It is possible to believe that all the human mind has ever accomplished is but the dream before the awakening.—H.G. Wells

More than 30 years ago, the creators and developers of NLP could only speculate how many of the techniques they were using empirically could actually work. How was it possible that some people could free themselves from a long-standing phobia, allergy or trauma—sometimes in a matter of a few minutes?

Up until then, psychological change, we were led to believe, was possible, but only with considerable time and effort. Even today, the ‘brief’ cognitive therapies require upwards of eight sessions, and success often needs to be boosted with psychotropic drugs. However, research from the frontiers of brain science reveals that the belief that neuronal function can only be affected pharmacologically and/or with considerable psychological effort is questionable.

The key is the capability of the brain called neuroplasticity.

A few decades back, it was widely believed that the brain was a closed, machine-like system, functioning only within the boundaries of its genetic heritage. The neuronal patterns we started out with were the neuronal patterns we died with—give or take the ones we lost along the way to the ravages of time.

But the brain, as we are looking into it in the 21st century, is a very different affair. We know now that it co-creates our ‘reality’ according to past experiences and present events.

We can recognize how its moods and memories resonate in every cell of our bodies. We are beginning to realize that it mediates the way our bodies store and communicate the emotional assaults we experience.273 Added to that is an extraordinary ability to invent internal realities that can have as big an impact on our health and wellbeing as an external trauma or a germ or a gene. We have even come to suspect, through the new science of epigenetics, that it helps us hold our DNA in trust for later generations—for, if we drink, or smoke, or stress too much274 (or, conversely, alter the length of our telomeres by meditating regularly275), we may pass the consequences on to our descendants for centuries to come.

Above all—and, this is probably the brain’s most extraordinary quality—it is the only organism that we know of anywhere in the universe that has the capacity to evolve itself. By an experience, an act of imagination or learning, people can create a psychophysical reality that is more (or less) capable, resourceful, and healthier than the one they had a day, or a month or a year before.276

Repatterning, in the Medical NLP model, may be seen as a protocol that is aimed first at the neurological/experiential stratum, and then at the levels of behavior and its evaluation. This takes place in two main stages: the first, deconstructing and replacing the dysfunctional pattern with a more useful and appropriate response or behavior; and the second, applying conditioning techniques (future-pacing) to accustom the patient, both cognitively and neurologically, to the changes it is hoped she will enjoy in her post-treatment life.

In order to understand better how the techniques we present below are structured, it should be recalled that most Medical NLP techniques rely on:

- dissociation;

- repatterning;

- re-association; and

- collapsing anchors.

Future-pacing and why it works

For many years, ‘visualization’ and other imaginal techniques were regarded as likely to have minimal effect on real-world functioning. Its popularity among followers of ‘New Age’ complementary therapies increased suspicion among many mainstream scientists, even though there were indications that it could be an effective supplementary approach to enhancing sports performance.277

This is changing and for good reason. It works.

Think of the number three for a moment. Imagine it written up on a surface inside your head. As you do that, your visual cortex lights up exactly as if you were seeing the same digit. Now, imagine picking up a heavy barbell and begin to perform a series of curls—the same exercise you might do with free weights at a gym. Hear your personal trainer urging you on. Imagine (without actually moving your body), that your bicep is beginning to tire; lactic acid is burning like hot wires. The weight seems to be getting heavier…

Experiments show that if you did this regularly enough with full absorption, your muscles would actually get stronger—only 8% less than if you had actually done the exercise.278

For some years now, scientists, including V.S. Ramachandran, have used a device called a ‘mirror box’ to treat problems such as phantom limb pain, reflex sympathetic dystrophy pain (chronic pain persisting long after an injury has healed), and ‘learned’ pain. The mirror box works by reflecting an image of a healthy limb onto its wasted or absent counterpart.

The illusion ‘rewires’ the patient’s neurology to facilitate improvement or recovery from his physical condition.

A problem encountered with mirror box therapy is that the longer the pain has persisted, the less effective treatment is likely to be. However, Australian scientist G.L. Moseley demonstrated that patients who were taught to simply imagine moving their injured limb reduced or completely eliminated their pain.279

Future-pacing—a form of conditioning—then, incorporates the imaginal capabilities of the mind, together with practical application of the new behavior pattern, wherever possible. It is important, when designing an intervention, that the patient’s response to both thinking about the problem, as well as his actual real-world experience, is tested (using the SMC Scale, if appropriate).

After intervention and future-pacing, patients should be encouraged to resume their normal (or their new) activities as soon as possible and report back for readjustment or reinforcement, if required. (A useful injunction is, ‘I’d like you to go back and notice specifically what’s different and better so we can talk about that next time.’)

