Location: Off the R103, Nottingham Road, KwaZulu-Natal Midlands Web: nottsbrewery.co.za Tel: 033 266 6728 Amenities: Pub, restaurant, tasting room, accommodation, off-sales

Some of South Africa’s breweries have restaurants, some have pubs, but there are precious few where you can eat, drink and sleep without ever leaving the grounds. Nottingham Road Brewery is one of those few and it is very precious indeed. Founded in 1996, the brewery sits in the grounds of the Rawdon’s Hotel, along the popular Midlands Meander tourism route. The often misty weather marries perfectly with the British-style beers served and the quaint and cosy pub in which you can enjoy them.

“It seemed like a place that needed to have draught beer,” says Peter Dean, son-in-law of the hotel’s owner. Originally from Australia, Peter moved to Nottingham Road in 1993 and, having seen the rise of microbrewed beer in his homeland, he soon suggested installing a brewery in the hotel. It started modestly, with a 30-litre homebrew set up in the basement. With Trevor Morgan, a retired SAB brewer as a mentor, Peter learnt to brew on a spectacularly small scale, grinding malt in a coffee roaster when he graduated from extract to all-grain. “Halfway through our first brew there was a storm and we lost power,” Peter says, remembering that they had to dump that first brew and keep people waiting a little longer to taste the beers. But once a test batch hit the taps of the hotel’s bar it was obvious that the brewery would take off. In 1996, with Trevor at the helm, one of South Africa’s earliest and longest-standing microbreweries was born.

Deon Tegg was hired to manage the brewery in 2002 and took over as brewer in 2007, though his original foray into brewing, much like Peter’s, was far from successful. “In my first month we threw away 3 000 litres,” he admits candidly. “And in my second month we threw away 15 000 litres and shut the brewery for two weeks!” He recalls that beer – or an excess of it – was actually the cause of one 7 000-litre sour brew destined for the drain. After a particularly, let’s say enjoyable Christmas party, Deon swore off beer for a while – not an ideal course of action for a brewer. “For the next month I didn’t taste the beers and I didn’t realise that the entire batch had been contaminated with wild yeast.” His extreme honesty and openness – something you’ll find over and over in the brewing world – continues with a comment that many wannabe brewers should always keep in mind. “Learning to make beer is easy,” he says. “Learning how to clean up is the difficult bit!”

Luckily, Deon’s brews improved and after four years heading up the brew house he trained a new brewer, Thokozani Sithole, and took on the role of brewery manager. Thokozani had a grounding in booze production thanks to a winemaking and distilling stint at nearby Born in Africa, though it was his position at the brewery that led to a not-so-curious rise in the number of friends he has. “Some of my friends have come to taste the beer and they loved it, especially the porter,” he says. His personal favourite is the Whistling Weasel Pale Ale, perhaps in part because the beer’s alliterative name has become his own nickname at work. “They say I look like a weasel because of my small head!” he grins, whistling as he gets back to his brew.

Nottingham Road’s quirkily named beers are a constant talking point for those who come to taste and drink here, but no one seems to remember how the names were thought up. “I still think the owners were all sitting in the pub and had had quite a few beers when they came up with the names,” says Deon. “And I’m sticking to that!”

Do I need to tilt the glass when I pour beer, even if it’s from a bottle or someone else’s glass?

“This answer can change from keg to keg, but generally yes – you should always tilt the glass, at least at the start. Begin with a very small tilt, then after 100 ml you can see if you need to tilt more or not. If there is little or no foam keep glass straight, if there’s lots of foam then tilt. DO NOT let the glass or beer touch the pouring nozzle or bottle.”

TIDDLY TOAD LIGHT LAGER (3% ABV)

There are mild malt aromas on this not-too-fizzy lager. A dry, bitter finish makes it an easy-sipping session beer.

WHISTLING WEASEL PALE ALE (4.5% ABV)

Nottingham Road’s flagship beer has a mild hop aroma and a hint of toffee on the nose. It’s a smooth pint with light fruity flavours.

PYE-EYED POSSUM PILSNER (4.6% ABV)

A pale straw-coloured beer with a mild hop character. Bitter but not too much so, it’s an incredibly drinkable pint.

