THE EARLIEST SIGNS OF AN association between hedgehogs and humans are in the form of models and wall carvings from ancient Egypt (Fig. 245). They are evidence of a long familiarity with the species that may well extend back beyond any other type of physical record, even perhaps to the Stone Age. The best and earliest wall carvings that show hedgehogs are to be found on the east wall of the mastaba (a kind of tomb) of Ptahhetep and Akhethetep at Saqquara. They date from at least 2,300 BCE and are older than the pyramids. The carvings show two hedgehogs that are just visible among an assortment of antelope that were evidently hunted locally (Davis & Griffith, 1900) (Fig. 246). There is some confusion about the identity of the other animals depicted, but the hedgehogs are unmistakeable (Lydekker, 1904). One of them is shown eating a large locust, plagues of which periodically invaded Egypt and would have been eagerly devoured by the local hedgehogs. Perhaps that is why they were regarded as being of sufficient significance to warrant depiction among the larger mammals. The two animals may be representations of the long-eared desert hedgehog (Hemiechinus auritus) rather than our western European species, but they do suggest that these spiky creatures were familiar and perhaps popular animals over 4,500 years ago.

FIG 245. Models of hedgehogs occur among the domestic artefacts of ancient Egypt, often in the form of small bottles that contained perfumes or cosmetic oils – here a jar intended to contain kohl (black eye-paint) from the 6th or 7th century BCE. (© The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.)

FIG 246. Hedgehogs are shown on an ancient Egyptian wall carving created nearly 5,000 years ago. Various local animals are depicted and the hedgehogs may be the long-eared desert species rather than Erinaceus europaeus. One of the hedgehogs is clearly attacking a locust.

Although we may know what a hedgehog is, what we call it has varied over the ages. The old Anglo Saxon name was ‘il’, a contraction of the German name ‘igel’ that is still used there today. The Norman Conquest introduced the British to the hedgehog’s old French name ‘herichoun’, which evolved into ‘urchoun’, which in turn had become ‘urchin’ by 1340. Meanwhile, the mediaeval French name ‘ireçon’ became today’s ‘hérisson’ (also the name of a small village in central France where they sell hedgehog whisky and the houses have small wooden hedgehogs on their front doors!) (Fig. 247). The word ‘urchin’ is now obsolete (having been somehow transferred to scruffy little boys) and the English name ‘hedgehog’ has been the norm since the fifteenth century. Shakespeare called it by that name, but also referred to ‘hedgepigs’ and ‘urchins’ in various places. Within Britain, there appear to be many local names recorded in the literature, such as ‘furze boar’ and ‘hedgy-pig’, which are clearly derived from existing names and probably rarely used these days. The Gaelic name is ‘graineog’ and the Irish use a similar word which refers to something nasty. In Welsh, it is ‘draened or ‘draenog’, the spiny thing, and in the Cornish language it is ‘sart’. Other old European names often associate the hedgehog with pigs, to which it is not at all related.

FIG 247. A village in central France is named for the hedgehog and the local houses have hedgehog-shaped house numbers on their doors.

As discussed in Chapter 2, many people, especially in less informed times, regard spiny animals as so distinctive that they are probably closely related and there is no real need to distinguish between them. In some languages, the same word may be used to refer to both porcupines and hedgehogs, for example, despite their important zoological differences. Sometimes this makes it difficult to be certain what is being described in the old written accounts of hedgehogs and their relationship with people. As an example of this problem, Figure 248 shows an interesting early engraving by Johannes Stradanus (1523–1605). It depicts some spiny animals being captured and refers to them as ‘Echini’ in the Latin inscription. That word translates as ‘urchins’, although in technical zoological terms it refers to spiny sea urchins. But a later handwritten title on the engraving uses the French name ‘hérisson’. So what is going on here? Dogs are helping the men in their work, as well they might when searching for hedgehogs, but these could easily be captured without needing nets as depicted. There are plenty of spades and digging tools shown, apparently being used to excavate burrows, perhaps to extract nesting or hibernating hedgehogs. But the rounded face, rather than a pointed snout, and also the long spines might suggest the intended victims are porcupines, which also live in burrows. Hedgehogs were prized as food and might justify an energetic hunt for them, but I can personally vouch for the fact that porcupines are also nice to eat. Both species occur in Italy, where Stradanus worked as a professional artist for at least 25 years. So, can we be sure whether this is a hedgehog hunt or not? Anyway it’s a nice picture, but it does highlight the fact that uncertainties can be encountered even in visual representations. It is even harder to be certain how to interpret some of the details given in old translations of ancient Latin or Greek texts. This is particularly so when we read what appear to be preposterous claims for the hedgehog’s ability to cure all sorts of maladies afflicting a gullible human population.

FIG 248. This sixteenth-century engraving highlights the uncertainty involved in the interpretation of old texts. Is this a hunt for hedgehogs (as asserted) or porcupines? If we can’t be sure of even a picture, then the ambiguity of archaic words becomes even more problematic.

FOLKLORE AND LITERARY REFERENCES TO HEDGEHOGS

Aristotle promoted the idea that a hedgehog could foretell changing weather and would site the entrance of its nest according to the likely direction of the wind. Despite its improbability, I did test this tale with respect to hibernacula and found nothing to support it. Returning to the Reverend Topsel’s statements about the hedgehog in 1658 we learn that:

when the female is to bring forth her young ones and feeleth the natural pain of her delivery, she pricketh her own belly to delay and put off her misery … whereupon came the proverb (as Erasmus saith) Echinum partum differt, the Hedge-hog putteth off the littering of her young; which also applied against them which put off and defer those necessary works which God and nature hath provided them to undergo as when a poor man defereth the payment of his debt until the value and sum grow to be far more great than the principal.

Since that was a quotation from Erasmus, the philosopher and soothsayer who died in 1536, we can assume that this bit of folklore had been associated with hedgehogs for a long time. However, it is anatomically impossible for a hedgehog to poke its stomach with its own spines and baffling that such a story should have been invented and then persist for so long (Fig. 249).

Aesop is another ancient author who might be expected to write whimsically about the hedgehog, yet his fables include only one brief tale that features this species. Its leading character is a fox that is being plagued by mosquitos. The hedgehog offers some advice on an immediate line of action to reduce the misery suffered by the tormented fox, but the latter rejects the suggestion in favour of a more considered long-term solution to the problem. Aesop’s message seems to be about people who possess a broader wisdom like the fox, individuals that we might today term ‘lateral thinkers’. They are contrasted with other folk, who like the hedgehog, might automatically think the obvious and act impulsively. It is interesting that Aesop, 2,500 years ago, should be hinting that the hedgehog was an animal of rather fixed and limited behaviour compared with the fox. We would recognise that as fair comment even today.

FIG 249. It is an anatomical impossibility for a hedgehog to prick its own belly, as alleged by Edward Topsel in 1658.

The Bible is another obvious place to look for stories that might show associations between hedgehogs and people. Two species occur in the Holy Land and in Zephaniah 2:14 it says that ‘Flocks and herds will lie down there, [and] all kinds of beasts; even the owl and the hedgehog shall lodge in her capitals’. This does suggest a benign and hospitable attitude towards hedgehogs inhabiting the vicinity of buildings, but in other versions of the Bible, that passage speaks of different species. A similar confusion exists regarding mention of the hedgehog in the book of Isiah. This is because of ambiguity regarding the meaning of an old Hebrew word ‘kibbod’ or ‘quippod’ which has been rendered variously as ‘hedgehog’, ‘porcupine’ and ‘bittern’ (Cansdale, 1970). It might actually not refer to any of them. The uncertainty exists owing to differences in the translation used for the Authorised Anglican Version of the Bible and a later translation derived from Hebrew in the official Jewish Bible. The problem was analysed in detail by the Reverend J. G. Wood in his Bible Animals (Wood, 1876) (Fig. 251). He seems to have veered towards accepting that the word kibbod did refer to the hedgehog, but without firmly stating that this was his opinion. There are very few other biblical mentions of hedgehogs and they mostly refer to its spiny condition, something that it shares with the porcupine (if not the bittern!). This is another example of how difficult it is to be certain about what writers meant so long ago and in a different language.

FIG 250. The popularity of the hedgehog became so great that it began to feature on Christmas cards. Although hedgehogs do occur in the Holy Land, mentions in the Bible are few and somewhat ambiguous.

