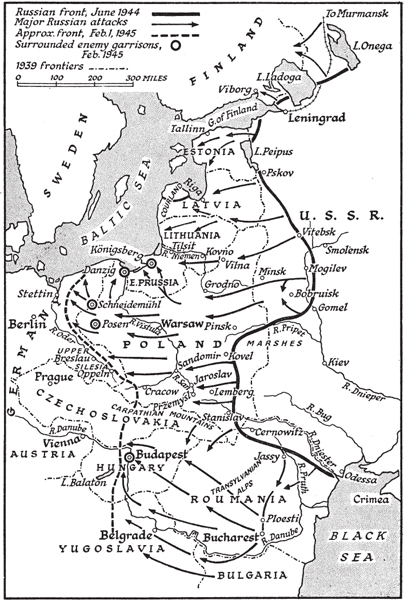

THE reader must now hark back to the Russian struggle, which in scale far exceeded the operations with which my account has hitherto been concerned, and formed of course the foundation upon which the British and American Armies had approached the climax of the war. The Russians had given their enemy little time to recover from their severe reverses of the early winter of 1943. In mid-January 1944 they attacked on a 120-mile front from Lake limen to Leningrad and pierced the defences before the city. Farther south by the end of February the Germans had been driven back to the shores of Lake Peipus. Leningrad was freed once and for all, and the Russians stood on the borders of the Baltic States. Further onslaughts to the west of Kiev forced the Germans back towards the old Polish frontier. The whole southern front was aflame and the German line deeply penetrated at many points. One great pocket of surrounded Germans was left behind at Kersun, from which few escaped. Throughout March the Russians pressed their advantage all along the line and in the air. From Gomel to the Black Sea the invaders were in full retreat, which did not end until they had been thrust across the Dniester, back into Roumania and Poland. Then the spring thaw brought them a short respite. In the Crimea however operations were still possible, and in April the Russians set about destroying the Seventeenth German Army and regaining Sebastopol.

The magnitude of these victories raised issues of far-reaching importance. The Red Army now loomed over Central and Eastern Europe. What was to happen to Poland, Hungary, Roumania, Bulgaria, and above all, to Greece, for whom we had tried so hard and sacrificed so much? Would Turkey come in on our side? Would Yugoslavia be engulfed in the Russian flood? Post-war Europe seemed to be taking shape and some political arrangement with the Soviets was becoming urgent.

On May 18 the Soviet Ambassador in London had called at the Foreign Office to discuss a general suggestion which Mr. Eden had made that the U.S.S.R. should temporarily regard Roumanian affairs as mainly their concern under war conditions while leaving Greece to us. The Russians were prepared to accept this, but wished to know if we had consulted the United States. If so they would agree. On the 31st I accordingly sent a personal telegram to Mr. Roosevelt:

… I hope you may feel able to give this proposal your blessing. We do not of course wish to carve up the Balkans into spheres of influence, and in agreeing to the arrangement we should make it clear that it applied only to war conditions and did not affect the rights and responsibilities which each of the three Great Powers will have to exercise at the peace settlement and afterwards in regard to the whole of Europe. The arrangement would of course involve no change in the present collaboration between you and us in the formulation and execution of Allied policy towards these countries. We feel however that the arrangement now proposed would be a useful device for preventing any divergence of policy between ourselves and them in the Balkans.

The first reactions of the State Department were cool. Mr. Hull was nervous of any suggestion that “might appear to savour of the creation or acceptance of the idea of spheres of influence”, and on June n the President cabled:

… Briefly, we acknowledge that the military responsible Government in any given territory will inevitably make decisions required by military developments, but are convinced that the natural tendency for such decisions to extend to other than military fields would be strengthened by an agreement of the type suggested. In our opinion, this would certainly result in the persistence of differences between you and the Soviets and in the division of the Balkan region into spheres of influence despite the declared intention to limit the arrangment to military matters.

We believe efforts should preferably be made to establish consultative machinery to dispel misunderstandings and restrain the tendency toward the development of exclusive spheres.

I was much concerned at this message and replied on the same day:

… Action is paralysed if everybody is to consult everybody else about everything before it is taken. Events will always outstrip the changing situations in these Balkan regions. Somebody must have the power to plan and act. A Consultative Committee would be a mere obstruction, always overridden in any case of emergency by direct interchanges between you and me, or either of us and Stalin.

