GLEAMING successes marked the end of our campaigns in the Mediterranean. In December Alexander had succeeded Wilson as Supreme Commander, while Mark Clark took command of the Fifteenth Army Group. After their strenuous efforts of the autumn our armies in Italy needed a pause to reorganise and restore their offensive power.

The long, obstinate, and unexpected German resistance on all fronts had made us and the Americans very short of artillery ammunition, and our hard experiences of winter campaigning in Italy forced us to postpone a general offensive till the spring. But the Allied Air Forces, under General Eaker, and later under General Cannon, used their thirty-to-one superiority in merciless attacks on the supply lines which nourished the German armies. The most important one, from Verona to the Brenner Pass, where Hitler and Mussolini used to meet in their happier days, was blocked in many places for nearly the whole of March. Other passes were often closed for weeks at a time, and two divisions being transferred to the Russian front were delayed almost a month.

The enemy had enough ammunition and supplies, but lacked fuel. Units were generally up to strength, and their spirit was high in spite of Hitler’s reverses on the Rhine and the Oder. The German High Command might have had little to fear had it not been for the dominance of our Air Forces, the fact that we had the initiative and could strike where we pleased, and their own ill-chosen defensive position, with the broad Po at their backs. They would have done better to yield Northern Italy and withdraw to the strong defences of the Adige, where they could have held us with much smaller forces, and sent troops to help their over-matched armies elsewhere, or have made a firm southern face for the National Redoubt in the Tyrol mountains, which Hitler may have had in mind as his “last ditch”.

But defeat south of the Po spelt disaster. This must have been obvious to Kesselring, and was doubtless one of the reasons for the negotiations recorded in the previous chapter. Hitler was of course the stumbling-block and when Vietinghoff, who succeeded Kesselring, proposed a tactical withdrawal he was thus rebuffed: “The Fuehrer expects, now as before, the utmost steadiness in the fulfilment of your present mission to defend every inch of the North Italian areas entrusted to your command.”

In the evening of April 9, after a day of mass air attacks and artillery bombardment, the Eighth Army attacked. By the 14th there was good news all along the front. The Fifth Army, after a week of hard fighting, backed by the full weight of the Allied Air Forces, broke out from the mountains, crossed the main road west of Bologna, and struck north. On the 20th Vietinghoff, despite Hitler’s commands, ordered a withdrawal. It was too late. The Fifth Army pressed towards the Po, with the Tactical Air Force making havoc along the roads ahead. Trapped behind them were many thousand Germans, cut off from retreat, pouring into prisoners’ cages or being marched to the rear. We crossed the Po on a broad front at the heels of the enemy. All the permanent bridges had been destroyed by our Air Forces, and the ferries and temporary crossings were attacked with such effect that the enemy were thrown into confusion. The remnants who struggled across, leaving all their heavy equipment behind, were unable to reorganise on the far bank. The Allied armies pursued them to the Adige. Italian Partisans had long harassed the enemy in the mountains and their back areas. On April 25 the signal was given for a general rising and they made widespread attacks. In many cities and towns, notably Milan and Venice, they seized control. Surrenders in North-West Italy became wholesale. The garrison of Genoa, four thousand strong, gave themselves up to a British liaison officer and the Partisans.

There was a pause before the force of facts overcame German hesitancies, but on April 24 Wolff reappeared in Switzerland with full powers from Vietinghoff. Two plenipotentiaries were brought to Alexander’s headquarters, and on April 29 they signed the instrument of unconditional surrender in the presence of high British, American, and Russian officers. On May 2 nearly a million Germans surrendered as prisoners of war, and the war in Italy ended.

Thus ended our twenty months’ campaign. Our losses had been grievous, but those of the enemy, even before the final surrender, far heavier. The principal task of our armies had been to draw off and contain the greatest possible number of Germans. This had been admirably fulfilled. Except for a short period in the summer of 1944, the enemy had always outnumbered us. At the time of their crisis in August of that year no fewer than fifty-five German divisions were deployed along the Mediterranean fronts. Nor was this all. Our forces rounded off their task by devouring the larger army they had been ordered to contain. There have been few campaigns with a finer culmination.

