Reality leaves a lot to the imagination.—Attributed to John Lennon

Exactly what constitutes the nature of ‘reality’ and the ‘meaning’ of life has preoccupied scientists, philosophers, and spiritual thinkers for much of our time on the planet. And even though you are unlikely to be consciously aware of the questions that inform almost every moment of your life, they are there, directing your emotions, needs, moods, desires, and behaviors: ‘What is happening to me?’ ‘Why do I feel this way?’ ‘What does it mean?’ ‘What should I do?’

At virtually every turn, and, often unconsciously, we ask questions and make decisions about our world and our place in it as we navigate through the complexity of daily living, based on the assumption that we understand, or can understand, what’s really ‘going on’.

For much of the time, this way of managing the world serves our needs. We eat, sleep, have sex, look to people and things we hope will give us something we call ‘happiness’. To many of us, the challenge seems to be to control the unruly, unpredictable, unreliable elements of life, thinking that somehow, some day, we’ll make it all fit. Sometimes it will seem to work; more often, it won’t.

Disappointment sets in, and we start all over again, trying to rearrange the pieces of an ever-changing puzzle. If it doesn’t, then we turn to an ‘expert’ in the particular part of our malfunctioning body-mind in the hope that she can help.

One of our problems as a species is that we use our superior ability to think, but seldom think about the way in which we think. Even less do we suspect that how we think directly affects our experience, happy or unhappy, functional or dysfunctional, sick or well.

This should not be confused either with New Age ‘positive thinking’ or the hunting down and challenging of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy’s ‘negative thinking patterns’. We are talking about the structure and process of thinking, believing and knowing—more epistemology and less psychology; more how and less why.

In order fully to understand what mainstream NLP means when it refers to ‘the structure of subjective experience’, try the following exercise:

Recall a pleasant experience from your past—perhaps a holiday, or a reunion with a loved one. Make sure it is a specific experience or event.

Now, ask yourself how you were thinking about the memory, how you remember what you were doing, and how you felt. Most people answer vaguely at first, ‘I just remember it was good’; ‘We had a good time’; ‘I was feeling great’.

Now, return to the memory and answer the following questions: How strongly can you re-create your good feelings by recalling the memory? Scale it from 1 (a little) to 10 (as if you were there right now).

Do you remember the experience as a picture? If so:

- Is it in color or black and white?

- Is it moving or still?

- Is it near or far away?

- Are you observing it as if on a screen, or through your own eyes?

Are there any sounds to the memory? If so, are they:

- Loud or soft?

- Words or music?

- Internal self-talk?

What feelings or sensations are involved, if any?

What other qualities do you notice? Think of all your senses: visual, auditory, kinesthetic (feeling), gustatory (taste), and olfactory (smell). Make a note of all these distinctions.

The experiment above demonstrates the following:

- your memory was created out of sensory-rich information (that is, you needed to activate, albeit internally, your senses of sight, hearing, feeling, and touch, and, perhaps taste and smell. We call these sensory modalities);

- by acting ‘as if’ you were there, you re-experienced some degree of feeling or emotion that corresponded with the feelings or emotions you experienced during the original scenario. This is what we call ‘state’—the sum total of the psychophysiological changes that take place when you remember, imagine, or experience a particular memory, behavior, or event;

- your senses had certain qualities: color, size, movement, degree of involvement, volume, temperature, etc (we call these sub-modalities, because they are subsidiary qualities of your sensory modalities); and

- you favored one sense over the others (we call this your sensory preference).

Additionally, even though you might have experienced strong feelings or emotions when recalling this experience, you also somehow ‘knew’ that you were ‘here’, remembering, and not actually back ‘there’.

A simple remembered incident from your past turns out to have a host of qualities that permits you to sort information, code it, and store it in a ‘filing system’ that allows you to distinguish one event from another, place it on an internal ‘time line’, and invest it with a unique emotional ‘charge’.

Now, try something else.

Imagine someone raking their fingernails down a blackboard (supposing you’re old enough to remember blackboards). What is your response?

Or, pretend you have a lemon in your hand. Feel the weight of it and the texture of the skin. See the color of the peel and the flesh in your mind’s eye. Hear the sound of the knife as you slice into it, and smell the pungent oil of the skin. Now bite into one half, and swill the juice around your mouth before swallowing it. Notice its sharpness, how it reacts with your taste buds and the enamel of your teeth.