Despite the simplified NLP model of internal processing outlined earlier, we do not mean to suggest that each sense is entirely localized in its own area of the brain.

The work of Harvard Medical School’s Alvaro Pascual-Leone has confirmed considerable cortical overlap between senses and has demonstrated that various ‘operators’ organize sensory data from different sources in order to create experience. These operators are in constant competition to process signals effectively, depending on both the significance and the context of the signal.280

Designing a future-pace

Rule 1: Ensure that it is fully represented in all sensory modalities, in as much detail as possible.

Rule 2: It should meet all the requirements of well-formedness. It must also be attractive and relevant to the patient and his model—not that of the practitioner.

Rule 3: A future-pace for an ongoing response or behavior (for example, exercising three times a week, or following a specific eating plan) should be dissociated. This is thought to prompt the brain to continually move to ‘close the gap’, facilitating maintenance.

Rule 4: A new state (for example, being a non-smoker) should be represented as associated, in order to ‘lock in’ a discrete condition with clear boundary conditions.

Rule 5: The new state, response, or behavior should be placed on the patient’s time line. If necessary, create a means of metaphorically locking it in place.

Rule 6: After the patient has been future-paced, she should be fully reassociated, together with her new pattern(s), using suggestions to ‘float back above your future road or pathway, bringing into the present all the experiences, learnings, and resources from your new future, and drop down into your own body so that you can fully own and apply everything you’ve learned now as you get ready to move on from here into the future…’ etc (note the hypnotic language).

Before applying any of the patterns below, ensure that:

- the patient’s time line has been adjusted, with past events (including the problem) ‘behind’ her, but not hidden; and

- the agreed outcome/direction is well formed in all sensory modalities and placed on her future time line, a little in front of her.

Note: All interventions are designed to be completed within a single session. Do not attempt to carry a pattern over from one consultation to the next. Interventions should be executed rapidly to ensure pattern recognition by the brain. Repeat until automated.

Remember to apply the Subjective Measure of Comfort Scale before and after each intervention.

The patterns

Re-storying the narrative

Elsewhere in this book (see pages 162 and 163), we report how the act of story-telling helps put the patient’s experience into a form that makes sense to her. Writing down or delivering a narrative version of illness—the patient’s ‘pathography’—is, in itself, a therapeutic act. However, sometimes the practitioner can assist the patient by helping her to re-create her narrative. In this way, and working together, patient and practitioner can arrive at a more resourceful, and, often healthier, conclusion.

This process differs from the well-known Ericksonian technique of isomorphic metaphor. The latter is an entirely practitioner-centered approach, in which a story is created that parallels the problem condition, but with a resolution that suggests a new perspective and behavior to the patient.

Re-storying is, quite literally, a re-writing of history…at least, the history as it is remembered and re-presented by the patient. In order to do this, the patient and practitioner in partnership need to identify the ‘theme’ of the patient’s pathography, and then locate the point in the narrative where the story becomes problematical. The challenge then is to decide on a replacement theme, or a more useful resolution. This is largely an exercise in re-framing, so the practitioner needs to consider whether the content or the context of the patient’s experience needs to be changed (see Framing and Reframing, in Chapter 13, pages 177 to 180).

Very often, exploring the possible ‘positive intention’ of the symptom or condition will suggest a way forward.

Case history: A young woman, extremely ambitious and hard-working, had become hypothyroidal, and sought help to lose weight and regain her energy.

Her story was one of fear—mainly that she would lose clients and her standard of living if she didn’t work the long and tiring hours she believed were necessary. She had stopped all recreational activities, and it had been some years since she had taken a holiday. However, since she had already proved resistant to ‘taking it easy’ when it had been suggested to her by her primary care physician, the practitioner suggested re-storying her narrative.

He reviewed the patient’s written pathography, noting, as he did so, that negative-affect words far outweighed their positive counterparts, suggesting the patient had been unable even to imagine a way out of her impasse.

The practitioner explained the Medical NLP model of the ‘well-intentioned disease’, then asked her, ‘What do you regard as your biggest problem, aside from the thyroid trouble itself?’

Instantly, she said, ‘I know I work too hard—but I have to.’

‘And, what does hypothyroidism do for you?’

‘It slows me down.’

The practitioner said nothing, and simply waited for the patient’s response. It was a few seconds coming, then surprise flooded her face. When other people told her to slow down, she said, she felt immediately resistant. They just didn’t understand. ‘But, when my body told me in such an eloquent way, I suddenly realized I had to listen,’ she said.

The remainder of the re-storying involved exploring meditation, dietary options, regular check-ups, and a simple program of activity designed to create, rather than deplete, energy.

Simple scramble pattern

The scramble pattern may be used alone to change simple behaviors and responses.

