The minds of men are mirrors to one another, not only because they reflect each other’s emotions, but also because those rays of passions, sentiments and opinions may be often reverberated…—David Hume

Stress and its impact on health and wellbeing do not begin and end with the patient. If patients can be at extreme risk from stress, health professionals of all specialties can be doubly so.

Physical and emotional wellbeing are dependent not just on the practitioner’s capacity to achieve and maintain allostasis in his own life, but also on how resistant he may be to the daily, invisible risk of ‘infection’ by his patients’ distress.

Patients expect the practitioners they consult to care about their problems. Doctors and other health professionals are encouraged—at least in their training—to display ‘empathy’ towards their patients. By understanding and sharing another person’s feelings and ideas, it is widely believed we deepen our ability to help.

This is undoubtedly true. Empathy is a valuable tool for any health professional, and one deeply valued by patients. But unless it is understood and managed, it comes at a price.

We can be reasonably confident that empathy is necessary for the survival of our species. The ability to share feelings and experiences vicariously allows us to work together for the greater good of the group. Conversely, the apparent inability of some people to care about the impact of their negative actions on others usually fills us with profound revulsion, as if some deep and sacred law has been violated.

Many training programs suggest that empathy is a learned skill. In fact, as many researchers are now beginning to suspect, people cannot not be empathetic, supposing they are free of any ‘psychopathic’ disorders that, for reasons not yet understood, prevent some individuals from even comprehending, much less experiencing, any of the emotions normally elicited by witnessing someone else’s pain. Everyone has experienced wincing in sympathy when they see someone else stumble or trip. Even though they might laugh at the comedian who slips on a banana skin, they do so as a release of tension caused by seeing someone ‘like us’ suffer ignominy or pain. It is a natural, automatic response.

Medical students are given conflicting messages during training: be empathetic, but remain dispassionate when dealing with patients’ pain and discomfort. Under pressure, many physicians take the second route, and understandably so. A doctor who has problems with blood or open wounds is of no use to the patient. But, it is important for health professionals to know that, while they might learn to conceal their feelings (even from themselves), millions of years of evolution have ensured that the response is wired into their neurology.

For example, when you see someone else’s hand being pricked by a needle, the motor neurons in the same area on your own equivalent hand freeze as if you have received the needle-prick yourself. Using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for their studies, researchers have been able to establish that the ‘social dimension’ of pain extends to basic, sensorimotor levels of neural processing.73 ‘Somatic empathy’—the body’s automatic response to the neurological state of another person74—is there, whether it is noticed or not.

The empathic ‘mirror’

The discovery in the 1990s of a group of cells called ‘mirror neurons’ offers some explanation for how we translate exteroceptive information into internal, ‘psychosomatic’ experience. This brain-to-brain communication system synchronizes neural firing patterns so that the observer ‘feels’ someone else’s experience as if it is happening to her. Mirror neurons probably also allow people to learn by observing, and neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran has suggested they may have been the driving force of the ‘great leap forward’ in human cultural evolution 50,000 years ago.75

With the advent of language, the problem becomes more complicated. When the subject uses limited descriptions of his experience—often nominalized words such as ‘depression’, ‘anxiety’, ‘relationship’, ‘anger’—the listener is required to plumb the depths of his own experience to attach meaning.

Known as a ‘transderivational search’ (TDS), this has its dangers. Unless the listener fills in the deleted part of the patient’s communication, he is repeatedly re-entering and re-experiencing his own past experiences, and paying the price for reactivating the cascade of neurochemicals associated with pain and distress. He may ‘understand’ what the patient is going through, and he may ‘feel for’ her. He may think of himself, and be thought of, as a ‘good person’. However, he not only reduces his ability to fully help the patient extricate herself from her problem, but also suffers the corrosive effects of the patient’s distress.