If you did this vividly enough, you either winced at the sound of nails on the blackboard, or found your salivary glands going into overdrive. There is no real blackboard, no lemon. Just the power of your imagination; a part of your brain that is unable to distinguish between what is real and what is imaginary; a cascade of neurochemicals and a physical response.

The fact that people can activate physiological responses merely by imagining or remembering events will, as we will explain, serve an important function in the provision of healthcare (and contribute greatly to our own mental and physical health). By understanding more about how a patient ‘sets up’ and maintains his particular dysfunction, you will become more strategically positioned to develop practical interventions to empower him to move more systematically in the direction of self-regulation, health, and wellbeing.

One of the fundamental messages of NLP is: we act on our representation of the world, rather than on the world itself.

The original (and prescient) NLP model of cognition suggested that information gathered from the external world is filtered through our preferred sensory modalities, and then through the constraints of our neurology and our social and cultural conditioning. This contributes to the creation of the internal model of ‘reality’ by which we function. The degree to which data are filtered dictates how expanded or constrained the model—and, therefore, our experience—is.

Over recent years, we have gained a fuller idea of how the organs of perception work, thanks to developments in neuroscience, and the abiding curiosity of those scientists who keep inquiring into the mysteries of the ‘black box’ of consciousness.

Surprisingly, perhaps, perception (along with our ability to predict and plan) emerges from a cortical skin comprised of stacks of cells, each only six neurons deep. These stacks, known as cortical columns, are packed together and function in a complex, bi-directional relationship with each other. Each of your senses relies on cortical columns packed into different areas of the brain (vision in the occipital lobe at the back of the cortex; visualization in the central prefrontal area; hearing on either side of the temporal lobe; kinesthetics in the parietal lobe).

Whenever you experience something new, most powerfully as a child, information floods in from the brainstem, fountains up through the cortical stacks, creating the informational phenomenon known as ‘bottom-up’ processing. When unaffected by previous experience, this ‘pure’ consciousness is unlikely to be experienced by older children and adults, unless they practice some of the techniques of mindful awareness referred to elsewhere in this book (see Appendix A, pages 357 to 360).

As time passes and your databank of experience grows, this inflow of experience becomes subject to modification. As suggested by Bandler and Grinder, who referred to ‘neurological constraints’ (stored experiences, beliefs, cultural rules and injunctions, values, etc),121 information already held in the nervous system flows downwards (‘top-down’ processing). The collision of these two creates a synthesis of new and old—a kaleidoscope of experience and impressions. The way in which this synthesis resolves itself gives rise to what we have already referred to as ‘state’. State, in turn, directly impacts affect and behavior.

States are sometimes referred to as ‘neural networks’, ‘neural clusters’, or ‘neural pathways’. More colorful descriptions, such as ‘engrams’, ‘parts’, and ‘sub-personalities’122 are also sometimes applied, influenced, perhaps, by the way these behaviors often appear to function beyond the direct, conscious control of the host.

It has been suggested that states develop out of the brain’s tendency to simplify tasks, especially motor skills, but also behaviors, responses, and the feelings that arise out of these.

We all have states to facilitate many different ways of being in the world. When you enter your place of business, you also activate a specific ‘working state’. When you arrive home and are greeted by the kids, you step into your ‘domestic state’. Your states allow you to have various ways of being-in-the-world (strategies): for playing sports; dialing a cold call; making love; and eating in a restaurant. You probably also have states for worrying about the mortgage; fearing a tax audit; obsessing about an argument with your partner or spouse; and hanging out with your friends.

We usually define state as ‘the sum total of the psychophysiological changes that take place when you remember, imagine, or experience a particular memory, behavior or event’, or, ‘the integrated sum of mental, physical, and emotional conditions from which the subject is acting’.

Even more significant, though, are two qualities of states:

- Many of them function independently of other feelings and behaviors (we speak about them having defined ‘boundary conditions’);

- Once activated, the feelings, emotions, and/or behaviors coded into that particular state will tend to ‘run’, unless the pattern is somehow interrupted or replaced.

‘Reality’, then, is a construct of our neurology, in much the same way as ‘vision’ is an interpretation by the brain, rather than a literal reflection of the external world. It follows, therefore, that at best the map can only approximate the world or ‘territory’ it represents, not least because the territory is too complex to render in exact detail, and our maps, made up as they are from selective data uniquely filtered through personal sensory bias, differ to some extent or other from those of the people around us.

However, when we create an internal representation of the ‘outside’ world, we seldom question the accuracy or validity of that representation, or notice the differences between the maps of the people we meet.