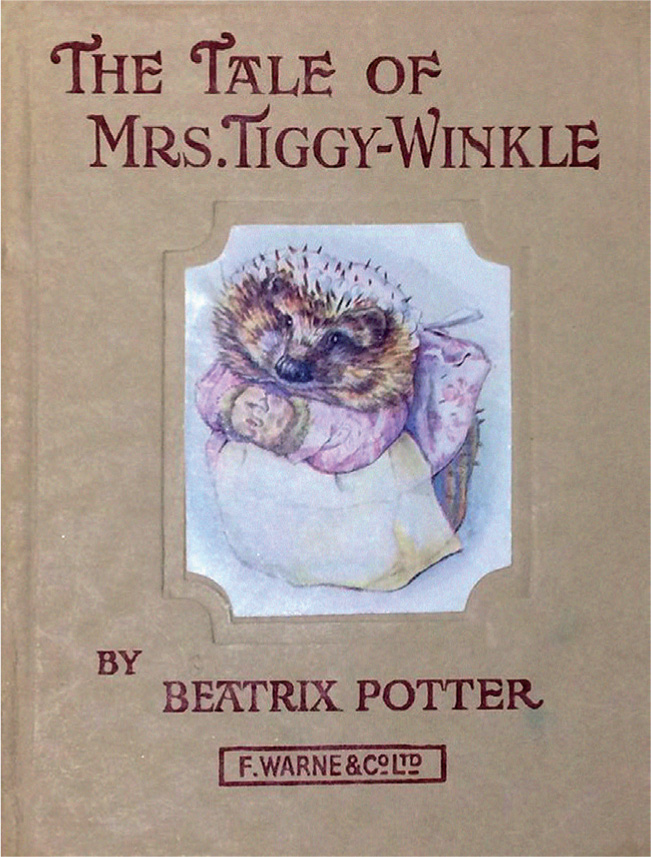

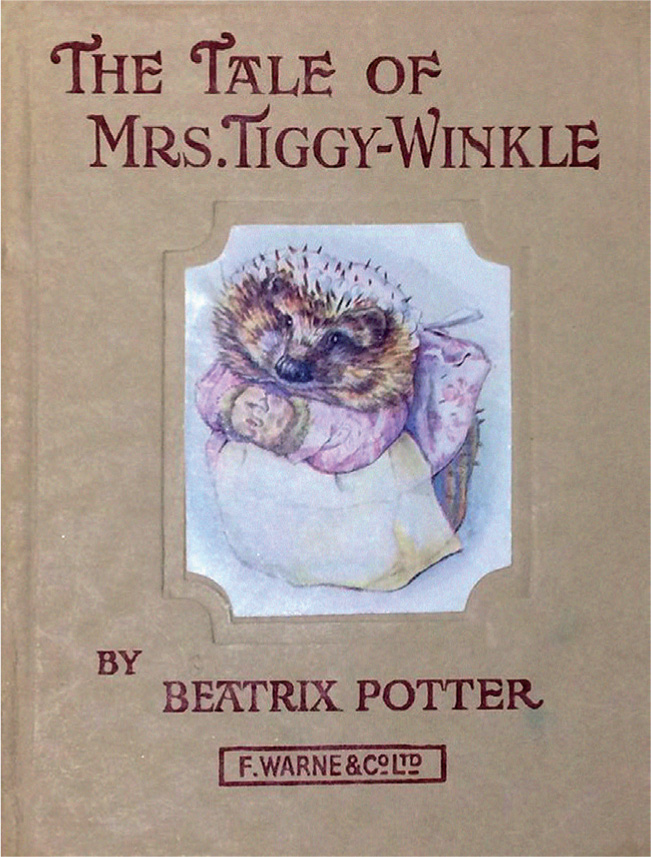

One might also look for the hedgehog in more recent literature, but it is not a very fruitful exercise. There is a passage in Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream: ‘Thorny hedgehogs be not seen; Newts and blind worms do no wrong; Come not near our fairy queen’, which some people may find insightful, but I am not one of them. The most famous (and unambiguous!) manifestation of a hedgehog in print is The Tale of Mrs Tiggy-Winkle (Potter, 1905), the story of a bustling and business-like hedgehog operating as a washerwoman in the Lake District (Fig. 252). She was created by Beatrix Potter while on holiday at Lingholm where she met Lucie Carr, the young daughter of the local vicar and inspiration for the principal human character in the book. A Scottish washerwoman, Kitty MacDonald, formed the model for the role, having worked as a domestic servant for the Potter household at one stage (Taylor et al., 1987). The tale was drafted in 1902 as a children’s book suitable for girls, centred around doing useful jobs about the house, all performed by hand without the aid of modern appliances. Thus was created an engaging and timeless story set in a tiny cottage in the Lake District fells, with young Lucie and Mrs Tiggy-Winkle delivering freshly laundered clothing in the neighbourhood.

FIG 251. The Reverend John George Wood (1827–89) was a prolific nineteenth-century author of natural history books, but despite his keen interest in animals and his ecclesiastical training, he struggled to interpret possible references to hedgehogs in different translations of the Bible.

Beatrix Potter was inspired by one of her own pet hedgehogs called Mrs. Tiggy Winkle. This is curious, as in Potter’s day ‘winkle’ was a euphemism for a boy’s penis. Anyway, she was very fond of her hedgehog and carried Tiggy with her in a cardboard box on journeys between London and the Lake District. Potter wrote to her publisher Frederick Warne:

Mrs. Tiggy as a model is comical; so long as she can go to sleep on my knee she is delighted, but if she is propped up on end for half an hour [to paint her portrait], she first begins to yawn pathetically, and then she does bite!

This is unusual, as hedgehogs rarely bite in anger, but the aggressive act does not appear to have compromised Beatrix Potter’s comely watercolour images, nor her fondness for the animal itself. She went on, ‘Nevertheless, she is a dear person; just like a very fat rather stupid little dog.’

Soon after the book’s publication, Potter’s ageing hedgehog began to show signs of failing health and she wrote to a friend:

I am sorry to say I am upset about poor Tiggy. She hasn’t seemed well the last fortnight, and has begun to be sick, and she is so thin. I am going to try some physic but I am a little afraid that the long course of unnatural diet and indoor life is beginning to tell on her.

FIG 252. Mrs Tiggy-Winkle, one of the most iconic storybook animals, first made her appearance in 1905. The whimsical tale of a Lake District washerwoman has remained in print ever since and has been translated into more than two dozen languages.

That letter was written in February, so we might suppose that the hapless creature was being kept in relatively cool surroundings, but in a state of non-hibernation. Tiggy would have been frequently disturbed and sometimes too warm to hibernate successfully, but perhaps too cold to feed and digest food adequately. This could account for its indisposition and also be a salutary lesson for many people who think they are helping hedgehogs by keeping them indoors over winter (see Chapter 6). Potter’s letter continued, ‘It is a wonder she has lasted so long. One gets very fond of a little animal. I hope she will either get well or go quickly’ (Taylor, 2012). Soon afterwards, Mrs Tiggy did indeed go quickly, (allegedly) assisted by a bottle of chloroform, and the body was buried in Potter’s London garden, now a school playground.

Thirty thousand copies of The Tale of Mrs Tiggy-Winkle were produced in late 1905, with thousands more just a few weeks later, reflecting its popular appeal. The book has remained in print ever since and is also available in Braille and as a Kindle version. It has been translated into more than two dozen languages, including Welsh and Russian. Beatrix Potter’s charming watercolours show Mrs. T. wearing clothes, including a shawl about her shoulders and a lace-trimmed bonnet, creating a lovable and homely creature whose spiny reality is obscured. The image has immense appeal and Potter was confident that her animal characters would become popular, and so it has transpired, with Mrs T. foremost among them. Her image has been reincarnated as soft toys, china mugs and Beswick porcelain figurines as a profitable form of brand extension. She has also appeared on postage stamps (Fig. 253), fancy biscuit tins, Royal Doulton china and Wedgwood plates. Two American manufacturers used Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle in their products even though hedgehogs are not native to the USA. In 1971, she became a character in a Royal Ballet film, The Tales of Beatrix Potter, and in 1993, her story formed an episode of a BBC series about Potter’s world of lovable creatures.

FIG 253. The unmistakeable image of Mrs Tiggy-Winkle on a recent British postage stamp.

Beatrix Potter died in 1943, leaving her home, ‘Hilltop’, to the National Trust (where it has remained open to visitors since 1946). Meanwhile, her animals live on. In Mrs Tiggy-Winkle, Beatrix Potter left one of the most iconic fictional creatures ever, joining Mickey Mouse, Winnie the Pooh and Rupert Bear as timeless images of childhood engagement with animals and the written word.

