What seest thou else in the dark backward and abysm of time?

—William Shakespeare, The Tempest

Now that we have now looked at monsters in every corner of the world and seen their horrible shapes and depredations in all sorts of contexts—fantasy, mythology, oral folklore, rituals, and both primitive and modern art—what can we say about their commonalities? What do all these terrible figments have in common? And what might such convergences say about the human mind that makes up such horrors everywhere in the world and at all times in history? Let us return to our original hypotheses and see how the data support our premises.

The first attribute that stands out is great size. No matter how monsters differ otherwise, no matter where they appear, monsters are vastly, grotesquely oversized. Looming intimidatingly, they pose a special challenge. Size relates in a generic sense to all animals, not only to humans, for large size means superior strength, which translates into the power advantage in confrontations. Indeed, “monster” in most modern usages refers to anything outstandingly big, as in the retailer’s term “a monster sale.” Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary (1979 ed.) gives as a primary definition of monster anything “of enormous or extraordinary size.” Yet physical enormity is not semantically implicit in the English word, which originates from roots meaning sign or portent, so we have to consider why the mind imposes such an attribute. There are two observations that are pertinent here.

The first is what bigness (especially height) means in the eyes of the observer. Monsters are always depicted looming over small, weak, and overshadowed humans. Can we point to anything common to the human experience that makes for such a consistent and powerful distortion? Aside from the size = power equation common to all animals, there is a connection to a perspective in which everything appears oversized, great, overwhelming and dangerous. Since monsters are undoubtedly connected to childhood fancies (Beaudet 1990; Warner 1998), we may look to the psychoanalysis of childhood for some direction, for monsters are children’s alter egos, their inner selves.

Here we may turn to the work of psychiatrist Percy Cohen, who has written about size and height distinctions in childhood (1980). Cohen holds that such a view has to do with the retention of a juvenile perspective of helpless inferiority. Spatial deformations derive from the unconscious blueprint inherited from a time when the observer was indeed tiny relative to others, especially in relation to the parents, who must have seemed to scrape the skies. To express present emotions of fear, awe, and dread, such as felt by a small, weak child in a world of giants, the psyche dredges up perceptual residues of the time when such feelings of danger were experienced in pictorial terms. Cohen writes of this psychic conversion process:

All men have experienced childhood; and all children have experienced adults as more powerful, more prestigious, and more experienced than they are; all children have also experienced adults as higher than they are and have come to recognize or, at least, to suppose that greater height has much to do with greater advantage. (P. Cohen 1980: 59)

To this, of course, we must add that the same physical distortion implied by gigantism also conveys the child’s fear of the overwhelmingly large (and advantaged) adult, whose vast bulk must translate into omnipotence.

The other ingredient here concerning gigantism involves the affective ambivalence sparked by an acuity of perceptive inferiority. We have seen throughout our discussion how the great monsters of world folklore are all perceived in divided sentiments. On the one hand they are objects of terror, but because of this physical asymmetry, because they are so enormously out-sized (and in this way like the gods) and as a consequence irresistibly, super-naturally powerful, they are also objects of awe, even of reverence that borders on the religious—feelings that again can only derive from fantasies of parental omnipotence. Much like the parent to the child, of the punishing God of the Old Testament, the Qur’an, and other holy texts, the giant and mysterious power has a demonstrably bifurcated impact on the observer, conjuring up both terror and admiration, and invoking deep ambivalence toward the what the philosopher Rudolph Otto in his book The Idea of the Holy (1958: 3) has called the mysterium tremendum et fascinans, the presence of the sublime, the supernatural: the Great Terror of that which is unfathomable.

Closely related to physical immensity is an organic synecdoche: the continual visual emphasis on the colossal mouth as organ of predation and destruction. However else they are rendered in anatomical terms, monsters are depicted has having yawning, cavernous mouths brimming with fearsome teeth, fangs, or other means of predation. These anatomical assets are used to rip and tear humans, to bite and rend and devour. Thus the behemoth of Christian lore is depicted as the “chewing animal” (Williams 1996: 186), the celluloid bogeys we have examined always threaten to bite and tear, as in Jaws or Jurassic Park, and the ritual demons always attack with their mouths stretching open like pools of blood, as in the Chinese folktale. Or else the monsters swallow their victims whole, as in the case of the biblical leviathan, which in contrast to behemoth is the “swallower” in scripture (187), or in the more familiar Jonah story in which the natural, great-mouthed whale takes the place of a supernatural beast.