Alfred Korzybski, the founder of the field of General Semantics, made the now-famous observation, ‘The map is not the territory’, and attributed what he called ‘un-sanity’ to the fact that we often fail to distinguish between the two.123

Acquiring access to the patient’s map to ascertain how her representation limits his world is one of the first skills the effective practitioner should acquire. The patient is unlikely to have conscious access to her internal processing, but information nevertheless ‘leaks’ in a number of ways, both verbal and non-verbal.

To gain insight into the patient’s situation, we need to identify her sensory preferences, how she codes the ‘meaning’ of her experience, and how she creates and maintains negative feelings and repetitive behaviors. With that information in hand, it becomes relatively easy to interrupt and change her experience by changing the structure that supports it.

The information that follows is generalized, and it is important to remember that some people may display idiosyncratic patterns. Observe carefully before making assumptions.

Decoding the patient’s inner experience

The speaker may reveal his or her sensory preference (or the pattern of the current experience) in one or other of the following ways:

- eye moments (‘eye accessing cues’) may be related to how information is stored in the brain and to innervation of the eye by four cranial nerves;

- choice of words, also known as ‘sensory predicates’;

- position and movement of the body; and

- tone, rate, and pitch of speech.

Eye movements

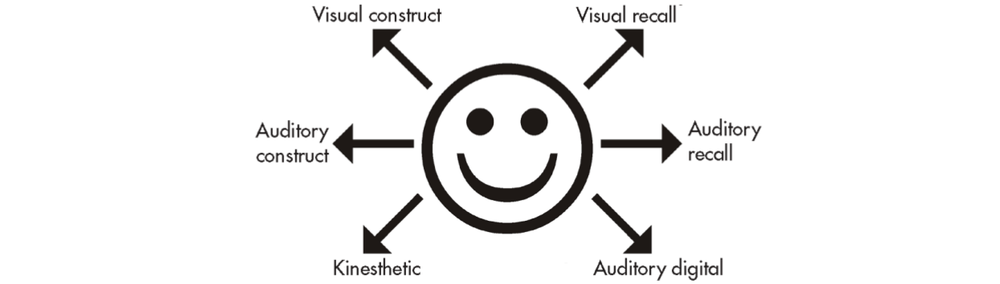

The classic NLP model suggests that most right-handed people look to the left when remembering events, and to the right when creating new images (Figure 6.1).

Visual processing is suggested when the subject looks upwards, to the left, right, or directly ahead, the vision slightly defocused.

Auditory access is indicated when the eyes are in the midline, more or less in line with the ears. The head is often tilted to one side, or it may be turned so that the listener’s dominant ear is nearest the speaker.

Self-talk (also known as ‘auditory digital’) is often indicated when the speaker looks down and to his left.

Internal kinesthetics (feelings/emotions) may be present when the subject looks down and to the right. It should be noted that olfactory and gustatory processing are usually included within the kinesthetic categorization.

Sensory predicates

Many words and phrases indicate a preference for one or other sensory modalities—for example:

Visual: ‘It looks clear to me’; ‘I get the picture’; ‘We need to focus on this’; ‘It’s too much in my face’.

Auditory: ‘I hear what you’re saying’; ‘That sounds good to me’; ‘I can’t hear myself think’.

Kinesthetic: ‘I really feel for you’; ‘You need to get a grip on yourself’; ‘Everything feels as if it’s getting on top of me’.

Posture and movement

Visual: Sitting and standing erect, with the head up. Gestures are high, often as if ‘sketching’ in important details. Tight muscle tonus.

Auditory: Neither upward reaching nor slumped. Gestures are slower and more measured.

Kinesthetic: Often slumped, as if dragged down. Muscle tonus is slack. Gestures are slow and asymmetrical.

Speech

Visual: The pitch is often higher than average, and the rate of speech rapid-fire. There is considerable variation in tone.

Auditory: Speech is somewhat slower, pitched in the mid-range and with less variation.

Kinesthetic: Speech is slow and measured, often lacking color or animation.

Some commentators have even suggested a correlation between physical build and sensory preference. The categories of the now largely discarded physical typology—ectomorph, mesomorph, and endomorph—are said to correspond to visual, auditory, and kinesthetic preferences.

Interestingly, many traditional health systems include physical-emotional categorizations similar to the visual-auditory-kinesthetic distinctions. The ancient Indian system of Ayurveda, for example, refers to prakruti, innate bio-psychological tendency, made up of different combinations of pitta, vata, and kapha, roughly corresponding to visual, auditory, and kinesthetic.

