1

The BUILDUP

“An Overrehearsed Play”

The U.S. military started preparing for D-Day many years before it actually took place. A full national mobilization began even before Pearl Harbor, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940. After Germany declared war on the United States on December 11, 1941, the process of preparing for D-Day got under way full scale. Across the country, new military camps and training grounds appeared rapidly as the government attempted to expand the size of U.S. fighting forces with the greatest speed possible.

Soldiers from the U.S. Army’s 2nd Infantry Division mug for the camera during a training operation in the United Kingdom shortly before D-Day. Although they all wear standard infantry uniforms and equipment, some of these men also carry two pieces of specialized gear issued to troops involved in amphibious landing operations: the U.S. Navy inflatable invasion lifebelt and the M7 Assault Gas Mask Bag (worn over the chest). The soldier in the center front has his GI mess kit tucked under his left armpit, and the man to his right is using an M1936 canvas Musette Bag as a pillow.

The buildup of U.S. military forces in the United Kingdom began two years before the Normandy invasion. Here, a local police sergeant provides directions to 1st Sgt. Elco Bolton near Radford, England, on June 17, 1942. A native of Muscogee County, Georgia, Bolton enlisted in the army on January 17, 1939, in response to a recruiting drive for the Territory of Hawaii. Three years later, he was a senior NCO in a quartermaster trucking company near Birmingham in the West Midlands. First Sergeant Bolton is armed with the formidable M1928A1 Thompson Submachine Gun.

U.S. Army soldiers receive familiarization training on the use of the M7 Grenade Launcher in England shortly before the invasion. Introduced in February 1943, the M7 made it possible to launch various types of grenades with the M1 Garand rifle using the M3 .30-caliber Rifle Grenade Cartridge (a blank cartridge specifically made to propel rifle grenades from rifle-grenade launchers). In this photograph, the soldier kneeling in the center is about to fire off a Mk II fragmentation hand grenade mounted on his M1 rifle with an M1 Grenade Projection Adaptor. The soldier standing to his left has just pulled the pin on the hand grenade, the final step before firing.

Two U.S. Army soldiers from A Company, 121st Engineer Combat Battalion, 29th Infantry Division participate in a training exercise in England before the invasion. They are assembling sections of the infamous Bangalore torpedo, a demolitions weapon that was particularly effective at blowing gaps in barbed-wire entanglements. National Archives and Records Administration/US Army Signal Corps 111-SC-184811

The U.S. Army’s airborne units exemplify the swift expansion of U.S. fighting forces after hostilities began. Most of the paratroopers who jumped into Normandy on D-Day had received their basic training in the immediate aftermath of Pearl Harbor. Thus, the critical time period associated with America’s entry into the war and the masses of volunteers in late 1941 and early 1942 is also a period importantly associated with June 6, 1944. But, in addition to the preparations connected to training troops to expand the size of the military, American industry was building toward D-Day as well. Chrysler, Ford, Boeing, and other giants of industry produced the large-scale weapons—the tanks, trucks, and bombers—that Allied forces would eventually use in combat in northern France. U.S. businesses also produced small weapons at a breakneck pace. Although the Springfield Armory and Winchester were producing the semiautomatic M1 Garand service rifle as quickly as they could, there still were not enough to go around. The result was the distribution of a large number of M1903 bolt-action rifles to the troops who would ultimately come ashore on D-Day. Before the rifles, tanks, and troops could reach the beach, however, they had to reach Europe, and to do so, they needed ships. Kaiser Shipyards on the West Coast, Brown Shipbuilding in Texas, Alabama Drydock and Shipping in Mobile, and Bath Iron Works in Maine all built the fleet that would provide invaluable service during the invasion. In the New Orleans area, Higgins Industries produced one of the mission-critical tools for the eventual cross-channel invasion: landing craft. Although small in stature, these vessels were of the greatest import because they would make it possible to transfer personnel and equipment from big ships in deep water across the open beaches.

