If monsters appear in all civilizations, in all epochs, and in the thoughts of “normal” people as well the fantasies of neurotics, it is because monsters perform a natural function!

—Claude Kappler; Monstres, démons et merveilles à la fin du Moyen Age

We have already encountered ritual monsters, by which I mean scary effigies or statues used in public festivities: figures of a horrible mien that are brought out to frighten or to instruct people, that is, ceremonial paraphernalia. Such would include the hideous masks the Sri Lankans use to exorcize devils and the colorful Kachina costumes the Hopi use to frighten neophytes during initiations. The ubiquity of such rite fright shows that the awful visions of the mind are wont to take concrete form and to engage with humans under controlled circumstances.

We have seen that since prehistoric times the monster’s therapeutic function is to give shape to deep-seated fears in objectified, manipulable forms, pictorially, as dramatis personae in theatrical productions, or as automated effigies that can interact with humans in choreographed narratives. In this way we reify the inner demon: magically make the monster real, externalize it, animate it, and persecute it. Ritualized monsters of this sort are one way a culture can work to sublimate instinct, just as in modern America we have celluloid extraterrestrials and Halloween ghouls.

One of the first anthropologists to explore the ritual realm of monsters was Victor Turner, whose groundbreaking works have become classics known to every graduate student. In a famous book on symbolism in tribal Africa, he analyzes demonic figures in the ceremonies of the Ndembu, a horticultural tribe of northwestern Zambia. Employing Van Gennep’s insights, Turner argues that the rites-of-passage of such preliterate peoples create what he calls a liminal time, an out-of-the ordinary “betwixt-and-between” period (1967: 93) when the rules are overturned and anything can happen. In times of liminality, neophytes are subjected to special shocks designed to awaken them to the meaning of their culture. For example, they may experience bizarre visions arranged by their elders: lurid masks and effigies that cavort menacingly. Prime among such oddities in Ndembu culture are costumed monsters: half-human creatures of threatening aspect.

According to Turner, the sudden appearance of these monsters traumatizes the neophytes and causes them to wonder and reflect. This enacts a cognitive transformation by which the young can reenter the world with greater understanding and a deeper commitment to their culture. Upon examining the ritual paraphernalia of the Ndembu, for example, Turner remarks he was often struck by the grotesqueness of the costumes worn by the actors. The young people are confronted by a cavorting half-human, half-lion figure that lunges wildly as if to devour them. Other oddities abound in the Ndembu sacra: hideous zombies, semi-human creatures with tiny heads and misshapen genitals, ugly ghouls sporting disproportionately large or small limbs, wraiths without heads, frightening zoomorphs, and the like.

Earlier anthropologists—such as J. A. McCulloch in a pioneering article on “Monsters” in the Hastings Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics—also noted the richness of African monster imagery. Like others at the time, McCulloch ascribed the African masks and costumed monstrosities to “hallucinations, night-terrors and dreams,” which he supposed tribal Africans were prone to. Extrapolating further, McCulloch argued that such images reflect the mental differences between civilized and primitive peoples: “as man drew little distinction [in primitive society] between himself and animals, as he thought that transformation from one to the other was possible, so he easily ran human and animal together. This in part accounts for the animal-headed gods or animal-gods with human heads” (cited in Turner 1967: 104–5).

Disagreeing with this ethnocentric reasoning, Turner argues that the monstrous figures are not merely nightmares proceeding from the primitive brain but rather didactic devices. Lovingly constructed by local artists, they are used to teach the neophytes to distinguish clearly between the different elements of reality, as it is conceived in their culture (1967: 105). For Turner, as for others who have embraced his insights, the African costumes and sacra represent the people’s inherent need to deal with and control the unimaginable and unknown in the world—that which exists “outside” the culture. From this standpoint, the use of the grotesque and monstrous images in such ceremonies may be interpreted as a means not so much of terrorizing young people (although this happens) as of awakening them to their own values and moral traditions: making them vividly and rapidly aware of what may be called the factors of their culture.

Thus the young people learn about the constituent elements of their world, and they are alternately forced and encouraged to think about their society, to consider the known cosmos and the powers that give them sustenance. For Turner, ritual monsters are metaphorical devices to encourage reflection and insight, ways of breaking down the normal into its component parts and reassembling them in new, exciting, even liberating ways. Effigy ogres are therefore not just fright masks, but the very stuff of the creative process, providing an experience necessary to human cognitive development. The terrible Ndembu were-lion encourages the observer to think about real lions, their habits and qualities, their metaphorical properties, religious significance, and so on. Even more than this, the relation between human beings and the real lion itself, and between the empirical and the metaphorical, may be speculated upon, and new ideas developed. Turner argues that monsters in the liminal period of the Ndembu ritual break, as it were, “the cake of custom” (106).