PICKLED PIG PORTER (4.8% ABV)

Mild aromas of caramelised sugar, toffee and smoke emerge from this chocolate-brown beer. True to style, it’s a little lighter bodied than a stout, with rich toffee tones.

One story that everyone does remember is how the pig came to be more than just another beer label, becoming the emblem and mascot for the brewery. “Rawdon’s had a black pig that was very cute when it was little and people used to feed it,” reveals Deon. “Eventually its snout was level with the tables and we had to warn people to be careful because he might steal food from their plates.” Notties’ “Beware the Pig” slogan is now emblazoned on T-shirts and other memorabilia sold in the brewery shop, while the truck that Deon drives to festivals is easily recognised for its “Pig Rig” motif.

The Pig Rig is becoming more famous as the number of festivals balloons, though Deon admits that Notties’ fame and history doesn’t always go in their favour. “At the Clarens Craft Beer Festival everyone kept walking past me – they’ve tasted our beers and they wanted to taste something new. I now know exactly what SAB feel like!” he says. Having said that, one of the brewery’s main goals now is to distribute their beers further afield, though first they’re looking at ways to prolong the shelf life of the unfiltered and unpasteurised beer. Plans are afoot to use an all-natural, locally found preservative to up the shelf life from six weeks. If successful it will mean that after a decade and a half in the brewery business, beer lovers across the country will also have to make sure that they too “beware the pig”.

Serve with a light lager, such as Nottingham Road’s Tiddly Toad Light Lager. Chef Karel says: “The bitter taste from the beer balances well with the coconut cream and there’s nothing better than to mix those two ingredients into a take on our famous local curry.”

15 ml vegetable oil

1 small onion, halved and thinly sliced

1 stalk lemon grass, finely sliced

10 ml red Thai curry paste

4 boneless and skinless chicken breasts, cut into bite-sized pieces

5 ml brown sugar

4 lime leaves

300 ml Nottingham Road Tiddly Toad Lager

150 ml coconut milk

20 g fresh coriander

SERVES 4

Visitors can view the copper kettles where Notties beers are boiled.

Chef Karel says: “Cooking with beer is quite the challenge, especially if you cook it for too long – it can become bitter and overpower the rest of the ingredients. The pilsner has a fresh, crisp taste so you need to blend that into other flavours that don’t take long to cook.”

15 ml oil

1 onion, diced

3 cloves garlic, minced

3 dried chillies, crushed

1⁄2 chorizo, diced

1 can (400 g) chopped tomatoes

1 litre Nottingham Road Pye-Eyed Possum Pilsner

1 can (400 g) cannellini beans, rinsed and drained

1 can (400 g) butter beans, rinsed and drained

1 bunch fresh spinach

Salt and pepper

SERVES 4–6

With hearty pies, beer biltong and, of course, Notties’ four beers on tap, the pub at Rawdon’s is the ideal place to escape the Midlands’ misty weather.

Location: Cnr Dennis Shepstone and Old Howick Road, Hilton Web: rdmitchells.co.za/OldMainBrewery_9.ca Tel: 033 343 3267 Amenities: Restaurant, beer tasting

Old Main might be one of the more recent additions to the KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) brew route, but the team behind it is not new to the beer scene. Rob Mitchells – no relation to the Knysna brewery – set up the Firkin Brewery in Durban in 2006. It ran for three years, but Rob admits that the rooftop of a mall wasn’t the best spot for a brewpub. “People didn’t seem to respect a brewery within a mall,” says Rob, “although the concept was great.” So Rob, a hugely successful name in KZN’s food and beverage scene, has taken that concept and moved it to pretty Hilton, sitting in the Valley of a Thousand Hills, 100 km west of Durban.