However it is emphasized in biblical lore, a chewing or swallowing motif finds expression in all the world’s folklores in similar tropes. For example, in Celtic mythology monster-slayer Finn McCool is swallowed by a monster of indefinite form, only to be spat out whole (Campbell 1968: 91). Among the Blackfoot Indians, the culture hero Kut-o-yis is swallowed by “a great fish,” and in other American Indian tales culture heroes are routinely swallowed by sea serpents, ogres, or giant birds of prey. Among Plains Indians such as the Crow, Pawnee, Hidatsa, Arapaho, and Wichita, the “Swallowing Monster” is the motif most frequently encountered in heroic mythology and in folktales. The Hidatsa, for example, believed in a monster of unspecified shape called only “Big Mouth,” which simply opened its maw, drew a large breath, and swallowed all the men and animals within sight (M. Carroll 1992: 300). We saw that the main, in fact defining, feature of the legaselep of Micronesia and taniwha of Polynesia is that they gobble people up, often ingesting them whole—so that the miraculous escape from the belly is possible. The theme of the enveloping, ingesting maw is found in every culture, every tradition, almost to a monotonous degree (Campbell 1968: 247).

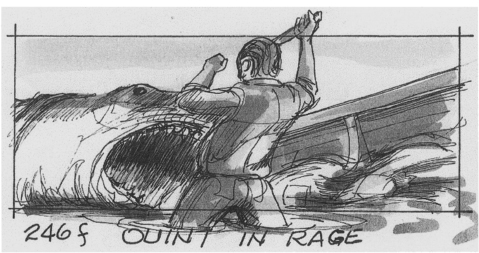

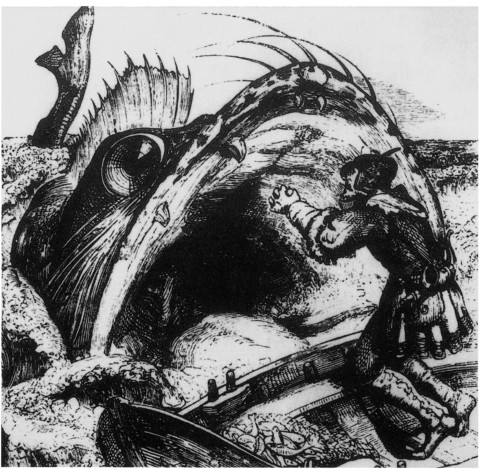

Consequently, we may conclude that this theme betrays a universal obsession with oral aggression. Monsters are always “Big Mouths.” Compare, for example, the early nineteenth-century German woodcut depicting a marine monster with the cinema image of the monster shark attacking Quint in Jaws: in almost identical scenes, imagined more than one hundred years apart, artists have focused upon the central image of the oversized mouth of the attacking creature arising from the depths and dwarfing the defenseless human victim. Comparing various monster-dragon representations from Western sources, we see that in almost every case visual emphasis is obsessively upon the mouth as weapon, along with constituent assemblages of teeth, fangs, jaws, tongue, gulping throat.

“Quint in Rage,” original storyboard by Joe Alves for the movie Jaws. Courtesy Joe Alves.

Sinner about to be devoured by water monster, illustration from nineteenth-century book.

This oral-alimentary obsession appears in most other cultures in various ways to similar effect. The Japanese serpent woman is depicted as a “ghastly eater” with protruding fangs and a gigantic mouth. The Greek Cyclops eats sailors; other monsters in Greek mythology, like the Harpies, tear and mutilate with their mouth, teeth, and jaws. The American Indian Windigo is depicted as having an enormous lipless maw dripping with blood. The pre-Columbian giants were voracious man-eaters, ingesting still-palpitating hearts just ripped from bodies. The American Thunderbird and the monster-avians of east Asia and the Pacific feed human victims to their wide-mouthed young. The Hopi kachinas are often depicted with ear-to-ear mouths, bloody fangs, and snapping jaws. Most other monsters in world cultures, no matter how envisioned, from Buddhist demons in Thailand to the jinn of the Muslim Middle East to the ogre-heads of “Monster Park” in Italy to the Devil himself in Christian eschatology, are depicted with the fierce apparatus of oral aggression. In village Spain today, as we have seen, the various ritual demons all attack children with gobbling jaws, pretending to eat them. The French Tarasque is depicted with the legs of a human victim protruding from its capacious mouth.

In most cultures, too, the monster’s mouth shows stunning diversity as a weapon. In the West, medieval dragons not only bit or swallowed men whole like the Asian and Aztec ogres, but they also spewed fire or shot lethal smoke or venom from their mouths. A prime example surviving into the present day is the Pentecost beast in Spain, which is commonly represented either as a fire-breathing dragon or as a composite of equine and dragon, as in the case of the Guita of Berga in Catalonia and elsewhere in northern Spain and southern France. In each case, the ritual statue has no anatomical weapons aside from a mouth filled with big teeth or noisy firecrackers spitting flame and smoke.