It may also be used adjunctively, with other patterns, to disrupt more complex constellations of problems.

The principle is simply to interrupt a sequence by repeatedly ‘scrambling’ its component parts. A scrambled pattern should always be replaced with an alternative response to reduce the possibility of relapse.

Identify and number four or five distinct steps in the patient’s process. For example: (1) ‘I notice people watching me’; (2) ‘I begin to breathe erratically’; (3) ‘I feel my cheeks becoming warm’; (4) ‘I think, “I know they’ve noticed what’s happening”’; (5) ‘I start to blush.’

Starting with the original sequence, coach the patient into experiencing each step, using its number as a cue.

Begin to call out the numbers in different orders, increasing the speed as you go.

After six to eight cycles, stop and test.

If the unwanted response is not extinguished, repeat, ensuring that the patient is fully associated into each step as you call out its number.

Full sensory scramble

- Have the patient associate into and hold the negative kinesthetic as strongly as possible.

- Using a pen or your finger, have the patient follow with her eyes (without moving her head) through all eye-accessing positions in rapid succession. Ensure she tries to maintain the kinesthetic at its highest level throughout.

- Increase the speed, and randomize the movements.

- Continue for 60–90 seconds, change state, and then test.

- Repeat, if necessary, until the negative kinesthetic has been substantially reduced.

- Future-pace.

Visual-kinesthetic dissociation (fast phobia cure)

Visual-kinesthetic dissociation is the earliest, and one of the most commonly applied, techniques developed by the founders of NLP. It can be used to treat simple phobias, including ‘social phobia’, fear of public speaking, etc. It can also be incorporated in more complex protocols, as shown below. This version incorporates a final step (essentially a future-pace).

Note: Where the patient may have an extreme response to accessing thoughts about the trigger event or object, it is important to ensure she is ‘double-dissociated’ (that is, she is watching herself watching her dissociated self carrying out the procedure, rather than watching the procedure herself).

- Instruct her to ‘step out of, or float up from, your body, so you are watching yourself from a safe distance, watching the events. You don’t have to watch the events yourself.’ Ensure the patient is fully relaxed, and anchor the state in case you need to bring her back into a calm and more resourceful state.

- Have the patient imagine sitting in a movie theater, with a small, white screen placed in front of her and a little above eye level. On the screen is a small, still, monochrome picture of a moment or two before the sensitizing event that led to her phobic response (Safe Place 1).

- Instruct her to imagine creating a movie containing ‘all the experiences, responses and feelings you have had about this problem’. Reassure her that the movie, when it is run, will be small, distant and in black-and-white, and when it is complete, the screen will ‘white out’ (Safe Place 2).

- Have her float out of his body and up, into a position from which she can both observe herself and control the running of her movie.

- Instruct her to switch on the projector and run the sequence from Safe Place 1 to Safe Place 2 very rapidly, allowing the screen to white out when it is finished.

- Have her float down into her body and then step up into the white screen at the end of her movie.

- Turn on all the colors and sounds, and have her rewind the movie, experiencing events and sounds, associated, in reverse order until she emerges in Safe Place 1.

- Have her return to her seat and repeat steps 3 through 7, from three to five times, before testing. Notice that the final step is always run through from end to beginning (Safe Place 2 to Safe Place 1).

- Keep testing, and when the phobic response has been substantially reduced (to a 1 or a 2 on the SMC scale), you can begin the second part of the intervention.

Future-pace as follows:

- Sitting back in her seat, the patient expands the screen until it extends to the edges of her peripheral visual field.

- Have her create a full-color, richly detailed movie of her coping resourcefully in the situation that previously triggered the phobic response. Suggest she incorporates a soundtrack comprising music that she finds particularly uplifting.

- When she is satisfied with the movie and its soundtrack, have her run it (dissociated) from beginning to end, two or three times, each time starting at the beginning.

- Then, she can step into the movie (associated) and run it ‘as if’ she were actually experiencing this reality now. With her permission, you may also hold the safety anchor you set at the beginning of the intervention.

- Suggest she takes a few moments to run the resource movie several times, making sure she always starts at the beginning, until she is satisfied that everything she sees, hears, and, now, feels will support her in coping positively from now on. Reinforce with presuppositions and embedded commands to take on this new pattern as a permanent response.

V-K Dissociation is a powerful and useful technique. However, we caution against its indiscriminate application. Sometimes phobias serve an important purpose and disruption, without taking ecology into consideration, could be detrimental to the subject, as the example below illustrates.

Case history: The subject, a leading consultant pediatrician with a disabling fear of spiders, volunteered for treatment on one of our training courses. He believed his fear arose from waking up on two occasions to find large spiders on his pillow when he was a child in Africa.