For Mussolini also the end had come. Like Hitler he seems to have kept his illusions until almost the last moment. Late in March he had paid a final visit to his German partner, and returned to his headquarters on Lake Garda buoyed up with the thought of the secret weapons which could still lead to victory. But the rapid Allied advance from the Apennines made these hopes vain. There was hectic talk of a last stand in the mountainous areas of the Italo-Swiss frontier. But there was no will to fight left in the Italian Socialist Republic.

On April 25 Mussolini decided to disband the remnants of his armed forces and to ask the Cardinal Archbishop of Milan to arrange a meeting with the underground Military Committee of the Italian National Liberation Movement. That afternoon talks took place in the Archbishop’s palace, but with a last furious gesture of independence Mussolini walked out. In the evening, followed by a convoy of thirty vehicles, containing most of the surviving leaders of Italian Fascism, he drove to the prefecture at Como. He had no coherent plan, and as discussion became useless it was each man for himself. Accompanied by a handful of supporters, he attached himself to a small German convoy heading towards the Swiss frontier. The commander of the column was not anxious for trouble with Italian Partisans. The Duce was persuaded to put on a German great-coat and helmet. But the little party was stopped by Partisan patrols; Mussolini was recognised and taken into custody. Other members, including his mistress, Signorina Petacci, were also arrested. On Communist instructions the Duce and his mistress were taken out in a car next day and shot. Their bodies, together with others, were sent to Milan and strung up head downwards on meat-hooks in a petrol station on the Piazzale Loreto, where a group of Italian Partisans had lately been shot in public.

Such was the fate of the Italian dictator. A photograph of the final scene was sent to me, and I was profoundly shocked. But at least the world was spared an Italian Nuremberg.

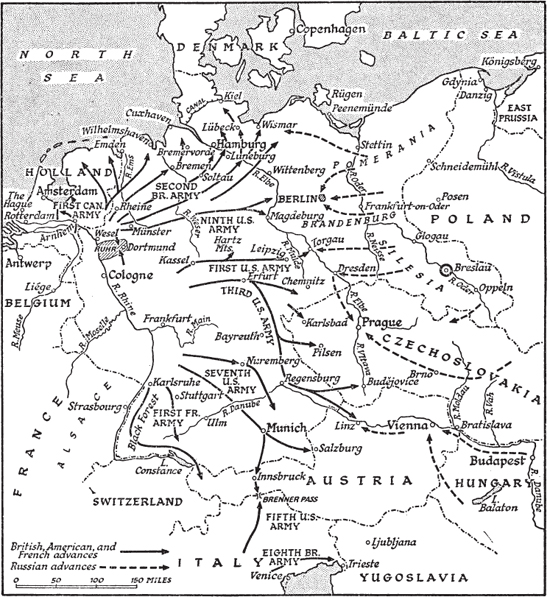

In Germany the invading armies drove onwards in their might and the space between them narrowed daily. By early April Eisenhower was across the Rhine and thrusting deep into Germany and Central Europe against an enemy who in places resisted fiercely but was quite unable to stem our triumphant onrush. Many political and military prizes still hung in the balance. Poland was beyond our succour. So also was Vienna, where our opportunity of forestalling the Russians by an advance from Italy had been abandoned eight months earlier when Alexander’s forces had been stripped for the landing in the south of France. The Russians moved on the city from east and south, and by April 13 were in full possession. But there seemed nothing to stop the Western Allies from taking Berlin. The Russians were only thirty-five miles away, but the Germans were entrenched on the Oder and much hard fighting was to take place before they could force a crossing and resume their advance. The Ninth U.S. Army, on the other hand, had moved so speedily that on April 12 they had crossed the Elbe near Magdeburg and were about sixty miles from the capital. But here they halted. Four days later the Russians started their attack and surrounded Berlin on the 25th. Stalin had told Eisenhower that his main blow against Germany would be made in “approximately the second half of May”, but he was able to advance a whole month earlier. Perhaps our swift approach to the Elbe had something to do with it.