Psychologist Daniel Stern warns of the risks of being ‘captured’76 by another person’s nervous system; the result of this is what Elaine Hatfield and her colleagues at the University of Hawaii call ‘emotional contagion’.77

Hatfield’s theory—in line with NLP’s earlier observation that physiology informs feeling, and vice versa—suggests that the listener’s unconscious mimicry of the speaker’s posture, facial expressions, tonality, breathing, etc, may ‘infect’ her with the speaker’s emotions.

The Botox effect

Conversely, if the speaker’s facial expressions are inhibited, say, by the use of Botox, his ability to read the emotions of other people is impaired. ‘Embodied emotion perception’ depends both on interpreting the nonverbal signals of others, and on being able to display emotions ourselves.78 Like many of our animal cousins, humans are in a constant, dynamic, feedback-looped relationship with each other.

Hatfield suggests that emotional contagion is an unavoidable consequence of human interaction. Although we fully agree with the first part of Hatfield’s conclusions, we question the inevitably of ‘contagion’. Taking on the subject’s experience ‘as if’ it is the practitioner’s own is an example of association, well known in NLP. Put another way, she leaves her own subjective experience (dissociates) and ‘steps into’ the patient’s (associates).

Even though this is an imaginal act, neuroscience can now demonstrate that there is little functional difference between a physical and an imagined action. You can even weaken or strengthen your muscles by simple mental rehearsal.79 Your ability deliberately to associate into and dissociate from a patient’s experience is the key to achieving engagement and emotional resonance, without suffering negative effects.

This capacity, as we will later demonstrate, can also be harnessed to therapeutic effect. Medical NLP recognizes three ‘points of view’ that allow us effectively to manage our relationships with others (Figure 3.1). However, failure to control these positions and the time we spend in them can lead to a number of undesirable consequences. (Please note that we may often observe mismanagement of these positions among patients. For example, someone who takes responsibility for spousal abuse because ‘I make him mad’ may be stuck in Position 2.)

| Perspective | Description | Positive effect | Negative effect |

| 1. Self | Associated into one’s own body, engaged in subjective processing of data, feelings, behaviours | Allows us to apply learning and experience that the other may lack | To the exclusion of 2 or 3: single-mindedness, refusal to consider information that does not match own schema, ‘selfishness’, etc. |

| 2. Other | Dissociated from self, associated into the other, sensing or imagining his feelings, responses, etc. | Open to other possibilities, increased understanding and empathy, increased social and emotional connectedness | To the exclusion of 1 and 3: Overinvolvement in the other’s problems, loss of ego boundaries, physical and emotional overidentification, ‘co-dependence’, emotional contagion, burnout |

| 3. Observer | Objective, ‘as if’ from physically and emotionally detached viewpoint | Yields information about the relationship between 1 and 2, open-mindedness, avoids bias and premature cognitive closure, reduces overemotionalism | To the exclusion of 1 and 2: Detached, uninvolved, uncaring, ‘cold’, machine-like |

Figure 3.1 Perceptual positions

As we acquire flexibility in managing these aspects of our relationships with patients, we also learn how to avoid the defense mechanisms adopted by some health professionals to cope with daily exposure to illness, pain, and fear—withdrawal, dissociation, and alienation from the ‘human connection’ on which effective consultation should be based (permanently in Position 3).

When entropy prevails

Various authors have proposed different names for the negative risks practitioners face, including ‘burnout’, ‘compassion fatigue’, ‘vicarious traumatization’, and ‘secondary traumatization’. We do not propose to discuss the differences between each of these models; it is enough to recognize that the signs and symptoms of allostatic load among practitioners are similar to those of patients.

These signs and symptoms are both communications of, and attempts to resolve, imbalance. How these are experienced and expressed may depend on the particular strategy or strategies the subject unconsciously adopts. Strategies are chains of internal actions (visualization, self-talk, feelings) that, when activated, in sequence, always result in the same behaviors and experiences. We discuss the subject in greater detail in later chapters, as well as in Appendix D (pages 367 to 369).

Figure 3.2 (below) demonstrates the effects of three behavioral responses to mounting allostatic load: Displacement, Obstruction, and Distraction.