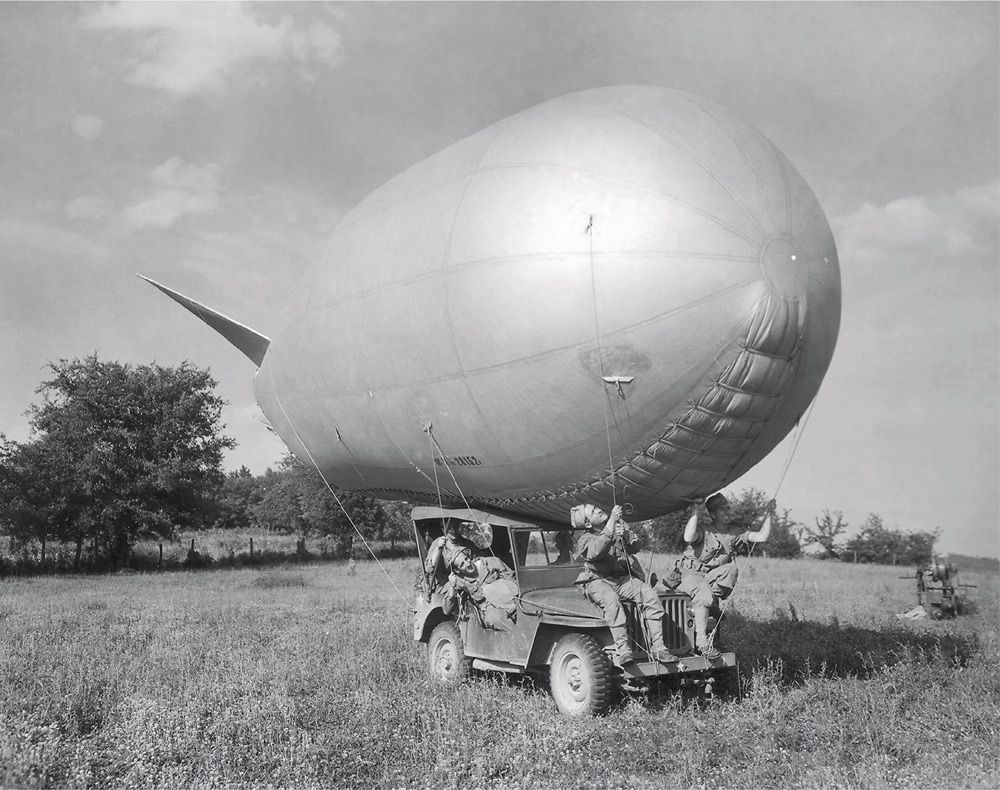

U.S. Army soldiers use a Jeep to move a Very Low Altitude (VLA) antiaircraft balloon during a training exercise in southern England before D-Day. The VLA balloon could be moored to the ground or to a ship by a heavy mooring cable, but its lift was not particularly strong, so it could be moved using the method depicted here. The VLA balloon provided a simple yet effective means of preventing enemy aircraft from conducting strafing or dive-bombing attacks. National Archives and Records Administration/US Army Signal Corps 111-SC-179839

A field full of U.S. Army M1 40mm Automatic Antiaircraft Guns and M1A1 90mm Antiaircraft Guns awaits the cross-channel attack that will bring them into contact with the enemy. Sights like this were common across England during the buildup toward D-Day. Each weapon is covered with a canvas tarp to prevent exposure to the elements. National Archives and Records Administration/US Army Signal Corps 111-SC-189322

A lone soldier looks out over a field full of M3 37mm Antitank Guns and M1A1 90mm Antiaircraft Guns during the buildup of military equipment in England prior to the Normandy landings. National Archives and Records Administration/US Army Signal Corps 111-SC-189324

Ford GPA amphibious utility vehicles and Dodge WC-51 Weapons Carriers sit in a field in England waiting for the impending invasion that will take them to France. By this stage of the war, the U.S. Army was a thoroughly mechanized fighting force that would soon become a critical part of a sweeping war of maneuver in northwestern Europe. National Archives and Records Administration/US Army Signal Corps 111-SC-189323