Vampire. Publicity still from Brarn Stokers Dracula (1992).

In non-Western cultures, once again, the oral cavity in such effigies appears as a deadly weapon in a remarkable variety of ways, not only by biting, chewing, and swallowing but also by emitting noise, smoke, and fire. For example, Sinhalese demons are often depicted with wide-open bloody mouths of the usual man-eating variety. But in one remarkable case the demon Kalu Yaka is often depicted with a red hibiscus flower for a mouth, out of which protrude two flaming cloth torches representing the demon’s tusks (Handelman and Kapferer 1980: 47). In Rotuma, Polynesia, the giant ogre known as “Flaming Teeth” has glowing coals for teeth. The Native American Windigo uses its mouth not only to kill and devour like a predatory animal, but also to issue thunderous screams and roars that uproot trees and cause catastrophic whirlwinds. The Cherokee utkena kills by its poisonous breath, one whiff of which is enough to fell a man (Hudson 1978: 62). The Swedish lindorm spits poisonous liquid.

Even the shape-shifters of modern fiction fit the pattern of polymorphous oral aggressiveness. Take, for example, vampires, whose mouths are often normal size in Western lore. As depicted in films and fiction, vampires always reveal themselves by oral clues: protruding canines. In addition, they destroy their victims with their mouths: draining dry, biting, devouring, dismembering, swallowing (Dundes 1998). Reviewing the literature on European vampires, psychoanalyst Richard Gottlieb notes that, despite the wide variety in the ways they are portrayed in Western folklore, they regularly destroyed with their mouths, whether by blood-sucking, flesh-eating, dismemberment, necrophilia, or simply “tearing apart” (1991: 469). The gaping, tooth-lined, flesh-tearing mouth is a universal synecdoche for monstrous predation. All this naturally brings us to the main point of all this oral depredation: cannibalism.

We see then that monsters by general agreement have rapacious mouths, which are indeed their main weapons. Monsters are almost by definition also man-eaters, using their dentition to dismember and devour humans— that is what monsters do. To fully understand the meaning of this complex and its attendant anxieties, we must delve into cannibalism and oral-aggressive fantasies, because it would appear that, whatever else it is, the monster is a cannibal fantasy.

The study of anthropophagous imagery and its social meaning starts in the psychoanalytical literature with Freud. In his early work, Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905), Freud shows an unusual interest in the subject. Writing about early psychosexual development, he introduces the concept of an oral-aggressive stage, primary to the anal, phallic, and genital sequences. Freud felt that cannibalistic urges at the oral stage were universal, but were not simply destructive, because they were also an attempt to incorporate the beloved maternal figure as part of the nascent self in order to gain possession and control over the external world and to make up for inevitable loss of the comforting object. Freud writes:

The first of these [stages] is the oral or, as it might be called, cannibalistic pre-genital sexual organization. Here sexual activity has not yet been separated from the ingestion of food; nor are opposite currents within the activity differentiated. The object of both activities is the same; the sexual aim consists in the incorporation of the object—the prototype of a process which, in the form of identification, is later to play such an important psychological part. (1905: 198)

However, like other authorities of the time, Freud also assumed that a purely aggressive cannibalistic element was present in the male sexual orientation as an innate and evolutionary aspect of the libido:

The history of human civilization shows beyond any doubt that there is an intimate connection between cruelty and the sexual instinct. . . . According to some authorities this aggressive element of the sexual instinct is in reality a relic of cannibalistic desires—that is, it is a contribution derived from the apparatus for obtaining mastery. (1905: 159)

For Freud and his followers, cannibalism is the ultimate form of sadism and indeed of human aggression itself, because it is the original form. The wish to tear with the teeth, rend, and swallow is the primary focus of all aggressive urges that follow in later life.

Freud’s follower Karl Abraham made some important contributions in a series of papers on character development (1942a, b). In his analysis, he concluded that the unexpectedly frequent cannibalistic symptomatology he encountered in clinical sessions revealed unconscious wishes to bite the mother’s breast as a revenge for infantile disappointments and frustrations during the breast-feeding stage of life (Freud’s oral stage). Like Freud, Abraham felt these aggressive wishes were universal, not just present in neurotics. However, going beyond Freud, Abraham divided the primal oral stage into two parts.

Occurring right after birth, the preliminary stage was objectless, without ambivalence, and characterized by a sucking and nutritional aim. The second stage arose once the teeth erupted and the jaw muscles developed to the point where the child could bite. This stage, spurred on by oral discomfort, was cannibalistic and ambivalent, reflecting mixed feelings toward the mother: on the one hand there are love and a wish to incorporate the maternal object, as Freud noted; on the other there is hate: the wish to bite and devour and destroy. This split in affect follows the natural development of the child toward the parental figure as the anal stage is reached and the parents become more frustrating and punishing as well as loving and nurturing.