However, when the trainer probed further, the subject recalled a further incident in which his baby sister was bitten by a spider and went into anaphylactic shock. He became markedly distressed at recalling his fear at being so powerless to help his sister. Even though he was only five years old at the time, he felt guilt at not having been able to ‘do something’ for his sister (who, happily, survived).

The trainer asked how that experience might have served a positive purpose in his later life, and the subject promptly replied, ‘Now I can cure anaphylactic shock in babies.’ This suggested his childhood feelings of helplessness had contributed to his choosing to be a doctor.

Mindful that a simple ‘blow-out’ of the phobia might impact the subject’s career, the trainer abandoned his plan to demonstrate the V-K Dissociation Pattern, and elected instead to apply a different intervention to resolve traumatic events, described below, in order to preserve all ecological considerations, while still resolving the disabling fear of spiders.

The advanced Medical NLP swish pattern

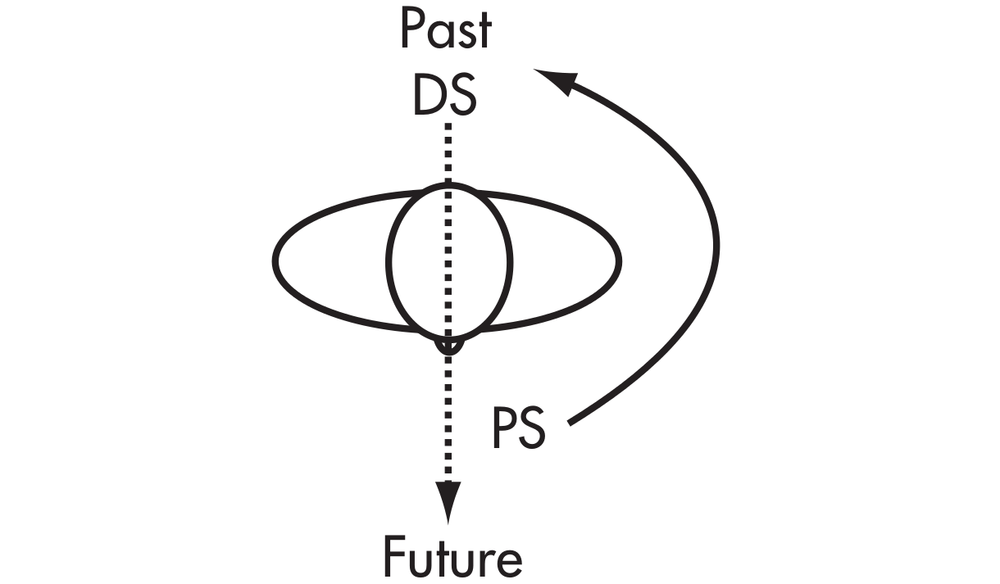

The version of the swish pattern outlined below is unique to Medical NLP and has the added value of automatically placing the problem-state (PS) on to the patient’s past time line.

- Check that the PS is in the position it naturally occurs in, in the patient’s internal representation.

- Place the desired-state (DS) directly behind her.

- Simultaneously, send the PS around her on to her past time line, while bringing the DS directly through her body into the position previously occupied by the PS. As this happens encourage her to create a strong kinesthetic of the DS moving through her body (see Figure 21.1).

Figure 21.1 The Medical NLP swish pattern

Other variations include:

- putting the DS far out on the patient’s horizon line with the PS in whatever position it naturally occupies, and then rapidly reversing the positions of the two states; and

- concealing the DS behind the PS, and then opening up a window in the center of the PS and rapidly expanding it so that the DS pops through.

Note: Although the swish pattern as outlined above relies on a visual lead, both auditory and kinesthetic swishes can be designed, following the same principles.

Resolving internal conflict

Internal conflict is often marked linguistically: ‘Part of me wants to [X], but another part wants [Y]’, or, ‘On the one hand I [X], but on the other I [Y]’). Sometimes the patient will ‘mark out’ different parts, gesturing to one side of his body and then to the other. We suspect this may reflect opposing hemispheric activity. Also, be aware that New Age self-diagnoses such as, ‘I always sabotage myself’, or ‘I have a fear of success/failure’ often indicate internal conflict.

- Explain that the parts are often set up at different times in the patient’s life and have therefore developed differing approaches to trying to meet her perceived needs, even though both are motivated by a shared positive intention.

- Externalize each part, together with all its characteristics (dissociation). This may be accomplished by having the patient extend both hands, palms uppermost, and ‘place’ one part in each. Suggest, ‘Each hand now holds a part with all its beliefs, behaviors and qualities.’ Have the patient code the totality of each part with a distinctive color.

- Chunk each in turn to find shared positive intention (see Chapter 12).