THE HEDGEHOG’S MEDICINAL PROPERTIES

Most of the earliest descriptions of hedgehogs included a focus on two issues, food and medical cures, as though those were really the only things that were worth knowing about these animals. Encouraged by the writings of respected authors advocating all manner of promising remedies for common ailments, hedgehogs have for centuries been captured for use as a source of supposed medicinal ingredients. In his History of Four-footed Beasts and Serpents, the Reverend Edward Topsel reviewed some of the instructions written by the ancient authorities. Aetius of Antioch, a fourth-century theologian, apparently recommended that

Ten sprigs of laurel, seven grains of pepper … the skin and ribs of a Hedge-hog, dryed and beaten cast into three cups of water and warmed, as being drunk of one that hath the Colic, and let rest, he shall be in perfect health; but with this exception that for a man it must be the membrane of a male hedgehog, and for a woman a female.

Topsel also cited other ancient authorities, including one that expounded on the properties of a hedgehog’s ashes that ‘are used by Physitians for taking down of proud swellings and for the cleansing of Ulcers and Boyles’. Apparently the power of the skin’s ashes could be enhanced by being ‘roasted with the head and afterwards beat unto powder and anointed on the head with hony, cureth Alopecia’. Topsel quoted a further seven savants who had offered their wisdom regarding the hedgehog’s utility, including Pliny, who advocated the use of hedgehog faeces mixed with vinegar and pitch to alleviate hair loss (I have not tried this yet). Salted hedgehog could be eaten by pregnant women to prevent abortions according to Marcellus, who also stated that ‘the fat of the Hedge-hog stayeth the flux of the bowels’. The hedgehog’s left eye could be made into a potion that would cause sleep if ‘infused into the ears with a quill’ and there were cures for hoarseness, warts, ‘the Bloody flux and the Cough’. The efficacy of some of these preparations could apparently be enhanced by adding a bat’s brain and milk from a dog. Topsel also referred to Dioscorides, a Greek physician in the Roman army, whose Materia Medica (written between 50 and 70 AD) was widely read for more than 1,500 years and reckoned the hedgehog to have superior curative properties compared to the porcupine.

It is easy to scoff at all this but even now, information is often afforded credibility for no better reason than that it is disseminated via the internet rather than ancient scribes. Manuka honey, colonic irrigation and the alleged benefits of alternative medicine all have prominent and numerous advocates even today in the Age of Science. In a less sophisticated time, such intricate detail as given by the ancient Greek and Roman physicians and contemporary pharmacologists must have imparted an air of authority. Who could possibly gainsay the ancient savants, quotations from whom had been offered as reputable and reliable guidance for more than a millennium? Surely the Reverend Topsel himself could be trusted too, as he was a ‘man of the cloth’ after all. Their collective words of wisdom regarding the medicinal properties of hedgehogs remained current for centuries, especially in the absence of rigorous testing. Their efficacy on humans is likely to have been minimal, likewise their impact on hedgehog populations.

To be fair, Topsel was merely quoting these historic authorities without offering critical comment himself. Perhaps he was sceptical too, but if he had felt that the inclusion of these preposterous propositions might have undermined the credibility of his book, why would he waste a significant amount of space repeating ‘facts’ that he did not believe to be true? Perhaps, like everyone else, he was not in a position to question ancient words of wisdom, simply because there was no scientifically reliable information on which to base a challenge. By an interesting irony, several of Topsel’s informants mentioned hedgehog derivatives as a cure for leprosy. It turns out that this species, along with armadillos, is very susceptible to Mycobacterium leprae, perhaps allowing it to play a part in modern experiments to create a cure for that disease after all (Klingmüller & Sobich, 1977). Meanwhile, the collection of various hedgehog species continues in North Africa and India, for example (Kumar & Nijman, 2016), evidence that belief in the animal’s curative properties is still widespread despite being unproven.

CULINARY ASPECTS OF THE HEDGEHOG

As a slow-moving, unaggressive creature that doesn’t bite, the hedgehog has always been a prime target for hungry people wanting an easy meal. One of the most widely known and widely quoted ‘facts’ about hedgehogs is that gypsies like to encase them in clay to roast in the embers of a hot fire. After a suitable interval, the clay can be broken off, pulling away the spines to leave a tasty snack. It was probably not only gypsies who ate them, but ordinary country folk too, and why not? Hedgehogs do not have strongly smelling skin glands, nor do they eat special prey whose scent might taint the flesh and impart a distasteful flavour to the meat. Hedgehogs caught in the autumn would be very fat and self-basting too, ideal for roasting over a hot fire. It is reported that ‘hyrchouns’ were served up at a feast in 1425, so their consumption was not restricted to the poor who could not afford a decent diet. Maybe they were quite widely appreciated as something of a delicacy.

When hedgehogs were on the menu, baking in clay was not the only way that they could be prepared for the table. Edward Topsel commented on this, and might be expected to offer reliable information, perhaps based upon some direct personal seventeenth-century observation rather than reliance on centuries-old historic documents. He wrote that they could be roasted on a spit after skinning, but then added inexplicably, ‘if the head be not cut off at one blow the flesh is not good’. A more reliable observer was the nineteenth-century naturalist Frank Buckland. He was always keen to pursue good natural history anecdotes and described how he had visited a gypsy woman in Oxfordshire ‘who although squalid and dirty was proud of being able to claim relationship with Black Jemmy, the King of the Gypsies’. She obligingly roasted some hedgehogs for him over a fire and told him that they were ‘nicest at Michaelmas time when they have been eating the crabs [apples] which fall from the hedges’. Some of them she said, ‘have yellow fat and some white fat and we calls ’em mutton and beef hedgehogs and very nice eating they be Sir when the fat is on ’em’ (Buckland, 1883). This observation may refer to the difference between white and brown fat (see Chapter 6).

Despite the ease of acquisition and convenience of their preparation for a meal, hedgehog remains do not appear to be common in the household middens of Stone Age settlements or among archaeological deposits accumulated during historical times in this country. It is difficult to understand why hedgehogs were seemingly infrequent food items, but just possible that the name ‘hedgepig’ and its porcine snuffling and feeding habits served to associate the animal with long-established taboos forbidding the eating of pork. There remains a strong revulsion against eating hedgehogs in Britain, but on the Continent people often ate them in countries where the spectrum of human dietary is wider than in Britain. In Germany, during the dark days of World War II, a local newspaper reported that a gypsy had been fined 10 Reichsmarks for trying to eat one without having an appropriate ration card (Hyde-Parker, 1940). In more recent times, a German chef who offered hedgehog paté at his restaurant in England swiftly removed it from his menu before he was made into paté himself by the press and local critics. It is still regularly asserted that gypsies take and bake them, although this is probably no longer commonplace, given the abundance of more appealing junk food. Nevertheless it does still go on in France, where a local newspaper reported as recently as 2014 that three men were arrested on the outskirts of Paris for collecting hedgehogs for food. Putting the words ‘hérisson’ and ‘food’ into Google will find images of a wide selection of dishes inspired by the hedgehog, some of which look delicious. However, if you also incorporate the word ‘chasse’ into the search, you can visit some French websites with graphic images of butchering hedgehogs that are too gruesome to reproduce here.

OTHER USES FOR HEDGEHOGS

Unlike many other mammals, the hedgehog’s skin is unsuitable for making leather and no use at all for furry garments. On the other hand, it does have all those spines and human ingenuity has found plenty of uses for them. When dry, the spiny skin forms a stiff bristling mat that could be stuck to the wooden door of a mediaeval house to keep scavenging dogs at bay. Nailed to a fence, it might stop vandals climbing over to raid an orchard. Fixed to the top rail of a gate, it would deter horses from leaning on it and attached to the shafts of a carriage, it could stop a horse from dozing off and leaning to one side when it was supposed to be at work. Firmly fixed to a pair of boards, two pieces of spiny skin were made into a device for combing wool or flax fibres ready for spinning.

That ingenious idea dates back to at least Roman times, when the Senate apparently became anxious enough to preserve this useful animal and its skin by passing legislation to protect it from destruction (Fairley, 1975). In the laboratory, the spines have been used as pins where tissue samples need to be held down in liquids that would corrode normal metal pins.