Although effigy monsters of this sort are perhaps represented most richly in the world’s preliterate cultures with their ritual repertories, they are not unique to tribal folk. This kind of outré ritual object also abounds in the heart of western Europe—especially in rural areas—even today. Ritualized monsters and demons are particularly pronounced in the parochial village festivals of southern France and Spain, paramount among which is the Spanish Tarasca (Tarasque in French), the monster-serpent of Catholic demonology. Its cult reaches an apogee today in northern Spain in the region of Catalonia.

Before getting to the Spanish Tarasca, we must take notice of the hundreds of demons, devils, and other kinds of costumed monsters that cavort and threaten during village festivals throughout Spain—a colorful Catholic mumming tradition that goes back at least to medieval days and shows the staying power of monstrous forms and images. Spain is in fact known throughout Europe for the persistence of its ritual clowns and devilish effigies, for which there are faint echoes in the rest of modern Western Europe, where perhaps science fiction literature and films have taken over this function. Many religious rituals in the rural Spanish pueblos feature mythic demons, “mimetic creatures,” in Guard’s words, and weird cryptomorphs such as minotaurs, menacing giants armed with spears and swords, cannibal ogres, outsized rams and goats, or deformed bulls (given the Spanish obsession with tauromachy). At the high point of these festivals, such figures (usually local men in costume, although sometimes mechanical devices are used) burst out of dark corners, set violently upon the bystanders, symbolically “eat” children, reducing the little ones to tears, and are finally defeated by a choreographed counterattack of the villagers—in the typical epic-hero mold we have seen so many times above. Some students of Spanish culture, like Carrie Douglass (1997) and Timothy Mitchell (1988,1990,1991), have even seen the Spanish corrida, the bullfight itself, as a reenactment of man-against-monster motif of classical antiquity. After all, the Spanish fighting bull is in some ways an unnatural and even monstrous creation, artificially outsized, produced through centuries of selective breeding and imbued with an abnormal ferocity. Mitchell (1988, 1990) refers to this tendency in Spanish culture as the “festival canalization of aggression,” which he argues is the underlying national genius of liminality in rites and celebrations. Based on these persuasive observations, one may argue that the inner logic of the Spanish man-against-beast rituals parallels the therapeutic and restorative functions of the monster legend in oral and written folklore the world over. Let us briefly examine some of these events in calendar order.

Our first stop is the town of Riofrío de Aliste, in Zamora Province in northwestern Spain, where on the first day of each year people celebrate the festival of La Obisparra, or the Mock Bishop’s Parade. This New Year’s event features jumping devils and demons called garochos, armed with gigantic pincers tipped with goat horns, that prance about town until surrounded and defeated by the villagers. On both January 1 and 6 there is a similar event in the nearby town of Montamarta. A devilish figure called a quinto (literally a recruit, but here meaning a local man playing the monster) goes around town chasing people, pretending to eat children, and generally behaving like a wild animal. After a full day of this bedlam, the quinto is surrounded and symbolically dispatched by the populace.

In southeastern Spain, in the small town of Piornal (Cáceres Province, Extremadura) the people celebrate a similar fiesta called Jarramplas (Devil-Clown) on January 19 and 20. In this persecutory masquerade, which is held in honor of Saint Sebastian, the jarramplas (a local term) is a similarly attired monster figure. Wearing a horned mask and a multi-colored devil’s costume, this hybrid beast goes around town playing a drum and frightening people by engaging in mock violence. According to ethnographer Javier Marcos Arévalo, who has studied zoomorphic imagery in Spanish festivals, the jarramplas figure has the special function of attacking all those who cross its path during the liminal festival period, “especially young people, and in particular young girls,” thus lending the celebration a distinctly erotic excitement (2001: 18). The jarramplas masquerader sports a padded head-to-toe costume to protect him from the avalanche of rotten fruit and vegetables that the townspeople hurl at him as he cavorts. Local people say that the monster represents all the evil in the world and must be “killed” by the barrage of objects—a symbolic stoning by which the villagers get rid of their sins for one year.