Not only did he move the idea of the brewery, he also brought master brewer Paul Sims and assistant brewer Colin Ntshangase with him. Paul is another septuagenarian brewer who cut his teeth at SAB and has been pulled out of retirement to serve in the craft beer revolution. He supervises every brew, though you get the impression that the gungho and perpetually smiling Colin could take the reins if required. After covering the basics of brewing on a food technology course in Newcastle, Colin joined the Firkin team and has been working with Rob ever since. Having encountered a number of brewers that don’t really drink beer, I put the question to Colin – his response is an even wider grin and a pat of his not huge yet not unsubstantial belly. Colin’s jolly demeanour makes you want to linger longer at Old Main, as does the interesting eating setup. The brewery, rather than being tucked away behind closed doors, sits out in the open in the restaurant, meaning you can watch Colin and Paul at work whenever they brew. It’s a unique setup that would be a perfect setting for a food and beer pairing dinner among the fermenters – something Rob is looking into as the brewery grows.

Unusually for a brewpub, Rob allows Old Main’s trio of beers to compete directly with SAB’s products – and they’re holding their own so far. “We want to give people the choice,” says Rob. “Though, of course, we hope they’ll choose our beers. For us it’s about absolute passion for an artisanal product.” As the brewery grows, beer fans can expect to find bottled beers on sale to take away and eventually the beers will be available in some of Rob’s other establishments. But for the moment you can enjoy good beers in a cosy environment, surrounded by a group of gleeful guys clearly passionate about what they do.

Colin checks the quality of the brew.

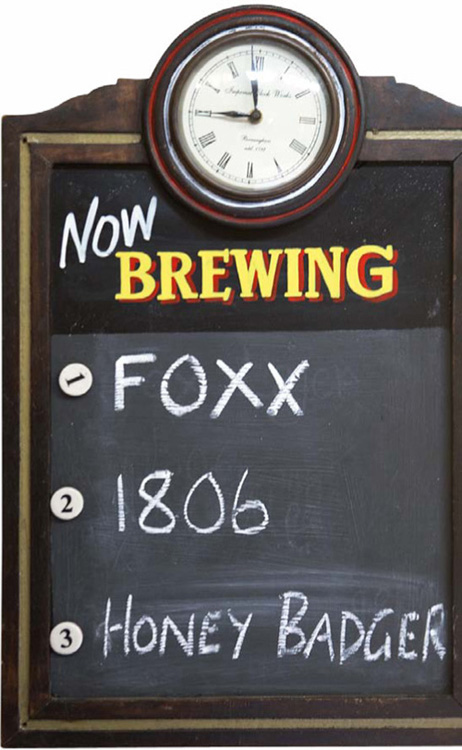

FOXX LAGER (4.9% ABV)

A long-standing favourite from the Firkin, and Old Main’s biggest seller, Foxx is an easy-drinking brew, slightly fruity and not too bitter.

1806 REAL ALE (5% ABV)

The name has no real meaning, but Colin Ntshangase’s favourite of the three is a very drinkable copper-coloured beer. Smoky, roasty and with a hint of spice, it’s a light-bodied brew suitable for year-round sipping.

HONEY BADGER IMPERIAL STOUT (5.1% ABV)

Although far from imperial, there are solid stout flavours here. A little light bodied, but filled with flavours of roasted malt and Irish coffee.

Diners can inspect Old Main’s brewhouse up-close between courses.

Location: Old Main Road, Botha’s Hill Web: porcupinequillbrewing.co.za Tel: 031 777 1566 Amenities: Beer tasting, light lunches, deli, chef school, off-sales

While all of South Africa’s brewers are enjoying riding the recent wave of beer appreciation, John Little is also helping to forge a new generation of brewers. His chef’s school is located in the picturesque Valley of a Thousand Hills region west of Durban and on the syllabus alongside knife skills, baking and sausage-making is a relatively new addition – brewing.

“The students love it,” says John. “Our second years who go over to the States to work sometimes even work at craft breweries over there when they’re off. There’s always a chance of one or two going down the brewery route and combining that with food, which would be great.” The students certainly have chance to hone their food and beer pairing skills, with gourmet dinners and other events taking place throughout the year.

Visiting the Porcupine Quill Brewery is a full-on foodie delight, with an on-site cheesery, fresh produce from the student-run delicatessen, a constant supply of baked goodies straight from the oven and, of course, a range of unique, handcrafted beers. The brewery itself is a simple system that John imported from the United Kingdom when he started up back in 2010. He didn’t follow the usual route of graduating through the homebrewing ranks before opening a commercial brewery, instead launching straight into all-grain brewing on a large-scale system. “I did a brewing course in Manchester,” says John, “but more importantly I went and worked with commercial guys that had the exact same system as mine.”