- Point out that, since both parts have a shared positive intention, they can cooperate in creating a range of possible new responses that will allow the patient to have more appropriate responses.

- Have her describe the ‘positive traits’ of each part—for example, one might be ‘creative’, the other ‘reliable’.

- Ask how each part could benefit by sharing some of the qualities of the other—for example, creativity could be more reliable rather than sporadic, while reliability could be helped to ‘loosen up’ with a bit of creativity.

- When the patient has found the ‘middle ground’, have her fix her attention on the space between her hands and begin to float them together, eventually blending the two colors to represent the new ‘third’ state. Reassure both parts that the intention is not to eliminate them (they might be needed in a specific context), but to widen their range of responses.

- Have the patient bring her hands towards her body and imagine the new color and all its qualities flowing into her body and life (re-association). Give lots of hypnotic suggestions presupposing more choices and a wider range of responses.

- Future-pace new potential responses, and test this by having the patient think of how she could respond to situations that previously caused her problems.

Resolving trauma

Important note: The treatment of serious traumatic events, such as severe physical or sexual abuse, should not be attempted without adequate training. See the Resources section for specialized workshop training.

Trauma—often long-forgotten, and including childhood abuse and neglect—is coming under increasing suspicion as a major factor for the later development of a wide range of medically unexplained conditions, including many involving chronic pain.281 Compelling neurophysiological evidence is emerging that the patient suffering from extreme ‘overwhelm’ can become locked into a self-perpetuating cycle of psychological arousal, undischarged ‘freeze’ state and actual physiological changes.

Because of the down-regulation of the frontal cortex, the patient’s inability logically to process the ‘reality’ of the threat profoundly affects his capacity to break out of the condition. One significant effect is that his response to ‘time’ becomes dislocated. In the words of behavioral neurologist Robert C. Scaer, the sufferer is caught up in past events, unable to relate to present events, and oblivious to the future, except to the perceived threat of pain or annihilation.282

The treatment of ‘functional’ disorders caused, or exacerbated by, trauma (if they are diagnosed) is currently heavily slewed towards symptomatic relief by pharmacological means (blocking the kinesthetic) and/or some form of ‘talking cure’, often encouraging the patient to challenge or deny the devastating effect of his thoughts and feelings.

Both these approaches, in one way or another, deny the somatic ‘reality’ of the patient’s experience. And, in seeking to have the patient do the same, they not only inadvertently disregard the patient’s somatic experience as a ‘doorway’ to his internal map, but attempt to brick up an opening to integration, healing, and health.

The ability to perceive, find meaning in, and act upon the felt sense has been demonstrated to have powerful clinical application in a wide range of medical conditions, including migraine; vertigo; hypertension; and immune disorders, such as multiple sclerosis, arthritis, and cancer.283

The patterns below seek to integrate what we know so far about the patient’s relation to time, his ability to reconnect with the frontal cortex, the importance of meaning and metaphor and, above all, the validity of his somatic response.

The affect bridge

Affect bridging is a technique designed to identify events perceived as causal. We do not automatically accept these revelations as ‘real’, but regard them as part of the patient’s model, and therefore potentially useful in restructuring the maladaptive behavior or response.

Note: We advise caution in setting up an affect bridge to avoid associating the patient into a deeply disturbing event. Therefore, our instructions should always include suggestions that she ‘go back as your adult self, and observe from a safe place, as if on a television or movie screen’. This minimizes the risk of full abreaction and possible retraumatization.

- Have the patient fully experience the somatic response to the problem state and anchor when the experience is at its height.

- Hold the anchor and instruct the patient to ‘follow the feeling back to the first time you felt this way’.

- Release the anchor as soon as the patient identifies the source and, if necessary, have her dissociate as described in the note above.

Case study: The patient, aged 27, had problems eating anything but soft food, such as scrambled eggs and porridge.

His gag response was anchored and bridged back to a long-forgotten incident in which, as a small child, he had choked and lost consciousness while eating bananas and custard. (This is a simple, clear example of the symptom—gagging—acting as a solution to, or protection from, the patient’s underlying problem. See Chapter 12, pages 159 to 172.) The intervention described on the following page was applied.

Changing responses to past experiences

The severity of traumatization is often associated with the subject’s perceived loss of control at the time of the trauma. Therefore, this pattern depends on accessing and stacking strong coping resources. Although the number of steps involved may seem daunting at first, there is a logical structure which, when mastered, allows for improvisation and adaptation.

Have the subject identify the traumatic event. Do not immerse yourself or him in unnecessary detail. Reassure him that ‘while we can’t change what happened, we can change our response to what happened’ (this paces the patient’s belief or experience about the gravity of the experience, while opening him to hope about his ability to change).