Sub-modalities: shades of meaning

But how can we be sure that something we remember actually happened? By what mechanism do we distinguish differences in the time, quality, intensity, and meaning of an experience?

Evolution has equipped us not only with senses by which we ‘sample’ the external world and make internal representations of what we see, hear, feel, smell, and taste, but each organ of perception also has specialized receptors that allow us to make distinctions that further drive the making of meaning.

The auditory input channel, for example, permits the reception of not only packets of data, but also qualities such as the direction from which a sound comes, the pitch and tonality of a voice, rhythm, direction, and a myriad of other qualities.

Visually, we are equipped to detect color, movement, patterns, and relationships between items within our visual field, distance, etc. Our kinesthetic senses permit physical touch, organ awareness, and inner ‘feelings’, each of which in turn may be subdivided into an almost infinite array of subtleties. Likewise, smell and taste have qualities dependent on the receptors inside our mouths and nasal passages.

Our internal representations, therefore, are assembled not simply out of varying arrays of modalities, but each modality is ‘tagged’ by one or more characteristics that keep it distinct from its associated modalities (Figure 6.2). Given the almost limitless combinations that five modalities and their attendant sub-modalities possess, we have a powerful methodology for storing and accessing information in a relatively organized way.

| Visual | Auditory | Kinesthetic |

| Associated/dissociated | Tonality | Location |

| Size | Volume | Movement (direction) |

| Location | Inside/outside head | Pressure/weight |

| Distance | Location | Extension (start- and end-points) |

| Color/black and white | Pitch | Temperature |

| Vivid/pastel | Tempo | Duration |

| 2D/3D | Continuous/interrupted | Intensity |

| Single/multiple images | Clear/diffuse | Shape |

| Flat or tilted | etc. | etc. |

| Transitions smooth/jumpy | ||

| etc. |

Changing the map

It follows that if sub-modality coding is part of how the perception-to-meaning transformation really works, changing the sub-modalities of an experience should, of necessity, change the meaning of that experience.

Recall the pleasant memory from the previous exercise and re-enter it as fully as possible. See in your mind’s eye what you saw then, hear what you heard, notice the feelings you felt. Recall any smells and tastes that might have been present. Refer to how you scored the intensity of the remembered experience.

Now slowly push the image away from you, or step back from it, so that you are seeing it as if from a distance.

Continue increasing the distance between you and the image. If you recalled the original image through your own eyes, pull back until you see yourself in the scene as if on a screen or in a photograph. Drain out any color. Let the details diminish, as the image moves further from you.

Rescale the emotional intensity and compare it with the first time you calibrated it.

The majority of people who do this experiment find that feelings of pleasure are substantially diminished. Experiment by changing other sub-modalities. If you favor auditory or kinesthetic modalities over the visual, you might have to experiment with changing or turning down any sounds or sensations within the experience to notice an effect. You may also have observed that changing just one sub-modality triggered a domino effect on the others. This is what is known as the ‘driver’ sub-modality—the single shift that alters the entire Gestalt.

As a general rule, large, bright, close, and colorful images usually intensify feelings, whereas smaller, distant, less distinct, and colorless imagery reduces emotional impact. Association (seeing through the subject’s eyes) commonly amplifies responses, while dissociation (seeing the self as if in a picture or movie) decreases them.

Remember to restore the original sub-modalities to your experience before moving on.

Eliciting sub-modalities

Quite simply, ask. Ask, ‘How do you do that?’; ‘What happens when you think of that?’; ‘Where in your body is your (symptom)? If it had a color (shape, size, weight, etc), what would it be?’. Take your time, and guard against being drawn back into ‘content’. You are eliciting the structure of the experience, its component building blocks, not its ‘story’.

Applying sub-modality change in practice

Simple issues can be resolved with sub-modality changes, literally within a few minutes. Since each person’s unique coding system is the basis of his sense of reality, work systematically and ecologically, changing one sub-modality at a time, putting it back if no change takes place before moving on to the next. Ideally, you will find the one sub-modality that triggers a system-wide change.

Case history: The patient, a 66-year-old retired painter and decorator, had a six-month history of mounting anxiety. He was having difficulty sleeping and asked for sleeping tablets. He said he had found life difficult since retiring. He had to look after his wife, his house, and his health, and worried about his ability to cope. A few weeks before the consultation, his roof had begun to leak, and he said his anxiety was stopping him doing anything to fix it—and this, in turn, was further exacerbating his anxiety.