We assume these coping strategies are learned during childhood, when they might have served a purpose. As we mature, however, they tend to become less socially acceptable and more detrimental to health and wellbeing.

Whether some effects, such as anxiety and aggression, result from sympathetic arousal, and others, including withdrawal and depression, from parasympathetic arousal, is still a subject of some contention among researchers. However, it is safe to assume that some or all these responses occur when the balance of the autonomic nervous system is disturbed. Rather than facilitating the flow of energy, these strategies all have the potential for spiraling down into more serious dysfunctions and disease.

| Response | Effect | |

| Displacement: | ||

| Attempts to dissipate energy | Aggression, excitability, anxiety, crying, talking, physical activity, compulsive behaviour, etc. | |

| Obstruction: | ||

| Attempts to prevent energy entering the system | Withdrawal, depression, loss of energy and appetite, etc. | |

| Distraction: | ||

| Attempts to divert from feelings of disease | Dissociation, excessive use of food, alcohol, sex. Smoking and substance abuse, absorption in passive entertainment, such as television, etc. |

Figure 3.2 Response to allostatic load

The stress-proof individual

Some people, however, undoubtedly have the ability to engage fully with the day-to-day challenges of work and life while somehow remaining impervious to stress and its effects. Although this may be partly genetic, research indicates that the ability to flourish in the face of challenge (in terms of the model outlined in the previous chapter, effectively to maintain allostasis) is marked by certain qualities usually ignored in orthodox medicine.

Hans Selye’s largely reductionist approach (that the stress response is purely physiological) has been substantially modified by the discovery that perception of stress can both trigger and regulate allostatic load.

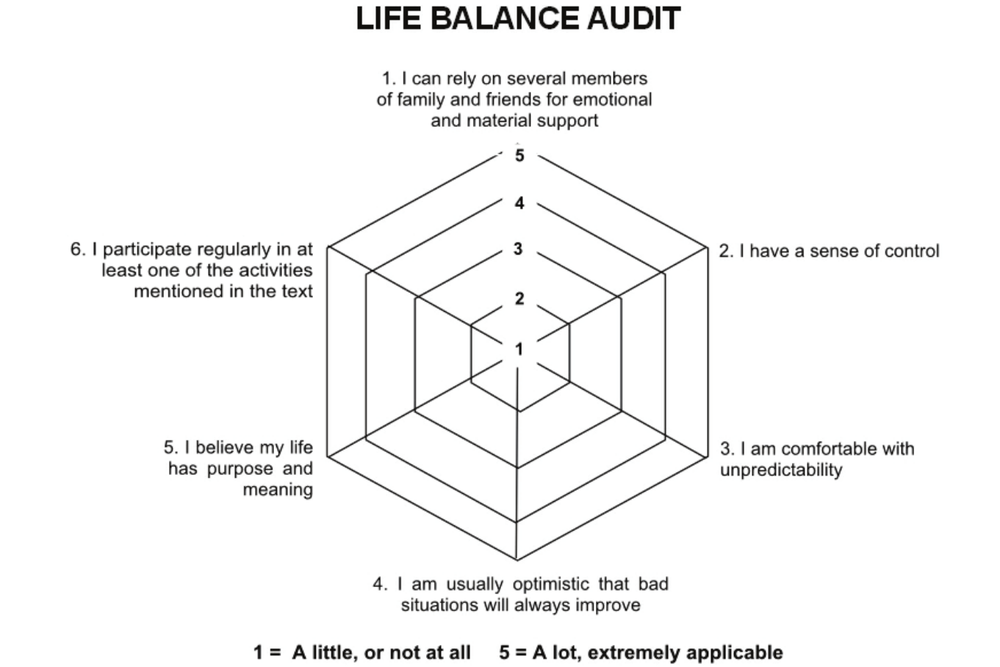

Known as psychological modulators, these fall into six main categories: social support/connectedness; a sense of control; predictability; outlook (optimistic vs. pessimistic); meaning or purpose; and the ability to dissipate frustration. All six are open to modification by the principles and techniques featured later in this book.