- Return him to his present, ‘more adult’, associated self and explore the resources by which the ‘past self’ would have been able better to cope had he had them at the time of the trauma. Have the subject convert the resources into a symbol—for example, a color or a light.

- ‘Send’ the resources back down the past time line to the younger self, and then have the subject move rapidly over the past time line to associate into the body of the younger self in time to receive the resources ‘from the future’. Test by asking the subject how he would feel differently or better with these resources. When satisfied, have him ‘keep those feelings’ and return to his present, adult self.

- Send the adult self back as an observer to watch and report on how the traumatizing incident would have played out differently when the subject had the means better to cope.

- If any anger, frustration, fear, etc persists, especially where a significant other was responsible for the trauma, give the subject permission ‘in the privacy of your own mind’ to say, do or feel whatever was not said, done, or felt at the time. You may observe considerable activity, physical, and emotional, during this phase. Remain engaged and wait until the process is complete. Dissipation of the freeze state may express itself as ‘silent abreaction’ (usually gentle weeping)—a positive development, calmly to be supported.

- Have the adult self associate into the scenario and reassure the younger self that he is safe and will survive, overcome, and flourish now.

- Have the subject step out and associate into his younger self and receive that information he was lacking at the time.

- The subject then steps back out into his adult self, and re-associates with his newly resourced younger self by drawing him back into his (adult) body.

- Use hypnotic language. An example: ‘Now, with all the resources you have given your younger self, combined with the greater knowledge and experience of your adult self to protect it, rapidly travel back up the past towards the present, allowing your unconscious to transform, recode, and reorganize all your past experiences in the light of these new understandings.’ Use multiple injunctions to reinforce the effect.

- When the subject reaches the present, he stops and watches himself moving into the future. Encourage him to notice and report how his responses, behaviors, and feelings are now in the light of the ‘new’ past experiences.

- Have him travel right to the end of the future time line, and then float up and back, and re-associate into his body, integrating all the resources and experiences from both past and future for use from the present moment on.

- Repeat this several times, floating back to before the traumatic event (with all the positive resources), up the past time line to the present, and then as in step 9, into the future. Anchor in the full-sensory representation of present comfort and optimism and future self-efficacy.

- Test for responses to past event. If some distress persists, repeat the process or layer work with other principles, such as V-K Dissociation, reframing, collapsing anchors, etc.

Note: This pattern may be used ‘content-free’—that is, without explicit knowledge or revelation of the original traumatic event. If the patient shows reluctance, acknowledge his need for privacy, and simply proceed with reference to ‘the original situation or event’.

Metaphoric transformation

Metaphoric transformation resembles the previous pattern, with one important exception: the use of patient-generated metaphors and memories to drive change. Do not necessarily expect to ‘understand’ how the metaphor is relevant to the patient’s subjective experience; by definition, it represents something much more extensive and encompassing than its surface appearance.

- Prepare the patient by explaining the principle of ‘unconscious association’; tell him that the unconscious mind makes many connections and will present those which are particularly relevant at this time.

- Have him fully associate into the kinesthetic of the problem state.

- Ask him for his earliest memory. We’re not asking him to speculate on the ‘cause’ of his problem, but simply to move back into the very earliest memory he can retrieve.

- When he does that, suggest his unconscious mind has presented a specific memory as a metaphor (an image, symbol, or other spontaneous representation). This functions either to identify the ‘cause’ of the problem, or to suggest a solution.

- Ask, ‘If you could, or, if you needed to, how would you prefer to remember this in a way that will help you deal differently and better with the problem you have been having?’

- Assist the patient in designing a new, more useful memory.

- Anchor his responses, and then follow steps 9 through 11 as outlined in the previous pattern.

Case history: The patient, in his early 40s, presented with symptoms of extreme allostatic load, and revealed that he had been ‘compulsively’ unfaithful to his wife.

When she found out, their relationship came under extreme strain. He suggested he was drawn to other women as ‘a kind of mother substitute’, since he had grown up with a punitive mother and no father. His earliest memory was of being trapped inside with his mother, trying desperately to get out to the safety of his grandmother’s house. The door was locked. When asked how he would like to change the memory, he said instantly, ‘I don’t want to leave my mother. I just want to know the door can open.’ He made the change to the memory, completed the intervention, and reported experiencing an overwhelming sense of optimism and peace.

The alternative reality pattern

This, esoteric sounding, pattern emerged from an extended conversation with a physicist—who was suffering from a knee injury that had resisted treatment—about the theories of alternative realities and the unreliability of memory.

The former proposes an infinite number of potential realities, only one of which materializes when a specific action is taken, and the latter is based on recent research suggesting that memories are ‘reconstructed’ each time we access them.284 The pattern has subsequently proved useful in a wide range of situations, both as a stand-alone intervention and adjunctively with other treatments. When introducing the concept of alternative realities, it may be useful to refer to several popular films, such as Sliding Doors and The Matrix, which explore the theme.