Shortly afterward, Melanie Klein gave oral sadism a prominent and decisive role to play in her theories of the mental evolution of the child. She argued that the child undergoes a stage shortly after weaning in which its sadistic destructiveness reaches its maximal intensity, and that this stage is never fully extinguished in the mental apparatus of the adult. In later works (collected in a volume published in 1975), Klein revised the onset of this oral sadistic stage to just after birth, making it the most primary of the psychosexual periods. The contents of these infantile cannibalistic fantasies, she postulated, consist of biting the mother’s breast, tearing it apart, and sucking it dry (see Freeman and Freeman 1992: 344 for a review).

Klein seems quite aware of the role of the monster as an allegory in this fantasy. She writes that

the man-eating wolf, the fire-spewing dragon and all the evil monsters out of myths flourish and exert their unconscious influence in the phantasy of each child, and it feels itself persecuted and threatened by those evil shapes. (1975: 249)

She adds that the real objects behind those imaginary, terrifying figures are the child’s own parents, and that those dreadful shapes reflect the features of its father and mother, however distorted and fantastic the resemblance might be. The evil and distorted cannibals were not realistically arrived at by perceptions of the parents’ real behavior, but were seen as deformed by projection onto them of the child’s autonomous fantasies of oral violence against the parents, against which they want to retaliate. If these early theorists are correct, it is clear that in standard psychoanalytic treatment, oral sadism is a constituent part of normal psychosexual development, present in most or all humans, and superseded by the usual overlay of repression.

Detail from Last Judgment by Fra Angelico (ca. 1387–1455), showing the Devil devouring sinners. Alinari/Art Resource, NY

In addition, the oral-sadistic fantasies in Klein’s theory are regarded by her an her followers as derivatives of the death instinct—what Freud originally postulated as an innate aggressive drive, so that oral sadism is a mixture of libido and aggression and represents a primary—if not the primary—mode of human destructiveness. The cannibalistic fantasies direct the death instinct toward the external object—the mother’s body— and away from the ego, as a means of warding off disintegration. Also important in Klein’s theory is the emphasis on affective ambivalence, present also in Freud and Abraham, in relation to the oral-sadistic impulse. According to all three, the wish to eat the parental object and to rend the mother’s breast results not from a simple antagonism, but from mixed feelings, from a basic ambivalence, love and hate. Freud and Klein agreed that the cannibal fantasy is part destructiveness and part a desire to retain or incorporate the victim as an integral part of the self (see Gottlieb 1991). Thus identification with the victim also plays a part, as in the old adage “you are what you eat”; and the basic ambivalence is “whether to eat or be eaten” (Sagan 1974: 34). The monster narrative, in which one is attacked by a cannibal beast, can then be said to incorporate both a projection of primary aggressive impulse onto an external object, and, at the same time, a demonstration of guilt or atonement—that is, of victimization: the fantasist is both subject (eater) and object (eaten). The dual fantasy implies both a cannibalistic urge and a wish to be eaten (that is, physically punished, torn apart, mutilated).

At the same time it gives vent to infantile oral aggression, the violent monster of the imagination also embodies the sadistic parent that murderously punishes transgression with dismemberment. In this light, we may see the cannibal component of the monster, which, as an inevitable mental aspect, implies being torn asunder in order to be consumed, as a manifestation of Oedipal guilt and castration anxiety displaced onto the body. Thus the monster derives its incredible psychic power from its ability to unite different forces and opposed processes within the unconscious. One may label the monster the primary universal and multivalent symbol of the human psyche: it conflates the entire range of conflicts comprising the unconscious.

Given its power over the mind, cannibalism has been a subject of much discussion in cultural anthropology too. In the past few years there has been a major reconsideration of the phenomenon and a rather acerbic debate about its occurrence in primitive societies. In a controversial book published in 1978, anthropologist William Arens argues that alleged instances of cannibalism among primitive peoples, as reported by travelers, missionaries and the like, have been vastly exaggerated—they are the products of misinformation, ethnocentric distortion, or plain prejudice. After debunking numerous such cases cited in the anthropological literature (many truly dubious), he insists that cannibalism never in fact existed as a culturally acceptable phenomenon in any culture, although he admits that it may have occurred as a desperate (reluctant) resort to fend off starvation after catastrophes, as in the case of the Donner party. Arens’s argument here is absolute: accusations of cannibalism are always false. They are always ethnocentric inventions to demonize or dehumanize another group. This is actually not too far-fetched an idea, if one considers how often such allegations have been used to defame enemies throughout history.