Although exploring how these psychosocial variables may be affecting patients with medically unexplained disorders could provide the practitioner with valuable insights, we urge you to use the following information and Figure 3.1 to audit the psychological modulators that may be affecting your own allostatic load.

Note: Read the sections that follow, then record a score from 1 (meaning ‘a little’, or ‘not at all’) to 5 (meaning ‘a lot’, or ‘extremely applicable’) on each corresponding segment of Figure 3.3. When you have finished, connect the dots to make a six-pointed shape which will provide a clear visual representation of your strengths and weaknesses.

Figure 3.3 Life balance audit

1. Social support and connectedness

Researchers investigating strikingly low rates of myocardial infarction, reported in the 1940s from the little Pennsylvanian town of Roseto, where they expected to find a fit, tobacco- and alcohol-free community enjoying all the benefits of clean-living. When they arrived, they found as many smokers, drinkers, and couch potatoes as in the rest of the country, where heart disease was on the rise.

The difference between Roseto and other similar towns, the researchers discovered, was a particularly cohesive social structure. Somehow, the closeness Rosetans enjoyed inoculated them against cardiac problems. Predictably, as the community became steadily more ‘Americanized’, the protection disappeared.

A 50-year longitudinal study, published in 1992, categorically established that social support and connectedness had provided a powerfully salutogenic (health-promoting) effect on the heart.80

Nor was this a random fluctuation affecting a small, isolated community.

A number of studies have confirmed that host resistance to a wide range of illnesses is affected by the social context in which you live and the support you feel you receive. A recent study of 2,264 women diagnosed with breast cancer concluded that those without strong social bonds were up to 61% more likely to die within three years of diagnosis.

According to Dr. Candyce Kroenke, lead researcher at the Kaiser Permanente Research Center, California, the risk of death equals well-established risk factors, including smoking and alcohol consumption, and exceeds the influence of other risk factors such as physical inactivity and obesity.81

At least two major studies have suggested that loneliness can double the risk of elderly people developing Alzheimer-like diseases. Interestingly, the studies all suggest that feelings of loneliness, rather than social isolation itself, may cause the corrosive effects of dementia.82,83

Key factors in social integration have been identified as having someone to confide in, who can help with financial issues and offer practical support, such as baby-sitting, when you need it, and with whom you can discuss problems and share solutions.84

Some of the established benefits of social support and connectedness include: extended lifespan (double that of people with low social ties)85; improved recovery from heart attack (three times better for those with high social ties)86; reduced progression from HIV to Aids87; and even protection from the common cold.88

Question 1 is: Do you feel supported by your family and friends?

2. A sense of control

Feeling you are in control of your work and personal life is one of the best predictors of a long and healthy life. Conversely, feeling victimized by unpredictable forces outside of your control can be a killer. One large-scale study has revealed that people who feel they have little or no control over their lives have a 30% increased likelihood of dying prematurely than those who score highest in tests measuring a sense of power and control.89

Whether we look at rats or humans, the effect is the same. Where predictability and control are low, and environmental or occupational stress is high, the risk of cardiovascular and metabolic disease soars. However, for human beings there is hope. Happily for our survival in a stressful world, not only can health improve as control is restored, but even knowing that we have choices can significantly offset the effects of even major life-challenges90, reduce our experience of pain and need for medication91, and measurably increase longevity, even in later life.92

Question 2 is: How much control do I feel I have in my life?

3. Predictability

Our ability to predict events, such as pain and stressful situations, helps arm us against their effects. Habituation—the regularity with which stressful events occur—also helps us cope. Studies of urban populations in Britain who faced regular nightly air raids during World War 2 showed a greater level of resilience to stress diseases than their counterparts in the suburbs, where bombing was substantially more erratic.

Once again, perception is the key to how people respond. If your worldview is one of being at the mercy of random events—most of which are negative—allostatic load is inevitable. If you enjoy surprises (and there are many who do), the emotional response to the resultant surge in stress chemicals and endorphins is likely to be interpreted as excitement.

