Chapter 2

The Fractional Exponential Function via the Fundamental Fractional Differential Equation

2.1 The Fundamental Fractional Differential Equation

This chapter develops the F-function as the solution of the fundamental fractional differential equation equation (2.1). A similar function was first used by Robotnov [112, 113]. The F-function was given in a footnote by Oldham and Spanier [104], p. 122, and later independently found by Hartley and Lorenzo [45, 48] as the solution to equation (2.1). This function is the foundation to the development of the fractional trigonometries. Following our study of the F-function, we introduce the R-function, which generalizes the F-function by including its fractional derivatives and integrals. The derivations of this chapter are abstracted from Hartley and Lorenzo, NASA [45]:

The problem to be addressed is the solution of the uninitialized fractional-order differential equation

where  is the initialized qth-order derivative and

is the initialized qth-order derivative and  represents the uninitialized qth-order derivative. Here, it is assumed for simplicity that the problem starts at t = 0, which sets c = 0. It is also assumed that all initial conditions, or initialization functions, are zero; thus,

represents the uninitialized qth-order derivative. Here, it is assumed for simplicity that the problem starts at t = 0, which sets c = 0. It is also assumed that all initial conditions, or initialization functions, are zero; thus,  . We are primarily concerned with the forced response. Rewriting equation (2.1) with these assumptions gives

. We are primarily concerned with the forced response. Rewriting equation (2.1) with these assumptions gives

We use Laplace transform techniques to obtain the solution of this differential equation. In order to do so for this problem, the Laplace transform of the fractional differential is required. Using equation (1.11) and ignoring initialization terms, equation (2.2) can be Laplace transformed as

This equation is rearranged to obtain the transfer function

This transfer function of the fundamental linear fractional-order differential equation contains the fundamental “fractional” pole (discussed later) and is a basis element for fractional differential equations of higher order. Specifically, transfer functions can be inverse transformed to obtain the impulse response of a differential equation. The impulse response can then be used with the convolution approach to obtain the solution of fractional differential equations with arbitrary forcing functions. In general, if U(s) is given, the product G(s)U(s) can be expanded using partial fractions, and the forced response obtained by inverse transforming each term separately. To accomplish these tasks, it is necessary to obtain the inverse transform of equation (2.4), which is the impulse response of the fundamental fractional-order differential equation.

To obtain the solution for arbitrary q, it is necessary to derive the generalized fundamental impulse response for the fractional-order differential equation equation (2.4), as this is not available in the standard tables of transforms, such as Oberhettinger and Badii [103] or Erdelyi et al. [34]. This is derived in the following section.

2.2 The Generalized Impulse Response Function

Continuing from Ref. [45]:

To obtain the generalized impulse response, we expand the right-hand side of equation (2.4) in descending powers of s, and then inverse transform the series term-by-term. It is assumed that

. As the constant b in equation (2.4) is a constant multiplier, it can be assumed, with no loss of generality, to be unity. Then, expanding the right-hand side of equation (2.4) about

using long division gives

This power series, in

, can now be inverse transformed term-by-term using the transform pair

for k > 0. The result is

The right-hand side can now be collected into a summation and used as the definition of the generalized impulse response function

This function is the generalization of the common exponential function that is needed for the fractional calculus. Furthermore, the important Laplace transform identity

has been established. When u(t) in equation (2.2) is a unit impulse,  is seen to be the forced response of the fundamental fractional differential equation.

is seen to be the forced response of the fundamental fractional differential equation.

This section has established the F-function as the impulse response of the fundamental linear fractional-order differential equation. The F-function generalizes the usual exponential function and is the fractional eigenfunction. The solution of equation (2.2), with b = 1, the F-function, is shown for various values of q in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 The  -function versus time as

-function versus time as  varies from 0.25 to 2.0 in 0.25 increments.

varies from 0.25 to 2.0 in 0.25 increments.

We note that  is a generalization of the exponential function, since for

is a generalization of the exponential function, since for  ,

,

This generalization,  , is the basis for the solution of linear fractional-order differential equations composed of combinations of fractional poles of the type of equation (2.8).

, is the basis for the solution of linear fractional-order differential equations composed of combinations of fractional poles of the type of equation (2.8).

