THE arrangements which I had made with the President in the summer to divide our responsibilities for looking after particular countries affected by the movements of the armies had tided us over the three months for which our agreement ran. But as the autumn drew on everything in Eastern Europe became more intense. I felt the need of another personal meeting with Stalin, whom I had not seen since Teheran, and with whom, in spite of the Warsaw tragedy, I felt new links since the successful opening of “Overlord”. The Russian armies were now pressing heavily upon the Balkan scene, and Roumania and Bulgaria were in their power. Belgrade was soon to fall and Hitler was fighting with desperate obstinacy to keep his grip on Hungary. As the victory of the Grand Alliance became only a matter of time it was natural that Russian ambitions should grow. Communism raised its head behind the thundering Russian battle-front. Russia was the Deliverer, and Communism the gospel she brought.

I had never felt that our relations with Roumania and Bulgaria in the past called for any special sacrifices from us. But the fate of Poland and Greece struck us keenly. For Poland we had entered the war; for Greece we had made painful efforts. Both their Governments had taken refuge in London, and we considered ourselves responsible for their restoration to their own country, if that was what their peoples really wished. In the main these feelings were shared by the United States, but they were very slow in realising the upsurge of Communist influence, which slid on before, as well as followed,’ the onward march of the mighty armies directed from the Kremlin. I hoped to take advantage of the better relations with the Soviets to reach satisfactory solutions of these new problems opening between East and West.

Besides these grave issues which affected the whole of Central Europe, the questions of World Organisation were also thrusting themselves upon all our minds. A lengthy conference had been held at Dumbarton Oaks, near Washington, between August and October, at which the United States, Great Britain, the U.S.S.R., and China had produced the now familiar scheme for keeping the peace of the world. The discussions had revealed many differences between the three great Allies, which will appear as this account proceeds. The Kremlin had no intention of joining an international body on which they would be out-voted by a host of small Powers, who, though they could not influence the course of the war, would certainly claim equal status in the victory. I felt sure we could only reach good decisions with Russia while we had the comradeship of a common foe as a bond. Hitler and Hitlerism were doomed; but after Hitler what?

We alighted at Moscow on the afternoon of October 9, and were received very heartily and with full ceremonial by Molotov and many high Russian personages. This time we were lodged in Moscow itself, with every care and comfort. I had one small, perfectly appointed house, and Anthony another near by. We were glad to dine alone together and rest. At ten o’clock that night we held our first important meeting in the Kremlin. There were only Stalin, Molotov, Eden, and I, with Major Birse and Pavlov as interpreters. It was agreed to invite the Polish Prime Minister, M. Romer, the Foreign Minister, and M. Grabski, a grey-bearded and aged academician of much charm and quality, to Moscow at once. I telegraphed accordingly to M. Mikolajczyk that we were expecting him and his friends for discussions with the Soviet Government and ourselves, as well as with the Lublin Polish Committee. I made it clear that refusal to come to take part in the conversations would amount to a definite rejection of our advice and would relieve us from further responsibility towards the London Polish Government.

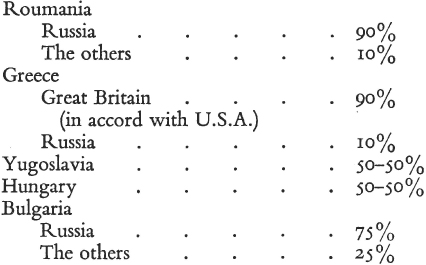

The moment was apt for business, so I said, “Let us settle about our affairs in the Balkans. Your armies are in Roumania and Bulgaria. We have interests, missions, and agents there. Don’t let us get at cross-purposes in small ways. So far as Britain and Russia are concerned, how would it do for you to have ninety per cent. predominance in Roumania, for us to have ninety per cent. of the say in Greece, and go fifty-fifty about Yugoslavia?” While this was being translated I wrote out on a half-sheet of paper:

I pushed this across to Stalin, who had by then heard the translation. There was a slight pause. Then he took his blue pencil and made a large tick upon it, and passed it back to us. It was all settled in no more time than it takes to set down.

Of course we had long and anxiously considered our point, and were only dealing with immediate war-time arrangements. All larger questions were reserved on both sides for what we then hoped would be a peace table when the war was won.

After this there was a long silence. The pencilled paper lay in the centre of the table. At length I said, “Might it not be thought rather cynical if it seemed we had disposed of these issues, so fateful to millions of people, in such an offhand manner? Let us burn the paper.” “No, you keep it,” said Stalin.

“It is absolutely necessary,” I reported privately to the President, “we should try to get a common mind about the Balkans, so that we may prevent civil war breaking out in several countries, when probably you and I would be in sympathy with one side and U.J. with the other. I shall keep you informed of all this, and nothing will be settled except preliminary agreements between Britain and Russia, subject to further discussion and melting down with you. On this basis I am sure you will not mind our trying to have a full meeting of minds with the Russians.”