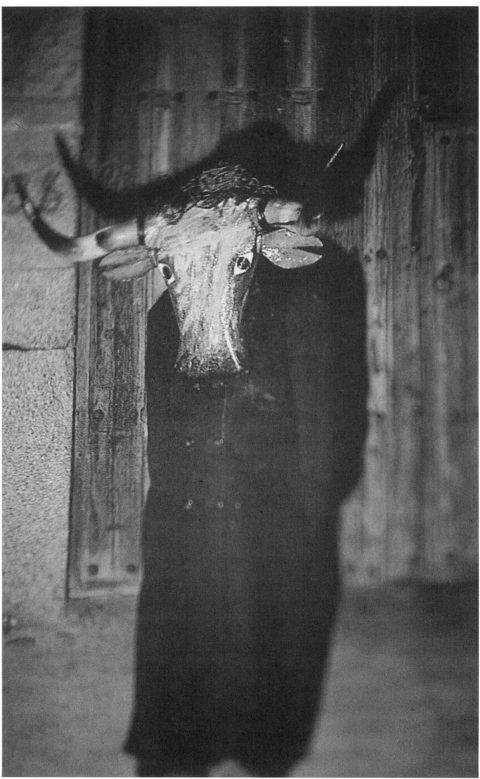

Carnival Minotaur figure “La Vaca Bayona,” Pereruela de Sauyago, Extremadura, Spain. Photo by Maria del Carmen Medina.

Another demonic fiesta takes place in the town of Arbancón, in Guadalajara Province in northern Spain. This event, called El Botarga de la Can-delaria (the Devil of Candlemas), takes place annually on the first Sunday in February. On a similar note of communal expiation, it features grotesque demons and zoomorphs (local volunteers in costume) who fight the villagers and pretend to eat children. They also go around town stealing objects and behaving with atavistic abandon. As in the events described previously, they are once again defeated by the multitudes in a ritual death symbolizing the defeat of all evil and the renewal of hope for the new year.

Later in February the various pre-Lenten carnivals in Spain also feature a plethora of demonic images and scary paraphernalia. Although carnival celebrations occur throughout Catholic Europe and Latin America, Spanish pueblo carnivals stand out because they often feature hideous creatures that ramble around town attacking or challenging people and enacting all sorts of nasty depredations. The carnivals of Bielsa (Huesca Province), Frontera (El Hieiro), and Fuentes de Andalucía (Seville) are good examples of this symbolic aggression. All three have traditions of unbridled devils and frisky, brutish monsters in their celebrations. In the Bielsa festival masked demons wearing huge horns and armed with stakes and poles attack the townspeople, sending the children into gales of hysteria. During the carnival of the village of Frontera in the Canary Islands, there occurs the liminal period called Los Carneros, or the Rams. In this event, local youths disguise themselves as monster-rams, wearing sheepskins, placing wicker baskets on their heads to form a huge sheep’s head with great, pointy horns, and painting their arms and legs black. They run up and down the streets attacking young boys and girls (García Rodero 1992: 275). The children are duly impressed, many bursting into tears at the sight of the threatening creatures.

In the Andalusian town of Fuentes, which I studied personally for many years (Gilmore 1998), carnival masquerades feature monstrous female figures that look something like a cross between a witch and a demon, and are armed with various weapons. These horrible apparitions march up and down through the winding streets at night seeking victims to attack, which they do with a ferocious mock violence bordering on the real, as well as a battery of verbal assaults. Sometimes a number of them will surround a bystander, making menacing feints and hurling invective until the victim is reduced to tears. Vampire-like, they always disappear at the light of day. Another form of goblin in Fuentes is the all-white ghost, or carpanta, a man or women entirely swathed in heavy cloths or linens. The carpanta’s face is always covered and featureless so that the effect is one of a cipher, a shapeless, disembodied ghoul. The festival resembles the American Halloween in some ways, but these demons do not ask for treats; their only function is to attack and discomfort.

Another wild event featuring pretend goblins takes place in Acehuche in mid-winter and is known as Las Carantoñas, a word that can be translated as Ugly Faces or Ogres. According to the protagonists of this madcap festival, its object is for everyone in town to dress up in outlandish costumes, to appear on the streets looking “as fiendish as possible,” and to assume the look of fantastic evil beings or half-human ogres (Marcos Arévalo 2001: 20). Joining in enthusiastically, the entire town put on grotesque masks and homemade outfits, with an emphasis on mythical beasts they call chimeras and human metamorphs like werewolves, vampires, and minotaurs, and then rush about town marauding and pillaging. According to the townspeople, their purpose in the aggressive masquerading is to bring all the evil of the town to the surface in the most ugly form possible in order to suppurate it, expel it, and cleanse the field. All this brings us to the arch-fiend of all southern Europe, the Pentecostal dragon, called Tarasque in France and Tarasca in Spain.

