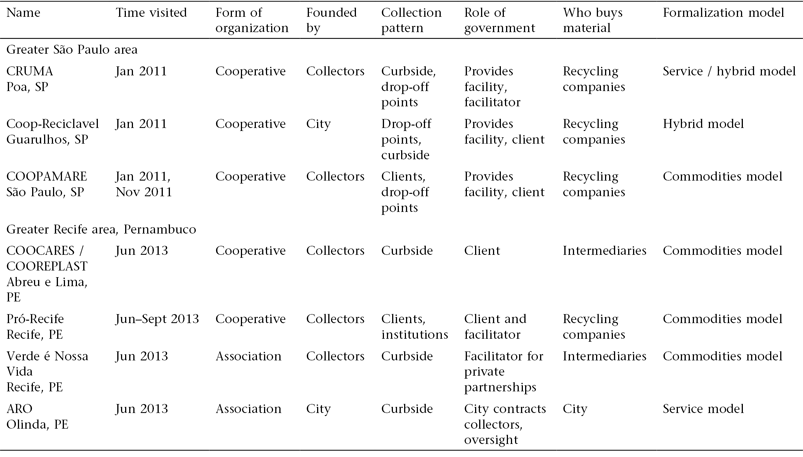

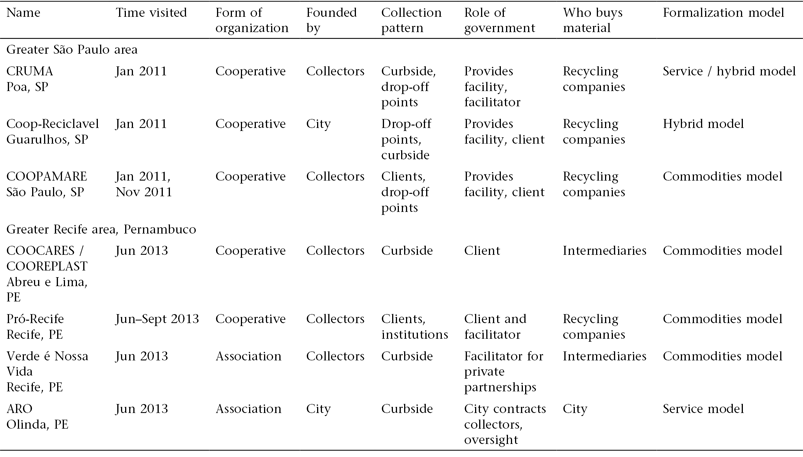

Table A.1 Overview of the investigated groups

This addendum describes the organizational structures of the recycling cooperatives we worked with when conducting the Forage Tracker experiment in São Paulo and Recife (table A.1).

Table A.1 Overview of the investigated groups

The largest metropolitan region in South America, São Paulo is home to more than fifty recycling cooperatives, about twenty of which are organized in the local network Rede Catasampa and have partnerships with the municipalities of the region. The three cooperatives we worked with are sizeable and complex organizations, well connected with local governments and the waste picker movement.

COOPAMARE is the oldest recycling cooperative in São Paulo; some of its members were cofounders of the national movement of waste pickers in 1999. COOPAMARE started as an informal association in 1986 before organizing as a cooperative in 1989 in a project initiated by the Catholic Church. It is located in the wealthy central district of Pinheiros, which offers advantages for collection but is inconvenient for most members who live in the poorer neighborhoods and endure daily commutes lasting several hours. Because the cooperative’s central location is highly attractive to private recycling companies, COOPAMARE will likely face increasing competition.

The facility, which is owned by the prefecture and houses modern equipment such as sprinkler systems, is tucked beneath a freeway viaduct in a space initially occupied by the informal pickers. Rather than servicing a whole neighborhood, COOPAMARE operates a private business through several partnerships with private and public entities. Up to three times a day, it collects from residential and business clients that include shops, apartment buildings, drop-off points, public institutions, and larger companies such as the supermarket chain Pão de Açúcar.