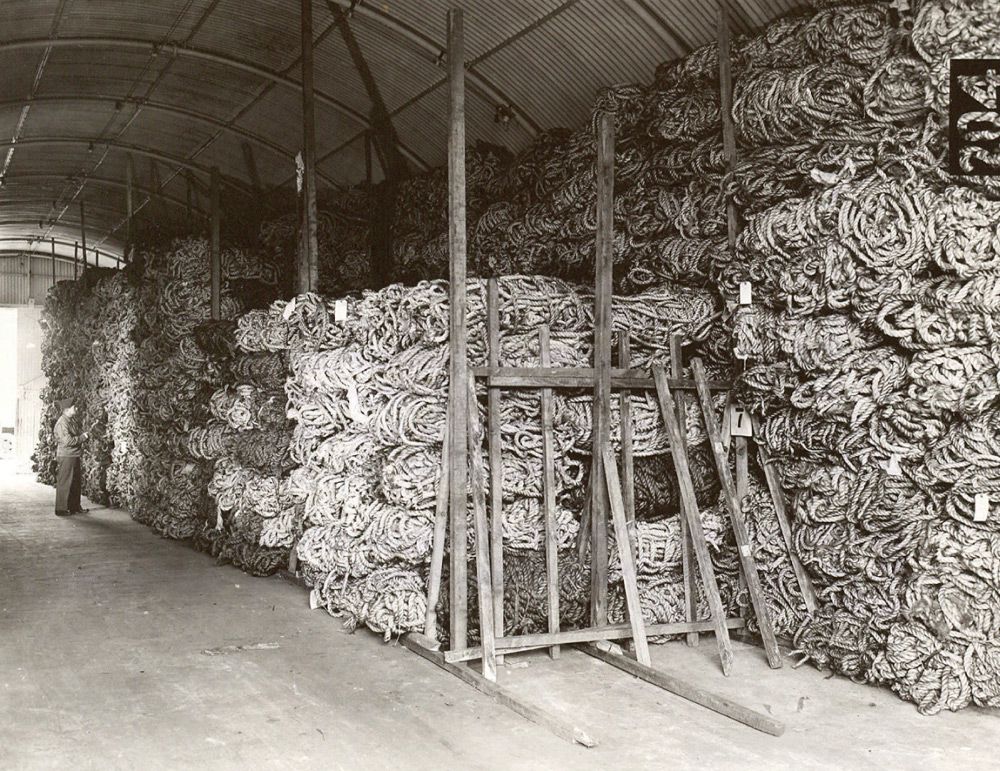

A U.S. Army corporal takes inventory of a warehouse storing rope bundles. Although not usually considered an important part of the U.S. Army’s military might, rope would become a valuable commodity during the campaign that followed the D-Day landings. National Archives and Records Administration/US Army Signal Corps 111-SC-189805

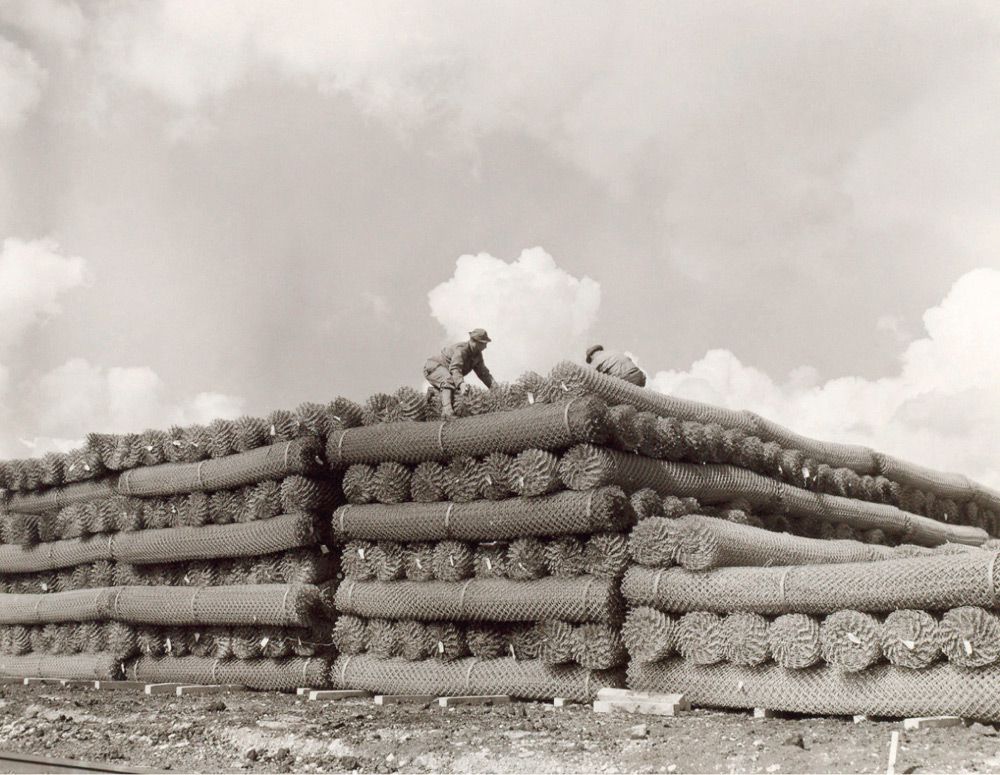

U.S. Army soldiers stack bundles of Square Mesh Track (SMT) that will be used as a surfacing material in the construction of advanced landing grounds in France after the invasion. National Archives and Records Administration/US Army Signal Corps 111-SC-189363