Soon enough John was back in South Africa, working on his own range of beers. First off the block was the very drinkable Kalahari Gold, followed quickly by a range of beers using ingredients from South Africa, the UK, Belgium and the USA. There are now 11 beers to choose from in three different ranges including the extreme range, Dam Wolf. These are not brews for the faint-hearted, ranging from 8–9% ABV. “I like to do my own thing with regard to the beers, hence the Dam Wolf extreme beers,” says John. His personal favourite is the Karoo Red from the flagship Quills range, though he admits that the 9% Yellow Eyes is great “if you’re looking to get fired up.” John promises exciting things to come at the brewery, including plans to age some of the higher alcohol beers in oak casks.

With 11 beers permanently available, Porcupine Quill has one of the country’s largest ranges.

The entire Quills range already has a pretty idiosyncratic flavour though, largely owing to the use of whole flower hops where most breweries opt for pelleted hops. “We want to stay as close to Mother Nature as possible,” says John. “It is more convenient to use pellet hops but flower hops make for tastier beers for sure.” His brewery is actually designed to operate only using flower hops, John explains as his faithful dog Bacardi follows us from mash tun to kettle to bottle filler. There is no kegging facility here – all of the beers are bottle-conditioned, meaning the secondary fermentation which gives beer its bubble takes place in the bottle. Because of this you can expect a touch of yeast sediment in the bottle so careful pouring is essential. “Cans are nice,” says a T-shirt in the Quills shop, adorned with cartoon boobs, “but real beer comes in a bottle.”

QUILLS KALAHARI GOLD (4.5% ABV)

A rich copper-coloured beer with a smooth, luxurious mouthfeel. Subtle flavours of brown sugar give way to a bitter taste, though not overwhelmingly. The use of American hops makes this a good companion to a Durban curry.

QUILLS NAMAQUA BLONDE ALE (4.5% ABV)

It’s dark for a blonde – like a redhead who prefers the term “strawberry blonde”! It’s a great intro to hops, with peppery spice on the nose and a short, clean finish.

QUILLS KAROO RED (5.5% ABV)

A deep russet-coloured beer with savoury aromas and a smoky, roasty flavour. Willamette hops give a faintly floral aroma.

AFRICAN MOON IMPALA LIGHT (5% ABV)

The flower hops give a unique, spicy aroma to this beer, which has flavours of caramelised sugar and a long, bitter finish.

WOLF IN SHEEP’S CLOTHING (9% ABV)

It’s the colour of toffee and has the aroma of a freshly made crème brûlée, but this beer is not as sweet as you’d imagine, especially for one so strong in alcohol. There’s a surprising roastiness that’s well balanced with hops and the typical flavours imparted from a Belgian yeast.

Also look out for Quills Black Dog Bitter and Flat Tail Porcupine Ale, the African Moon Amber Ale and Black Buck Bitter, and the Dam Wolf Howl & Cry and Yellow Eyes.

Location: B13, Kassier Road Shongweni Valley Web: shongwenibrewery.com Tel: 031 7691235 Amenities: Beer tasting, light meals, off-sales

Sometimes the brewer goes to the brewery and sometimes the brewery comes to the brewer. In the case of Brian Stewart, the latter was very much the case. Although he had been happily making beer at home for 20 years, he had no plans to turn it into a commercial enterprise. Then a local brewery came up for sale and Brian is now making beer at one of KwaZulu-Natal’s longest-standing breweries.

Shongweni Brewery was founded by British beer enthusiast Stuart Robson in 2006. A microbiologist by trade, Stuart had worked for various European breweries before setting up his own, smaller version not far from Durban. The beer range carries his surname, something that Brian is not going to change due to the label’s loyal following. “Demand still exceeds supply,” Brian grins, aware that the two brew-free months while he moved the 1 630-litre system put on further pressure from thirsty patrons. Luckily he didn’t have to move the brewery too far – in fact, the equipment only had to travel 2 km down the road to its new home on Brian’s duck farm.