2.3 Relationship of the F-function to the Mittag-Leffler Function

The F-function is closely related to the Mittag-Leffler function,  [96–98], which, at this time is commonly used in the fractional calculus. For this reason, we discuss the Mittag-Leffler function briefly; from Ref. [45], we have the following:

[96–98], which, at this time is commonly used in the fractional calculus. For this reason, we discuss the Mittag-Leffler function briefly; from Ref. [45], we have the following:

This function is defined as

(Erdelyi et al. [34, 35]). Letting  , this becomes

, this becomes

which is similar to, but not the same as equation (2.7). The Laplace transform of this equation (2.11) can also be obtained via term-by-term transformation, that is

or equivalently

Thus, the Laplace transform of the Mittag-Leffler function can be written as

More importantly, from equation (2.14), the E-function and the F-function are related as follows:

Functions similar to the F-function are mentioned by other authors as well. Oldham and Spanier [104], p. 122 mention it in passing in a footnote discussing eigenfunctions. Also, Robotnov [112, 113] studied a closely related function extensively with respect to hereditary integrals; he calls it the ϶-function. Also, other authors have used less direct methods to solve equation (2.2). Bagley and Calico [11] obtain a solution in terms of Mittag-Leffler functions. Miller and Ross's [95] solution is in terms of the fractional derivative of the exponential function. They use the function

whose Laplace transform is

Also, Glockle and Nonnenmacher [38] obtain a solution in terms of the more complicated Fox Functions.

2.4 Properties of the F-Function

In this section, the eigenfunction property of the F-function is derived. This essentially means that the  -derivative of the function

-derivative of the function  , returns the same function

, returns the same function  for

for  (see equation (2.21). Then, from Ref. [45]:

(see equation (2.21). Then, from Ref. [45]:

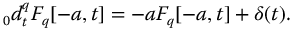

Taking the uninitialized qth-derivative

in the Laplace domain by multiplying by

gives

This equation can also be rewritten as

where the delta function is recognized as the unit impulse function. Now comparing equations (2.19) and (2.20), it can be seen that

This equation demonstrates the eigenfunction property of returning the same function upon

-order differentiation for t > 0. This is a generalization of the exponential function in integer-order calculus.

It is now easy to show that the F-function is the impulse response of the differential equation (2.2). Referring back to equation (2.2), and setting

and

, yields

For the F-function to be the impulse response, it must be the solution to equation (2.22), that is

. Substituting this into equation (2.22) gives

This equation has been obtained by direct substitution into the differential equation. Referring back to equation (2.21), however, shows that the qth-derivative of the F-function on the left-hand side is in fact equal to the right-hand side of equation (2.23). Thus, it is shown by direct substitution that the F-function is indeed the impulse response of the differential equation (2.22).

These sections have developed the F-function and the properties that are key to the development of the fractional trigonometry. The following section develops further important properties of the F-function and illustrates its application to the solution of fractional differential equations.

2.5 Behavior of the F-Function as the Parameter a Varies

This section studies the F-function with complex values for the parameter a. A linear system theory approach provides further understanding of the properties of the F-function, when its Laplace transform is considered as a transfer function of a physical system. From Ref. [45]:

Thus, we consider the Laplace transform of equation (2.22) as the transfer function of a related linear system

In general, to understand the dynamics of any particular system, we often consider the nature of the s-domain singularities. We define

in what follows. For a < 0, the particular function of equation (2.24) does not have any poles on the primary Riemann sheet of the s-plane (

), as it is impossible to force the denominator of the right-hand side of equation (2.24) to zero. Note, however, that it is possible to force the denominator to zero if secondary Riemann sheets are considered. For example, the denominator of the Laplace transform

does not go to zero anywhere on the primary sheet of the s-plane ( ). It does go to zero on the secondary sheet, however. With

). It does go to zero on the secondary sheet, however. With  , the denominator is indeed zero. Thus, this Laplace transform has a pole at

, the denominator is indeed zero. Thus, this Laplace transform has a pole at  , which is at

, which is at  on the second Riemann sheet. This is shown in Figure 2.2, where

on the second Riemann sheet. This is shown in Figure 2.2, where  is plotted as a function of Real(s) and Imaginary(s).

is plotted as a function of Real(s) and Imaginary(s).

As it is difficult to visualize multiple Riemann sheets, following LePage [65], it is useful to perform a conformal transformation into a new plane. Let

The transform in equation (2.24) then becomes

With this transformation, we study the w-plane poles. Once we understand the time-domain responses that correspond to the w-plane pole locations, we will be able to clearly understand the implications of this new complex plane. To accomplish this, it is necessary to map the s-plane, along with the time-domain function properties associated with each point, into the new complex w-plane. To simplify the discussion, we limit the order of the fractional operator to

. Let

Then, referring to equation (2.26)

Thus,

and

. With this equation, it is possible to map either lines of constant radius or lines of constant angle from the s-plane into the w-plane. Of particular interest is the image of the line of s-plane stability (the imaginary axis), that is,

. The image of this line in the w-plane is

which is the pair of lines at  . Thus, the right half of the s-plane maps into a wedge in the w-plane of angle less than

. Thus, the right half of the s-plane maps into a wedge in the w-plane of angle less than  degrees, that is, the right half s-plane maps into

degrees, that is, the right half s-plane maps into

For example, with

, the right half of the s-plane maps into the wedge bounded by

; see Figure 2.3.

It is also important to consider the mapping of the negative real s-plane axis,

. The image is

Thus, the entire primary sheet of the s-plane maps into a w-plane wedge of angle less than

degrees. For example, if

, then the negative real s-plane axis maps into the w-plane lines at

degrees; see Figure 2.3.