African-American U.S. Army soldiers stack bundled sections of Perforated Steel Planking (PSP) at a supply depot in England shortly before D-Day. Sometimes referred to as “Marsden” or “Marston” matting, PSP was a standardized, perforated-steel matting material developed to facilitate the rapid construction of temporary runways and landing strips. Sections of this matting could be easily interlocked to provide a stable, all-weather surface that could facilitate the swift establishment of advanced airfields. PSP was a critically important asset supporting the projection of airpower over northern France. National Archives and Records Administration/US Army Signal Corps 111-SC-189325

This view of the engineer depot at Thatcham, Berkshire, shows some of the different types of construction vehicles being amassed in England prior to the invasion. Here, Allis-Chalmers HD10W tractors, Caterpillar D4 tractors, and Caterpillar D7 bulldozers can be seen parked together in anticipation of the journey toward Germany. National Archives and Records Administration/US Army Signal Corps 111-SC-189366

Two soldiers inspect the inflation cylinders on U.S. Army rubber rafts in England before D-Day. National Archives and Records Administration/US Army Signal Corps 111-SC-189806

For all the contributions of the factories and training areas back in the United States, preparations for D-Day played out in the United Kingdom in earnest. There the war created a clash of cultures as service personnel from several nations descended on the islands during the pre-invasion buildup. From Northern Ireland to Wales, Scotland, and England, the United Kingdom became a maneuver area for the air, ground, and naval forces that would one day be called on to liberate Europe. The preparations for D-Day were so thorough and frequently repeated that newspaper correspondent Alan Moorehead described them as “an overrehearsed play,” indicating an anxious impatience to get the show on the road. For the British, who had experienced the war in a completely different way than the Americans, the reality was stark: since 1940, they had experienced bombings, food rationing, and fear of invasion. They had endured the loss of family and friends in addition to the absence of thousands of British soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines who were overseas serving in Asia, North Africa, or the Mediterranean. For them, total war was not a distant abstraction they read about in headlines—it reached across the English Channel from the continent. Then, the Americans began arriving in 1942. U.S. troops by the tens of thousands had come to prepare for the assault on fortress Europe. In the United Kingdom, cities swarmed with young American men who had not yet experienced war in the way the British had. But that was about to change.

Perhaps the best remembered aspect of the Operation Fortitude deception effort that preceded D-Day was the inflatable Sherman tank. By populating phony marshaling areas with these decoys, the Allies could trick German photoreconnaissance interpreters into believing they were assembling armored forces in areas of England where they were not actually doing so. The overall objective of this subterfuge was to “induce the enemy to make faulty strategic dispositions of forces.” (This quote comes from the Plan BODYGUARD Deception Policy operational order dated December 25, 1943. It is available through numerous sources, including a complete reprint in Fortitude: The D-Day Deception Campaign by Roger Hesket.)

Meanwhile, in France

During the months that preceded June 6, the French experienced the full landscape of hardships associated with being an occupied country. On an almost daily basis, Allied aircraft subjected northern France to heavy bombardment. In an effort known as the “Transportation Plan,” these bombings targeted the enemy’s means of movement. Bridges, railroad marshaling yards, rolling stock, and highways were rapidly reduced to rubble in an attempt to degrade Germany’s ability to move equipment and personnel in response to an invasion. While targets like the battery at Pointe du Hoc and the Fortress of Mimoyecques near Landrethun-le-Nord in the Pas-de-Calais region were easily hit from high altitude, others were well concealed and, therefore, less obvious. This resulted in collateral damage among French civilians, who, by this time, had endured the often harsh realities of life under German occupation for years. Throughout this time period, rationing, curfews, deportations, and even reprisals were part of everyday life. There were even employment offices that existed only to recruit young French people to relocate to Germany to do jobs that had been left vacant by the Third Reich’s war effort. But, in the background of all of this activity, the French Resistance was becoming an increasingly active and dangerous network of saboteurs and spies that challenged the German occupation.