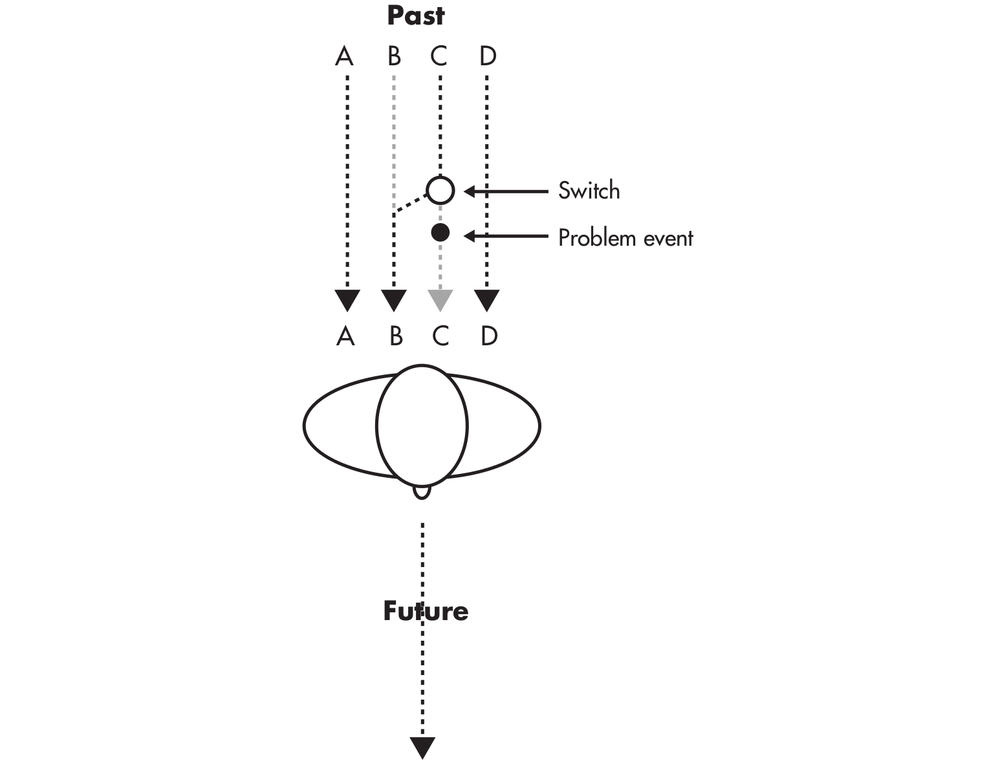

- Set up in parallel formation several ‘potential’ past time lines, including one that incorporates the accident or incident perceived as having caused the problem (Figure 21.2).

- Have the patient float up and over the causal incident and back down on to that time line some considerable distance before the event.

- Set up a ‘switch’ (the analogy of the rail switches used to divert trains onto another line is useful) just before the problem event.

- Select an alternative line that events can switch to instead of following the old route through the problem event and beyond. Elicit as much detail as possible about the chosen alternative reality.

- Have the patient move rapidly up the old reality, then switch to the new version, and on.

- Repeat this at least five times, and then test.

Figure 21.2 The alternative reality pattern (seen from above). Instead of running from C to C and into the future, this pattern diverts the past at the switch, just before the problem event, to the ‘alternative reality’: C to B.

Dealing with multiple conditions

Patients will sometimes present with several loosely related problems. The practitioner’s options are as follows:

Have the patient arrange the problems in order of importance and suggest starting with the most important one, leaving the others for further consultations.

Suggest you both explore all the problems for any underlying or common factors. This process utilizes chunking and reframing.

- Write a brief description of each problem in its own column.

- Chunk each in turn for its positive intention. Ensure this is a core issue—that is, that the patient is unable to proceed any further.

- Find the commonalities that all the problems share.

- Chunk and/or reframe until a single, shared intention is identified.

- Select the appropriate intervention and apply.

- Test to ensure that changes are reflected in each problem area. Ensure that the core change generalizes out into all.

- Future-pace each outcome individually.

- Test again to ensure the appropriate changes have been made.

Case history: The patient was clinically obese, and his knee pain was so intense that he could only walk with sticks. He complained that he was bored, had lost all interest in life, and, while he knew he had to change his diet, was unable to find the motivation to do so. He also felt his wife was becoming increasingly distant, and he worried that she might leave him. Together, the practitioner and the patient agreed that: (1) his eating was seeking to buffer him against his general feelings of malaise; (2) his lack of motivation protected him from failure; and (3) his wife’s apparent withdrawal could mean she didn’t want to add to his problems, not necessarily that she wished to leave him.