Nevertheless, Arens’s passionate denial of cannibalism as an empirical fact has, in turn, been subjected to severe criticism by anthropologists who cite evidence as to its occurrence as a culturally approved phenomenon and its frequency in primitive cultures. An example is the edited volume by Paula Brown and Donald Tuzin (1983). Debunking the debunker, the contributors to this text demonstrate fairly convincing examples of anthropophagy among the aboriginal peoples of New Guinea, Oceania, and other areas. Joining the debate, other anthropologists have argued that archeo-logical and literary evidence of ritual cannibalism among such people as the Aztec is virtually incontrovertible. However, in virtually all these substantiated cases, man-eating is a highly formal ritual event, taking place as part of funeral rites with some symbolic and spiritual significance. Man-eating is virtually never a nutritional practice. No tribes have ever killed and eaten other humans for food, at least as far as we know.

Regardless who is right in this debate, my own view is that everyone involved has missed the point. The central issue is not whether cannibalism existed (it no doubt did in many pre-literate societies if only as ritual), but rather that the fantasy of cannibalism is so widespread as to be a true human “universal” (Brown and Tuzin 1983: 4). The fantasy of man-eating, in all its gory glory, not the acting out, is what counts. As psychology has taught us, people do not always act out their impulses, which nevertheless represent a mixture of wishes and fears percolating just beneath the surface. Indeed every society known to humanity shows evidence of cannibalism as a fantasy, and, indeed in many cases an obsession: either in the form of a preoccupation displaced into accusations against an enemy group (“those savages are cannibals!”) or as a label attached to despised groups within the society (as in accusations in Medieval Europe that the Jews drank the blood of Christian children)—and, of course, in the case of imaginary monsters.

If people do not practice man-eating themselves, one may be sure that they accuse others of doing it, or they invent horrible ogres who safely act out their repressed wishes, as among the Algonquians with their Windigo psychosis. There is no society in which cannibalism does not prey upon the mind as phobia. Arens’s desperate effort to deny that cannibalism ever existed is itself an example of the power of this obsession: a mania that takes its place in the repertory of the mind as the most ubiquitous nightmare, the ultimate horror, shared by all, primitive and civilized, old and young, male and female alike. It thus invokes the most intense disgust and the most ardent denials. Eh Sagan (1974) is probably right to call cannibalism the primary form of human aggression. This observation goes a long way in explaining the motif of man-eating in monster imagery.

The psychically primal status of the cannibal impulse also helps us understand oral components of monster imagery, especially the association with juvenile anxieties. No matter in what form or context they appear, the monsters we have met are wordless, speechless. Even the Frankenstein monster, although like a man in other respects, cannot articulate beyond a rudimentary level. Like others of his ilk, he roars, stammers, and shrieks. Not silent, but bellowing like Windigo, Tiamat, Vritra, Kung-kung, and “Flaming Teeth,” or hooting like the Jersey Devil or the Hopi “Monster Woman” Soyok Wuhti, monsters are emanations from the primitive pre-verbal stage of mental development. They are incapable of meaningful articulation but only use their mouths to issue the shriek or hoot of the animal or the wail and cry of the baby. They are pure affect in nonverbal form—in this they are like figures in dreams.

Monsters are thus rooted in the primary organization of the time before speech: in this primordial world there are only sounds, images, and emotions. And this wordless world is experienced through the mouth. This oral primacy that also explains the form of aggression associated with monsters: the tearing and rending, the gobbling mouths, the gnashing teeth, the cavernous maws, cannibalism itself, and the overwhelming sense of eating and being eaten as simultaneous experiences—all aspects of oral sadism, of the incorporation and destruction that are characteristic of the ambivalent infantile omnipotence, as well as infantile helplessness. Dispensing with even a modicum of disguise, the Indians in the Hudson Bay area conceive of Nulayuuiniq as a giant cannibal infant (Rose 2000: 234). In a sense, as these Eskimos have surmised, infants are cannibals: they eat and drink their mothers, both literally and figuratively. The monster is, in part, a mental remnant from that primordial stage.

