but lost contact in the gloom, and the enemy made good his escape.

The hope of bringing these two vital German ships to battle dominated all concerned, and the Commander-in-Chief put to sea at once with his whole fleet. By the 25th fourteen British cruisers were combing the North Sea, with destroyers and submarines co-operating and with the battle-fleet in support. But fortune was adverse; nothing was found, nor was there any indication of an enemy move to the west. Despite very severe weather the arduous search was maintained for seven days, and we eventually learnt that the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau had safely re-entered the Baltic. It is now known that they passed through our cruiser line patrolling near the Norwegian coast on the morning of November 26. The weather was thick and neither saw the other. Modern radar would have ensured contact, but then it was not available. Public impressions were unfavourable to the Admiralty. We could not bring home to the outside world the vastness of the seas or the intense exertions which the Navy was making in so many areas. After more than two months of war and several serious losses we had nothing to show on the other side. Nor could we yet answer the question, “What is the Navy doing?”

The attack on our ocean commerce by surface raiders would have been even more formidable could it have been sustained. The three German pocket-battleships permitted by the Treaty of Versailles had been designed with profound thought as commerce-destroyers. Their six 11-inch guns, their 26-knot speed, and the armour they carried had been compressed with masterly skill into the limits of a 10,000-ton displacement. No single British cruiser could match them. The German 8-inch-gun cruisers were more modern than ours, and if employed as commerce-raiders would also be a formidable threat. Besides this the enemy might use disguised heavily-armed merchantmen. We had vivid memories of the depredations of the Emden and Koenigsberg in 1914, and of the thirty or more warships and armed merchantmen they had forced us to combine for their destruction.

There were rumours and reports before the outbreak of the new war that one or more pocket-battleships had already sailed from Germany. The Home Fleet searched but found nothing. We now know that both the Deutschland and the Graf Spee sailed from Germany between August 21 and 24, and were already through the danger zone and loose in the oceans before our blockade and northern patrols were organised. On September 3 the Deutschland, having passed through the Denmark Strait, was lurking near Greenland. The Graf Spee had crossed the North Atlantic trade route unseen and was already far south of the Azores. Each was accompanied by an auxiliary vessel to replenish fuel and stores. Both at first remained inactive and lost in the ocean spaces. Unless they struck they won no prizes. Until they struck they were in no danger.

On September 30 the British liner Clement, of 5,000 tons, sailing independently, was sunk by the Graf Spee off Pernambuco. The news electrified the Admiralty. It was the signal for which we had been waiting. A number of hunting groups were immediately formed, comprising all our available aircraft-carriers, supported by battleships, battle-cruisers, and cruisers. Each group of two or more ships was judged to be capable of catching and destroying a pocket-battleship.

In all, during the ensuing months the search for two raiders entailed the formation of nine hunting groups, comprising twenty-three powerful ships. Working from widely-dispersed bases in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, these groups could cover the main focal areas traversed by our shipping. To attack our trade the enemy must place himself within reach of at least one of them.

The Deutschland, which was to have harassed our lifeline across the North-west Atlantic, interpreted her orders with comprehending caution. At no time during her two and a half months’ cruise did she approach a convoy. Her determined efforts to avoid British forces prevented her from making more than two kills, one being a small Norwegian ship. Early in November she slunk back to Germany, passing again through Arctic waters. The mere presence of this powerful ship upon our main trade route had however imposed, as was intended, a serious strain upon our escorts and hunting groups in the North Atlantic. We should in fact have preferred her activity to the vague menace she embodied.

The Graf Spee was more daring and imaginative, and soon became the centre of attention in the South Atlantic. Her practice was to make a brief appearance at some point, claim a victim, and vanish again into the trackless ocean wastes. After a second appearance farther south on the Cape route, in which she sank only one ship, there was no further sign of her for nearly a month, during which our hunting groups were searching far and wide in all areas, and special vigilance was enjoined in the Indian Ocean. This was in fact her destination, and on November 15 she sank a small British tanker in the Mozambique Channel, between Madagascar and the mainland. Having thus registered her appearance as a feint in the Indian Ocean, in order to draw the hunt in that direction, her captain—Langsdorff, a high-class person—promptly doubled back and, keeping well south of the Cape, re-entered the Atlantic. This move had not been unforeseen; but our plans to intercept him were foiled by the quickness of his withdrawal. It was by no means clear to the Admiralty whether in fact one raider was on the prowl or two, and exertions were made both in the Indian and Atlantic Oceans. We also thought that the Spee was her sister ship, the Scheer. The disproportion between the strength of the enemy and the counter-measures forced upon us was vexatious. It recalled to me the anxious weeks before the action at Coronel and later at the Falkland Islands in December 1914, when we had to be prepared at seven or eight different points, in the Pacific and South Atlantic, for the arrival of Admiral von Spee with the earlier edition of the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. A quarter of a century had passed, but the puzzle was the same. It was with a definite sense of relief that we learnt that the Spee had appeared once more on the Cape-Freetown route, sinking the Doric Star and another ship on December 2 and one more on the 7th.