On this same 25th day of April, 1945, spearheads of the United States First Army from Leipzig met the Russians near Torgau, on the Elbe. Germany was cut in two. The German Army was disintegrating before our eyes. Over a million prisoners were taken in the first three weeks of April, but Eisenhower believed that fanatical Nazis would attempt to establish themselves in the mountains of Bavaria and Western Austria, and he swung the Third U.S. Army southwards. Its left penetrated into Czechoslovakia as far as Budĕjovice, Pilsen, and Karlsbad. Prague was still within our reach and there was no agreement to debar him from occupying it if it were militarily feasible. On April 30 I suggested to the President that he should do so, but Mr. Truman seemed adverse. A week later I also telegraphed personally to Eisenhower, but his plan was to halt his advance generally on the west bank of the Elbe and along the 1937 boundary of Czechoslovakia. If the situation warranted he would cross it to the general line Karlsbad-Pilsen-Budĕjovice. The Russians agreed to this and the movement was made. But on May 4 they reacted strongly to a fresh proposal to continue the advance of the Third U.S. Army to the river Vltava, which flows through Prague. This would not have suited them at all. So the Americans “halted while the Red Army cleared the east and west banks of the Moldau river and occupied Prague”.* The city fell on May 9, two days after the general surrender was signed at Rheims.

At this point a retrospect is necessary. The occupation of Germany by the principal Allies had long been studied. In the summer of 1943 a Cabinet Committee which I had set up under Mr. Attlee, in agreement with the Chiefs of Staff, recommended that the whole country should be occupied if Germany was to be effectively disarmed, and that our forces should be disposed in three main zones of roughly equal size the British in the north-west, the Americans in the south and south-west, and the Russians in the eastern zone. Berlin should be a separate joint zone, occupied by each of the three major Allies. These recommendations were approved and forwarded to the European Advisory Council, which then consisted of M. Gousev, the Soviet Ambassador, Mr. Winant, the American Ambassador, and Sir William Strang of the Foreign Office.

30*

At this time the subject seemed to be purely theoretical. No one could foresee when or how the end of the war would come. The German armies held immense areas of European Russia. A year was yet to pass before British or American troops set foot in Western Europe, and nearly two years before they entered Germany. The proposals of the European Advisory Council were not thought sufficiently pressing or practical to be brought before the War Cabinet. Like many praiseworthy efforts to make plans for the future, they lay upon the shelves while the war crashed on. In those days a common opinion about Russia was that she would not continue the war once she had regained her frontiers, and that when the time came the Western Allies might well have to try to persuade her not to relax her efforts. The question of the Russian zone of occupation in Germany therefore did not bulk in our thoughts or in Anglo-American discussions, nor was it raised by any of the leaders at Teheran.

When we met in Cairo on the way home in November 1943 the United States Chiefs of Staff brought it forward, but not on account of any Russian request. The Russian zone of Germany remained an academic conception, if anything too good to be true. I was however told that President Roosevelt wished the British and American zones to be reversed. He wanted the lines of communication of any American force in Germany to rest directly on the sea and not to run through France. This issue involved a lot of detailed technical argument and had a bearing at many points upon the plans for “Overlord”. No decision was reached at Cairo, but later a considerable correspondence began between the President and myself. The British Staff thought the original plan the better, and also saw many inconveniences and complications in making the change. I had the impression that their American colleagues rather shared their view. At the Quebec Conference in September 1944 we reached a firm agreement between us.