In addition to all the above, we may also look to phylogeny as well as ontogeny on this score. Could it be that some of the power of this man-eating terror derives not as a product of the individual’s experience, but as a collective memory from our own infancy as a species? Could the fear of being eaten by a huge and pitiless carnivore stem from our experience with predators in the infancy of human consciousness? As the fossil evidence makes abundantly clear, Paleolithic man-eaters were gigantic, and, given the primitive level of technology at the time, surely formidable foes. The mighty cave bear (Ursus spelaeus) that infested Europe, for example, stood ten or more feet high at the shoulder (Kurtén 1976); and at the time the cave paintings were made in Europe, when men were battling these monsters for living quarters, humans were still prey to saber-toothed tigers, lions, wolves, and other large carnivores. In addition, our ancestors were much smaller at that time, the men averaging not much over five feet, the women slightly less, making the disparity in size even more terrifying (Churchill et al. 2000: 35). Other dangerous animals, even herbivores like the wooly mammoth and wooly rhinoceros, were immense in size and deadly threats as well, even if they did not eat humans. The mastodon stood twelve feet at the shoulder and the woolly rhinoceros at least six. As Caw-son (1995: 18) says, the very word monstrous “has the suggestion of size, recalling the great animals that were once everyday enemies of our ancestors.” Although this is pure speculation, it is certainly something to keep in mind when considering the deathless fascination of monsters.

Sea-serpent seen by Hans Egede in 1734, off the south coast of Greenland. From Mythical Beasts by Charles Gould (1886).

Based on the above, we can say that the monster, whatever else it symbolizes, is also a metaphor for retrogression to a previous age and time. The monster is a trip to the Shakespearean “dark backward and abysm of tune,” on a number of different levels. First, the monster, always bestial in appearance and primitive in behavior, signals a return of the primeval reptilian cerebellum, the lowest animal instincts in man. Monsters often have reptilian traits, or else, in the case of the ogres and demons of China and the Far East, simian qualities. Sometimes, as in pagan Scandinavian lore, monsters are “worms”; elsewhere they have insect or arachnid characteristics; sea monsters have fish-like or amphibian traits. This morphological convention represents a form of regression in a bioevolutionary sense: devolution to lower levels, a return to the infancy of life itself, to the primal ooze.

Second, monsters reflect primary process thinking and the oral sadism of the human neonate, which equal regression in the psychodynamic sense: the return of the individual to prior states of development. Further, in all the world’s folklore (especially among American Indians), monsters are said to be remnants of a distant geophysical past, revenants, or vestiges of the epoch before culture, when humans were helpless and vulnerable—that is, like newborns, like infants. Monsters are thus also regressive in a mythic-religious sense, predating the gods and good spirits. What all this regressive imagery suggests, of course, is that every human carries within him-or herself the entire primitive past of the species as a set of undying fantasies, and that humans are all alike in this regard. Thus the cultural displacement mechanism of the monster in folklore: a universal metaphor for the unwanted backward-leaning retrograde self.

This regressive component also might explain the consistent watery imagery in monster lore, the fact that monsters inhabit murky waters, lakes, ponds, fens, and marshes, and that they are portrayed as slimy or amphibious in appearance and behavior. Like the neonate leaving the womb in birth, monsters emerge from the deep and nurturing waters to bellow and shriek. The water that surrounds and shelters the monster symbolizes not only the amniotic fluids of the womb, but also the primal element from which all life emerged.

Next, we must consider the feature of formal hybridization in monster imagery. Perhaps none of our original propositions has been borne out as resoundingly as this one: in whatever culture, monsters are bizarre composites, made up of pieces of a reassembled reality. Promiscuously, they combine human with animal features, or mix living and dead tissue, or conflate ontological realms like the hydra and the manticore, or are amalgams of discordant parts from a variety of organisms like the Greek chimera or the Asian ogres with their ape-like traits. Monsters do indeed challenge— “reshuffle” (Harpham 1982: 5)—the very foundations of our known world. Challenging our cosmological assumptions and perceptions, monsters are cognitively as well as physically challenging.

What does this mean about the human mind? Are Douglas and Turner correct in assuming that the mind needs monsters to awaken it to unknown possibilities? Can the perceptual deformations involved in the creation of monsters have a positive mental purpose, aside from the obvious therapeutic function of giving vent to and externalizing instincts and fears? Are monsters like dreams in this regard: are they necessary for normal mental functioning?

It is clear, first of all, that Freud’s concept of dreamwork is perfectly suited to the understanding of the cognitive process of monster-making. The anatomical pieces of the monster are captured by the imagination from empirical reality, as a form of nightmare bricolage, or opportunistic scavenging by day, but imbued with powerful emotional content that informs their shape and context as dark forces. The organic components constituting the monster are symbolic manifestations of emotions displaced, or projected in visual form. When we speak of monster images conflating such feelings into a complex, animated amalgam we are employing the Freudian concept of imagistic—or structural—condensation that he proposes as an explanation for the creativity of dreams, art, and fantasies. In addition, we may see this process as occurring in a trans-temporal as well as pictorial dimension—just as Freud argued about dream images. Like dreams, the monster’s body combines everyday reality with powerful repressions emanating from past experiences and sense impressions from the unconscious; the monster always has this oneiric quality (Andriano 1999: 49). Monsters are seen vaguely, fleetingly, and are then shielded again by the darkness; indistinctly observed like dreams.