As in many matters of religion, Catholic Spain shares ceremonial traits with neighboring France, one of which is a special liturgical monster. This is the famous Tarasque, the dragon-serpent of Corpus Christi and of the Feast of Pentecost, which in Catholic imagery symbolizes evil, sin, the devil, or paganism fighting against holiness. Usually represented in statuary and pictures in both countries’ art as a man-eating sea serpent or some variant of a medieval dragon complete with fire-breathing snout, it may have originated in the early Middle Ages in the Provençal town of Tarascon (population 8,000), from which it takes its name, although it may have Celtic roots and date from even earlier, pre-Christian times. The contextual legend of St. Martha, dragon-slayer, however, arose in the twelfth century in Tarascon and quickly spread to the adjoining areas of the Languedoc and over the Pyrenees to Spanish Catalonia; along with it came the image of the man-eating dragon as a metaphor for sin.

According to the ancient legends, the Tarasque was a huge amphibious beast resembling a horse in overall shape, but with a lion’s head and toothy mouth, six bear’s paws, a carapace studded with great spikes, and a viper’s tail. One imaginative local historian describes the beast as resembling “a giant armadillo” because of the humped, spiked back in many local representations (Nourri 1973: 44). It supposedly originated in Asia Minor but parked itself along the Rhône River in the south of France for a long time (perhaps favoring the climate like so many other visitors), where, aside from impeding navigation, it made a nuisance of itself by preying on local people, mainly eating virgins, as is customary for monsters. Celebrating its man-eating proclivities, representations on the town crest of Tarascon always feature a beast with wide-open mouth from which protrude the legs of a half-eaten victim.

Finally, the people could stand it no longer and sought celestial assistance. A holy woman, St. Martha, having arrived in Provence by means of a fortuitous shipwreck—incongruously, she is today the patron saint of hoteliers and restaurateurs in France—put a stop to its depredations by drenching the Tarasque with holy water just as it was devouring a man. After this holy intervention, the monster supposedly lost its ferocity and became tame, even benevolent, acting rather like a devoted pet to the saint, who lashed the now tame beast to her girdle. But the local people did not trust the transformation and killed it just to be sure (Barber and Riches 1971: 434). Although the first mentions of the Tarasque in written documents date from the mid-fourteenth century, one text dated 1497 cites the holy monk Raban Maur (ca. 776–856), who wrote that between Aries and Avignon near the banks of the Rhône there flourished countless “ferocious beasts and formidable serpents,” as well as a terrible dragon, “unbelievably long and huge; its breath is pestilential smoke, its eyes glare sulfurously, and its snout is lined with horrible sharp teeth” (cited in Nourri 1973: 52–53). Some authorities identify the latter with St. Martha’s Tarasque, so the myth may have been current as early as the eighth century.

According to local historians, the cult of the creature became an integral part of local ceremonial traditions, its death at the hands of the Tarasconnais being commemorated in rites on various religious holidays, including Corpus Christi in mid-spring, and especially during the feast of Pentecost, which takes place seven Sundays after Easter (Renard 1991: 5). Various other localities in southern France place emphasis on similar figures of “dracs” (dragons) of various kinds during fêtes and religious observances. For example, in the villages of Razilly and Samsur, not far from Tarascon, there are festivals featuring papier-mâché gueules, or snouts of dragons, while similar monster-serpents are featured on church architecture in the towns of Aix-Sainte-Marguerite, Draguignon (whose patron saint and namesake is indeed a dragon), Saint-Mitre, Bourg Saint-Andeol, and others, including the provincial capital itself, Marseilles, whose cathedral boasts a famous “drac.”

In Tarascon proper, the observation of the monster reaches its apogee under the auspices of a local foundation called the Order of the Knights of the Tarasque (l’Ordre des Chevaliers de la Tarasque) founded in 1474 by King René of Languedoc. There, using the ancient town seals as models, the people have constructed a huge mechanical effigy of the beast which is occasionally taken out for the procession during the Feast of Pentecost. Succeeding previous incarnations dating at least back to 1465, the present statue was built at various times between 1840 and 1943, the great head dating to the earliest period (Dumont 1951: 49–50). Carried aloft by sixteen male members of the Order inside the hollow body (who represent the swallowed victims) and guided along the city streets by another eight (symbolizing the city fathers), the model is over twenty feet long and is constructed of wood and metal. It has numerous moving parts, especially its snapping jaws and a large spiked tail that swivels like a boom. According to Louis Dumont (1951), a French anthropologist who studied the effigy and its cult at mid-century, major processions took place in the years 1846, 1861, 1891, and after World War II in 1946; since the latter year, the ritual continues to occur on an annual basis largely as a tourist attraction, and having lost the religious connection has been renamed the Fête de la Tarasque.