The President, evidently convinced by the military view, had a large map unfolded on his knees. One afternoon, most of the Combined Chiefs of Staff being present, he agreed verbally with me that the existing arrangement should stand subject to the United States armies having a near-by direct outlet to the sea across the British zone. Bremen and its subsidiary Bremerhaven seemed to meet the American needs, and their control over this zone was adopted. This decision is illustrated on the accompanying map. We all felt it was too early as yet to provide for a French zone in Germany, and no one as much as mentioned Russia.

At Yalta in February 1945 the Quebec plan was accepted without further consideration as the working basis for the inconclusive discussions about the future eastern frontier of Germany. This was reserved for the Peace Treaty. The Soviet armies were at this very moment swarming over the pre-war frontiers, and we wished them all success. We proposed an agreement about the zones of occupation in Austria. Stalin, after some persuasion, agreed to my strong appeal that the French should be allotted part of the American and British zones and given a seat on the Allied Control Commission. It was well understood by everyone that the agreed occupational zones must not hamper the operational movements of the armies. Berlin, Prague, and Vienna could be taken by whoever got there first. We separated in the Crimea not only as Allies but as friends facing a still mighty foe with whom all our armies were struggling in fierce and ceaseless battle.

The two months that had passed since then had seen tremendous changes cutting to the very roots of thought. Hitler’s Germany was doomed and he himself about to perish. The Russians were fighting in Berlin. Vienna and most of Austria was in their hands. The whole relationship of Russia with the Western Allies was in flux. Every question about the future was unsettled between us. The agreements and understandings of Yalta, such as they were, had already been broken or brushed aside by the triumphant Kremlin. New perils, perhaps as terrible as those we had surmounted, loomed and glared upon the torn and harassed world.

My concern at these ominous developments was apparent even before the President’s death. He himself, as we have seen, was also anxious and disturbed. His anger at Molotov’s accusations over the Berne affair has been recorded. In spite of the victorious advance of Eisenhower’s armies, President Truman found himself faced in the last half of April with a formidable crisis. I had for some time past tried my utmost to impress the United States Government with the vast changes which were taking place both in the military and political spheres. Our Western armies would soon be carried well beyond the boundaries of our occupation zones, as both the Western and Eastern Allied fronts approached one another, penning the Germans between them.

Telegrams which I have published elsewhere show that I never suggested going back on our word over the agreed zones provided other agreements were also respected. I became convinced however that before we halted, or still more withdrew, our troops, we ought to seek a meeting with Stalin face to face and make sure that an agreement was reached about the whole front. It would indeed be a disaster if we kept all our agreements in strict good faith while the Soviets laid their hands upon all they could get without the slightest regard for the obligations into which they had entered.

General Eisenhower had proposed that while the armies in the west and the east should advance irrespective of demarcation lines, in any area where the armies had made contact either side should be free to suggest that the other should withdraw behind the boundaries of their occupation zone. Discretion to request and to order such withdrawals would rest with Army Group commanders. Subject to the dictates of operational necessity, the retirement would then take place. I considered that this proposal was premature and that it exceeded the immediate military needs. Action was taken accordingly, and on April 18 I addressed myself to the new President. Mr. Truman was of course only newly aware at second hand of all the complications that faced us, and had to lean heavily on his advisers. The purely military view therefore received an emphasis beyond its proper proportion. I cabled him as follows:

… I am quite prepared to adhere to the occupational zones, but I do not wish our Allied troops or your American troops to be hustled back at any point by some crude assertion of a local Russian general. This must be provided against by an agreement between Governments so as to give Eisenhower a fair chance to settle on the spot in his own admirable way.