Continuing with the

example, and referring to Figure 2.3, it should now be clear that the right half of the w-plane corresponds to the primary sheet of the Laplace s-plane. The time responses we are familiar with from integer-order systems have poles that are in the right half of the w-plane. The left half of the w-plane, however, corresponds to the secondary Riemann sheet of the s-plane. A pole at

lies at

, on the secondary Riemann sheet of the s-plane. This point in the s-plane is really not in the right half s-plane, corresponding to instability, but rather is “underneath” the primary s-plane Riemann sheet. As the corresponding time responses must then be even more than overdamped, we call any time response whose pole is on a secondary Riemann sheet, “hyperdamped.” It should now be easy for the reader to extend this analysis to other values of q.

To summarize this, the shape of the F-function time response,

, depends upon both q and the parameter −a, which is the pole of equation (2.27). This is shown in Figure 2.4. For a fixed value of q, the angle

of the parameter −a, as measured from the positive real w-axis, determines the type of response to expect. For small angles,

, the time response will be unstable and oscillatory, corresponding to poles in the right half s-plane. For larger angles,

, the time response will be stable and oscillatory, corresponding to poles in the left half s-plane. For even larger angles,

, the time response will be hyperdamped, corresponding to poles on secondary Riemann sheets.

It is now possible to do fractional system analysis and design, for commensurate-order fractional systems, directly in the w-plane. To do this, it is necessary to first choose the greatest common fraction (q) of a particular system (clearly nonrationally related powers are an important problem although a close approximation of the irrational number will be sufficient for practical application). Once this is done, all powers of

are replaced by powers of w. Then the standard pole-zero analysis procedures can be done with the w-variable, being careful to recognize the different areas of the particular w-plane. This analysis includes root finding, partial fractions (note that complex conjugate w-plane poles still occur in pairs), root locus, compensation, and so on. We have now characterized the possible behaviors for fractional commensurate-order systems in a new complex w-plane; that is, given a set of w-plane poles, the corresponding time-domain functions are known both quantitatively and qualitatively. Although most of the discussion has actually been for

, it is reasonably applicable to larger values of q with the appropriate modifications for many-to-many mappings.

Figure 2.2 Both sheets of the Laplace transform of the F-function in the s-plane.

Source: Hartley and Lorenzo 1998 [45]. Public domain. Please see www.wiley.com/go/Lorenzo/Fractional_Trigonometry for a color version of this figure.

Figure 2.3 The w-plane for  , with

, with  .

.

Source: Hartley and Lorenzo 1998 [45]. Public domain.

Figure 2.4 Step responses corresponding to various pole locations in the w-plane, for  .

.

Source: Hartley and Lorenzo 1998 [45]. Public domain.

2.6 Example

In this example, we consider the impulse response of the inductor–supercapacitor pair shown in Figure 2.5. In the study of Hartley et al. [49], it was shown that a particular commercial supercapacitor is accurately modeled with the impedance transfer function  . The voltage across this device is chosen as the output voltage for this example. Then, in Figure 2.5, the voltage transfer function from the input terminals to the supercapacitor terminals is found to be

. The voltage across this device is chosen as the output voltage for this example. Then, in Figure 2.5, the voltage transfer function from the input terminals to the supercapacitor terminals is found to be

Figure 2.5 Supercapacitor circuit example.

For this example, we let  . Then,

. Then,

The poles and zeros of this transfer function are plotted on the w-plane in Figure 2.6, which also shows the 45° stability lines for q = 0.5. Clearly, there are two poles in the right half of the w-plane, but to the left of the stability boundary. These pole locations correspond to complex stable poles in the s-plane and imply a damped oscillatory impulse response. We obtain the impulse response of equation (2.34) using F-functions. First, it is necessary to define the new complex variable  . Then, assuming an impulse input, the output of the transfer function becomes

. Then, assuming an impulse input, the output of the transfer function becomes

Inverse transforming the partial fractions with  yields

yields

Figure 2.6 The w-plane stability diagram for supercapacitor.

This impulse response is plotted in Figure 2.7. Some damped oscillations are observed as expected from the pole-zero plot.

Figure 2.7 Supercapacitor impulse response.

This simple example is presented to demonstrate the use of the F-function to obtain the solution of a physical fractional-order system.

In this chapter, the fundamental linear fractional-order differential equation has been considered and its impulse response has been obtained as the F-function. This function most directly generalizes the exponential function for application to fractional differential equations. It is at the heart of our development of the fractional trigonometry. Also, several properties of this function have been presented and discussed. In particular, the Laplace transform properties of the F-function have been discussed using multiple Riemann sheets and a conformal mapping into a more readily useful complex w-plane.

It is felt that this generalization of the exponential function, the F-function, is the most easily understood and most readily implemented of the several other generalizations presented in the literature.