Dumont tells us that, at least in the 1946 parade, which he witnessed in person, the effect of the Tarasque effigy was to convey a sense of menace and supernatural power to bystanders. As manipulated by its carriers, its behavior along the route was consistently one of “aggression” toward onlookers as the effigy made feints and lurches toward people with its huge mouth ajar and its lethal tail flailing. The objective of the cult as a whole is to manifest the “malevolent power” of evil. The man-eating theme is apparent in the procession, as the huge beast makes as if to snatch up children in its mechanical jaws. However, despite all this pretend violence, both Dumont and other French observers have noted the keenly ambivalent attitude of the people of Tarascon toward their namesake monster. As in the myth, the beast represents infernal forces, of course, being a ruthless monster, but because of its association with the saint it also symbolizes the triumph of good over evil. So there are mixed feelings. It may be best to quote at length from Dumont’s masterly (and little known) book on this point:

In summary, if the positive (sacred) prevails over the negative (evil), both are present. As in the myth [of St. Martha], what matters is not good or evil per se, but moral ambivalence: a spiritual dualism in the form of a dialectic which tends toward the positive. The Tarasque is a figure of blessedness paradoxically through its own purifying violence, or rather, the procession of the beast exploits an ambivalent power and transforms it, through the means of symbolic violence, into an essential beneficence. (1951: 121; italics in original)

Dumont argues that it is this “contradiction of good and evil,” as he calls it, in the ritual observance and in the mix of emotions inspired, combined with the timeless appeal and mystery of monsters, that explains the survival of the Tarasque cult in southern France and northern Spain since the Middle Ages. Another observer, Jean Nourri, a Tarasconnais himself, suggests that the Tarasque had by the Renaissance attained the position of a “sacred animal” in Provence, rather like the bull in ancient Crete or the cow in India. Others have noted the “totemic” quality of the Tarasque both in the French Midi and in Spanish Catalonia (Noyes 1992: 314).

Various localities in Spain have their own totemic monsters. Berga is a town of a few thousand in Spanish Catalonia, across the Pyrenees about fifty miles due north of Barcelona. The town boasts a famous celebration like that which occurs on Saint Martha’s Day in Tarascon. The Spanish fiesta, which draws visitors from all over the region and abroad, takes place each year during the feast of Corpus Christi, usually in late May or early June, when in the Catholic calendar people celebrate the body of Christ and renounce sin symbolized by devils, demons, dragons, and other hellish effigies. The observation of Corpus Christi was instituted in 1264 by Pope Urban IV in the bull Transiturus as a way of reinvigorating faith; it was confirmed and made obligatory for Christians in 1311 by Clement V (for more on this, see Rubin 1991). From the fourteenth century on there was widespread diffusion throughout western Europe of various commemorative parades and processions, presenting allegories and masques of good triumphing over evil and representing the most solemn conjoining of civil and religious celebrations known to late medieval and Renaissance urban centers. By the seventeenth century the Reformation brought them to an end, except for this corner of southwestern Europe (Noyes 1992: 228–29).

The Berga celebration is called the Patum. Amid the prancing devils and demons, the people of Berga carry aloft a huge effigy in the shape of a monster-dragon and parade it through the streets in a kind of mock challenge to the community. The most striking characteristic of this fearsome beast is that its mouth is filled with fireworks that explode continuously during the festival. The Berga monster itself is of curious aspect: unlike the French effigy, which, as some have said, resembles a giant armadillo with a spiked carapace, this Spanish cousin combines the usual long-necked dragon shape with the overall structure of a large equine. Such curious hybrid figures in Catalan mythology are known genetically as mulassas, meaning something like monstrous mules. There are references to such fabulous fauna in Catalonia going back to the twelfth century, but the first mention of the term Tarasca in this context dates from 1790, when the Berga city fathers used the term to describe their effigy to some curious Castilian visitors (cited in Noyes 1992: 319). Still cherished today, the Berga Tarasca, locally known as the mulaguita, or more commonly the Guita (a local word for a nasty, kicking mule), is constructed of wood and other materials. It is painted dinosaur-green and has a long neck atop which is perched a saurian-like head with a long snout, giving it a certain resemblance to the Loch Ness monster (Warner 1998: 116). It has been described by a local historian as an “original monster,” a creature of infernal evil, a prime example of the enduring ritual fauna of Catalonia. Half mule, half dragon, the effigy is as tall as a three-story building. Its mouth is stuffed to the brim with firecrackers and explosives, with the effect that it spits plumes of fire and flame throughout its wanderings through the town (Armengou i Feliu 1994: 100–101).