But there is also a paradoxical sense in which terrifying images, like those in bad dreams, are cognitively useful, not simply as outlets for repressed emotions, or as a way of letting off steam or literally “waking us up,” as nightmares do, but acting as salutary spurs to the imagination, waking us up to new ideas, for example. As anthropologists like Turner and Douglas have argued, our monsters indeed help us to think and to imagine; they facilitate thought and they encourage us to confront deep fears. Monsters are our guides, our entreé into the mysterious worlds that he both outside of us and within us. Therefore, although like the unknown itself, they frighten us, monsters also contribute to the development and growth of the imagination. As such they are indispensable in dealing with the challenges of life.

Many psychologists of childhood such as Denyse Beaudet (1990) and Jean Piaget (1962: 229) have surmised this important imaginative function of dream images. Piaget says that such freewheeling unconstrained mental operations as creating imaginary monsters provide Spielraum, an imaginary play-space in which young people can experiment with revolutionary ideas and images, or as Erik Erikson as put it (1972: 165), a means to infuse reality with imaginative potentiality. As Bruno Bettelheim has said, this form of creative mental play permits children to give their anxieties a “tangible form” that then can be distanced and defeated (1976:120). This projective process of course continues in adulthood, not only in dreams and fantasy, but, as we have seen, in community rituals. As Heinz Mode puts it,

It is in no small measure that they [monsters] have contributed towards bringing primeval fears into the bright light of living day, giving visible shape to creatures of the imagination, and thus bringing them out of mystical concealment and unfathomable eternity on to the brief stretch of earthly life, making them mortal. (1973: 232)

Hence there is always a non-fixed boundary between men and monsters. In the end, there can be no clear division between us and them, between civilization and bestiality. As we peer into the abyss, the abyss stares back.

Indeed, many of the most revered culture heroes have qualities that are unsettlingly similar to those of the monsters they fight. Beowulf is disturbingly like Grendel: he is outsized, aggressive, fearless, and has the same superhuman powers and limitless stamina. Like Grendel, he mutilates his vanquished foes in battle, even the females, decapitating Grendel’s mother and displaying the grisly remains as a trophy. The language of the poem makes this closeness of hero and monster unequivocal. In the Anglo-Saxon, Grendel is described as “monster,” “demon,” “fiend,” and so on, but he is also called “warrior” and “hero.” Both the monster and the monster-slayer in the original verses are called “awesome” and “awe-inspiring,” and “formidable” (Orchard 1995: 32–33). In like measure, the Yurok hero Pulekukwerek is even described as looking, as well as acting, like a monster: he is grotesquely large and sports a huge horn growing out of his buttocks—a virtual man-beast. The Indian hero Goera is also a mutilator; he chops his beaten monster-foes into tiny pieces. The mythic warriors of Polynesia, like Tamure and Pitaka, not content with simple victory, gleefully butcher and eat the ogres they kill. So in all this mutual blood and gore, who is the monster, who the victim?

Of course this ambiguity helps explain the consistent bestial imagery in monsters, as well as the human-into-beast transformations in werewolves, vampires, and the like. This mixture of human and animal is a direct consequence of a profound ambivalence shared by all people: a simultaneous terror and fascination with the beast within, the impulsive need to both deny and acknowledge that, no matter how exalted, we humans are members of the animal kingdom and heir to violent instincts. Like other animals, humans retain an atavistic side as a result of the retention of a primitive cerebellum. Coping with our dual impulses, murderous and compassionate at the same time, we make a deity of the good within us and a monster of the bad. We think in terms of polarized opposites, rather than admit the dualism and internal division, although neither side can be purified and is always contaminated by the other. Thus we decide the issue by making the monster the killer-sadist, the cannibal within which we can then cast out as an alien being. The monster remains as the reminder of the primitive nature of the psyche and its animal origins. The beast-monster is the pictorial, animated reflection of age-old human obsession with the fact of incomplete evolution.

The same may be said about the place of monsters in the physical world. As we have seen monsters emerge from a kind of metaphorical exile, from borderline places. As David White puts it (1991: 1), monsters occupy “peripheral space” in all cultural traditions. We have seen this in each and every case from the Australian bunyips to the Jersey Devil: whatever the people in a particular culture demarcate as wilderness, as noncultural space, as unexplored territory, there are monsters. As well as cognitively, in this spatial sense the monster demarcates not only between the real and the unreal, but between the permitted and the forbidden. The irruption of the monster into human affairs represents the arrival of that which is denied in the self, distanced metaphorically speaking—those traits that have been renounced and consigned “out there.” Thus we construct both the exile and the alien territory to which he belongs.