After this meeting I reflected on our relations with Russia throughout Eastern Europe, and in order to clarify my ideas drafted a letter to Stalin on the subject, enclosing a memorandum stating our interpretation of the percentages which we had accepted across the table. In the end I did not send this letter, deeming it wiser to let well alone. I print it only as an authentic account of my thought.

Moscow

October 11, 1944

I deem it profoundly important that Britain and Russia should have a common policy in the Balkans which is also acceptable to the United States. The fact that Britain and Russia have a twenty-year alliance makes it especially important for us to be in broad accord and to work together easily and trustfully and for a long time. I realise that nothing we can do here can be more than preliminary to the final decisions we shall have to take when all three of us are gathered together at the table of victory. Nevertheless I hope that we may reach understandings, and in some cases agreements, which will help us through immediate emergencies, and will afford a solid foundation for long-enduring world peace.

These percentages which I have put down are no more than a method by which in our thoughts we can see how near we are together, and then decide upon the necessary steps to bring us into full agreement. As I said, they would be considered crude, and even callous, if they were exposed to the scrutiny of the Foreign Offices and diplomats all over the world. Therefore they could not be the basis of any public document, certainly not at the present time. They might however be a good guide for the conduct of our affairs. If we manage these affairs well we shall perhaps prevent several civil wars and much bloodshed and strife in the small countries concerned. Our broad principle should be to let every country have the form of government which its people desire. We certainly do not wish to force on any Balkan State monarchic or republican institutions. We have however established certain relations of faithfulness with the Kings of Greece and Yugoslavia. They have sought our shelter from the Nazi foe, and we think that when normal tranquillity is reestablished and the enemy has been driven out the peoples of these countries should have a free and fair chance of choosing. It might even be that Commissioners of the three Great Powers should be stationed there at the time of the elections so as to see that the people have a genuine free choice. There are good precedents for this.

However, besides the institutional question there exists in all these countries the ideological issue between totalitarian forms of government and those we call free enterprise controlled by universal suffrage. We are very glad that you have declared yourselves against trying to change by force or by Communist propaganda the established systems in the various Balkan countries. Let them work out their own fortunes during the years that lie ahead. One thing however we cannot allow—Fascism or Nazism in any of their forms, which give to the toiling masses neither the securities offered by your system nor those offered by ours, but, on the contrary, lead to the build-up of tyrannies at home and aggression abroad. In principle I feel that Great Britain and Russia should feel easy about the internal government of these countries, and not worry about them or interfere with them once conditions of tranquillity have been restored after this terrible blood-bath which they, and indeed we, have all been through.

It is from this point of view that I have sought to adumbrate the degrees of interest which each of us takes in these countries with the full assent of the other, and subject to the approval of the United States, which may go far away for a long time and then come back again unexpectedly with gigantic strength.

In writing to you, with your experience and wisdom, I do not need to go through a lot of arguments. Hitler has tried to exploit the fear of an aggressive, proselytising Communism which exists throughout Western Europe, and he is being decisively beaten to the ground. But, as you know well, this fear exists in every country, because, whatever the merits of our different systems, no country wishes to go through the bloody revolution which will certainly be necessary in nearly every case before so drastic a change could be made in the life, habits, and outlook of their society. At this point, Mr. Stalin, I want to impress upon you the great desire there is in the heart of Britain for a long, stable friendship and co-operation between our two countries, and that with the United States we shall be able to keep the world engine on the rails.

To my colleagues at home I sent the following:

12 Oct 44

The system of percentage is not intended to prescribe the numbers sitting on commissions for the different Balkan countries, but rather to express the interest and sentiment with which the British and Soviet Governments approach the problems of these countries, and so that they might reveal their minds to each other in some way that could be comprehended. It is not intended to be more than a guide, and of course in no way commits the United States, nor does it attempt to set up a rigid system of spheres of interest. It may however help the United States to see how their two principal Allies feel about these regions when the picture is presented as a whole.

2. Thus it is seen that quite naturally Soviet Russia has vital interests in the countries bordering on the Black Sea, by one of whom, Roumania, she has been most wantonly attacked with twenty-six divisions, and with the other of whom, Bulgaria, she has ancient ties. Great Britain feels it right to show particular respect to Russian views about these two countries, and to the Soviet desire to take the lead in a practical way in guiding them in the name of the common cause.

3. Similarly, Great Britain has a long tradition of friendship with Greece, and a direct interest as a Mediterranean Power in her future.… Here it is understood that Great Britain will take the lead in a military sense and try to help the existing Royal Greek Government to establish itself in Athens upon as broad and united a basis as possible. Soviet Russia would be ready to concede this position and function to Great Britain in the same sort of way as Britain would recognise the intimate relationship between Russia and Roumania. This would prevent in Greece the growth of hostile factions waging civil war upon each other and involving the British and Russian Governments in vexatious arguments and conflict of policy.