… The occupational zones were decided rather hastily at Quebec in September 1944, when it was not foreseen that General Eisenhower’s armies would make such a mighty inroad into Germany. The zones cannot be altered except by agreement with the Russians. But the moment V.E. Day [Victory in Europe Day] has occurred we should try to set up the Allied Control Commission in Berlin and should insist upon a fair distribution of the food produced in Germany between all parts of Germany. As it stands at present the Russian occupational zone has the smallest proportion of people and grows by far the largest proportion of food, the Americans have a not very satisfactory proportion of food to conquered population, and we poor British are to take over all the ruined Ruhr and large manufacturing districts, which are, like ourselves, in normal times large importers of food.…

Mr. Eden was in Washington, and fully agreed with the views I telegraphed to him, but Mr. Truman’s reply carried us little further. He proposed that the Allied troops should retire to their agreed zones in Germany and Austria as soon as the military situation allowed.

Hitler had meanwhile pondered where to make his last stand. As late as April 20 he still thought of leaving Berlin for the “Southern Redoubt” in the Bavarian Alps. That day he held a meeting of the principal Nazi leaders. As the German double front, East and West, was in imminent danger of being cut in twain by the spearpoint thrust of the Allies, he agreed to set up two separate commands. Admiral Doenitz was to take charge in the North both of the military and civil authorities, with the particular task of bringing back to German soil nearly two million refugees from the East. In the South General Kesselring was to command the remaining German armies. These arrangements were to take effect if Berlin fell.

Two days later, on April 22, Hitler made his final and supreme decision to stay in Berlin to the end. The capital was soon completely encircled by the Russians and the Fuehrer had lost all power to control events. It remained for him to organise his own death amid the ruins of the city. He announced to the Nazi leaders who remained with him that he would die in Berlin. Goering and Himmler had both left after the conference of the 20th, with thoughts of peace negotiations in their minds. Goering, who had gone south, assumed that Hitler had in fact abdicated by his resolve to stay in Berlin, and asked for confirmation that he should act formally as the successor to the Fuehrer. The reply was his instant dismissal from all his offices. In a remote mountain village of the Tyrol he and nearly a hundred of the more senior officers of the Luftwaffe were taken prisoner by the Americans. Retribution had come at last.

The last scenes at Hitler’s headquarters have been described elsewhere in much detail. Of the personalities of his régime only Goebbels and Bormann remained with him to the end. The Russian troops were now fighting in the streets of Berlin. In the early hours of April 29 Hitler made his will. The day opened with the normal routine of work in the air-raid shelter under the Chancellery. News arrived of Mussolini’s end. The timing was grimly appropriate. On the 30th Hitler lunched quietly with his suite, and at the end of the meal shook hands with those present and retired to his private room. At half-past three a shot was heard, and members of his personal staff entered the room to find him lying on the sofa with a revolver by his side. He had shot himself through the mouth. Eva Braun, whom he had married secretly during these last days, lay dead beside him. She had taken poison. The bodies were burnt in the courtyard, and Hitler’s funeral pyre, with the din of the Russian guns growing ever louder, made a lurid end to the Third Reich.

The leaders who were left held a final conference. Last-minute attempts were made to negotiate with the Russians, but Zhukov demanded unconditional surrender. Bormann tried to break through the Russian lines, and disappeared without trace. Goebbels poisoned his six children and then ordered an S.S. guard to shoot his wife and himself. The remaining staff of Hitler’s headquarters fell into Russian hands.

That evening a telegram reached Admiral Doenitz at his headquarters in Holstein:

In place of the former Reich-Marshal Goering the Fuehrer appoints you, Herr Grand Admiral, as his successor. Written authority is on its way. You will immediately take all such measures as the situation requires. BORMANN.

Chaos descended. Doenitz had been in touch with Himmler, who, he assumed, would be nominated as Hitler’s successor if Berlin fell, and now supreme authority was suddenly thrust upon him without warning and he faced the task of organising the surrender.