From the beginning of the war Commodore Harwood’s special care and duty had been to cover British shipping off the River Plate and Rio de Janeiro. He was convinced that sooner or later the Spee would come towards the Plate, where the richest prizes were offered to her. He had carefully thought out the tactics which he would adopt in an encounter. Together, his 8-inch cruisers Cumberland and Exeter, and his 6-inch cruisers Ajax and Achilles, the latter being a New Zealand ship manned mainly by New Zealanders, could not only catch but kill. However, the needs of fuel and refit made it unlikely that all four would be present “on the day”. If they were not the issue was disputable. On hearing that the Doric Star had been sunk on December 2, Harwood guessed right. Although she was over 3,000 miles away he assumed that the Spee would come towards the Plate. He estimated with luck and wisdom that she might arrive by the 13th. He ordered all his available forces to concentrate there by December 12. Alas, the Cumberland was refitting at the Falklands; but on the morning of the 13th Exeter, Ajax, and Achilles were in company at the centre of the shipping routes off the mouth of the river. Sure enough, at 6.14 a.m. smoke was sighted to the east. The longed-for collision had come.

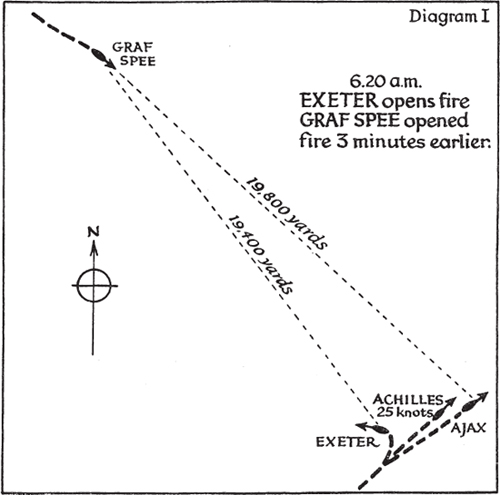

Harwood, in the Ajax, disposing his forces so as to attack the pocket-battleship from widely-divergent quarters and thus confuse her fire, advanced at the utmost speed of his small squadron. Captain Langsdorff thought at first glance that he had only to deal with one light cruiser and two destroyers, and he too went full speed ahead; but a few moments later he recognised the quality of his opponents, and knew that a mortal action impended. The two forces were now closing at nearly fifty miles an hour. Langsdorff had but a minute to make up his mind. His right course would have been to turn away immediately so as to keep his assailants as long as possible under the superior range and weight of his 11-inch guns, to which the British could not at first have replied. He would thus have gained for his undisturbed firing the difference between adding speeds and subtracting them. He might well have crippled one of his foes before any could fire at him. He decided, on the contrary, to hold on his course and make for the Exeter. The action therefore began almost simultaneously on both sides.

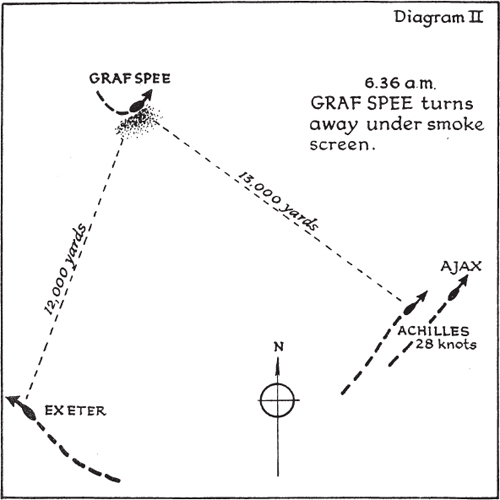

Commodore Harwood’s tactics proved advantageous. The 8-inch salvoes from the Exeter struck the Spee from the earliest stages of the fight. Meanwhile the 6-inch cruisers were also hitting hard and effectively. Soon the Exeter received a hit which, besides knocking out B turret, destroyed all the communications on the bridge, killed or wounded nearly all upon it, and put the ship temporarily out of control. By this time however the 6-inch cruisers could no longer be neglected by the enemy, and the Spee shifted her main armament to them, thus giving respite to the Exeter at a critical moment. The German battleship, plastered from three directions, found the British attack too hot, and soon afterwards turned away under a smoke-screen with the apparent intention of making for the River Plate. Langsdorff had better have done this earlier.