HEDGEHOG AS PETS

For millennia, humans have kept animals as useful or entertaining companions and pet-keeping has been fashionable among the wealthy since the Middle Ages. Monks and nuns were repeatedly forbidden to keep pets in mediaeval times. Later, with increasing national prosperity, pets became established as a normal feature of middle-class households. It became possible for ordinary people to afford to support animals that lacked any productive value and were not functional necessities like farm animals. This was especially popular in towns where real live animals were not a normal part of everyday life as they would be for country dwellers. In the nineteenth century, pet-keeping widened and hedgehogs were purchased to release about the house and in kitchens and bakeries in order to harness their expertise in controlling cockroaches, crickets and other undesirable commensals. The hedgehog’s utility was enhanced by stories of their rat-catching abilities and also because they required no special food that might otherwise have fed people. Among the notes added to his edition of The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne (White, 1883), Frank Buckland recorded that a Mr. Davy ‘has had forty hedgehogs at a time, he sold them to shopkeepers to sell again; the price, wholesale, was from eight shillings to twelve shillings per dozen’. Sales must have been brisk to be dealing in dozens.

Some pet hedgehogs will become very tame and allow themselves to be stroked without rolling up, but this is a very individual trait and others seem never to become tame at all. I knew a hedgehog once (‘Georgie’) that would come when its name was called and I have read stories about others that were similarly responsive (Fig. 254). It is reported that a Mr. Cocks once tamed a newly caught individual by drenching it with beer as it lay rolled up, stroking it whenever it uncurled. On recovering sobriety, it remained tame for the rest of its life. A story was published in The Irish Naturalist in 1899 about a hedgehog that would pull a toy cart, but on the whole, Erinaceus europaeus is not well suited to traditional forms of pet keeping in which the animal is allowed to wander freely through the house or kept in a small cage like a canary or hamster. It is evident from earlier chapters here that hedgehogs are surprisingly active animals accustomed to roaming over an area considerably larger than a football pitch. Healthy hedgehogs should not be confined to a small cage. The European species are also rather messy characters in captivity, often mixing their food and water, defaecating profusely and soiling their surroundings. They are mostly not very cuddly and can be quite smelly too. Their natural behaviour takes place after dark, not in daylight when we might want to enjoy their presence. Altogether, European hedgehogs do not make good household pets and probably do not much enjoy the experience either. It is currently not illegal to sell Erinaceus europaeus or offer them for sale in the pet trade, but few people do. Instead, there is a lot to be said for adopting hedgehogs as wild, free-ranging pets, a more satisfactory format for them and for us. Putting out supplementary food is a form of pet keeping in which the favoured animals retain their liberty and are able to live normal lives and express their normal behaviour patterns. Although it is not really pet keeping, rescuing sick and injured hedgehogs has also become a widespread activity, motivated by a desire to help and nurture wild animals, especially this particularly distinctive species. The benefits of these activities for wild hedgehogs are described in Chapter 11.

FIG 254. ‘Georgie’, a pet hedgehog that would come when it was called. It had a particular fondness for salted peanuts, not an ideal diet but such treats were offered sparingly.

On the other hand, from the early 1990s, African pygmy hedgehogs (Atelerix albiventris) became popular and widely available in the USA as ‘low maintenance pets’ and there is a lengthy instruction manual on their husbandry and welfare (Kelsey-Wood, 1995). These animals are accustomed to living and feeding in dry, semi-desert habitats and have readily adjusted to eating food pellets in captivity. Over the past 30 years, they have been captive-bred for enough generations that tameness has become the normal state. The animal is detached from its natural condition and has become a domestic species just like gerbils and golden hamsters. They have even been selectively bred to generate colour varieties (Fig. 256). They do not deliver a serious bite and can make engaging and interesting companions. These pet animals can bring about extraordinary changes in human behaviour, at least in the USA, with hedgehog conferences, special funerals and a general departure from everyday sanity (Warwick, 2008). Some states have banned their sale, and concern for the animal’s welfare has led to controls on removing any more of them from the wild.

Pygmy hedgehogs seen in the pet trade in Britain are animals bred specifically for that way of life and remain available here. They are much smaller than Erinaceus europaeus (about the size of an orange) and usually pale fawn or grey. They are a problem because they muddle the distinction between these animals and wild European hedgehogs. The press and social media both disseminate images of cute pygmy hedgehogs to illustrate stories about hedgehog conservation and ecology. Instagram and YouTube create confusion by fostering the impression that ‘hedgehogs’ are mainstream pets, when this is not the case with Erinaceus europaeus. A further problem arises if these endearing pygmy hedgehogs are no longer wanted and their owners conceive the idea of granting them liberty by releasing them into a garden or the countryside. Pygmy hedgehogs bred for generations in captivity are no better suited for life in the wild than Siamese cats or dachshund dogs. Out of doors, they will be confronted with cold and wet conditions, to which they were never adapted. They will also be required to hibernate during the winter, something that they will not have done before. Pygmy hedgehogs liberated in Britain, far from being granted their freedom, are more likely to be condemned to a drawn-out and miserable death. It is also illegal to release into the wild species that do not already occur in this country. Pet pygmy hedgehogs belong indoors and should stay there.

FIG 255. African pygmy hedgehogs (Atelerix sp.) have become common as novelty pets and adjust to captivity better than European species. This is the natural wild-type colouration.

FIG 256. African pygmy hedgehogs have been selectively bred in captivity for a sufficient number of generations to produce tame individuals and several colour varieties. They are now fully adapted to domestic life, just like hamsters and gerbils, and completely unsuited to life in the British countryside.

LEGAL PROTECTION

It was Queen Elizabeth I who enacted legislation that required destruction of hedgehogs as officially designated vermin and it was the second Queen Elizabeth who reversed its status by granting the animal its first legal protection. This is conferred by the Wildlife and Countryside Act of 1981, where the hedgehog is listed on Schedule 6, making it a ‘partially protected species’. In reality, this is actually not a lot of help due to the way that the Act is drafted. It is declared unlawful to catch hedgehogs using a snare, use it as a decoy or put out poison to kill it. Its listing on Schedule 6 also means that a hedgehog may not be shot with automatic weapons or caught by using gas, a dazzling light or mirror. Nor may anyone use explosives or a crossbow against it or chase the animals using a vehicle. Banning these activities was intended to protect other species and is all very well, but irrelevant to the hedgehog. There is no protection at all from the very real threats that are reviewed in earlier chapters of this book.

In view of the apparent decline in hedgehog numbers, in 2016 Oliver Colville MP led an energetic campaign to persuade the Government to upgrade the hedgehog’s legal status to make it a fully protected species. The campaign was backed by a public petition that gained nearly 60,000 signatures representing all 650 Parliamentary constituencies. In practice, upgrading legal protection would mean adding the hedgehog to Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act, where it would be listed as a fully protected species alongside the otter, dormouse and red squirrel. That too would probably be an empty gesture with little real effect. Amending the law in this way would prevent deliberate killing (although gamekeepers would probably be licensed to continue doing so), but the law would still not, and could not, protect hedgehogs from loss of hedgerows and green spaces, habitat fragmentation, badgers, road traffic, agricultural intensification or secondary poisoning from widespread use of rodenticides. In other words, enhanced legal protection would not help very much, if at all, to address the real causes of decline in hedgehog populations. Pressing for greater legal protection through revision of the Wildlife and Countryside Act might not be the best use of campaigning resources or Parliamentary time. On the other hand, upgrading its legal status would serve to highlight the hedgehog’s plight as a declining species and express a national desire to support this popular and inoffensive animal. In this way, full legal protection would be welcome and worth pursuing, in order to draw attention to the various issues involved which threaten our own environment and the survival of other wildlife. Full legal protection would also force developers to carry out survey work before destroying habitats. If evidence of hedgehogs was found, steps would have to be taken to mitigate the ecological damage done by building roads, houses and other major transformations of the countryside. This would be no bad thing, for hedgehogs and many other species. Although political pressures to build more housing are so great that a few hedgehogs would not be allowed to stand in the way of major developments, builders would at least be compelled to think about creating a more wildlife-friendly form of urban land. But rather than just promoting the hedgehog to become a Schedule 5 species, perhaps it would be more effective if Government were to amend planning law to make it a legal requirement in all new residential areas for fencing to be permeable to wildlife, through the inclusion of ‘Hedgehog Highways’ (Fig. 257). Further encouragement could come from creating a system of points-based awards for new urban green space as used in Sweden and Berlin, an idea that is under consideration by the Mayor of London for a new London Plan. This seeks to create a more attractive future for necessary urban development, with support for biodiversity as one of its key elements.

FIG 257. It could be made mandatory (or at least ‘good practice’) for all new fencing to incorporate a Hedgehog Highway hole to allow free movement between gardens and across a wider range of habitats, especially in suburban areas.