For Himmler a less spectacular end was reserved. He had gone to the Eastern Front and for some months had been urged to make personal contact with the Western Allies on his own initiative in the hope of negotiating a separate surrender. He now tried to do so through Count Bernadotte, the head of the Swedish Red Cross, but we repulsed his offers. No more was heard of him till May 21, when he was arrested by a British control post at Bremervörde. He was disguised and was not recognised, but his papers made the sentries suspicious and he was taken to a camp near Second Army Headquarters. He then told the commandant who he was. He was put under armed guard, stripped, and searched for poison by a doctor. During the final stage of the examination he bit open a phial of cyanide, which he had apparently hidden in his mouth for some hours. He died almost instantly, just after eleven o’clock at night on Wednesday, May 23.

In the north-west the drama closed less sensationally. On May 2 news arrived of the surrender in Italy. On the same day our troops reached Lübeck, on the Baltic, making contact with the Russians and cutting off all the Germans in Denmark and Norway. On the 3rd we entered Hamburg without opposition and the garrison surrendered unconditionally. A German delegation came to Montgomery’s headquarters on Luneberg Heath. It was headed by Admiral Friedeburg, Doenitz’s emissary, who sought a surrender agreement to include German troops in the North who were facing the Russians. This was rejected as being beyond the authority of an Army Group commander, who could deal only with his own front. Next day, having received fresh instructions from his superiors, Friedeburg signed the surrender of all German forces in North-West Germany, Holland, the Islands, Schleswig-Holstein, and Denmark.

Friedeburg went on to Eisenhower’s headquarters at Rheims, where he was joined by General Jodl on May 6. They played for time to allow as many soldiers and refugees as possible to disentangle themselves from the Russians and come over to the Western Allies and they tried to surrender the Western Front separately. Eisenhower imposed a timelimit and insisted on a general capitulation. Jodl reported to Doenitz: “General Eisenhower insists that we sign to-day. If not, the Allied fronts will be closed to persons seeking to surrender individually. I see no alternative—chaos or signature. I ask you to confirm to me immediately by wireless that I have full powers to sign capitulation.”

The instrument of total, unconditional surrender was signed by Lieut.-General Bedell Smith and General Jodl, with French and Russian officers as witnesses, at 2.41 a.m., on May 7. Thereby all hostilities ceased at midnight on May 8. The formal ratification by the German High Command took place in Berlin, under Russian arrangements, in the early hours of May 9. Air Chief Marshal Tedder signed on behalf of Eisenhower, Marshal Zhukov for the Russians, and Field-Marshal Keitel for Germany.

The immense scale of events on land and in the air has tended to obscure the no less impressive victory at sea. The whole Anglo-American campaign in Europe depended upon the movement of convoys across the Atlantic, and we may here carry the story of the U-boats to its conclusion. In spite of appalling losses to themselves they continued to attack, but with diminishing success, and the flow of shipping was unchecked. Even after the autumn of 1944, when they were forced to abandon their bases in the Bay of Biscay, they did not despair. The Schnorkel-fitted boats now in service, breathing through a tube while charging their batteries submerged, were but an introduction to the new pattern of U-boat warfare which Doenitz had planned. He was counting on the advent of the new type of boat, of which very many were now being built, and the first were already under trial. Their high submerged speed threatened us with new problems, and would indeed, as Doenitz predicted, have revolutionised U-boat warfare. His plans failed mainly because the special materials needed to construct these vessels became very scarce and their design had constantly to be changed. But ordinary U-boats were still being made piecemeal all over Germany and assembled in bomb-proof shelters at the ports, and in spite of the intense and continuing efforts of Allied bombers the Germans built more submarines in November 1944 than in any other month of the war. By stupendous efforts and in spite of all losses about sixty or seventy U-boats remained in action until almost the end. Their achievements were not large, but they carried the undying hope of stalemate at sea. The new revolutionary submarines never played their part in the Second World War. It had been planned to complete 350 of them during 1945, but only a few came into service before the capitulation. This weapon in Soviet hands lies among the hazards of the future.

Allied air attacks destroyed many U-boats at their berths. Nevertheless when Doenitz ordered them to surrender no fewer than forty-nine were still at sea. Over a hundred more gave themselves up in harbour, and about two hundred and twenty were scuttled or destroyed by their crews. Such was the persistence of Germany’s effort and the fortitude of the U-boat service.