Landing craft were among the most important weapons needed to carry out the Normandy invasion, and American industry answered this requirement by mass-producing a variety of different models. This photograph, taken at the beginning of 1944, shows the Bayou St. John testing area for New Orleans–based Higgins Industries. Here, Higgins boats were tested before being delivered to the military. Among the models seen here are the Landing Craft, Support (LCS) (small); the Landing Craft, Personnel (LCP) (large); the Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel (LCVP); and the seventy-eight-foot Higgins PT Boat. On the left, three LCVPs have been loaded onto railroad flat cars for over-land transportation.

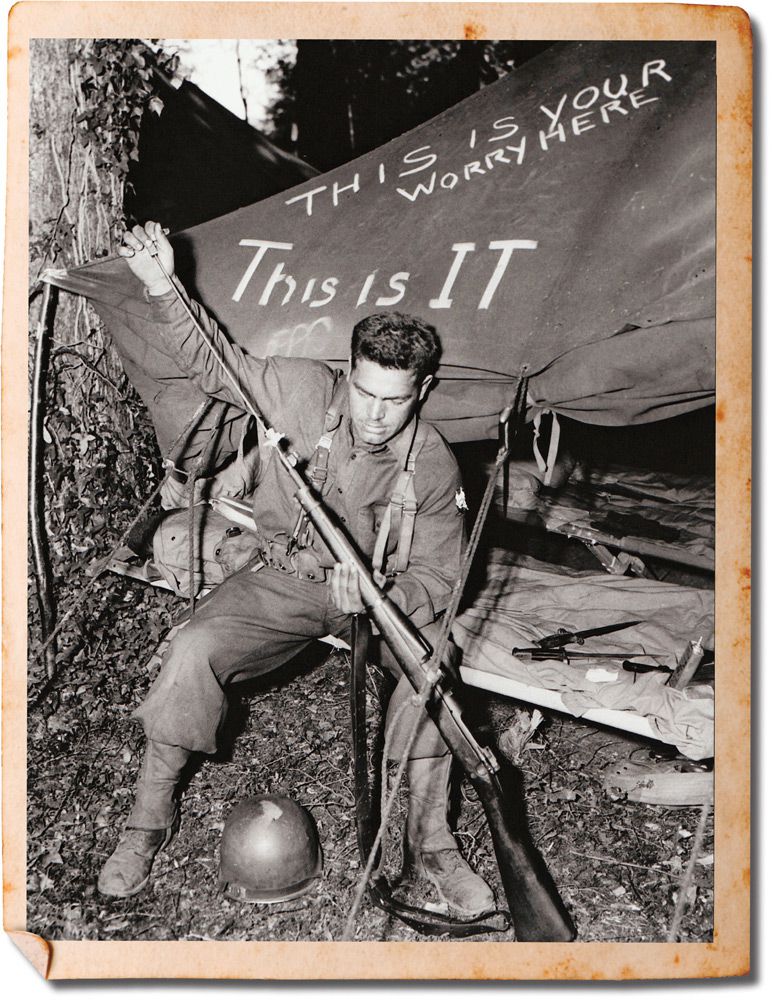

“This is your worry here—this is it.” A U.S. Army soldier cleans his M1903 bolt-action rifle in a camp in England shortly before the Normandy invasion. Although the U.S. Army had adopted the semiautomatic M1 Garand rifle in 1937, a large number of M1903s were still being issued in 1944.

U.S. Army soldiers billeted on the grounds of the English castle seen here in the background drive through the estate’s gate on the way to an invasion training session on April 18, 1944. In addition to having become a sprawling supply depot, by 1944, England had also become one vast maneuver and training area. Note that a censor has scratched out unit information beneath the right headlight of the M8 Greyhound armored car that is just passing through the gate.