Meanwhile, the hedgehog’s natural defensive habits make it peculiarly vulnerable to cruel treatment, quite unlike most mammals which run away or bite back when handled. In Grantham, the fire brigade had to be called out one day to rescue a hedgehog from the roof of a house, having apparently been thrown there for amusement. Newspaper reports from elsewhere suggest that vandals may viciously kick a hedgehog about like a football or perhaps set one alight ‘just for fun’. That kind of mindless brutality was disappointingly common and it still goes on. In 2017, a Merseyside man pounded a hedgehog to death with a brick in a fit of rage after a dispute with his partner. In the same year, a gang in Cornwall doused a hedgehog with lighter fuel ready to set it ablaze. Legislation to prevent cruelty to animals did not apply to wild species, so prosecutions could not be pursued in the past, but at least that area of legal laxity has been resolved by the Wild Mammals (Protection) Act of 1996. This explicitly makes ill-treatment of wild animals an offence and the hedgehog is probably the biggest beneficiary. Two brothers aged 23 and 31 were given jail sentences in 2016 for kicking a hedgehog to death in County Durham barely a month after another hedgehog had been found impaled on a metal rod in the West Midlands. We might reasonably expect that such bestial behaviour had ceased centuries ago, but clearly it hasn’t and legal sanctions are an appropriate response. Separate legislation, creating similar levels of protection, exists for Scotland and Northern Ireland in the form of the Protection of Wild Mammals, Scotland Act, 2002, and the Welfare of Animals Act, Northern Ireland, 2011. Other recent legislation that may be helpful to hedgehogs includes the Hunting Act of 2004. This makes it illegal to use dogs to track down wild mammals. Although it was intended to stop fox hunting and the chasing of hares and deer, the Act might also be used as an additional tool to prosecute in cases where dogs had been implicated in the cruel mistreatment of hedgehogs.

But legislation aimed at specific threats, different for each species, is a scattergun approach to the bigger issue of wildlife conservation at the national and landscape level. A more strategic vision is required and after four years of lengthy consultation, an official UK Biodiversity Action Plan was formulated in 2007 as a statement of concern for more than 1,100 species and as an implied commitment by the United Kingdom to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. On the strength of the surveys described here in Chapter 10, the hedgehog was listed among the UK BAP priority species for which there was reliable evidence of decline and a clear need for conservation. The BAP process appears to have been abandoned soon afterwards and a revised list of vulnerable species was produced instead. The hedgehog is listed in Section 41 of the Natural Environment and Communities Act of 2006 as a species ‘of principal importance for the purpose of conserving biodiversity in England’. This requires that its needs must be taken into consideration by public bodies when performing their proper functions such as when they make decisions about developments that might impact on hedgehog habitats and populations. What this amounts to in practice – for example, when parks or public gardens are due for major improvements – is not easy to see. This is especially so because local authorities are unlikely to have a hedgehog advisor on the staff nor would they necessarily know if or where hedgehogs occurred locally. Presumably they could call upon ecological consultants to carry out the necessary surveys, using the methods described in the Appendix, but that costs money and is easily foregone. The immense political pressures to create thousands of new homes, often by building on greenfield sites, are also likely to sweep hedgehogs and other wildlife to one side. So this is another example of the hedgehog having gained the status of being mentioned in legislation, but probably with little real effect. We cannot rely on the law to save hedgehogs; that will only be achieved through widespread public engagement. Fortunately there are plenty of signs that people are willing to rally round and help.

At the time of writing (2017), Britain has signalled its intention to leave the European Union (EU). This will entail many significant adjustments to our legislation, but the hedgehog is not a ‘European Protected Species’ (unlike the otter and dormouse, for example) so its legal status is unlikely to change. However, withdrawal from the European Union will mean that EU Directives will no longer apply. The Government plans to enact legislation that transfers all EU agreements (thousands of them!) into UK law, for possible modification later. This could profoundly affect hedgehogs. No doubt the RSPB will see to it that full protection of birds will continue, but one of the reasons why so much effort was put into killing hedgehogs in the Uists was the fear that failure to abide by the EU Birds Directive and protect nesting waders might result in a massive fine being imposed by the European Court of Justice. If we cease to be answerable to the ECJ for lack of action, the Uist hedgehogs could benefit, although culling them has not been cost-effective and will probably not be repeated anyway. Whatever happens, any resumption of culling will not now be funded by the EU and perhaps not by anyone else either. Changes associated with the EU Habitats Directive might also affect hedgehogs. Once the protection of habitats becomes a matter of British law, with no external constraints, the Government may yield to pressures for more land to be released for housing and infrastructure development. Such changes are already being advocated by some and would be unlikely to benefit hedgehogs. However, many conservation organisations see an opportunity to develop a new strategy for managing the British countryside, in particular creating incentives for wildlife-friendly farming to replace the subsidies that currently support farmers through the Common Agricultural Policy of the EU. If that comes about, leading to less intensive farming and financial rewards for maintaining biodiversity, habitat links and ecological integrity, the hedgehog’s future prospects could be considerably improved.

Meanwhile there are lesser legal issues that continue to crop up. For example, approval has been sought for use of a new type of trap in Britain. It is marketed in New Zealand as a means of killing small mammal pests, including hedgehogs. That is obviously unacceptable here, but the manufacturers say that the traps can be set high enough off the ground to avoid hedgehog deaths. That is likely to reduce their effectiveness against stoats and rats and it is hard to believe that the traps will not be set lower ‘just to make sure’ that the intended victims do not escape being killed. Either these traps do catch hedgehogs (as claimed in New Zealand) or they don’t. Setting any kind of traps to catch hedgehogs is, and will remain, illegal. But it is easy to claim that hedgehog deaths were accidental and the intention was to catch something else like rats.

THE HEDGEHOG’S POPULARITY

Hedgehogs are rarely far from human affairs, as discussed and illustrated very fully in Hugh Warwick’s book Hedgehog (Warwick, 2014). They frequently appear in cartoons, often around the themes of prickly defence or being run over (Fig. 258). There are plenty of hedgehog jokes too, usually focused on these same topics. An exception won a prize at the Edinburgh Fringe in 2009 – ‘Hedgehogs. Why can’t they just share the hedge?’ According to the BBC, the judges had sifted through thousands of jokes to discover this one by Dan Antopolski. An early computer game, ‘Sonic the Hedgehog’, gained widespread popularity at the time and a search through the scientific literature reveals technical papers about a ‘hedgehog chromosome’, apparently named for its appearance, not its origin or effect. An extensive assortment of hedgehog-themed commercial goods has also appeared for sale, ranging from notepaper, slippers, tea towels, mugs and paperweights to less utilitarian items that include a board game and numerous ceramic ornaments (Fig. 259).

FIG 258. An example of a hedgehog image being used for a road safety campaign.

Periodically, there have been public opinion surveys to establish Britain’s most popular animals. Time and again, the otter, dolphin or badger would top the poll, even though most people had never seen any of them in the flesh. But public awareness has begun to pull the hedgehog to the fore. In 2007, the British people voted the hedgehog as the nation’s top ‘Icon of the Environment’ in a poll conducted by the Government’s Environment Agency to celebrate their tenth anniversary. It emerged victorious from 70 nominations that included the Agency’s own favourite, the salmon, as well as all the usual suspects like the otter, badger and red squirrel. BBC Wildlife magazine reported in 2013 that the hedgehog had gained 42 per cent of the votes in its own survey to find Britain’s ‘National Species’, easily beating everything else, even the badger. It topped the poll again in 2017. In another enquiry, by the Royal Society of Biology in 2016, the hedgehog gained 39 per cent of the votes as Britain’s No. 1 favourite mammal.

The hedgehog’s popularity seems perverse, given its reputation for being prickly and flea-ridden. It also lacks humanoid features (flat face, forward-facing eyes) that psychologists say make apes and monkeys so endearing. It is not a cuddly creature, yet it behaves in a very agreeable manner, pottering about our gardens eating slugs and not running away (or biting) when disturbed. It appears to be a tolerant and trusting creature, attributes that we welcome and we reciprocate. However, the hedgehog also seems particularly vulnerable to many aspects of modern life. Perhaps people feel uncomfortable at the way that humanity storms ahead while harmless creatures like the hedgehog are swept aside or are almost literally downtrodden. Maybe people are simply concerned when they see a sick or injured animal and seek to assist it, leading to the development of hundreds of hedgehog carers and wildlife hospitals (see Chapter 11). Our sympathy for the hedgehog, and its own rather unusual, distinctive appearance, also means that it appears in newspaper stories every month, nationwide. It seems to soldier on stoically despite all the vicissitudes of modern life in human-dominated environments, ranging from the suburbs of Liverpool or Edinburgh, to the South Downs or Romney Marsh. Perhaps we also feel a little respect for the spiny underdog doing its best to survive against the odds.