It must be emphasized that predictability, like control, can have its downside. Just as a misplaced sense of control over issues that are beyond our influence can be counter-productive, so can too much predictability. Studies of work-related stress have repeatedly shown that highly repetitive (read: boring) tasks can result in high levels of job dissatisfaction, absenteeism, and blood pressure. Less predictable work interspersed with the production-line activities reverses the effects.93

Question 3 is: How comfortable am I with uncertainty?

4. Positive expectancy

Positive expectancy (dismissed as ‘hope’ before social scientists decided to rebrand it to make mainstream scientists more accepting) has many health benefits. Multiple studies show that an optimistic outlook, by both the patient and the practitioner, can have a significant impact on clinical outcomes.94,95,96

Simply put, believing (and acting as if) the glass is half-full is good for your health. Even better is entertaining the possibility that the glass—or, any other vessel you choose to bring to the well—is full to over-flowing.

However, there is a caveat. Blind ‘hope’, as advanced by many self-help books, may have little impact on disease outcome, and exhorting someone to remain hopeful in difficult circumstances can prove taxing and lead to depression and self-blame. Realism, coupled with the anticipation of improvement, however small, can moderate the stress chemicals that an otherwise serious or critical situation can trigger.

A landmark study, referred to by Robert Sapolsky in his highly readable book on stress and coping, Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers,97 found that parents whose children had been diagnosed with cancer showed only a moderate rise in stress chemical levels when told there was a 25% risk of death.

The reason for this, the study concluded, was that odds of 75% of survival were perceived as miraculously high. As Sapolsky observes, it is not so much the ‘reality’ of the situation that affects our response, but the meaning we ascribe to it.

Question 4 is: How much do I expect my situation, however challenging, to improve?

5. Meaning, purpose, and spirituality

The way we evaluate past, and anticipate future, events can influence many aspects of our experience, including our health and wellbeing.

Large-scale and longitudinal studies, such as those carried out at Harvard University and Harvard School of Public Health, have demonstrated that explanatory styles—whether we apply an optimistic or a pessimistic spin to the meaning of our experience—are strong indicators of our future health status.98,99

Meaning is governed by many variables. Meta-analyses show that those people who are strongly committed to a religious belief and practice are nearly a third more likely to survive serious illness than those who hold no religious belief.100

A common factor of those with strong religious beliefs is an acceptance of events, positive or negative, as ‘God’s will’. Studies such as these arouse much controversy in scientific circles.

The most frequently encountered argument against a ‘faith effect’ is that religious people tend to follow healthier lifestyles and/or enjoy greater social integration than their non-religious counterparts. However, the 2000 study cited above (by Michael McCullough and colleagues) established that the highly engaged ‘believers’ lived significantly longer, even after the researchers accounted statistically for health behavior, physical and mental health, race, gender, and social support.

Discussing spirituality with their patients is something most practitioners avoid. And yet, holding some larger organizing belief in which we are a smaller, yet nonetheless important, part proves to be a significant part in achieving and maintaining allostasis. We (the authors) do not intend to equate ‘spirituality’ with ‘religion’, and we advise health professionals to be equally cautious. What we are more interested in, and what appears to have a greater impact on health, is a belief that the patient’s life has some purpose or meaning as a part of a greater whole.

This may express itself as a deep commitment to an organized religion, or as an important goal or mission, such as ‘being there for the children’. We are greatly inspired by the experiences of Austrian psychiatrist Viktor Frankl, who was arrested by the Nazis in 1942 and deported with his family to Theresienstadt, a notorious concentration camp set up by the Germans near Prague. During the following three years, incarcerated in the death camps of Auschwitz, Dachau, and Turkheim, Frankl lost his parents, his brother, and his wife, Tilly. Frankl himself survived, despite nearly succumbing to typhoid fever during the last months of the war.

His seminal work, Man’s Search for Meaning,101 recounts both his experiences and conclusions. Frankl spent his time at the very edge of annihilation observing his fellow prisoners, searching out the distinctions between those who survived and those who succumbed without struggle.