Waiting and the Weather

D-Day was not scheduled to be Tuesday, June 6, 1944. It was scheduled to begin on Monday, June 5, but during the weekend a front moved in over the English Channel, bringing heavy rain, strong winds, and high seas. The operation was postponed by twenty-four hours because of the weather. General Dwight D. Eisenhower made the decision to postpone during a meeting at his headquarters at Southwick House, which was the advance command post of the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force (SCHAEF) near Portsmouth in Hampshire County. At the time of the postponement on Sunday, June 4, Eisenhower instructed the staff to reconvene the following day to determine if meteorological conditions had improved. When the team assembled again on Monday, June 5, Group Captain J. M. Stagg (SCHAEF chief meteorologist) reported a probable break in the weather. Eisenhower then polled the staff to consider their opinions about whether or not to go, and there was a 50/50 split. Despite this, Eisenhower believed it was time for “ramming our feet into the stirrups,” so he gave the order to begin the operation by saying, simply, “OK, let’s go.”

U.S. Army troops pass British civilians as they march toward their embarkation port shortly before D-Day. In this interesting photograph, the men can be seen wearing M1937 Olive-Drab Wool Field Trousers, M1937 Olive-Drab Flannel Shirts, Russet Service Shoes, and Leggings. One man is carrying an M1 2.36-inch rocket launcher (or “bazooka”) while the rest all seem to be carrying the M1 Garand rifle. One of the soldiers is in mid-salute, while the driver of the sedan on the left is displaying the “V” for victory sign. Behind that is a Ford GP (or “Jeep”) being driven by an African-American soldier. Farther back in the road column a GMC CCKW 2.5-ton Cargo Truck follows a Harley-Davidson WLA Motorcycle.

A column of trucks from B and C Batteries, 32nd Field Artillery Battalion pauses on the side of a road in southern England as it moves toward the port of embarkation in June 1944. The GMC CCKW 2.5-ton Cargo Truck in the center of the photograph is towing an M2A1 105mm Howitzer marked Djebel Berda and Mt. Etna, indicating that it saw combat in Sicily the previous summer. The 32nd Field Artillery provided artillery fire support for the 1st Infantry Division during the battle for France.

General Dwight David “Ike” Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force. Ike ultimately gave the order to begin Operation Neptune/Overlord by saying “OK, let’s go” at Southwick House near Portsmouth in Hampshire.

General Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force. His instructions for the upcoming cross-channel invasion, and the drive toward Germany itself, were outlined in a simple, thirty-word operational order: “You will enter the continent of Europe and, in conjunction with the other united nations, undertake operations aimed at the heart of Germany and the destruction of her armed forces.”

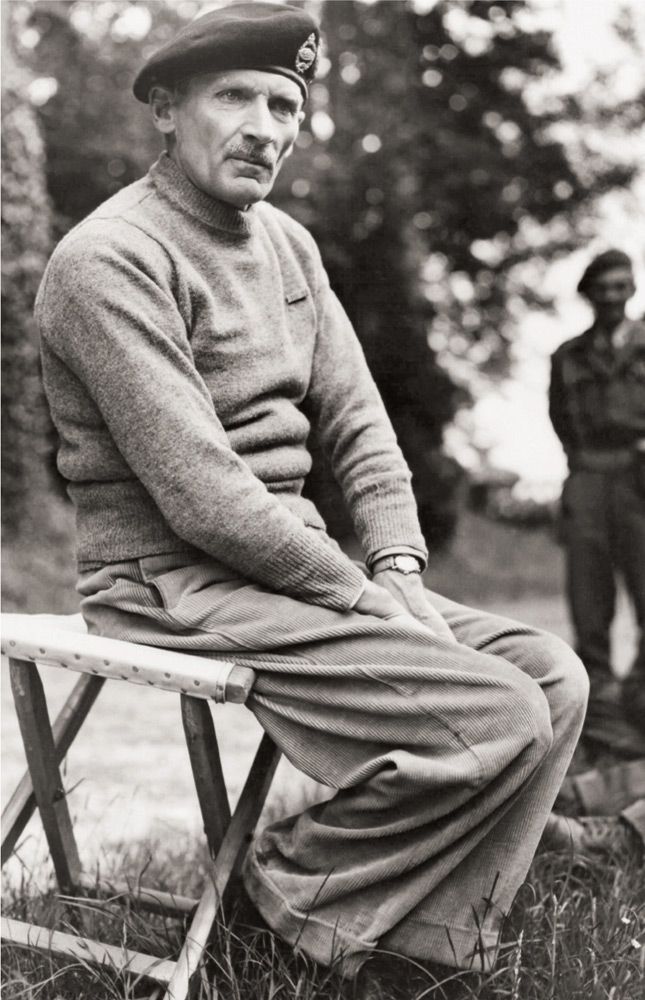

General Bernard Law Montgomery answers questions from war correspondents at his command post on the grounds of Château de Creully near the town of Creully during his first press conference after the Normandy landings. Although he would soon be promoted to the rank of Field Marshall, at the time this photograph was taken, he held the rank of General in command of the Allied 21st Army Group. National Archives and Records Administration/US Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190425