FIG 259. A vast range of hedgehog-themed souvenirs and other commercial goods is now available.

FIG 260. Hobson’s Brewery in Shropshire made a special brew of hedgehog beer as a one-off stunt to raise funds for the BHPS, with a donation of 5p for every bottle sold. It proved so popular that production continued and over 550,000 pints were drunk, raising £30,000 for hedgehogs. Both the brewing and the drinking continue.

But popular support is not just a matter of sympathy or publicity and razzmatazz. The public have also provided help in concrete terms by donating money. In 2016, The Times newspaper focussed its annual Christmas Appeal on hedgehogs, resulting in a gift to the BHPS totalling more than £62,000. This was sufficient to underwrite the cost of employing a full-time ‘Hedgehog Officer’ based in Warwickshire with a remit to promote wildlife interest among local children and encourage practical hedgehog conservation measures among gardeners and householders (Fig. 261). Popularity and public support are vital in keeping the hedgehog on the agenda for parliament and local decision-makers. Oliver Colville’s parliamentary efforts in 2016 gained widespread publicity and approval for his attempt to promote hedgehogs in the House, no doubt enlivening proceedings in the process. Hansard thus became one of the more improbable publications to feature hedgehogs extensively, at least for a while. In the House of Lords, the Marquis of Lothian asked a bland question about the hedgehog’s demise and what was the Government doing about it. The equally bland reply was to the effect that BHPS and PTES were doing a grand job. Such anodyne exchanges may appear to be a waste of time, but they do keep hedgehogs on the agenda in the face of so many other pressures on government. And what’s good for hedgehogs is usually good for other wildlife too. Continued public pressure on ministers results in policy commitments promising a better tomorrow. This pressure is vital, with Britain’s impending departure from the EU offering unique opportunities to reshape national policy towards integration of farming and wildlife conservation in ways that have not been achieved hitherto except on a local scale.

FIG 261. Henry Johnson, (in pale blue) was the first full-time ‘Hedgehog Officer’, funded by the PTES. Simon Thompson and Debbie Wright, attached to Warwickshire Wildlife Trust, and Ali North, attached to Suffolk WT, were all three funded by BHPS. They were charged with the job of raising the profile of hedgehogs and local wildlife conservation.

FIG 262. An early result in Suffolk was a giant mural by ‘ATM’ in King Street, Ipswich, with the blessing of the Borough Council planning department. (Simone Bullion/ Suffolk Wildlife Trust)

SUPPORT FOR UIST HEDGEHOGS

Public support becomes seriously important when an issue arises like the hedgehog cull on the Uists. As explained in Chapters 1 and 11, hedgehogs were released on the Hebridean island of South Uist in the 1970s and began to have a serious impact on important colonies of ground nesting birds. Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH), the agency responsible for dealing with the problem under international agreements, decided that the hedgehog population should be reduced or eliminated by killing as many of them as possible. Eventually, many hundreds of them were killed at a cost of about £130 each in public money (Lovegrove, 2007). The BHPS was among the leading charities that campaigned hard to gain public support for a policy based upon translocation to the mainland rather than killing by lethal injection.

One of Digger Jackson’s conclusions from studying the breeding behaviour of those Hebridean hedgehogs was that removal of adult females would be a priority if the population needed to be significantly reduced, but there was public disquiet about the fate of dependent nestlings if their mothers were removed. It was in response to this concern that the adult females were reprieved during culling operations in order to avoid litters of dependent nestlings starving if their mother was killed. It was not possible to identify with confidence the females that were pregnant or lactating and then release them, because of the difficulty in distinguishing various stages of the female reproductive cycle. To avoid welfare problems, removal of females was therefore confined to the short (two to three weeks) period between coming out of hibernation and getting pregnant. Non-removal of adult females was a very significant concession to public concern, but massively reduced the effectiveness of the cull and increased the probability that it would never be successful in eliminating hedgehogs from the Uists.

SNH were adamant that killing was necessary and hedgehogs could not be simply removed, and to improve catching efficiency, a necessary development if enough animals were to be caught, a plan was drawn up to get dogs to find the hedgehogs and use a shotgun to destroy them. That idea elicited such outrage that the policy lasted barely a week (Fig. 263). People up and down the country were incensed that hedgehogs would be killed, especially when these animals were facing decline on the mainland. The public outcry over the Uist hedgehog cull was enough to fully occupy the SNH Press Officer, with 3,000 protest letters received, but people did not just complain and send emails. They donated £75,000 to support the rescue of doomed hedgehogs (Lovegrove, 2007). This was a very real gesture, made by large numbers of people who felt strongly about the casual condemnation of such an iconic animal. Some of that money made it possible to set up a study that confirmed released animals did not suffer unduly. A few hedgehogs rescued from being killed on the Uists were taken to Hessilhead Wildlife Rescue Trust near Glasgow. From among those, we used 20 females for a follow-up study because they would travel less far than males each night and it would be easier to monitor a larger sample than if males had been included. They were released into an area of amenity grassland at Eglinton Country Park, about 50 km southwest of Glasgow, in April 2005 (Fig. 264). They were radio-tracked each night for a month (Warwick et al., 2006). The three hedgehogs that died all did so within a week of release. These, and the one that died of an existing disease and another that disappeared within 48 hours, were all animals right at the end of hibernation in the worst possible body condition and released directly without being given artificial support. They were likely to have died anyway, even if they had not been taken from the Uists. The remaining 15 hedgehogs were monitored regularly. Two were lost to predation and one drowned. Overall, 12 of the 20 animals survived (60 per cent) and maintained their body mass or increased it despite the challenge of survival in unpromising habitat so soon after hibernation had ended. One of them was 38 per cent heavier by the end of the study. They also interacted normally with indigenous male hedgehogs and 11 of those released females were seen consorting with wild males at various times. Crucially, there was no evidence of a negative impact on welfare directly attributable to translocation.

FIG 263. Using dogs to increase the efficiency of searching for hedgehogs was sensible, but the plan to shoot any that were found was insensitive and lasted barely a week in the face of public opposition.

In 2007, SNH conceded that translocation to the mainland would replace killing as the means of reducing the impact of hedgehogs on the Uist bird colonies and it was donations from the public that made possible a rescue system which ultimately enabled more than 2,400 hedgehogs to be taken off the islands to the mainland between 2008 and 2016 (Pat Holtham, pers comm). None of this would have been possible without such a massive level of popular support.

FIG 264. Hedgehogs from the Uists were released in Eglington Country Park and their survival monitored. Molehills were an encouraging sign that there were probably enough worms and other invertebrates to support hedgehogs, as well as the moles.

HEDGEHOG UNDERPASSES

Another area in which popular support is an important consideration concerns the annual toll on the roads, amounting to tens of thousands of animals (see Chapter 9). Public concern has frequently been expressed over the number of otters that are run over each year and the annual loss of an estimated 50,000 badgers (Harris et al., 1995). There is also an additional monetary cost due to the damage done to cars that are involved in collisions with larger mammals, especially deer. Concern about roadkill is real and justified. In most countries, roadside warning signs inform drivers of the danger of collisions with wildlife, although evidence of their effectiveness in reducing road casualties is lacking (Huijser et al., 2015). Nevertheless, public concern and the need to cater for protected species have led to the construction of special wildlife underpasses when roads are being built. These are meant to allow animals such as otters and badgers to cross the new road without risk of being killed and they represent a relatively minor additional cost for multimillion-pound road construction projects. A similar issue concerns mass mortality among frogs and toads as they migrate to their breeding ponds in the early spring. Large numbers of them splattered on the road is a distressing sight and sometimes threatens the survival of local populations.

Underpasses have been constructed on routes that these animals are known to use regularly, providing an alternative way of crossing the road and reducing the carnage. Wildlife tunnels have met with varying degrees of success and in some cases have been visited by hedgehogs. It could be argued that similar tunnels could be constructed specifically for them, allowing hedgehogs to cross a new road safely. But these animals do not appear to use regular routes in the way that otters, badgers and amphibians do. It is therefore far from obvious where to build an expensive tunnel. The cost of an underpass would be hard to justify and extremely unpopular if it turned out that the hedgehogs never used it. Nor are existing underpasses built for badgers much help to hedgehogs as they are likely to be wary of using them, put off by the smell of their potential enemy (Ward et al., 1997). A survey of 34 mammal underpasses showed badgers used them 2,200 times, but hedgehogs not at all. Work in the UK by Silviu Petrovan at ‘Froglife’ clearly demonstrates that the responses of species to different wildlife underpass designs are varied and complex and we need to refine our understanding of what might make a tunnel tolerable (or even attractive) for hedgehogs. Their effectiveness might also be enhanced by the judicious addition of low fencing or baffles to deflect the animals from crossing a road and direct them towards a tunnel.