His observations suggested that those who looked for and found a sense of meaning in their lives—in other words, who believed they still had a mission to be fulfilled—and were free to choose their responses to whatever happened to them, were best equipped to transcend their circumstances and flourish, no matter how terrible those circumstances might be.

These two beliefs, in a mission or purpose, and the ability to choose our responses, are central to Medical NLP’s therapeutic approach. Many of the principles and techniques later presented are aimed at achieving these ends.

Question 5 is in two parts:

The first part to consider (but not mark) is: What do you find helps you to cope when you have a problem or challenge? The second, which should be scored on the audit, is: How much does this help?

6. Dissipation

We draw a distinction between dissipation and displacement (yelling, crying, punching a wall, etc), none of which has been shown effectively to reduce chronic allostatic load, and may even worsen it.

As Figure 3.2 (see page 34) indicates, displacement is usually counterproductive—physically, psychologically, and socially. Dissipation, on the other hand, may be incorporated into an ongoing program, designed to counter-balance, or even down-regulate, the fight-or-flight response. Some examples may be: regular exercise, especially light aerobic workouts, yoga, martial arts, and meditation (see Appendix A, pages 357 to 360). By ‘regular’, we mean at least four times a week for aerobic exercise and at least once a day for yoga, meditation, T’ai chi etc. Practiced correctly, these, and the resonant frequency breathing referred to elsewhere (see pages 258 to 259), will all improve heart rate regularity (HRV), which we also discuss in greater detail later in this book.

However, when making a lifestyle change to facilitate allostasis by dissipation, it is important to select an activity you find satisfying. The positive effects are directly related to perceiving your program as enjoyable. If it is not, find something else.

Question 6 is: How much ‘downtime’ do you allow yourself (this should involve at least one regular practice selected from the suggestions above)?

Now, unless you are a DC Comic™ superhero, you will have found areas of deficiency in your own life balance audit. This is valuable information, and we suggest you make a note of any area or areas open to improvement to use as material for later exercises. Of course, the audit can be used as a diagnostic tool with your patients, family, and friends.

EXERCISES

1. Practice ‘mirroring’ the posture, breathing patterns, and pitch, rhythm, and tonality of speech of a partner, and notice how this changes your internal ‘state’. This is the effect of being in Position 2 in Figure 3.1 on page 32. (Only do this with the agreement of your partner, or where you can be sure you can do it without drawing attention to yourself. Until you are proficient in mirroring, you need to be discreet to avoid giving offense.)

2. Now, step back into Position 1. Make sure you are fully associated, seeing through your own eyes, hearing through your own ears, and feeling with your own body.

3. Imagine floating out of your body and up into an ‘observer’ position. Notice the reduction or absence of emotions. Practice watching your interaction with your partner as if you were a neutral observer. Suspend comment or judgment.

4. Now, step back into Position 1. Make sure you are fully associated, seeing through your own eyes, hearing through your own ears, and feeling with your own body.

5. Practice these four steps as often as possible, until you can move easily and safely in and out of each position at will.

6. Important note: Always end the exercise by re-associating into your own ‘self’. From this point on, make sure you are back in Position 1 after seeing each patient, and especially at the end of the day.

Notes

73. Avenanti A, Bueti D, Galati G, Aglioti SM (2005) Transcranial magnetic stimulation highlights the sensorimotor side of empathy for pain. Nature Neuroscience 8: 955–60.

74. Ax AA (1964) Goals and methods of psychophysiology. Psychophysiology 1: 8–25.

75. Ramachandran V. http://edge.org/conversation/mirror-neurons-and-imitation-learning-as-the-driving-force-behind-the-great-leap-forward-in-human-evolution

76. Stern D (2002) Attachment: from early childhood through the lifespan. (Conference presentation, audio recording 609–17). Los Angeles: Lifespan Institute.

77. Hatfield E, Cacioppo JT, Rapson RL (1994) Emotional Contagion: Studies in Emotional and Social Interaction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

78. Neal DT, Chartrand TL (2011) Embodied Emotion Perception: Amplifying and Dampening Facial Feedback Modulates Emotion Perception Accuracy. Social Psychological and Personality Science, April 21.