COOPAMARE is well equipped to implement NPSW. Companies have sponsored equipment, and NGOs are involved in educational and social projects. The cooperative receives municipal and federal grants, recently used to construct worker housing closer to the cooperative. During our fieldwork, the members generally had access to more material than they could process because of a shortage of labor, which was the main limiting factor to their business.

The cooperative uses a commodities model, selling material directly to industry. Many aspects of its operation are highly formalized. For example, a lawyer facilitates the monthly reports of processed material. However, there are many informal aspects as well. Truck routes are informally planned and documented in handwritten journals by the driver. The manual collectors working on their own do not coordinate activity with the driver. Instead, they collect, bale, and sell their own material to make more money. COOPAMARE owns two trucks, but during our site visits in November 2011, only one member had a suitable driver’s license, which highlights the dilemma that members who acquire a license can quickly find employment at higher wages elsewhere.

CRUMA, which is located in the city of Poá within the metropolitan region of São Paulo, is one of the oldest cooperatives in the city. It was founded in 1996 by the waste picker Roberto Laureano da Rocha and a few of his friends in an attempt to become independent from intermediaries. Like COOPAMARE, CRUMA was centrally involved in founding the national waste picker movement.

During our fieldwork, CRUMA consisted of forty-six members and collected eighty tons of recyclables per month from eighteen districts, which amounts to 10 percent of the total waste generated in Poá. The cooperative collects material from the curbside using a truck as a temporary collection point in a neighborhood and manual carts to visit individual households. CRUMA is also a community organization, operating a drop-off point for recyclables, running an e-waste center that accepts appliances, and serving as an educational institution for computer literacy using refurbished equipment. In response to the NPSW, the cooperative prepared a plan for extending its selective municipal collection.

The CRUMA facility is provided by the city, and the machines were acquired through various sponsorships. The truck was converted to run on vegetable fuel by the MIT research initiative Green Grease, one of several partnerships with universities (Colab MIT 2010). The cooperative works as a subcontractor for the waste management company that holds a citywide collection contract. This is a source of discontent because CRUMA members have to make income from selling material rather than by collecting.

Because CRUMA receives grants from local and national governments for various environmental and social initiatives, the formalization model can be characterized as “commodities based.” Despite grants and material support from the city, members are not compensated for collection and processing activities, and they do not earn minimum wage, making CRUMA operations not yet economically sustainable. Recently, CRUMA began to use the CataFácil software for managing its collected material and finances.

With eighty members, COOP-RECICLÁVEL is a large cooperative that collects recyclables across the entire city. Started in 2003, it was inspired by CRUMA’s model and founded by the municipality to implement a citywide curbside recycling system that processes paper, cardboard, plastics, glass, iron, aluminum, and e-waste.

The city plays a strong role in the daily operations of the cooperative, providing a well-equipped facility, two trucks, a driver, and fuel. The cooperative members who accompany the truck are responsible for sorting, separating, and baling material at the facility. COOP-RECICLÁVEL also operates voluntary collection points. Oversight, route planning, and data collection are in the hands of the municipality, which provides all necessary logistic services. The city’s central role in daily activities indicates a service model.

The organizational form of a cooperative allows the selective collection of recyclables on narrow and partially paved streets, an environment where commercial hauling is practically impossible. The structure also allows the city to address social issues and take advantage of incentives provided by inclusive solid waste policies. Formally, the cooperative maintains leadership autonomy, with the city having no formal influence in management decisions. Nevertheless, a municipal official has an office on site.

The neighborhood Fosfato in the town of Abreu e Lima, a one-hour drive from Recife, is the home of two neighboring recycling cooperatives, each ranging between twelve and nineteen members and operating under joint leadership.