In sixty-eight months of fighting 781 German U-boats were lost. For more than half this time the enemy held the initiative. After 1942 the tables were turned; the destruction of U-boats rose and our losses fell. In the final count British and British-controlled forces destroyed 500 out of the 632 submarines known to have been sunk at sea by the Allies.

In the First World War eleven million tons of shipping were sunk, and in the second fourteen and a half million tons, by U-boats alone. If we add the loss from other causes the totals become twelve and three-quarter million and twenty-one and a half million. Of this the British bore over 60 per cent. in the first war and over half in the second.

The unconditional surrender of our enemies was the signal for the greatest outburst of joy in the history of mankind. The Second World War had indeed been fought to the bitter end in Europe. The vanquished as well as the victors felt inexpressible relief. But for us in Britain and the British Empire, who had alone been in the struggle from the first day to the last and staked our existence on the result, there was a meaning beyond what even our most powerful and most valiant Allies could feel. Weary and worn, impoverished but undaunted and now triumphant, we had a moment that was sublime. We gave thanks to God for the noblest of all His blessings, the sense that we had done our duty.

When in these tumultuous days of rejoicing I was asked to speak to the nation I had borne the chief responsibility in our Island for almost exactly five years. Yet it may well be there were few whose hearts were more heavily burdened with anxiety than mine. After reviewing the varied tale of our fortunes I struck a sombre note which may be recorded here.

“I wish,” I said, “I could tell you to-night that all our toils and troubles were over. Then indeed I could end my five years’ service happily, and if you thought that you had had enough of me and that I ought to be put out to grass I would take it with the best of grace. But, on the contrary, I must warn you, as I did when I began this five years’ task—and no one knew then that it would last so long—that there is still a lot to do, and that you must be prepared for further efforts of mind and body and further sacrifices to great causes if you are not to fall back into the rut of inertia, the confusion of aim, and the craven fear of being great. You must not weaken in any way in your alert and vigilant frame of mind. Though holiday rejoicing is necessary to the human spirit, yet it must add to the strength and resilience with which every man and woman turns again to the work they have to do, and also to the outlook and watch they have to keep on public affairs.

“On the continent of Europe we have yet to make sure that the simple and honourable purposes for which we entered the war are not brushed aside or overlooked in the months following our success, and that the words ‘freedom’, ‘democracy’, and ‘liberation’ are not distorted from their true meaning as we have understood them. There would be little use in punishing the Hitlerites for their crimes if law and justice did not rule, and if totalitarian or police Governments were to take the place of the German invaders. We seek nothing for ourselves. But we must make sure that those causes which we fought for find recognition at the peace table in facts as well as words, and above all we must labour to ensure that the World Organisation which the United Nations are creating at San Francisco does not become an idle name, does not become a shield for the strong and a mockery for the weak. It is the victors who must search their hearts in their glowing hours, and be worthy by their nobility of the immense forces that they wield.

“We must never forget that beyond all lurks Japan, harassed and failing, but still a people of a hundred millions, for whose warriors death has few terrors. I cannot tell you to-night how much time or what exertions will be required to compel the Japanese to make amends for their odious treachery and cruelty. We, like China, so long undaunted, have received horrible injuries from them ourselves, and we are bound by the ties of honour and fraternal loyalty to the United States to fight this great war at the other end of the world at their side without flagging or failing. We must remember that Australia and New Zealand and Canada were and are all directly menaced by this evil Power. These Dominions come to our aid in our dark times, and we must not leave unfinished any task which concerns their safety and their future. I told you hard things at the beginning of these last five years; you did not shrink, and I should be unworthy of your confidence and generosity if I did not still cry: Forward, unflinching, unswerving, indomitable, till the whole task is done and the whole world is safe and clean.”