However, as noted earlier, hedgehog traffic victims often seem to be clumped along certain short sections of particular roads, whilst other stretches of road remain free of them. This may be due to physical barriers, but might also reflect unattractive roadside habitat. Creating barriers in the form of fencing would reduce the death toll, but at the expense of exacerbating the problem of fragmenting habitats and populations. There is an extensive literature on the principle of mitigating the effects of road construction through the use of wildlife passages of various kinds, particularly in the Netherlands, but also in Australia and North America. There may also be effective ways of managing the nature of road margins to reduce the number of hedgehogs killed. For example, we know from many radio-tracking studies that they like to follow edges and often forage within 5 m of a hedgerow. If a new road is to be built, then ending a hedge well short of it, or strategically planting another, might indeed guide hedgehogs away from danger. It would be hard to gather statistically robust data to demonstrate the effectiveness of such measures, given the relative infrequency with which hedgehogs cross roads or are run over, but such ideas are worth a try. They can’t do any harm and might benefit other species too. The hedgehog’s popularity with the public would be key to getting significant money spent on pursuing such ideas and public pressure could encourage more innovative thinking following the lead set by some progressive European governments.

Another way that numbers of hedgehogs and other mammals killed on roads might be reduced could be to modify the road surface. Tyre noise from passing traffic can be altered by changes in the road surface so that the sounds created have an enhanced ultrasonic component. Laying strips of modified surfacing material could allow traffic to generate penetrating noises inaudible to humans, but potentially serving as a powerful warning for wildlife to keep clear. Trials are being conducted in France to see if it works with greater horseshoe bats.

VOLUNTARY ASSOCIATIONS

There is now a widespread groundswell of public support in favour of conserving wildlife or at least preventing its loss as a result of careless indifference. There is a lot of public sympathy for the various conservation organisations involved, and so there should be in a relatively affluent and civilised country like Britain. We spend huge amounts on supporting our historic and artistic heritage in this country; exactly the same justifications should apply to conserving our natural heritage too. We have major organisations devoted to protection of the environment and its associated biodiversity. The National Trust, for example, now has over 5 million members and, despite its focus on stately homes, is actually responsible for more farms and countryside than any other charity or private landowner. Our 47 county wildlife trusts have more members than any political party and the RSPB, with a million members, now embraces a broad approach to wildlife and not just birds. Smaller charities also make an important contribution, both to plant and animal species and to the wider environment. Increasingly, charities are realising that the hedgehog is a near-perfect tool for engaging with the public, resulting in a proliferation of hedgehog-related campaigns and policies. The same applies to businesses: in 2017, the trade newspaper of Waitrose supermarkets advertised their new ‘breadhogs’ (loaves vaguely resembling hedgehogs), designed to appeal and catch the eye of shoppers sympathetic towards these animals.

Hedgehogs will benefit from all of these developments, but crucially they also have specific support from the British Hedgehog Preservation Society (BHPS), evident in many earlier chapters of this book. The BHPS has its origins in 1982 when Major Adrian Coles, formerly of the SAS and Shropshire County Council, rescued a hedgehog that had become trapped in the cattle grid on his drive. It would never have escaped without help and faced death by starvation. Following this incident, he launched a successful campaign to have ramps installed in every cattle grid in his county, later extended nationwide. The ramps would enable any trapped animals, including hedgehogs, to climb out safely. ‘Major Hedgehog’ became highly instrumental in raising the profile of hedgehogs. A frequent guest on radio, he was made an MBE and a Freeman of the City of London for services to the community. He died in March 2017, aged 86 (Fig. 265).

FIG 265. Adrian Coles, founder of the BHPS, became a Chelsea Pensioner, here appearing in support of Hedgehog Street at the Royal Horticultural Society’s Hampton Court flower show in 2014.

Adrian Coles was not the first to suggest fitting escape ramps to cattle grids, but he succeeded in encouraging other county councils to follow suit and generated a massive response via the media. He ran the BHPS initially from his own home to encourage and give advice on the care of hedgehogs and to foster children’s interest in these animals. His initiative has been carried forward with endless enthusiasm and ingenuity for more than a decade by Fay Vass, who has organised publicity events and two national conferences on the hedgehog. The Society has about 11,000 members and its office supports a sales operation, with a changing stock of inventive and popular hedgehog-themed merchandise. It issues newsletters and also keeps a close watch on hedgehogs in the media, now expanded to include Twitter and Facebook (with nearly 42,000 and 165,000 followers respectively). BHPS provides specialist help for individual hedgehog carers where necessary. It supports education projects and has been hugely effective in raising the profile of this species by creating ‘Hedgehog Awareness Week’ in early summer. It has pursued campaigns to reduce litter that is harmful to animals and won a long battle with McDonald’s to get their packaging changed so that hedgehogs would not get their heads stuck in discarded containers when seeking to benefit from the food remains they contain. In 2015, BHPS pressed successfully for similar changes to the packaging for milkshakes used by Kentucky Fried Chicken outlets, reducing the threat to hedgehogs and including an embossed warning that ‘litter harms wildlife’. Another campaign sought to reduce the huge number of elastic bands discarded by postmen on their rounds, creating frequent welfare problems for pets and wildlife that eat them and ugly cases of entanglement involving hedgehogs. Self-adhesive labels have been issued to buyers and users of strimmers and mowing machines, urging their careful use to avoid injury to hedgehogs. The BHPS has also supported several major research projects and many smaller ones, including some of my own.

But newsletters and publicity are not enough. The BHPS Trustees have recognised that there is only so much that can be achieved from an office. What hedgehogs need is a lot of focused support on the ground. In 2015, a decision was taken to fund a full-time ‘Hedgehog Officer’, Simon Thompson, attached to the Warwickshire Wildlife Trust. The role would entail reaching out to schools to highlight the hedgehog and the strong wildlife conservation messages that go with it. There would also be attempts made to establish ‘Hedgehog Improvement Areas’, where landowners and householders would be visited personally to encourage hedgehog support on the ground. There were over 150 applicants for the job and the project gained sufficient attention that it was even reported appreciatively in The Wall Street Journal. Reaching out to the local people, especially via schools, was sufficiently successful that the project was extended to include funds for a second person. Another full-time employee with a similar brief was funded in 2016 to be based with the Suffolk Wildlife Trust. This too attracted a large number of applicants, from Britain and abroad, although the associated press coverage tended to highlight the salary rather than the human and hedgehog issues involved. Meanwhile, the PTES had engaged Henry Johnson as their first full-time ‘Hedgehog Officer’, tasked with promoting the hedgehog’s interests nationally to considerable effect (see Fig. 261).

It may seem eccentric and perhaps old-fashioned to focus on just one species and many professional ecologists would argue that wildlife conservation needs to have a broader approach. However, the hedgehog is a familiar animal to which many important ecological principles and conservation messages can be attached. It is also a popular creature that elicits sympathy and virtually no hostility. It is an ideal flagship species to carry forward important ecological and conservation principles to a broad public and encourage ordinary people to become involved with wildlife in their own personal environment. Moreover, what is beneficial to hedgehogs on the ground is also good for a wide range of other species to which most people would never give a thought.

Like the hedgehog itself, the BHPS has a slightly quirky feel about it, but membership is not expensive and makes a nice birthday gift for children. Its worthy aims have also struck a chord with many people who have left generous legacies to support hedgehogs and the wildlife conservation principles that are associated with them. Legacies to charities are tax free, so they enable people to give some of their money to support good causes instead of losing it to the Treasury as Inheritance Tax (‘death duties’). That way one can steer funds towards worthy projects rather than having it taken as tax and then used for general government expenditure. This principle has been enormously effective in supporting wildlife in recent decades and has inspired many to leave generous legacies for conservation charities that have often achieved far more than the benefactor could ever have imagined in their lifetime.