COOCARES, named after Érick Soares da Silva, an influential waste picker activist who died young, was founded in 2003 as an informal association during an organized protest of waste pickers on an open dumpsite at Inhamã. COOCARES focuses on cardboard, metal, and plastic that it sells to intermediaries. COOREPLAST, which was founded by waste pickers in 2004 and became a formal cooperative in 2009, specializes in plastic. Both cooperatives went through a business incubator program of the Federal Rural University of Pernambuco and received equipment from Petrobras.

The COOREPLAST facility is a significant obstacle to the group’s development. Its area of four hundred square meters is split among several small buildings on different levels connected by narrow pathways. A machine for granulating plastic cannot currently be used due to lack of space, and PET is washed by the members in their own houses before processing. Separation takes place inside buildings, in small courtyards, and in the street. The COOCARES facility is slightly smaller but consists of one large space that is better suited to recycling. The workers, who had previously lived on the open dump, are less specialized and know how to collect and process all kinds of material, including textiles and shoes.

Together, the cooperatives operate two trucks and collect in six different neighborhoods of the town: Caetés I, Caetés II, Caetés III, Caetés Velho, Timbó, and Matinha. The drive to a collection site can sometimes take more than thirty minutes. The collection is organized in teams of six to eight collectors, using a truck and manual carts, covering about sixty streets per day. The truck serves as a temporary collection point in a central location. Teams of two or three collectors pick up material curbside and transport it to the truck using handcarts.

Surprisingly, neither cooperative collects in its own neighborhood, Fosfato, which is the territory of informal pickers who sell material to intermediaries. The national movement of waste pickers, MNCR, does not allow cooperatives to act as intermediaries that buy from informal waste pickers. The cooperative sees this regulation as counterproductive, since it could offer the informal pickers a better price for their material. Cooperative members explained that the informal pickers refuse to join the cooperative because they prefer regular hours and daily revenue to a monthly salary.

Many aspects of both cooperatives’ operations are highly informal. Despite its status of a formal cooperative, COOREPLAST works with intermediaries, who offer lower prices but are in close proximity and accept material in smaller quantities. The cooperative has to sell material as quickly as possible because it has little storage space and lacks the financial cushion needed to wait for better prices.

COOCARES, on the other hand, sells about 60 percent directly to industry due to partnerships with Coca-Cola and the PET recycling company Frompet. The cooperative also provides services such as removing caps and labels from PET bottles—a process that currently cannot be accomplished by machines. Both cooperatives also trade material that they are not equipped to process with other associations. Members confirm that they could process and sell much more material if they had more space and more workers.

Both COOCARES and COOREPLAST use accounting and data collection, document the working hours of their members, and keep books on the materials collected and sold. During a 100-day program led in 2012 by the CATA AÇAO partnership,1 both cooperatives learned bookkeeping and accounting, a practice still maintained more than one year after the project. Members take pride in their accounting skills. The books are not securely stored in the office, but placed prominently in the common room where everyone can see them. As the biggest benefit, keeping track of collected materials allows the cooperative to negotiate contracts with companies such as Frompet.

Pró-Recife is Recife’s largest cooperative, and it is a workplace for forty-one persons, mostly women. Located in the Boa Viagem district, the cooperative was founded in 2006 by a public-private partnership between the regional government, the AVINA Foundation, and the Walmart Corporation. The coop received machines, facilities, and training from this partnership.

Like COOPAMARE in São Paulo, Pró-Recife operates a private collection service with individual clients. They hold collection contracts for most public buildings and government institutions in Recife, and they provide collection services for large companies, supermarkets, and other generators of recyclable materials. Private collection creates logistic challenges, including traffic and driving restrictions, missed appointments, and a highly variable amount of material available at each site. Unpaved streets around the facility, which are regularly flooded and impassable during rains, are a serious service impediment.

E-waste is a major interest for the cooperative. Through its government contracts, it regularly receives waste equipment, but so far has been unable to make a profit from it due to the underdeveloped electronic recycling industry in Recife. A second issue stems from the reporting requirement of the NPSW, which demands that the cooperative document the source of the material before selling it at a profit. Despite its high intrinsic value, e-waste is currently less attractive than paper or PET.