See, now, what happened at Easter. We were able to cope with this mutiny of the Greek forces entirely in accordance with your own views. This was because I was able to give constant orders to the military commanders, who at the beginning advocated conciliation, and above all no use or even threat of force. Very little life was lost. The Greek situation has been immensely improved, and, if firmness is maintained, will be rescued from confusion and disaster. The Russians are ready to let us take the lead in the Greek business, which means that E.A.M.* and all its malice can be controlled by the national forces of Greece.… If in these difficulties we had had to consult other Powers and a set of triangular or quadrangular telegrams got started the only result would have been chaos or impotence.

It seems to me, considering the Russians are about to invade Roumania in great force and are going to help Roumania recapture part of Transylvania from Hungary, provided the Roumanians play, which they may, considering all that, it would be a good thing to follow the Soviet leadership, considering that neither you nor we have any troops there at all and that they will probably do what they like anyhow.… To sum up, I propose that we agree that the arrangements I set forth in my message of May 31 may have a trial of three months, after which it must be reviewed by the three Powers.

On June 13 the President agreed to this proposal, but added: “We must be careful to make it clear that we are not establishing any postwar spheres of influence.” I shared his view, and replied the next day:

I am deeply grateful to you for your telegram. I have asked the Foreign Secretary to convey the information to Molotov and to make it clear that the reason for the three months’ limit is in order that we should not prejudge the question of establishing post-war spheres of influence.

I reported the situation to the War Cabinet that afternoon, and it was agreed that, subject to the time-limit of three months, the Foreign Secretary should inform the Soviet Government that we accepted this general division of responsibility. This was done on June 19. The President however was not happy about the way we had acted, and I received a pained message saying “we were disturbed that your people took this matter up with us only after it had been put up to the Russians.” On June 23 accordingly I outlined to the President, in reply to his rebuke, the situation as I saw it from London:

The Russians are the only Power that can do anything in Roumania.… On the other hand, the Greek burden rests almost entirely upon us, and has done so since we lost 40,000 men in a vain endeavour to help them in 1941. Similarly, you have let us play the hand in Turkey, but we have always consulted you on policy, and I think we have been agreed on the line to be followed. It would be quite easy for me, on the general principle of slithering to the Left, which is so popular in foreign policy, to let things rip, when the King of Greece would probably be forced to abdicate and E.A.M. would work a reign of terror in Greece, forcing the villagers and many other classes to form Security Battalions under German auspices to prevent utter anarchy. The, only way I can prevent this is by persuading the Russians to quit boosting E.A.M. and ramming it forward with all their force. Therefore I proposed to the Russians a temporary working arrangement for the better conduct of the war. This was only a proposal, and had to be referred to you for your agreement.

I have also taken action to try to bring together a union of the Tito forces with those in Serbia, and with all adhering to the Royal Yugoslav Government, which we have both recognised. You have been informed at every stage of how we are bearing this heavy burden, which at present rests mainly on us. Here again nothing would be easier than to throw the King and the Royal Yugoslav Government to the wolves and let a civil war break out in Yugoslavia, to the joy of the Germans. I am struggling to bring order out of chaos in both cases and concentrate all efforts against the common foe. I am keeping you constantly informed, and I hope to have your confidence and help within the spheres of action in which initiative is assigned to us.

Mr. Roosevelt’s reply settled this argument between friends. “It appears,” he cabled, “that both of us have inadvertently taken unilateral action in a direction that we both now agree to have been expedient for the time being. It is essential that we should always be in agreement in matters bearing on our Allied war effort.”

“You may be sure,” I replied, “I shall always be looking to our agreement in all matters before, during, and after.”

The difficulties however continued on a Governmental level. Stalin, as soon as he realised the Americans had doubts, insisted on consulting them direct, and in the end we were unable to reach any final agreement about dividing responsibilities in the Balkan peninsula. Early in August the Russians dispatched from Italy by a subterfuge a mission to E.L.A.S., the military component of E.A.M., in Northern Greece. In the light of American official reluctance and of this instance of Soviet bad faith, we abandoned our efforts to reach a major understanding until I met Stalin in Moscow two months later. By then much had happened on the Eastern Front.