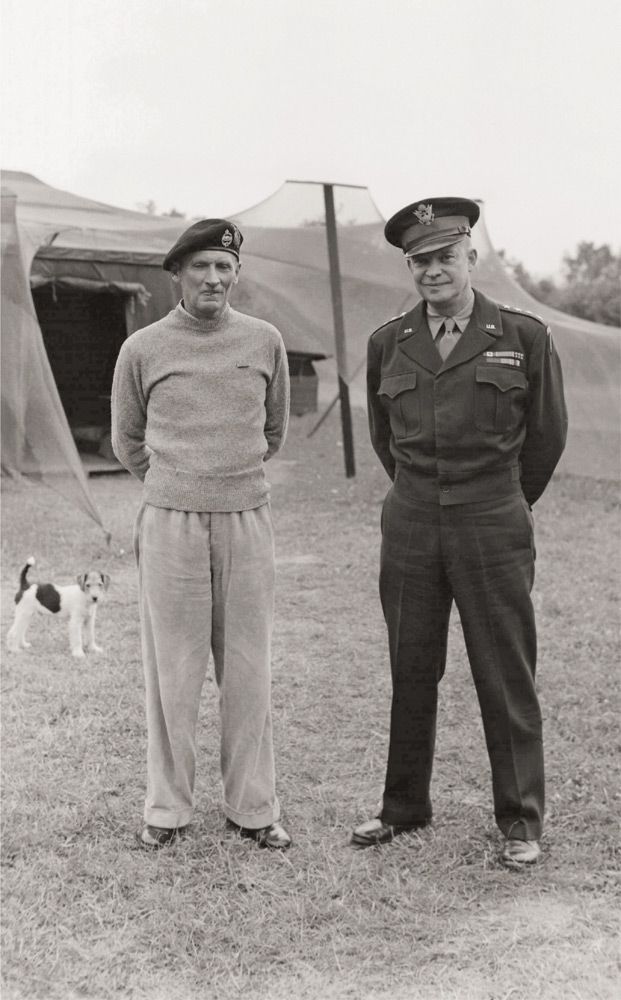

General Sir Montgomery, commander of the Allied 21st Army Group, and General Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, pose at General Montgomery’s field command post in Normandy on July 26, 1944. These two men exercised overall control of the ground battle in Normandy. In the background is one of General Montgomery’s many mascots: a wire fox terrier he named “Hitler.” National Archives and Records Administration/US Army Signal Corps 111-SC-192193