One of the fire-breathing Guitas of the Patum celebration. Berga, Catalonia, Spain. Photo courtesy Manel Excobet/Foto Luigi, Berga.

The tradition made its way down the peninsula by the thirteenth century, the first mention of the Tarasca in a ceremonial context in the southern city of Seville, for example, dates from 1282. shortly after its reconquest from the Arabs. From there it spread to the rest of Andalusia, where, as an added fillip in some localities, the model would be mounted by a choirboy called a tarasquillo (a kind of junior tarasca), whose job it was to yelp, cavort, and snatch off the hats of bystanders (Rodríguez Becerra 2000: 158). In some other provincial capitals, such as Granada and Madrid, the tradition in the early modern period ripened into elaborate processions in which the pasteboard effigy-invoked the Dragon of the Book of Revelation and carried on its back a woman playing the role of the Whore of Babylon or some other lascivious siren of the Bible.

The Tarasca of Toledo is one of the best known in Spain. Made of wood, cane, and plaster, over twenty feet long and six feet tall, this impressive piece of sculpture carries on its back a doll with a blonde wig representing Anne Boleyn—a tradition that derives from the English queen’s innocent role in Henry XIIFs rupture with Rome, when he broke with the Chruch to divorce Catherine of Aragon and marry her. Thus she represents by default all the monstrous evils of the Reformation, associated in Spain with paganism. Combining monstrosity with a dose of misogyny, these models were often worked by pulleys and, like the French Tarasque, were customarily hyper-aggressive in attacking bystanders en route. They are wedded to basic Christian symbolism but may also have specific local meanings (Noyes 1992: 313).

By the mid-seventeenth century the monster and its entourage had become the focus of the Corpus Christi festival in all of Spain, and had become so entrenched among the rabble that clerical and civil authorities felt the celebration had gotten out of hand. Accordingly, King Charles III, in a Royal Pragmatic issued dated June 21, 1780, prohibited further use of tarascas in the Corpus or Pentecost celebrations, declaring it a pagan, frivolous entertainment that imparted too much “folkloristic atmosphere” to what should be most solemn events (Sánchez Herrero 1999: 49). As in other cases of the legal interdiction of monsters, this edict was largely ignored. Tarasca parades have only died out in major cities in Spain since the civil war, partly due to the restricted finances of municipalities. There is today some evidence of a revival in certain areas (Rodríguez Becerra 2000: 159). For example, in the town of Las Hacinas near the city of Burgos, the Tarasca has been entirely detached from Corpus Christi and any religious significance, and integrated into the local carnival in February. Made of pasteboard and wood, the Hacinas figure is a crude, huge long-necked hollow monster, manipulated by five men, that tears about the town gobbling up young women, who then must remain in its commodious belly until freed by reciting magic formulae. The Hacinas beast is famous throughout the region for its unique ability to cavort with sinuous mobility and to jump a full three feet in the air during its maraudings—an acrobatic feat of which the townspeople are duly proud.

To get some of the flavor of Corpus today in Spain with its traditional Tarasca, let us take a closer look at the Patum celebration in Berga. It was observed firsthand in 1990 by the American folklorist Dorothy Noyes and reported on by her in exquisite detail in an unpublished PhD dissertation (1992). The following is based on Noyes’s splendid work and also on vibrant descriptions by Marina Warner (1998: 114–25).

Tarasca. Toledo, Spain. Note Ann Boleyn doll on spine. Photo by Fernando Martinez Gil.

When the festival occurs, the entire town of Berga becomes a street theater and is host to throngs of local people and visitors. The name Patum itself derives from the sound of a preludial drumbeat—Pa-turn! Pa-tum!— that signals the start of the celebration and is also connected to the Catalonian term for a report or explosion, cognate to the English “petard.” Noise and flame are paramount in the Patum: every night there is a raucous fireworks display and an extended salvo of rockets and Roman candles to climax the day’s festivities. Aside from the fireworks, the feature of the Berga Patum is the emphasis on demons, devils, giants, animals, and monsters.