In Finland, Russian troops, very different in quality and armament from those who had fought there in 1940, broke through the Mannerheim Line, reopened the railway from Leningrad to Murmansk, the terminal of our Arctic convoys, and by the end of August compelled the Finns to sue for an armistice. Their main attack on the German front began on June 23. Many towns and villages had been turned into strong positions, with all-round defence, but they were successively surrounded and disposed of, while the Red armies poured through the gaps between. At the end of July they had reached the Niemen at Kovno and Grodno. Here, after an advance of 250 miles in five weeks, they were brought to a temporary halt to replenish. The German losses had been crushing. Twenty-five divisions had ceased to exist, and an equal number were cut off in Courland.* On July 17 alone 57,000 German prisoners were marched through Moscow—who knows whither?

To the southward of these victories lay Roumania. Till August was far advanced the German line from Cernowitz to the Black Sea barred the way to the Ploesti oilfields and the Balkans. It had been weakened by withdrawal of troops to sustain the sagging line farther north, and under violent attacks, beginning on August 22, it rapidly disintegrated. Aided by landings on the coast, the Russians made short work of the enemy. Sixteen German divisions were lost. On August 23 a coup d’état in Bucharest, organised by the young King Michael and his close advisers, led to a complete reversal of the whole military position. The Roumanian armies followed their King to a man. Within three days before the arrival of the Soviet troops the German forces had been disarmed or had retired over the northern frontiers. By September 1 Bucharest had been evacuated by the Germans. The Roumanian armies disintegrated and the country was overrun. The Roumanian Government capitulated. Bulgaria after a last-minute attempt to declare war on Germany, was overwhelmed. Wheeling to the west, the Russian armies drove up the valley of the Danube and through the Transylvanian Alps to the Hungarian border, while their left flank, south of the Danube, lined up on the frontier of Yugoslavia. Here they prepared for the great westerly drive which in due time was to carry them to Vienna.

In Poland there was a tragedy which requires a more detailed account.

By late July the Russian armies stood before the river Vistula, and all reports indicated that in the very near future Poland would be in Russian hands. The leaders of the Polish Underground Army, which owed allegiance to the London Government, had now to decide when to raise a general insurrection against the Germans, in order to speed the liberation of their country and prevent them fighting a series of bitter defensive actions on Polish territory, and particularly in Warsaw itself. The Polish commander, General Bor-Komorowski, and his civilian adviser were authorised by the Polish Government in London to proclaim a general insurrection whenever they deemed fit. The moment indeed seemed opportune. On July 20 came the news of the plot against Hitler, followed swiftly by the Allied break-out from the Normandy beach-head. About July 22 the Poles intercepted wireless messages from the German Fourth Panzer Army ordering a general withdrawal to the west of the Vistula. The Russians crossed the river on the same day, and their patrols pushed forward in the direction of Warsaw. There seemed little doubt that a general collapse was at hand.

27—s.w.w.

General Bor therefore decided to stage a major rising and liberate the city. He had about forty thousand men, with reserves of food and ammunition for seven to ten days’ fighting. The sound of Russian guns across the Vistula could now be heard. The Soviet Air Force began bombing the Germans in Warsaw from recently captured airfields near the capital, of which the closest was only twenty minutes’ flight away. At the same time a Communist Committee of National Liberation had been formed in Eastern Poland, and the Russians announced that liberated territory would be placed under their control. Soviet broadcasting stations had for a considerable time been urging the Polish population to drop all caution and start a general revolt against the Germans. On July 29, three days before the rising began, the Moscow radio station broadcast an appeal from the Polish Communists to the people of Warsaw, saying that the guns of liberation were now within hearing, and calling upon them as in 1939 to join battle with the Germans, this time for decisive action. “For Warsaw, which did not yield but fought on, the hour of action has already arrived.” After pointing out that the German plan to set up defence points would result in the gradual destruction of the city, the broadcast ended by reminding the inhabitants that “all is lost that is not saved by active effort”, and that “by direct active struggle in the streets, houses, etc., of Warsaw the moment of final liberation will be hastened and the lives of our brethren saved”.