Pró-Recife is one of the winners of the formalization process, representing a successful example of the commodities model. Facilitated by state and national policies, the cooperative has been able to secure many public and private contracts. By selling directly to the recycling industry, it bypasses intermediaries and receives higher prices.

Pró-Recife uses a computer for accounting and route planning. However, with the large and sparse collection area, monitoring the performance of collection and the yield per collection point is a major concern that remains to be solved. Since prices are negotiated with each client individually, better collection data could help the cooperative to increase its revenue.

O Verde é a Nossa Vida, currently five people, has a small but well-equipped and well-organized space close to Pró-Recife in the Boa Viagem district. The group has existed for thirteen years and currently provides work for up to twenty employees. The association was founded in partnership between the city and a local packaging company that, unlike other groups, provides the facility and brings up to nine tons of material per month for sorting. The group received its current space in 2005 and formally registered as an association four years later.

Because the group is an association rather than a cooperative, it is allowed to sell services but not material, which it nonetheless sells to intermediaries informally. Since the association does not own a truck, it collects from the neighborhood around the facility using manual carts, usually three times a week. About six to seven tons of material are gathered from the street per month. Additional material collected from companies, stores, and condominiums makes the grand total a relatively modest fifteen tons per month.

Each of the collectors has a collection strategy. One interview subject collects only paper, cardboard, and PET from companies. Two other waste pickers collect PET mainly from residential buildings. Since many residents do not separate recyclables, they have to pick PET out of the waste.

In terms of information management, the association sends monthly mass-balance reports to the city detailing the amount of material collected. It sees reporting as an obligation toward the city that has little significance to its day-to-day work.

Olinda is a historic city that is designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Its narrow, steep streets are not suitable for automated waste collection. Before the cooperatives were formed, three hundred waste pickers, many of them children, lived at an open dumpsite that the city has since closed.

To address the problems, the municipal sanitation department started a special project in 1998 called Projeto Meio Ambiente e Cidadania (PMAC).2 The city hired pickers from the landfill in Água Fria to collect waste in the historic town, creating the Associação dos Recicladores do Olinda (ARO). It provided a space for separation and storage where pickers could work and sell material.

In 2003–2004, the city wanted to extend the program and provide equipment. However, the pickers were not convinced about the project’s viability and kept returning to the open dump, which offered more material in close reach. The dumps were finally closed in 2007, and the NPSW of 2010 no longer allowed collectors to operate on dumpsites. At that point, the pilot program to recognize and train pickers to collect recyclables in the city gained traction (Prefeitura de Olinda 2010).

For waste management, Olinda is divided into ten areas, for which contracts to registered associations and cooperatives are provided. ARO collects recyclables and waste in the historic part of the city, with its steep and narrow roads. It educates residents about recycling and oversees the transportation, separation, and selling of material (Macedo and Furtado 2003).

Collection occurs three days a week, using a truck and vertical carts, which are better suited for the city’s steep streets. ARO also collects during big events such as the carnival in Olinda, which creates a special logistic challenge. Recyclables are sorted at the facility. Every month, sorted material is purchased by the city on a per-weight basis. The city subsidizes the price for each ton of collected recyclables and waste, amounting to double what intermediaries pay.

ARO represents a form of a service model. The city is in charge of logistics, organization, and oversight. It provides the facility and covers costs for fuel, truck maintenance, and a driver. The long-term goal is to convert the group into an independent entity that can cover its own maintenance costs. Members have not yet reached minimum wage, so this is currently not realistic.

Data collection and oversight are conducted by the city. Officials monitor the work, weigh material, study waste composition, and administer an annual survey to measure citizen satisfaction, gathering ideas for improvement. A frequent survey response is to hire more pickers and extend collection. However, the city does not know the exact income of individual collectors. Because the city has not evaluated a commercial approach, it is not clear how costs for the association would compare. However, it can be assumed that a commercial service would be significantly more expensive for the city.