The festivities are akin to the medieval Carnival of Devils, in which local people would dress up as demons and other infernal figures and skirmish with the crowds during a full week of orchestrated mayhem. In Catalonia the tradition of dancing devils probably relates in a generic way to the myth of St. Michael fighting against Lucifer and his legions; in Berga the demonic aspect of the pageant seems to date from an early period, if not to the beginning of Corpus celebrations in the Middle Ages. According to local scholars, there seems to have been some modification of the ritual in the early seventeenth century; the first documentary accounts, dating from 1632 mention two devils specifically, and, interestingly, also a female devil, or diablessa (Farràs i Farràs 1986: 77). However, the latter must have caused too much controversy among the populace to become a fixture of the celebration; it was presumably a man in transvestite garb, as occurs in some other rites in southern Europe in which men cross-dress, especially in carnivals and political protests (Gilmore 1998; Sahlins 1994). So the lady demon disappeared, and after 1656 there the Berga records mention only male devils and the Archangel Michael.

According to Noyes (1992: 307–9), demons and other diabolical figures figure prominently in Catalan folk culture in a general sense, both in religious rites and in oral literature. They serve as the principal nemesis of Christianity and as symbols of sin and depravity, rather like the Moors in Castilian demonology, but also as geomantic and chthonic spirits, rather like the leprechauns of Ireland. Demonic figures also play a role in popular theater in Catalonia, from the mystery plays and morality dramas of the early modern period to the passion pageants and village shepherd’s plays of the present. In all these productions devils and ogres virtually take over the role of representing evil and the base instincts. In the Berga case, these festival demons always carried large clubs or maces, which has the same meaning in Catalan as in English; aside from looking like lethal weapons to bystanders, these maces serve as a convenient platform for the pyrotechnics that are so prominent a feature of the Corpus rituals in Catalonia. An account from 1790 says that:

Two men dressed as Devils, who

with firecrackers in their maces,

hands, horns, and tails, go jumping

to the sound of the drum, and

shooting the firecrackers, another

who does the role of St. Michael

coming out to persecute them, who

with his lance assaults them and

acts as if he is killing one

of the two Devils, (cited in Noyes 1992: 309)

In the Berga event there are various stages of aggressive deviltry, when men and demons battle it out with noisy explosives. In one event, customarily taking place on the third day of the week-long festival, townsmen disguised as devils escaped from hell—by custom all men, for women do not normally play this role—run out into the central square and set off the usual firecrackers and rockets. The bomb-throwing masqueraders are made up so as to appear of great size, which makes them more intimidating, especially to the screaming children. They put on towering papier-mâché masks in the form of ogres’ heads, and their bodies are swathed in dampened vine leaves that both heighten the wild-man effect and afford a modicum of protection from the explosives they detonate. Each of these tall devils is accompanied by an assistant called an accompanyant, who lights the fuses of the bombs. As the bombs explode and the noise and fury mount, the crowd surges forward and the entire town erupts into a wild scene of hell-raising and pandemonium. Flares shoot from the devils’ horns and grapeshot bursts out in great plumes of yellow and red smoke. The night air is lit by sparks and rent by cries and shouts. Noyes, who was allowed to participate in the chaotic event as a devil (unusual for a woman), wrote of her experience.

Inside, she recalls, you climb in darkness to the upper level of the building where the equipment is stored; there a darkened face looks over a half-door: this sinister figure represents the gatekeeper of Hell. He murmurs something to shadows behind him, and after a pregnant pause, he hands you a devil suit and a mask to put on. Guitar and drum music swells and like the others you begin to jump up and down, the throngs pressing in, Roman candles showering you with sparks, the cinders all over your hands and flying painfully inside your mask. There are torturously loud explosions near your ears; a brief instant of open space and suddenly the air is filled with so much smoke and flame than you despair of regaining either your composure or your balance. Now tottering with the tumult and the noise, you follow your accompanyant until the procession comes to an end, and then your assistant removes your mask and the lights of the village come on, bathing the scene in an eerie glow (384–85). Afterward, the figure of the Angel appears and does ritual battle with the leaping exploding demons, who finally lie down in a docile manner in defeat.