79. Yue G, Cole KJ (1992) Strength increases from the motor program: comparison of training with maximal voluntary and imagined muscle contractions. Journal of Neurophysiology 67(5): 114–23.

80. Egolf B, Lasker J, Wolf S, Potvin L (1992) The Roseto effect: a 50-year comparison of mortality rates. American Journal of Public Health 82(8): 1089–92.

81. Kaiser Permanente, news release, Nov. 9, 2012.

82. Wilson RS et al (2007) Loneliness and Risk of Alzheimer Disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 64(2): 234-240.

83. Holwerda TJ et al (2012) Feelings of loneliness, but not social isolation, predict dementia onset: results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: http://jnnp.bmj.com/content/early/

2012/11/06/jnnp-2012-302755

84. Anderson NB, Anderson PE (2003) Emotional Longevity. New York: Viking Penguin.

85. House JS, Robbins C, Metzner HL (1982) The association of social relationships and activities with mortality: prospective evidence from the Tecumseh Community Health Study. American Journal of Epidemiology 116: 123–40.

86. Berkman LF, Leo-Summers L, Horwitz RI (1992) Emotional support and survival following myocardial infarction: a prospective, population-based study of the elderly. Annals of Internal Medicine 117: 1003–9.

87. Leserman J et al (2000) Impact of stressful life events, depression, social support, coping and cortisol. American Journal of Psychiatry 157: 1221–28.

88. Cohen S et al (1997) Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. Journal of the American Medical Association 277: 1940–4.

89. Seeman M, Lewis S (1995) Powerlessness, health and mortality: a longitudinal study of older men and mature women. Social Science in Medicine 41: 517–25.

90. Wolff C, Friedman S, Hofer M, Mason J (1964) Relationship between psychological defences and mean urinary 17-hydroxycorti-costeroid excretion rates. Psychosomatic Medicine 26: 576–91.

91. Chapman C (1989) Giving the patient control of opioid analgesic administration. In Hill C, Field W (eds) Advances in Pain Research and Therapy, vol. II. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

92. Rodin J (1986) Ageing and health: effects of the sense of control. Science 233: 1271–6.

93. Melin B, Lunberg U, Soderlund J, Grandqvist M (1999) Psychological and physiological stress reactions of male and female assembly workers: a comparison between two different forms of work organisation. Journal of Organisational Psychology 20: 47–61.

94. Segerstrom S, Sephton S (2010) Optimistic expectancies and cell-mediated immunity: The role of positive affect. Psychological Science 21(3): 448-55.

95. Schwartz, T. Psychologist and scientist Suzanne Segerstrom 90 studies optimism and the immune system. Chronicle. Online at http://psychology.about.com/od/PositivePsychology/a/

benefits-of-positive-thinking.htm Goode, E. (2003) Power of Positive Thinking May Have a Health Benefit, Study Says. The New York Times. Online at http://www.nytimes.com/2003/09/02/health/power-of-positive-thinking-may-have-a-health-benefit-study-says.html

96. Goleman D (1987) Research affirms power of positive thinking. The New York Times. Found online at: http://www.nytimes.com/1987/02/03/science/research-affirms-power-of-positive-thinking.htmll

97. Sapolsky R (2004) Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers: The Guide to Stress, Stress-Related Diseases, and Coping, 3rd ed. New York: Henry Holt.

98. Peterson C, Seligman M, Vaillant G (1988) Pessimistic explanatory style is a risk factor for physical illness: a 35-year longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 55: 23–27.

99. Kubzansky L et al (2001) Is the glass half empty or half full? A prospective study of optimism and coronary heart disease in the normative ageing study. Psychosomatic Medicine 63: 910–16.

100. McCullough M et al (2000) Religious involvement and mortality: a meta-analytical review. Health Psychology 19: 211–22.

101. Frankl V (2004) Man’s Search for Meaning. London: Rider & Co.