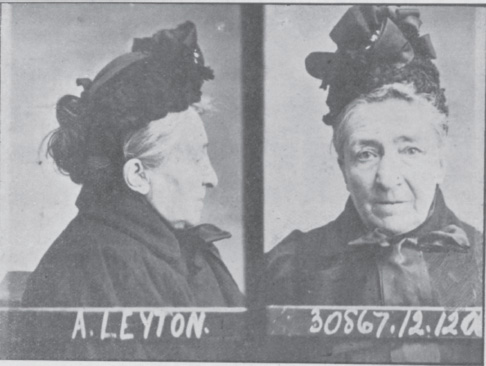

Amelia Layton. Courtesy of TNA, MEPO6/80 Prisoner 393b

(B. C.1840 LONDON) – THIRTY YEARS OF INSTITUTIONALISATION

Despite the fact that the movement in and out of different institutions over a lifetime created a long and deep documentary trail for some women, it can still be virtually impossible to know where they came from. Amelia Layton is one such case. Amelia was born in Middlesex in the late 1830s. It is not possible to know exactly when, as, at various points in her life, Amelia’s date of birth was reported as anywhere from 1833 to 1844. For most of her life, Amelia reported herself as a widow, but there is little evidence to show that she was ever married. The first records that can be attributed to our Amelia, and not one of the three other women of the same name and age as her living in London, was in 1868, when Amelia would have been around the age of 30. We know that, at that time, Amelia was admitted to the Strand Union Workhouse for two days in early November, before being discharged at her own request.

It was not unusual for individuals to resort to the workhouse in times of difficulty. This was particularly true of women, who were more vulnerable than men to personal and financial crisis (such as poor employment prospects, the loss of a family breadwinner, pre-or extra-marital pregnancy, and so on). Women like Amelia might submit themselves, as a temporary measure, to the discipline of the workhouse when funds were sparse or lodgings difficult to come by. It certainly seems like the late 1860s were uncertain times for Amelia, who returned to the workhouse again a few months later in January 1869.

Amelia Layton. Courtesy of TNA, MEPO6/80 Prisoner 393b

However, Amelia managed to stay clear of state institutions for almost the next decade, finding enough work as an artificial flower-maker to get by. It wasn’t until the summer of 1877 that Amelia returned to the workhouse, for two weeks, again being discharged at her own request in August. Amelia returned twice to the workhouse that same month, and then again in December. She returned yet another time in February 1878. Amelia’s use of the workhouse was still episodic, suggesting she was again dealing with some kind of temporary crisis. Although, unlike her first admission in the 1860s, this time the crisis seemed to last for longer, or Amelia lacked the capacity to deal with it quickly. Amelia returned to the workhouse again the following year in 1879 for a brief stay. The poverty Amelia seemed to be experiencing became more chronic than acute, and in 1881, as she sought a new way to deal with her financial problems, she turned to the dubious solution of theft. Amelia was indicted on three separate charges for stealing blankets from Mary Elsey, a pair of sheets from Sarah Vincent and a looking glass from Morris Cohen. For her trouble she was sentenced to twelve months in prison.

Spending some time in prison appears to have dissuaded Amelia from reoffending, and perhaps also put her off seeking help from other state institutions. Amelia did not return to the workhouse for almost a decade. Instead she continued to ply her trade as a flower-maker, living in a series of casual lodging houses, and unfortunately, she then turned to drink. In September 1890 she was summoned to appear before a magistrate for drunkenness but she failed to come to court, sinking instead into the shadows of the city.

Amelia’s life again began to spiral beyond her control. In January 1892 she returned to the workhouse for help, only to be discharged. In April 1892 her drinking saw her committed to Hanwell County Lunatic Asylum for a month, before she was discharged from there too. The following year she returned to the workhouse, but was only allowed to stay for two days before she was turned out. She returned again a few months later and stayed for a little over a week before being discharged again. She was back less than a month later. For the authorities, Amelia was no longer a respectable woman experiencing crisis, but an indigent burden, to be addressed and dismissed as quickly as possible.

Amelia approached the workhouse again for help in March 1894, but was turned away. That same day Amelia made a very public attempt at suicide. She walked into a Clerkenwell pub and asked for a glass of water into which she poured some ‘white precipitate powder’. Amelia then proceeded to drink the mixture in front of a crowd and claim ‘I have taken poison’, which was later confirmed by a doctor. Amelia was given over to police custody at which point she exclaimed ‘I want to die; I’ve had a lot of trouble’. She was remanded in custody but ultimately discharged by the sitting magistrate. Amelia returned to the workhouse where she stayed for almost two weeks before asking to be discharged. Amelia was clearly seeking some kind of help, for her poverty, her personal circumstances or her addiction, but failing to find it.

The following year Amelia was charged at Clerkenwell Police Court with being drunk and incapable, but once again she failed to turn up at court for her trial. A few months later she returned to the workhouse, and readmitted herself again and again – a total of three times in 1896. Amelia stayed out of trouble for almost a year, but by 1898, thirty years after her first admission, she was back to admitting herself to the workhouse on an almost monthly basis. Regular institutionalisation followed, and Amelia spent census night of 1901 at the workhouse. A few months later when she was again ‘at large’, the following newspaper report appeared:

TRYING TO DRINK HERSELF TO DEATH:

A Middle aged Widow named Amelia Leyton living at St John’s Wood-Terrace, was charged on remand with being drunk and incapable of taking care of herself at Adelaide-road – Interrogated by the magistrate the prisoner said; ‘I shall drink myself to death. I am trying to do it as much as ever I can, though I am sorry to say so.’ – She was remanded that the state of her mind might be enquired into and it was now reported that she had shown no indications of insanity and the magistrate told her to go away and keep sober.

Unfortunately, the solution to Amelia’s problems was not nearly so simple. She returned to the workhouse in August the following year, and stayed for almost four months until the beginning of 1903. The following year, after another stay in the workhouse, it was finally recognised that the current systems of court, imprisonment and the workhouse were failing to deal adequately with Amelia.

On 13 October 1904, Amelia was convicted of drunk and disorderly conduct at Marlborough Street police court. This time, an exasperated magistrate ordered Amelia to be taken to a reformatory for criminal inebriates–a secure institution, halfway between prison and hospital, in which those designated as habitual drunkards could be detained for longer periods of time than standard terms of imprisonment for drunkenness allowed. At the inebriates home, Amelia was one of almost two hundred women kept to a strict routine of chores, healthy living and sobriety. Amelia was committed to the reformatory for two years. She was released in October 1906, but in less than two months had relapsed into old habits. She was brought to the dock at Bow Street Police court, and ordered back to the reformatory for another three years.

Amelia’s case was unusual. Given that space at inebriate homes was far outweighed by the number of habitual drunkards plaguing the courts, magistrates usually only gave offenders one chance to make it through the reformatory system. If they failed to maintain sobriety, they would not normally be offered a second chance of help. Amelia though, perhaps due to advanced age (she was now in her late sixties and one of the oldest women in the reformatory), was felt to merit another opportunity. Another three years at the home did little to encourage reform in Amelia, however. When she was released in 1909, she arrived almost immediately at the workhouse, and resumed the familiar cycle of admission, discharge and problematic drinking. She was sentenced a third time to an inebriate reformatory in 1910, and remained there, in Lancashire, until 1913, when she made her way back to London.

The end of Amelia’s story was not a happy one. Although there are no more records of convictions for drunkenness, Amelia returned to the workhouse a year after arriving home. She died there in 1915, estimated to be approximately 80 years old.