On the evening of July 31 the Underground command in Warsaw got news that Soviet tanks had broken into the German defences east of the city. The German military wireless announced, “To-day the Russians started a general attack on Warsaw from the south-east.” Russian troops were now at points less than ten miles away. In the capital itself the Polish Underground command ordered a general insurrection at 5 p.m. on the following day. General Bor has himself described what happened:

At exactly five o’clock thousands of windows flashed as they were flung open. From all sides a hail of bullets struck passing Germans, riddling their buildings and their marching formations. In the twinkling of an eye the remaining civilians disappeared from the streets. From the entrances of houses our men streamed out and rushed to the attack. In fifteen minutes an entire city of a million inhabitants was engulfed in the fight. Every kind of traffic ceased. As a big communications centre where roads from north, south, east, and west converged, in the immediate rear of the German front, Warsaw ceased to exist. The battle for the city was on.

The news reached London next day, and we anxiously waited for more. The Soviet radio was silent and Russian air activity ceased. On August 4 the Germans started to attack from strongpoints which they held throughout the city and suburbs. The Polish Government in London told us of the agonising urgency of sending in supplies by air. The insurgents were now opposed by five hastily concentrated German divisions. The Hermann Goering Division had also been brought from Italy, and two more S.S. divisions arrived soon afterwards.

I accordingly telegraphed to Stalin:

At urgent request of Polish Underground Army we are dropping, subject to weather, about sixty tons of equipment and ammunition into the south-west quarter of Warsaw, where it is said a Polish revolt against the Germans is in fierce struggle. They also say that they appeal for Russian aid, which seems to be very near. They are being attacked by one and a half German divisions. This may be of help to your operation.

The reply was prompt and grim.

I have received your message about Warsaw.

I think that the information which has been communicated to you by the Poles is greatly exaggerated and does not inspire confidence. One could reach that conclusion even from the fact that the Polish emigrants have already claimed for themselves that they all but captured Vilna with a few stray units of the Home Army, and even announced that on the radio. But that of course does not in any way correspond with the facts. The Home Army of the Poles consists of a few detachments, which they incorrectly call divisions. They have neither artillery nor aircraft nor tanks. I cannot imagine how such detachments can capture Warsaw, for the defence of which the Germans have produced four tank divisions, among them the Hermann Goering Division.

Meanwhile the battle went on street by street against the German “Tiger” tanks, and by August 9 the Germans had driven a wedge right across the city through to the Vistula, breaking up the Polish-held districts into isolated sectors. The gallant attempts of the R.A.F., with Polish, British, and Dominion crews, to fly to the aid of Warsaw from Italian bases were both forlorn and inadequate. Two planes appeared on the night of August 4, and three four nights later.

The Polish Prime Minister, Mikolajczyk, had been in Moscow since July 30 trying to establish some kind of terms with the Soviet Government, which had recognised the Polish Communist Committee of National Liberation, the Lublin Committee, as we called it, as the future administrators of the country. These negotiations were carried on throughout the early days of the Warsaw rising. Messages from General Bor were reaching Mikolajczyk daily, begging for ammunition and anti-tank weapons and for help from the Red Army. Meanwhile the Russians pressed for agreement upon the post-war frontiers of Poland and the setting up of a joint Government. A last fruitless talk took place with Stalin on August 9.

On the night of August 16 Vyshinsky asked the United States Ambassador in Moscow to call, and, explaining that he wished to avoid the possibility of misunderstanding, read out the following astonishing statement:

The Soviet Government cannot of course object to English or American aircraft dropping arms in the region of Warsaw, since this is an American and British affair. But they decidedly object to American or British aircraft, after dropping arms in the region of Warsaw, landing on Soviet territory, since the Soviet Government do not wish to associate themselves either directly or indirectly with the adventure in Warsaw.

On the same day I received the following message couched in softer terms from Stalin:

After the conversation with M. Mikolajczyk I gave orders that the command of the Red Army should drop arms intensively in the Warsaw sector. A parachutist liaison officer was also dropped, who, according to the report of the command, did not reach his objective as he was killed by the Germans.

Further, having familiarised myself more closely with the Warsaw affair, I am convinced that the Warsaw action represents a reckless and terrible adventure which is costing the population large sacrifices. This would not have been if the Soviet command had been informed before the beginning of the Warsaw action and if the Poles had maintained contact with it.