Brian and Stewart were friends as well as neighbours and, after looking at the figures, in 2011 an offer was made. Following a few joint brews at its former home, the brewery moved down the road and Stuart moved back to the UK, leaving Brian to take the helm. The brewing schedule recommenced in June 2012 and luckily Brian had Johanes Mahlaba to ensure a smooth transition. Johanes had worked with Stuart Robson since the brewery’s beginnings and brings an infectiously cheery demeanour along with his knowledge of the bottle-conditioned beers. “Johanes is a huge boon,” says Brian. “He is very committed and enjoys what he’s doing.” Johanes also has plans to design his own beer, once he’s happy with the brewery’s new layout and the changes that Brian has introduced to the process.

Brian has great ideas for the brewery, with a new beer, Durban Export Pilsner, already added to the brew sheet. A strong vintage stout is also in the pipeline and Brian has developed a cherry ale, which he admits has been particularly popular with the “fairer sex”. Local restaurants are also looking to Shongweni, with Durban’s dedicated craft beer bar, Unity, being the first to make use of the brewery’s “Design-a-beer” facility, which provides restaurateurs with their own house beer. But it’s not just the local market that enjoys Shongweni’s beers – they were the first to distribute nationally and also the first to export their brews. “We definitely need to increase our fermenting capacity and conditioning capacity to keep up with demand,” says Brian, speaking of both the local market and the export orders, usually 25 000 bottles each time being sent to the UK, Canada and the USA.

The future is looking rosy for Shongweni and Brian has no lack of plans, be they beery or otherwise. Duck dishes will one day be served at the brewery and a sample of his home-distilled grappa gives the idea that a liquor collection might not be too far behind the beer range. “The whole liquor industry is of great interest and I have a lot to learn,” he says, the passion in his eyes assuring you that he won’t delay too long in studying up.

Join an utterly authentic sorghum brewing experience in Zululand with Beyond Zulu Experience Web: zuluexperience.co.za; Tel: 079 583 2623.

Many people think that the homebrewing boom in South Africa is a recent phenomenon, one that has grown up alongside the craft beer explosion. But in fact, homebrewing has been happening on a large scale throughout South Africa for thousands of years – just with a different type of beer. Figures are essentially impossible to come by, but it’s estimated that at least as much sorghum beer consumed in South Africa is made at home as that bought from commercial breweries. Unlike other beers, sorghum brews have remained virtually unchanged, never giving in to the temptations of filtration, carbonation and the like – consider it a living monument, and a useful one at that.

Called umqombothi by the Xhosa, uTshwala besi Zulu by the Zulus, doro by the Shona and joala in Tswana and Sotho cultures, there has always been more to this beer than a means to a good time. Rich in protein, vitamin B and a range of minerals, it is often referred to as a meal in a glass – well, in an earthenware pot. The beer is also still used in traditional practices, rituals and ceremonies, including coming-of-age ceremonies, weddings, funerals and when contacting the ancestors. Of course, brewing sorghum beer is also an excuse for a get-together and when Hlengiwe MaSimelane invited us to watch her brew, she knew there would follow a stream of uninvited – yet not at all unwelcome – guests the next day to sample her generations-old recipe.

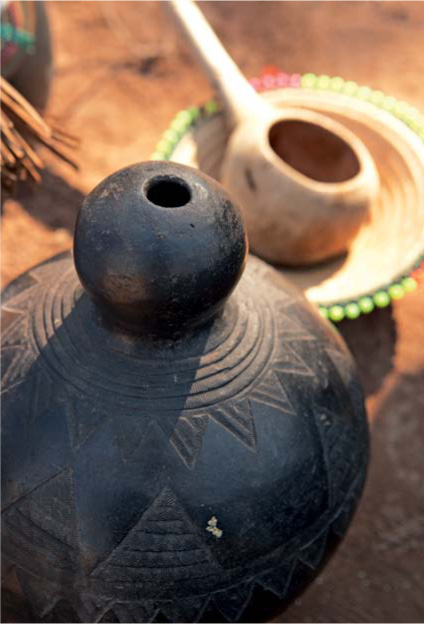

Hlengiwe’s uphiso was passed down from her grandfather.