Promiscuously combining incongruent organic elements, the monster also unifies the moral opposites that comprise human comprehension. Ugly and malevolent, the monster is demonic of course, but it is also paradoxically divine: in its mystery and power, god-like and unfathomable, an object of reverence, and of admiration—even of identification—as well as of fear and loathing. “Evil is not without its attractions—symbolized by the mighty giant or dragon” (Bettelheim 1976: 9). Monstrous attributes inspire mixed emotions. Raw animal power is admirable as a means, if not an end.

Uniting both tendencies in the human heart, monsters are viewed with a sharp and undisguised ambivalence in most cultures. The Congolese Mokele-Mbembe is literally worshipped as a “beast-god” (Nugent 1993: 241) and is offered sacrifices, as is King Kong in the movie. The Babylonian Tiamat is both divine and demonic. The Windigo and the Wechuge are objects of veneration bordering on worship; the ancient chaos-monsters like Apophis are always depicted as having godlike traits or are portrayed as having some perverted kinship to the gods. The French and Spanish festival dragon is a “beloved” and revered as well as hated image (Rodriguez Beceira 2000: 158). In Tarascon the dragon even takes on the added value as a “beneficent” source of civic pride and personal identification (Dumont 1951: 121). As well as mixing cognitive categories, all these monsters unite the extremes of the moral universe, and are always imbued with what Beaudet calls a “god-demon duality” (1990: 88). It is no surprise then that in the Middle Ages, monsters were sanctified by theologians like St. Augustine, and holy persons and even God himself were sometimes represented as “monsters” (Strickland 2000: 45). The Park of Monsters in Italy is also known as the Sacred Wood. No matter how awful, the monster comes through “as a kind of god” (Campbell 1968: 222).

We have seen that imaginary monsters embody a variety of inner states, many sharply contradictory. One of these states stems from fear, a fear not only of the dangerous external world, but of the self. The monster embodies, also, the sense of guilt. For the child, the monster represents the punishing Oedipal parent, and the cannibalistic threat is a simile for castration. Yet the child also identifies with the monster, for it embodies his or her own “bad self.” Children wish to be good, that is, to conform to the ideals propagated by parents and society, but they know that they are not, that they harbor hostile, erotic, and aggressive impulses, so they invent the monster and drive it into the unconscious. Self-knowledge contradicts the self-image they strive to attain, subverts their efforts to be good, and therefore makes them, in their own eyes, a monster. What child, after being found out and punished, has not experienced the feeling of being evil and horrible, of being cast out of the human community—like a monster? As Leslie Fiedler (1978: 30) puts it, any child is bound at some time to feel “some monstrous discrepancy” between his or her impulsive nature and the role expectations of the era. The vulnerability to such self-doubt is carried into adulthood.

This fact of course explains the common interchangeability of human and monster, why in most mythologies people can so easily turn into monsters, and why most monsters retain human characteristics and the worst of human traits. Characterologically speaking, monsters are fully human: their unmotivated malice and destructiveness are human, not animal traits. My own theory of monsters stems from this “double projective mechanism,” as Kappler calls it (1980: 259). Granted, the monster embodies the raw id. But, Protean and ambivalent, the monster also represents the superego. More precisely, it represents that part of the psyche that Freud called the conscience. In various places in his work, Freud allowed as how the conscience could ally with and absorb the powerful sadism of the id in order to punish the self for imagined transgressions; in fact, this is his basic approach to sadomasochistic perversions. For Freud, the aggressive energy appropriated by the superego to punish the ego has roots “deep within the id” (Brenner 1955: 131).

I think this standard psychoanalytic formulation can be taken further. The data above show that the monster is both a powerful universal symbol and the product of a compulsive fascination that can be explained only in its own terms. The monster’s unequaled hold over the human mind requires an explanation that acknowledges the autonomy of the mental processes involved and, as we suggested earlier, points to the existence of a fourth component in the psyche. Like the ego and superego, this supernumerary agency, which I will call in the absence of any existing term the “super-id,” is a spin-off from prior stages of development, but it unites the extremes of the mental apparatus from which it has emerged, taking on a life of its own. Energized by the unbridled power of id, infused with guilt, morally empowered by masochistic identification, the monster unites, as does no other single trope, metaphor, or symbol, the totality of the psyche in all its grotesqueness, contradictoriness, whimsey, and dynamism. The monster is the super-id.

The power of monsters is their ability to fuse opposites, to merge contraries, to subvert rules, to overthrow cognitive barriers, moral distinctions, and ontological categories. Monsters overcome the barrier of time itself. Uniting past and present, demonic and divine, guilt and conscience, predator and prey, parent and child, self and alien, our monsters are our innermost selves.