After carefully pacing the patient in order to lower his anxiety, the practitioner asked him to describe his ‘anxiety’ in terms of its location, size, color, etc.

The patient said it was in his abdomen, ‘black’, and spherical, ‘like a ball’. He rated his level of discomfort at 7, with 10 being the worst anxiety possible. The practitioner and patient then began changing the qualities of the ball, pushing it further back, changing the color, size, etc. After a few minutes, he found to his great surprise that his rating had dropped to 3. The practitioner ended the consultation by asking him to practice this ‘relaxation technique’ of changing the sub-modalities of his anxiety whenever necessary.

The patient returned two weeks later saying he didn’t understand exactly what had happened, but ‘for some reason’ he felt much calmer and more relaxed, no longer wanted sleeping tablets, and was planning to sort out his leaking roof.

The initial consultation, the practitioner report, took no more than 10 minutes, including history-taking and outcome-planning. Notice in the above example that at no time did the practitioner offer advice or argumentation to challenge the patient’s world-view. Rather than suggest he change his self-defeating self-talk, she moved to another level: that of the structure of the patient’s model, which she then helped him change.

Especially where more complex problems are concerned, bear in mind that how the patient describes his problem differs substantially from how the problem actually functions. This follows from the way in which we, both consciously and unconsciously, edit information in order to reduce it to more manageable proportions.

George Miller calculated that we are only able consciously to process between five and seven ‘bits’ of information at a time.124 More than that and details tend to be lost to both short- and long-term memory.

However, what is left out or transformed in the process of creating our models of the world is as important as what is left in. The transformation of direct, subjective experience (Deep Structure) into what is communicated (Surface Structure) is governed by three processes: deletion, distortion, and generalization:

- Deletion is the filtering of data to reduce it to levels we can handle. This, in part, explains why patients forget between 40% and 80% of medical information provided by healthcare practitioners within minutes of leaving the consultation.125

- Distortion is the inevitable consequence of selection. Jumping to conclusions, ‘catasrophizing’, ‘remembering’ something that wasn’t actually said, are all examples of distortion.

- Generalization is an inbuilt human skill that allows us to predict events from what has gone before. However, when only one or two elements of an experience become generalized to ‘all’ similar events, problems can ensue. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a generalized response to traumatic events such as childhood abuse or car accidents.

NLP’s Meta Model (see The Structure of Magic, http://www.amazon.com/s/ref=nb_sb_noss?url=search-alias%3Daps&field-keywords=The+Structure+of+Magic) defines several distinctions within each category and provides specific tools by which deletions, distortions, and generalizations can be challenged. It is, however, useful, when gathering information, to favor questions starting with how, where, when, with whom, how often, etc, all of which provide grounded, fact-based data, rather than asking ‘why?’, which often elicits speculation, justification, and defensive behavior. We expand on the art of gathering quality data in a later chapter.

EXERCISES

Building skill sets

Work with just one component at a time; take a day or two for each. This eliminates confusion. Practice consistently in the beginning to identify, rather than act on, what you observe.

1. Listen for sensory predicates, identifying the subject’s preferred mode. (Be aware that many patients may present kinesthetically, simply because they are experiencing somatic distress; their preferred modality may, in fact, be different.)

2. Watch for eye accessing cues. Calibrate eye position with the emotional content of the subject’s account.

3. Elicit sub-modality distinctions of the problem states.

4. Experiment with changing them and note the effect.

Note: To avoid ‘performance anxiety’ with your subject and to inoculate against ‘failure’, use phrases such as: ‘Just before we begin, let’s try a little experiment’, or ‘I just need to find something out.’ When coaching sub-modality changes, it often helps to use examples and analogies to explain the process. Referring to the controls of a TV set or sound system is one way of doing this.

Notes

121. Bandler R, Grinder J (1975) The Structure of Magic, Palo Alto, CA: Science and Behavior Books.

122. Bradshaw J (1996, 3rd ed.) The Family: A Revolutionary Way of Self-Discovery. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications.

123. Korzybski A (1933; 1994) Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics. Englewood, NJ: Institute of General Semantics.

124. Miller GA (1956) The magical number seven, plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review 63: 81–97.

125. McGuire IC (1996) Remembering what the doctor said: organization and older adults’ memory. Experimental Ageing Research 22: 403–28.