4. Coming to the case of Yugoslavia, the numerical symbol 50-50 is intended to be the foundation of joint action and an agreed policy between the two Powers now closely involved, so as to favour the creation of a united Yugoslavia after all elements there have been joined together to the utmost in driving out the Nazi invaders. It is intended to prevent, for instance, armed strife between the Croats and Slovenes on the one side and powerful and numerous elements in Serbia on the other, and also to produce a joint and friendly policy towards Marshal Tito, while ensuring that weapons furnished to him are used against the common Nazi foe rather than for internal purposes. Such a policy, pursued in common by Britain and Soviet Russia, without any thought of special advantages to themselves, would be of real benefit.

28*

5. As it is the Soviet armies which are obtaining control of Hungary, it would be natural that a major share of influence should rest with them, subject of course to agreement with Great Britain and probably the United States, who, though not actually operating in Hungary, must view it as a Central European and not a Balkan State.

6. It must be emphasised that this broad disclosure of Soviet and British feelings in the countries mentioned above is only an interim guide for the immediate war-time future, and will be surveyed by the Great Powers when they meet at the armistice or peace table to make a general settlement of Europe.

The Poles from London had now arrived, and at five o’clock on the evening of October 13 we assembled at the Soviet Government Hospitality House, known as Spiridonovka, to hear Mikolajczyk and his colleagues put their case. These talks were held as a preparation for a further meeting at which the British and American delegations would meet the Lublin Poles. I pressed Mikolajczyk hard to consider two things, namely, de facto acceptance of the Curzon Line,* with interchange of population, and a friendly discussion with the Lublin Polish Committee so that a united Poland might be established. Changes, I said, would take place, but it would be best if unity were established now, at this closing period of the war, and I asked the Poles to consider the matter carefully that night. Mr. Eden and I would be at their disposal. It was essential for them to make contact with the Polish Committee and to accept the Curzon Line as a working arrangement, subject to discussion at the Peace Conference.

At ten o’clock the same evening we met the so-called Polish National Committee. It was soon plain that the Lublin Poles were mere pawns of Russia, They had learned and rehearsed their part so carefully that even their masters evidently felt they were overdoing it. For instance, M. Bierut, the leader, spoke in these terms: “We are here to demand on behalf of Poland that Lvov shall belong to Russia. This is the will of the Polish people.” When this had been translated from Polish into English and Russian I looked at Stalin and saw an understanding twinkle in his expressive eyes, as much as to say, “What about that for our Soviet teaching!” The lengthy contribution of another Lublin leader, Osóbka-Morawski, was equally depressing. Mr. Eden formed the worst opinion of the three Lublin Poles.

The whole conference lasted over six hours, but the achievement was small, and as the days passed only slight improvement was made with the festering sore of Soviet-Polish affairs. The Poles from London were willing to accept the Curzon Line “as a line of demarcation between Russia and Poland”. The Russians insisted on the words “as a basis of frontier between Russia and Poland”. Neither side would give way. Mikolajczyk declared that he would be repudiated by his own people, and Stalin at the end of a talk of two hours and a quarter which I had with him alone remarked that he and Molotov were the only two of those he worked with who were favourable to dealing “softly” with Mikolajczyk. I was sure there were strong pressures in the background, both party and military.

Stalin was against trying to form a united Polish Government without the frontier question being agreed. Had this been settled he would have been quite willing that Mikolajczyk should head the new Government. I myself thought that difficulties not less obstinate would arise in a discussion for a merger of the Polish Government with the Lublin Poles, whose representatives continued to make the worst possible impression on us, and who, I told Stalin, were “only an expression of the Soviet will”. They had no doubt also the ambition to rule Poland, and were thus a kind of Quislings. In all the circumstances the best course was for the two Polish delegations to return whence they had come. I felt very deeply the responsibility which lay on me and the Foreign Secretary in trying to frame proposals for a Russo-Polish settlement. Even forcing the Curzon Line upon Poland would excite criticism.

In other directions considerable advantages had been gained. The resolve of the Soviet Government to attack Japan on the overthrow of Hitler was obvious. This would have supreme value in shortening the whole struggle. The arrangements made about the Balkans were, I was sure, the best possible. Coupled with successful military action, they should now be effective in saving Greece, and I had no doubt that our agreement to pursue a fifty-fifty joint policy in Yugoslavia was the best solution for our difficulties in view of Tito’s behaviour—having lived under our protection for three or four months, he had come secretly to Moscow to confer, without telling us where he had gone—and of the arrival of Russian and Bulgarian forces under Russian command to help his eastern flank.

There is no doubt that in our narrow circle we talked with an ease, freedom, and cordiality never before attained between our two countries. Stalin made several expressions of personal regard which I feel sure were sincere. But I became even more convinced that he was by no means alone. As I said to my colleagues at home, “Behind the horseman sits black care.”

On the evening of October 17 we held our last meeting. The news had just arrived that Admiral Horthy had been arrested by the Germans as a precaution now that the whole German front in Hungary was disintegrating. I remarked that I hoped the Ljubljana Gap could be reached as fast as possible, and added that I did not think the war would be over before the spring.