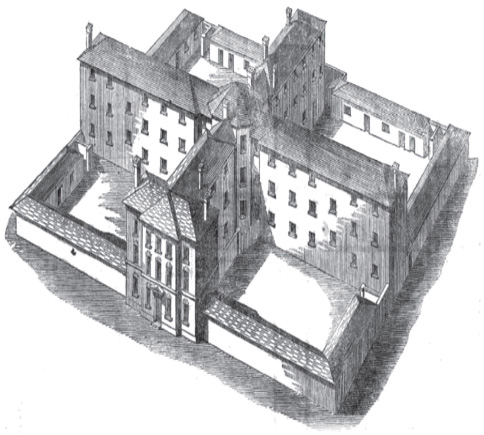

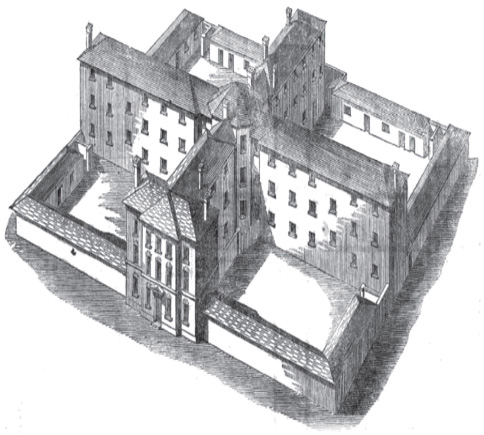

Sampson Kempthorne’s workhouse design as illustrated in Poor Law Commissioners, Annual Report, vol. 1, (1835), p. 411.

(B. 1830 DERBYSHIRE) – BROADMOOR NO.

Mary Ann Parr was described in the 1851 census as a ‘blind pauper inmate’ of Bingham’s 200-bed workhouse. That had been her home since she was a teenager, and indeed she was one of the first inmates after it opened in 1837. Mary was still living in the workhouse when the Nottinghamshire Guardian reported that:

The greatest excitement was occasioned in the village of Bingham last week by the announcement that a murder of a very revolting description had been committed in the Union Workhouse – the criminal being a female inmate called Mary Ann Parr, the victim her illegitimate female child. The unnatural mother appeared to have resolved upon destroying her unfortunate infant and from the time of its birth had refused to give it the breast, and neglected and ill-treated, and … by the wretched woman’s own confession, had wilfully murdered it … [a fellow inmate stated] She had not prepared for it, would not say who the father was … she had plenty of milk for the child, but would not let it suck. We had to put the child to her breast by force. I told her Monday last that if it did not suck it would die. She replied ‘Let it die’.

Several women from the workhouse deposed that Mary was sane, that she was warned about smothering the baby, and that she had confessed to her crime shortly afterwards. The surgeon was not convinced the child had been deliberately smothered but Mary confessed: ‘I did smother the child against my breast. I took the child to my breast at first to suckle it. I then squeezed it against my breast on purpose to take away its life, and when I saw it was dead I was frightened. I was not exactly sure it was dead till my mistress told me’.

Sampson Kempthorne’s workhouse design as illustrated in Poor Law Commissioners, Annual Report, vol. 1, (1835), p. 411.

The Derby Mercury further explained that,

The prisoner is a woman of an exceedingly low development, and her blindness gives an expression to the countenance of extreme silliness. She unites with her apparent craziness, however, a low cunning, and, when she found that the law was likely to execute justice, she made an attempt to scale the workhouse wall and escape – a design which she failed to consummate.

She was tried at Nottingham Assizes on 3 March 1853, and found guilty of the wilful murder of her ten-day-old daughter. Despite the ruthless treatment she received from the press, there was considerable sympathy at this time for women who had been forced into desperate acts through poverty, or, as seemed to be the case with Mary, through mental inadequacy. Mary was sentenced to death, but her mental condition was such that her sentence was commuted to transportation for life. She was taken from the Assize Court to Nottingham Gaol. In 1863 she was removed to Broadmoor, becoming their first ever patient (Case Number 1).

After discussion which began in the 1850s and the passing of the Criminal Lunatics Act in 1860, building began on a new secure institution near Reading in Berkshire. Broadmoor accepted its first patients (including Mary Parr) in 1863. For the first year only women were resident, but men were admitted from 1864. The original building plan of five blocks for men and one for women was completed in 1868. Over its lifetime, men would outnumber women at Broadmoor by about four to one in the Victorian period; men also served longer periods of time in the hospital, and had a greater chance of dying there. Whereas one in three women were discharged before death, only one in five men would be discharged before they died in Broadmoor.

The Broadmoor Admission register stated that Mary was:

Suicidal. Believes that everybody is her enemy. Constantly dreaming of murders. Complains of pains in her head and is most obstinate and intractable disposition. No education. Temperate. Church of England.

Nearly thirty-years later, the notes made by Dr Orange, the Superintendent of Broadmoor Hospital, noted that Mary was

Much enfeebled. Occasionally irritable, quarrelsome and excited. Present state indifferent. She is mentally unsound. Not suitable for workhouse, having been 32 years in Bethel and Broadmoor. No friends.

She died in Broadmoor at 4.55am, 31 July 1900, of chronic kidney disease. She had been kept in Broadmoor for forty-seven years.

There was a rather tragic post-script to Mary’s story. The Broadmoor files have a copy of a letter sent by her nephew. It said:

Dear Aunt, please excuse my long delay in writing I assure you it is not because I do not think of you which I often do it is so long since I heard from you that I do want to know how you are getting on an I shall be glad to hear from you as soon as possible, the years keep passing and I begin to feel that I am getting on in life ... Please write soon and think of me has your ever-loving Nephew.

By the time the letter fell through Broadmoor’s letter box, Mary had been dead for nearly two years.