Among the donors was Dilys Breese, a renowned television and radio producer for the BBC Natural History Unit. She was responsible for many popular radio and TV programmes (some of which involved me too) and in 1982 she made a film called The Great Hedgehog Mystery that attracted an extraordinarily large number of viewers, over 12 million when it was first broadcast (more than watched ‘Match of the Day’, the BBC’s leading sports programme at that time). The programme’s success boosted both her professional status and her own fondness for hedgehogs. When she died in 2007, Dilys left a substantial legacy which provided the vital foundation for BHPS and PTES to develop the joint project ‘Hedgehog Street’ which has been so successful in engaging interest in supporting many practical activities that benefit hedgehogs.

HEDGEHOG STREET AND MAKING HEDGEHOG-FRIENDLY NEIGHBOURHOODS

‘Hedgehog Street’ (www.hedgehogstreet.org) was launched on the BBC’s ‘Springwatch’ broadcast in June 2011 to become a focus for a strategy to help the declining hedgehog population, specifically in gardens and suburban habitats. Hopefully, it would also have community benefits by drawing neighbours together in sharing a street-wide strategy for wildlife. A resource pack was produced that included instructions on what to do to help hedgehogs and within a year 20,000 of these had been distributed.

FIG 266. The author, appearing in support of Hedgehog Street at the Royal Horticultural Society’s Hampton Court flower show in 2014.

FIG 267. The award-winning hedgehog garden designed by Tracey Foster for the Royal Horticultural Society’s Hampton Court flower show in 2014.

There are said to be 23 million gardens in Britain, an area equivalent to the size of Suffolk. Gardens are one of the key habitats for hedgehogs, so a strategic focus on them is essential. So it was also decided to invest in having a presence at the Royal Horticultural Society’s 2014 Hampton Court Flower Show, a venue second only to the Chelsea Flower Show in national prominence among gardeners. A specialist designer, Tracey Foster, was engaged to create a demonstration garden featuring good things for hedgehogs that could also be aesthetically pleasing (Fig. 267). The result was something novel and appealing. The garden won a Gold Medal and ‘best of show’ awards, gaining massive publicity for hedgehogs and the practical ways in which gardeners could help them. The idea was also taken up by Harlow Carr Gardens in Yorkshire, where they created a semi-permanent exhibit with a similar theme that is likely to be seen by up to 400,000 visitors a year.

The power of modern communications systems is such that it is now possible to reach out to far more people than in the past. Effective use of this opportunity enabled Hedgehog Street to recruit over 47,000 ‘Hedgehog Champions’ by the end of 2017, all committed to doing something positive to benefit local hedgehog populations. The suggested actions are based upon research and practical experience, with free downloadable resources now available online for registered users, with forums and photo galleries to encourage the sharing of experiences. Many householders already put out food for wildlife, but advice is available on what sort of food is best and what might be the benefits to hedgehogs. It is also essential to create ‘Hedgehog Highways’, linking gardens and increasing access to wider areas of habitat (Fig. 268). Winter and summer nest sites are important too, and understanding what the hedgehog needs enables gardeners to provide nesting opportunities at minimal cost. Special nest boxes can be purchased or constructed and 4,000 of them were installed in response to encouragement from ‘Hedgehog Street’. The dangers of setting light to bonfires can be highlighted and also the need to build an escape route from the garden pond (Fig. 269). There are ideas for the safe control of slugs, where gardeners feel they are a serious problem. These are all practical suggestions for ways of alleviating the threats described in earlier chapters of this book. They can do no harm and might significantly benefit hedgehogs, and probably other species too. An independent survey (conducted by BBC Gardeners’ World magazine) revealed that 60 per cent of their readers had already done something in their garden to help hedgehogs: 36 per cent avoided using slug pellets, 34 per cent retained leaves and twigs for nesting, 26 per cent checked for hedgehogs before using a strimmer and 21 per cent checked before lighting bonfires. The message is getting through!

FIG 268. Hedgehog Highways, holes in fences that link gardens and other open spaces, allow access to the larger areas that the animals need. A concrete block, pipe or brick tunnel reduces the headroom so that most longer-legged animals like cats, dogs and foxes are excluded. Over 9,000 gardens have now been linked in this way

FIG 269. A simple escape ramp in the garden pond (or swimming pool) will save hedgehogs from drowning if they fall in. Cheaper still, a piece of chicken wire will help the animals to climb out.

FIG 270. Offering food to hedgehogs within a wire shelter or underneath a low covering will reduce access for longer-legged animals like foxes and dogs. Hedgehogs access this one via a concrete block tunnel (visible at the back) that excludes cats and magpies.

Particularly important has been getting the message across about habitat continuity. Most gardens are far too small to support even one hedgehog; they need access to others. The campaign to encourage householders to make small openings in their fences to permit hedgehogs to move more freely through a fragmented urban area has been very successful. Over 9,000 gardens have now been linked via these special Hedgehog Highways created by householders. The idea has been met with some wariness because fences are meant to keep things out and maintain exclusivity. Allowing access to hedgehogs might encourage unwanted dogs into the precious flowerbeds or allow the neighbour’s cat to enter and threaten one’s garden birds. Again, practical advice is available and the use of bricks or a concrete block to convert the hedgehog-sized hole into a tunnel will exclude most unwanted visitors. Food can be offered inside an enclosed feeding station to which animals larger than hedgehogs cannot easily gain access (Fig. 270). These are all direct actions that cost little, do no harm and may go a long way towards helping hedgehogs to survive in an urban setting. Ideas can also make people think and just thinking helps to awaken more ideas and perceptions that enable people to make better gardens, benefitting both themselves and the various creatures that share the same home (Bourne, 2017).

In addition to privately owned gardens, hedgehogs also benefit from access to thousands of hectares of parks, cemeteries, allotments and other forms of public amenity land. The PTES has reached out to the managers of these vital areas by offering courses (21 so far) advising on steps that help support existing hedgehog populations and also avoid accidental loss through unwitting, but harmful, land management practices.

FIG 271. A line of new houses linked with garages prevents hedgehogs travelling between the rear garden, and front gardens or crossing the road to open country on the other side. When planning new housing estates, it would cost little to incorporate more hedgehog-friendly features, especially gaps in fences and between houses.

More strategically, and especially as we begin a massive national increase in housebuilding, developers are being urged to take account of hedgehogs in areas scheduled for new housing by avoiding unnecessary destruction of nesting or foraging areas. Some developers (like Barratt/Kingsbrook) are including in their plans as many supportive features as possible (Fig. 271). Several of the biggest house-builder companies have promised to install and label Hedgehog Highways in new housing developments as they take shape. The challenge is to demonstrate that hedgehog-friendly homes are attractive (or at least have a neutral impact) for prospective buyers. But the power of the ‘hedgehog brand’ should not be underestimated and these features should also improve the appeal (and value) of the new homes!

FIG 272. Hedgehogs are popular in other countries too, enough to feature on special editions of postage stamps.

Enthusiasm for hedgehogs is not confined to Britain (Fig. 272). In Germany, the volunteer network ‘Pro Igel’ (‘for the hedgehog’ – www.pro-igel.de) founded in 1996 continues to publish a regular newsletter for carers and well-wishers in the country. It has a counterpart in Switzerland and, as in Britain, these groups are driven by a concern for hedgehogs among the public and a wide range of non-professional biologists. More formally, there is also a European Hedgehog Research Group (EHRG), a collection of researchers from across Europe. They first met in Arendal, Norway, in 1996 at an event organised by Beate Johansen, with seven subsequent meetings in other countries. The EHRG is now administered by the PTES via a Google Group. As of April 2017, it included 66 members and will re-form as personnel change, meeting whenever there are enough researchers wanting to do so. These activities and others foster the exchange of ideas about studying and supporting hedgehogs, helping to maintain a high profile for this species and slowly enhance our understanding of its biology and conservation needs.

HEDGEHOGS AND EVERYDAY TECHNOLOGY

One slightly worrying technical development is the availability of devices that emit ultrasonic sound pulses to deter or scare off unwanted animals like rats, cats or moles. It would be a shame if people were to make an effort to ensure their garden was hedgehog-friendly and then deploy a machine to deter cats which also scares away hedgehogs. There is nothing special about ultrasonics, they are simply sounds that are too high-pitched for humans to hear, so they do not trouble us or the neighbours. But they are within the hearing range of certain other mammals (bats, for example) and could be upsetting hedgehogs. Alternatively, animals may learn to ignore them as they often do with other loud sounds. Or the ultrasonic devices may not actually work at all. There used to be a cheap ultrasonic whistle available that could be fitted to car bumpers ostensibly to warn hedgehogs of an approaching vehicle, but cars are noisy and well lit at night, so their approach hardly needs advertising ultrasonically. The one I purchased would not emit any useful sounds at all.