The main event, however, is probably the march of the Guitas, the Tarasca-like effigies, of which there are two. Trained men working pulleys and wires manipulate the effigies as they move toward the throngs. About twenty feet long, their long serpentine necks are topped with glossy black heads complete with rolling glass eyeballs and mouths painted scarlet and full of sharp fangs. The heads appear small seen from a distance, but as the effigies approach, they are seen to be large and menacing, and the encrypted monstrousness of their appearance—the” dragon-like teeth, the blood-red coloring of the mouth, the glassy stare of the eyes, makes them all the more terrifying. Warner provides a splendid summary of their role:

The Guitas’ manipulators rush the crowd, dipping the beasts’ heads all of a sudden on one group, sweeping furiously across it, showering the bystanders with sparks. Then they suddenly swerve and mob another section of the throng, moving at breakneck speed along the length of the front lines, the lighted firecrackers in their monsters’ jaws sputtering and hissing all the while. The crowd wears heavy cotton hats and coverings as protection of the fiery saltpeter, but the young participants want to confront the danger. Later they display the scorched and holey trophies of the encounters like battle scars. (1998: 116)

People chase after the fire-spitting figures, retreating only when the Guita turns toward them and issues a well-directed column of flame. Young people are very much in the forefront of these mock-heroic confrontations, and the Guita responds generously to the feints of youths who are holding out their hats or other garments of clothing to be burned as trophies of their acts of bravery. Like a demon-god, the monster engages in a coquettish play of advance and retreat with umbrella-wielding provocateurs who challenge its authority. Drawing back just before the climax, it celebrates its firecracker detonations with a vigorous shake of its long neck and a humping tremor across its green frame (Noyes n.d.: 3)

Meanwhile, as all this is going on, there appear in the square two pairs of giants, the famous pasteboard gigantes that are paraded in virtually all Spanish village fiestas, richly garbed and representing the battling Moors and Christians of the Middle Ages. The event is completed with the dance of the dwarves, or cabezudos, grotesque child-like figures with oversized heads, who gambol about like uncontrolled children. On the following days there are further processions and masquerades, featuring various symbolic figures representing motifs in Spanish and Catalonian history. The entire fiesta concludes with a furious fusillade of rockets, fireworks, and bombs.

* * *

Monsters and ogres perform a “natural function” everywhere they appear, as Claude Kappler says in the epigram at the beginning of this chapter, referring to their indispensable expiative and psychotherapeutic effects. In rituals like those above, and in others that occur in tribal Africa and Asia, the participants reify the monstrous as effigies and statues, turning fantasies into real things which then can be displayed publicly, manipulated by people demonized according to local norms and the aesthetic schemes of the culture, confronted and defeated by the concerted efforts of the community. The ubiquity of such cultural transformations and social processes is truly remarkable, again pointing to some deep need in the human psyche to objectify inner states as metaphors and living symbols, and thus to disavow the “bad” part of the self within, to deny complicity and find external scapegoats to blame, to exculpate through means of displacement and externalization—an existential need to defend the self from the self, a need that has always existed and will always exist. The monstrous metaphor as object becomes the critical touchstone for communal renewal and for individual redemption, the sacrificial victim, the scapegoated emissary from the unconscious. And thus the monster takes on all the power of that which is denied in the self, all that which is repressed, and is both worshipped and attacked in the smoke and flame of the eternal battle.

Extrapolating from all this, we also see a brilliant thread uniting the earliest expressions of the imagination with the most recent, attesting once again to the universality of the inner struggle. The first true documented monsters appear in Franco-Cantabrian cave art. One of these, at Pergouset, dating from at least 15,000 years ago and probably earlier, depicts a dragon-like figure with a long neck topped by the head of a horse or deer, looking very much like the present-day Tarasque of France and the Guita of Catalonia. The so-called “sorcerer” in the cave of Trois-Frères, bears a striking resemblance to the hybrid figures that cavort today in the Spanish rituals we have described: man below, ogre above, half human and half beast, part demon and part god. Perhaps its function was also similar. Possibly the weird image scrawled by the cave dwellers is a prehistoric artist’s rendition of a masquerader in some forgotten rite, a metaphorical figure representing the terror and mystery of life, a mix of “everyman” and “everybeast” who was symbolically killed by the hunters—Girard’s “mimetic victim” in the Stone Age. Likewise, the Tarasca, so beloved of the French and the Spanish and so much a part of village festivities, resembles nothing so much as the fire-breathing dragons of ancient times like the Egyptian Apophis and the Mesopotamian demon goddess Tiamat, all the “wyrms” of Anglo-Saxon and medieval literature, and the demonic extraterrestrials of contemporary cinema—a unified image that has captivated man from the dawn of civilization to the present. The only thing missing as our barbarian ancestors danced around the fire exorcizing and extolling their monsters was the Roman candles of Berga, but some incendiary homage was no doubt present in the Paleolithic imagination.