All three intentions were reframed in positive terms: (1) feeling good; (2) succeeding in his efforts; and (3) re-engaging with his wife. In exploring for commonalities, the practitioner asked, ‘When you’ve become slimmer and fitter [the presupposition here is that he would become slimmer and fitter, not that he might do so], what will you be doing that these problems have prevented you from even considering until now?’ (This last question prompted a spontaneous chunking process and the patient identified a commonality he believed all his problems shared.)

The man looked down at the floor and began to cry softly. He said, ‘We used to take lovely walks in the countryside. I really want to do that again.’

When the man had dissipated enough distress to allow him to resume, the practitioner redirected the patient towards a plan that would gradually reduce his intake of food and increase his activity.

He was instructed to seek out his wife’s help maintaining his lifestyle changes, and planning walks in the country.

The patient started to leave in buoyant mood, excited about ‘getting my life back again’ and anxious to speak to his wife. When he was at the door, the practitioner called him back—to hand him the sticks he’d forgotten at the side of his chair.

The challenge of ‘Yes’

The following pattern, developed and used with considerable success by UK-based general practitioner and surgeon Dr. Naveed Akhtar, gains its effectiveness by eliciting both a sense of playfulness and a commitment to change—both important contributors to putting movement back into a life that appears ‘stuck’.

‘It seems that some people who are depressed, struggle to make decisions, refuse to socialize, and lack motivation. So I present them with the “Yes Game” as follows,’ he says.

‘When I’m confident that I have enough rapport with them, I suggest they try this exercise to see for themselves how their mood can change with just a simple shift in mindset.

‘All they have to do, I tell them, is to say, “Yes” to every invitation or suggestion they receive during one week. Of course, it has to be appropriate…nothing dangerous or upsetting. All suggestions must be within reason. But, apart from that, they must agree not to turn down anything that is asked of them.

‘This means, any time anyone invites them out, to go to a movie, or dinner, or try a new hobby, whatever it may be—they have to say, “Yes”… and follow through on the commitment.’

Our own experience with this pattern is: the better your engagement with the patient, the better the outcome. Plus, it’s always worth pointing out to those who agree that they’ve already said their first, ‘Yes’.

Case history: The husband of a 60-year-old lady died rather suddenly and unexpectedly. For several months, she became very depressed and reclusive. Her job as a primary school teacher started to become affected. She was prescribed anti-depressants and had several counseling sessions but there seemed to be very little improvement in her mood.

She would visit the GP often, and during one consultation mentioned that several of her friends and family members had asked her to go out with them, but she always refused. She felt guilty for going out when her husband was not around to go out with her.

She was then asked to play the ‘Yes Game’ as described above. Within a few short weeks, she was going out with friends and work colleagues, had started dancing again and met a nice gentleman with whom she had struck a close friendship. By committing to a set instruction she no longer felt guilty, having ‘permission’ to enjoy herself, and was able to move forward with her life.

Notes

273. Ogden P, Minton K, Pain C (2006) Trauma and the Body. New York: Norton.

274. Epel E, Blackburn E, Lin J, et al (2004) Accelerated telomere shortening in response to exposure to life stress. PNAS 101: 17312-17315.

275. Jacobs TL et al (2011) Intensive meditation training, immune cell telomerase activity, and psychological mediators. Psychoneuroendocrinology 36(5): 664-681.

276. For an easily accessible and impressive account of recent developments in research into neuroplasticity, we recommend Norman Doidge’s book, The Brain that Changes Itself (New York: Viking Penguin, 2007).

277. Feltz DL, Landers DM (1983) The effects of mental practice on motor skill learning and performance: a meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Psychology 5: 25-57.

278. Yue Guang, Cole K (1992) Strength increases from the motor program: comparison of training with maximal voluntary and imagined muscle contractions. Journal of Neurophysiology 67(5): 1114-23.

279. Moseley GL (2004) Graded motor imagery is effective for long-standing complex regional pain syndrome: a randomized, controlled trial. Pain 108: 192-8.

280. Pascual-Leone A, Hamilton R (2001) The metamodal organization of the brain. Progress in Brain Research 134: 427-45.

281. Henningsen P, Zipfel S, Herzog W (2007) Management of functional somatic syndromes. Lancet 369: 946-55.

282. Scaer RC (2001) The Body Bears the Burden: Trauma, Dissociation and Disease. New York: Haworth Medical Press.

283. Bakal D (1999) Minding the Body: Clinical Uses of Somatic Awareness. New York: Guilford Press.

284. Koriat A, Goldsmith M, Pansky A (2000) Toward a psychology of memory accuracy. Annual Review of Psychology 51: 481-537.