In the situation which has arisen the Soviet command has come to the conclusion that it must dissociate itself from the Warsaw adventure, as it cannot take either direct or indirect responsibility for the Warsaw action.

According to Mikolajczyk’s account, the first paragraph of this telegram is quite untrue. Two officers arrived safely in Warsaw and were received by the Polish command. A Soviet colonel had also been there for some days, and sent messages to Moscow via London urging support for the insurgents.

Four days later Roosevelt and I sent Stalin the following joint appeal, which the President had drafted:

We are thinking of world opinion if the anti-Nazis in Warsaw are in effect abandoned. We believe that all three of us should do the utmost to save as many of the patriots there as possible. We hope that you will drop immediate supplies and munitions to the patriot Poles in Warsaw, or will you agree to help our planes in doing it very quickly? We hope you will approve. The time element is of extreme importance.

This was the reply we got:

I have received the message from you and Mr. Roosevelt about Warsaw. I wish to express my opinions.

Sooner or later the truth about the group of criminals who have embarked on the Warsaw adventure in order to seize power will become known to everybody. These people have exploited the good faith of the inhabitants of Warsaw, throwing many almost unarmed people against the German guns, tanks and aircraft. A situation has arisen in which each new day serves, not the Poles for the liberation of Warsaw but the Hitlerites who are inhumanly shooting down the inhabitants of Warsaw.

From the military point of view, the situation which has arisen, by increasingly directing the attention of the Germans to Warsaw, is just as unprofitable for the Red Army as for the Poles. Meanwhile the Soviet troops, which have recently encountered new and notable efforts by the Germans to go over to the counter-attack, are doing everything possible to smash these counter-attacks of the Hitlerites and to go over to a new wide-scale attack in the region of Warsaw. There can be no doubt that the Red Army is not sparing its efforts to break the Germans round Warsaw and to free Warsaw for the Poles. That will be the best and most effective help for the Poles who are anti-Nazis.

Meanwhile the agony of Warsaw reached its height. “The German tank forces during last night” [August 11], cabled an eye-witness, “made determined efforts to relieve some of their strong-points in the city. This is no light task however, as on the corner of every street are built huge barricades, mostly constructed of concrete pavement slabs torn up from the streets especially for this purpose, hi most cases the attempts failed, so the tank crews vented their disappointment by setting fire to several houses and shelling others from a distance. In many cases they also set fire to the dead, who litter the streets in many places.…

“When the Germans were bringing supplies by tanks to one of their outposts they drove before them 500 women and children to prevent the [Polish] troops from taking action against them. Many of them were killed and wounded. The same kind of action has been reported from many other parts of the city.

“The dead are buried in backyards and squares. The food situation is continually deteriorating, but as yet there is no starvation. To-day [August 15] there is no water at all in the pipes. It is being drawn from the infrequent wells and house supplies. AU quarters of the town are under shell fire, and there are many fires. The dropping of supplies has intensified the morale. Everyone wants to fight and will fight, but the uncertainty of a speedy conclusion is depressing.…”

The battle also raged literally underground. The only means of communication between the different sectors held by the Poles lay through the sewers. The Germans threw hand grenades and gas bombs down the manholes. Battles developed in pitch-darkness between men waist-deep in excrement, fighting hand to hand at times with knives or drowning their opponents in the slime. Above ground German artillery and fighters set alight large areas of the city.

I had hoped that the Americans would support us in drastic action, but Mr. Roosevelt was adverse. On September 1 I received Miko-lajczyk on his return from Moscow. I had little comfort to offer. He told me that he was prepared to propose a political settlement with the Lublin Committee, offering them fourteen seats in a combined Government. These proposals were debated under fire by the representatives of the Polish Underground in Warsaw itself. The suggestion was accepted unanimously. Most of those who took part in these decisions were tried a year later for “treason” before a Soviet court in Moscow.