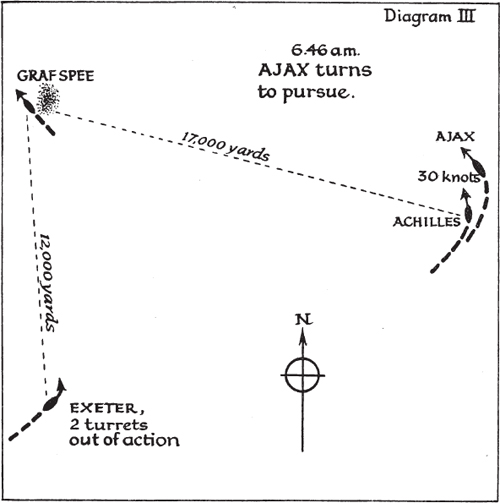

After this turn the Spee once more engaged the Exeter, hard hit by the 11-inch shells. All her forward guns were out of action. She was burning fiercely amidships and had a heavy list. Captain Bell, unscathed by the explosion on the bridge, gathered two or three officers round him in the after control-station, and kept his ship in action with her sole remaining turret, until at 7.30 failure of pressure put this too out of action. He could do no more. At 7.40 the Exeter turned away to effect repairs and took no further part in the fight.

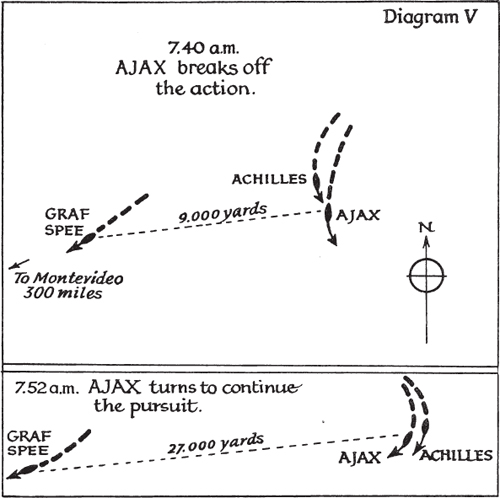

9*

The Ajax and Achilles, already in pursuit, continued the action in the most spirited manner. The Spee turned all her heavy guns upon them. By 7.25 the two after-turrets in the Ajax had been knocked out, and the Achilles had also suffered damage. These two light cruisers were no match for the enemy in gun-power, and, finding that his ammunition was running low, Harwood in the Ajax decided to break off the fight till dark, when he would have better chances of using his lighter armament effectively, and perhaps his torpedoes. He therefore turned away under cover of smoke, and the enemy did not follow. This fierce action had lasted an hour and twenty minutes. During all the rest of the day the Spee made for Montevideo, the British cruisers hanging grimly on her heels, with only occasional interchanges of fire. Shortly after midnight the Spee entered Montevideo, and lay there repairing damage, taking in stores, landing wounded, transhipping personnel to a German merchant ship, and reporting to the Fuehrer. Ajax and Achilles lay outside, determined to dog her to her doom should she venture forth. Meanwhile on the night of the 14th the Cumberland, which had been steaming at full speed from the Falklands, took the place of the utterly crippled Exeter. The arrival of this 8-inch-gun cruiser restored to its narrow balance a doubtful situation.

On December 16 Captain Langsdorff telegraphed to the German Admiralty that escape was hopeless. “Request decision on whether the ship should be scuttled in spite of insufficient depth in the estuary of the Plate, or whether internment is to be preferred.”

At a conference presided over by Hitler, at which Raeder and Jodl were present, the following answer was decided on:

“Attempt by all means to extend the time in neutral waters.… Fight your way through to Buenos Aires if possible. No internment in Uruguay. Attempt effective destruction if ship is scuttled.”

Accordingly during the afternoon of the 17th the Spee transferred more than seven hundred men, with baggage and provisions, to the German merchant ship in the harbour. Shortly afterwards Admiral Harwood learnt that she was weighing anchor. At 6.15 p.m., watched by immense crowds, she left harbour and steamed slowly seawards, awaited hungrily by the British cruisers. At 8.54 p.m., as the sun sank, the Ajax’s aircraft reported: “Graf Spee has blown herself up.” Langsdorff was broken-hearted by the loss of his ship and shot himself two days later.

Thus ended the first surface challenge to British trade on the oceans. No other raider appeared until the spring of 1940, when a new campaign opened, utilising disguised merchant ships. These could more easily avoid detection, but on the other hand could be mastered by lesser forces than those required to destroy a pocket-battleship.