To be fair, recipes tend not to vary too much from family to family, but they are handed down nonetheless from mother to daughter, for it is always the women who brew in traditional African culture. Hlengiwe lives in Nqolothi village in rural Zululand, a short drive from the miniscule town of Melmoth. Step one had taken place the night before – even measures of mealie meal and sorghum malt were soaked overnight to begin the fermentation process. The following morning a fire was built in the homestead’s courtyard and a hefty pot of water was slowly inching towards the boil – a lengthy process that brewers of conventional beers would likely lose their patience with.

But in rural Zululand, the pace of life is slow and while the water steadily heats up, Hlengiwe, talking through her tour-guide son Soka, shares some of the quirks and traditions that surround sorghum beer. She tells us how people will drop in unannounced when they know beer is being brewed; how pretending to have left your hat behind is a common excuse to come back for more the next day, and how she’d had to cage the generally free-roaming chickens since the aroma of the boil brings them in search of what will later become their nutritious dinner – the spent grain. There’s even time for a huge and hearty lunch of stewed meat and pap before the next part of the process occurs.

This is when the bubbling mixture from last night is gradually added to be boiled for the next hour. Although some of the equipment – like the large stick used to continually stir the mixture – is rudimentary, other items are intricately designed. The ukhamba – a communal clay drinking pot – was handmade by nearby artisans, the beaded imbenge (lid) adds a splash of colour and Hlengiwe’s uphiso – a lesser-used individual drinking vessel generally reserved for senior males – was passed down from her grandfather.

Another hour passes while Hlengiwe works methodically and in near silence, only speaking when a new part of the process emerges or a titbit of uTshwala lore occurs. She tells of vessels smaller than ukhamba, known as umancintshana. The word translates as “stingy” and if beer is served to you in such a pot it’s a sure sign that your host would like you to drink up quickly and leave. When the hour reaches its end, the mixture is decanted into an array of smaller vessels to cool, then returned to the large pot for fermentation. Unlike mainstream beer brewing, sorghum beer production doesn’t dwell on the details. Measurements are vague – a pot here; a handful there – and temperatures depend largely on the weather. Once the brew is suitably cooled – “cool enough to touch it without burning yourself” – another measure of sorghum malt is added and the mixture is placed in a cool corner of the house overnight. While specific temperature control is not essential, there are some stipulations for fermenting sorghum beer – no onions, paraffin or oranges can be placed near the gently bubbling liquid, for they all impart unwanted flavours to the finished beer.

Decanting the brew, post-boil.

Although much of the country’s sorghum beer is produced in family homes, there are commercial breweries offering pre-packaged beer. The beer is served in plastic bottles or milk-style cartons, but never in glass. As a product that continues to ferment on the shelf, each receptacle needs a vent of some sort, a hole from which the CO2 can escape. When buying pre-made sorghum beer, don’t shun the dirty bottles or cartons caked in a pinkish foam – in fact, these are the ones that are truly ready to be sipped. Although sorghum beer has changed little in generations, commercial producers are attempting to keep up with competing markets, bringing out beer flavoured with pineapple or banana to appeal to a young or female drinker.

A day later the beer is strained and ready to drink, still in an active state of fermentation. Even commercially made sorghum beers only last for a few days, though Hlengiwe is not worried about any beer being wasted. Soon some of the 140 residents of Nqolothi, spread out through the hills, will descend to sip her brew and to leave imaginary hats behind.

Sorghum beer has very little in common with its clearer, fizzier, better-known counterpart. It’s a murky, opaque brew that is pinkish-grey in colour. A sour aroma unlike any other prevails, though the beer tastes better than it smells. Low in alcohol at 2–3% ABV, there is no kick to the beer, but its gritty texture and sour flavour make it an acquired taste.

In traditional settings, men will always drink first and the genders will often drink separately, sipping in a circle from a communal pot. Make sure the beer is stirred first with the brush-like isigovuzo – if not you might find yourself sucking on a mouthful of the skin that forms when the beer is left standing.

Placing the imbenge face up means you’d like another pour of the beer; face down signifies you’ve had enough. In less traditional settings, commercial sorghum beer is often swigged straight from the carton, though the sip-and-share custom continues, leaving you with a less-than-appealing soggy carton from which to drink.