When the Cabinet met on the night of September 4 I thought the issue so important that though I had a touch of fever I went from my bed to our underground room. We had met together on many unpleasant affairs. I do not remember any occasion when such deep anger was shown by all our members, Tory, Labour, Liberal alike. I should have liked to say, “We are sending our aeroplanes to land in your territory, after delivering supplies to Warsaw. If you do not treat them properly all convoys will be stopped from this moment by us.” But the reader of these pages in after-years must realise that everyone always has to keep in mind the fortunes of millions of men fighting in a world-wide struggle, and that terrible and even humbling submissions must at times be made to the general aim. I did not therefore propose this drastic step. It might have been effective, because we were dealing with men in the Kremlin who were governed by calculation and not by emotion. They did not mean to let the spirit of Poland rise again at Warsaw. Their plans were based on the Lublin Committee. That was the only Poland they cared about. The cutting off of the convoys at this critical moment in their great advance would perhaps have bulked in their minds as much as considerations of honour, humanity, decent commonplace good faith, usually count with ordinary people. The War Cabinet in their collective capacity sent Stalin the following telegram. It was the best we thought it wise to do:

The War Cabinet wish the Soviet Government to know that public opinion in this country is deeply moved by the events in Warsaw and by the terrible sufferings of the Poles there. Whatever the rights and wrongs about the beginnings of the Warsaw rising, the people of Warsaw themselves cannot be held responsible for the decision taken. Our people cannot understand why no material help has been sent from outside to the Poles in Warsaw. The fact that such help could not be sent on account of your Government’s refusal to allow United States aircraft to land on aerodromes in Russian hands is now becoming publicly known. If on top of all this the Poles in Warsaw should now be overwhelmed by the Germans, as we are told they must be within two or three days, the shock to public opinion here will be incalculable.…

Out of regard for Marshal Stalin and for the Soviet peoples, with whom it is our earnest desire to work in future years, the War Cabinet have asked me to make this further appeal to the Soviet Government to give whatever help may be in their power, and above all to provide facilities for United States aircraft to land on your airfields for this purpose.

On September 10, after six weeks of Polish torment, the Kremlin appeared to change their tactics. That afternoon shells from the Soviet artillery began to fall upon the eastern outskirts of Warsaw, and Soviet planes appeared again over the city. Polish Communist forces, under Soviet orders, fought their way into the fringe of the capital. From September 14 onwards the Soviet Air Force dropped supplies; but few of the parachutes opened and many of the containers were smashed and useless. The following day the Russians occupied the Praga suburb, but went no farther. They wished to have the non-Communist Poles destroyed to the full, but also to keep alive the idea that they were going to their rescue. Meanwhile, house by house, the Germans proceeded with their liquidation of Polish centres of resistance throughout the city. A fearful fate befell the population. Many were deported by the Germans. General Bor’s appeals to the Soviet commander, Marshal Rokossovsky, were unanswered. Famine reigned.

My efforts to get American aid led to one isolated but large-scale operation. On September 18 a hundred and four heavy bombers flew over the capital, dropping supplies. It was too late. On the evening of October 2 Mikolajczyk came to tell me that the Polish forces in Warsaw were about to surrender to the Germans. One of the last broadcasts from the heroic city was picked up in London:

This is the stark truth. We were treated worse than Hitler’s satellites, worse than Italy, Roumania, Finland. May God, Who is just, pass judgment on the terrible injustice suffered by the Polish nation, and may He punish accordingly all those who are guilty.

Your heroes are the soldiers whose only weapons against tanks, planes, and guns were their revolvers and bottles filled with petrol. Your heroes are the women who tended the wounded and carried messages under fire, who cooked in bombed and ruined cellars to feed children and adults, and who soothed and comforted the dying. Your heroes are the children who went on quietly playing among the smouldering ruins. These are the people of Warsaw.

Immortal is the nation that can muster such universal heroism. For those who have died have conquered, and those who live on will fight on, will conquer and again bear witness that Poland lives when the Poles live.

These words are indelible. The struggle in Warsaw had lasted more than sixty days. Of the 40,000 men and women of the Polish Underground Army about 15,000 fell. Out of a population of a million nearly 200,000 had been stricken. The suppression of the revolt cost the German Army 10,000 killed, 7,000 missing, and 9,000 wounded. The proportions attest the hand-to-hand character of the fighting.

When the Russians entered the city three months later they found little but shattered streets and the unburied dead. Such was their liberation of Poland, where they now rule. But this cannot be the end of the story.