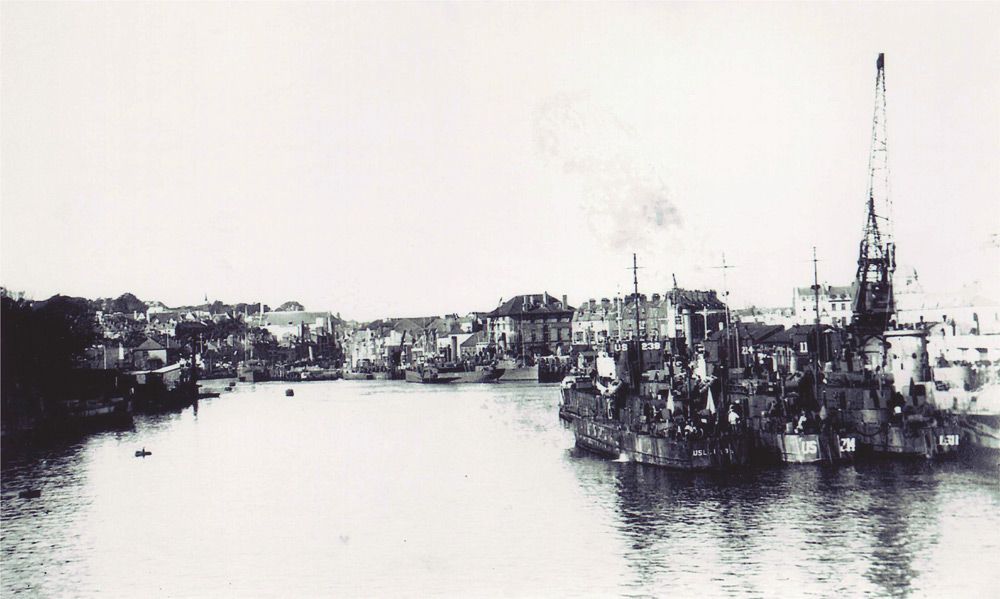

Landing Craft, Infantry (LCI)-238, LCI-214, and LCI-311 moored together along the waterfront in Weymouth, Dorset, shortly before the Normandy invasion. The buildings in the background at the center of the photograph line Custom House Quay between the Esplanade and Maiden Street.

An M4A3 Sherman medium tank of the 66th Tank Battalion, 2nd Armored Division backs aboard a U.S. Navy Landing Ship, Tank (LST) in England during the embarkation phase that necessarily preceded crossing the English Channel. Note the U.S. Navy officer perched on the upper hinge of the ship’s portside bow door. National Archives and Records Administration

A Jeep is lowered onto a Higgins Landing Craft, Mechanized (LCM)-3 from the Harris-class attack transport USS Joseph T. Dickman (APA-13).

A GMC CCKW 353 2.5-ton truck nicknamed “Lil’ Nellie” is loaded aboard LST-134 at Portland Harbour in Dorset during embarkation before D-Day. A deep-water fording kit has been installed on “Lil’ Nellie,” and she has a camouflage net lashed to her left front wheelwell. LST-134 carried elements of the divisional headquarters for the 1st Infantry Division to the Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944.

Loading LST-357 at Portland Harbour in Dorset during embarkation before D-Day. In the foreground, a Dodge WC-51 Winchless Weapons Carrier and a GMC DUKW 353 2.5-ton amphibian truck prepare to come aboard. The emblem above the throat leading to the ship’s tank deck depicts a stork (nicknamed “Palermo Pete”) and the motto “We Deliver.” By June 1944, LST-357 had already participated in the Operation Husky landings in Sicily (July 1943) and the Operation Avalanche landings at Salerno, Italy (September 1943). On D-Day, “Palermo Pete” landed elements of the U.S. Army V Corps on the Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach.

A Jeep from the Engineer Special Brigade’s medical unit drives aboard a Landing Craft, Tank (LCT) nicknamed “Channel Fever” at Castletown near Portland (south of Weymouth) in Dorset during embarkation for D-Day.

Jeeps and personnel from the 1st Infantry Division on board the LCT “Channel Fever” at Castletown near Portland (south of Weymouth) in Dorset. Among the soldiers and sailors seen here are two U.S. Navy ensigns (standing shoreside between two soldiers) as well as troops from the 5th Engineer Special Brigade and the 741st Tank Battalion.

Three U.S. Army combat engineers from either the Special Engineer Task Force or Beach Obstacle Demolition Party move to their embarkation assembly area in preparation for D-Day. Each soldier carries a section of Bangalore torpedo on his shoulder, reels of Primacord, and an M7 Assault Gas Mask Bag worn on his chest. The man in the center already has his M1 Garand rifle packed in a Pliofilm bag to protect it from sand during the landing. National Archives and Records Administration

In this photograph, taken on Thursday, June 1, 1944, U.S. Army Rangers march along the waterfront in Weymouth, Dorset, to meet the landing craft that will carry them to the transports anchored in the harbor. The Rangers remained aboard their ships during the coming days as a security precaution. Here, men can be seen carrying Bangalore torpedo sections, M7 Assault Gas Mask Bags, U.S. Navy invasion inflatable lifebelts, and assault/invasion vests in dark-green canvas (which were distributed ten days before the invasion).

Jeeps and personnel from the 1st Infantry Division on board the LCT “Channel Fever” at Castletown near Portland (south of Weymouth) in Dorset. Among the men seen here are a sailor and soldiers from the 5th Engineer Special Brigade and the 741st Tank Battalion.

This photograph shows the intersection where Custom House Quay and the Esplanade meet on the waterfront in Weymouth, Dorset. At the time this photo was taken during the first week of June 1944, the embarkation for Operation Neptune was well under way. In the background, LCI(L)-497; LCH-87 can be seen nested together alongside the quay. At the center are two trailers carrying bottles of compressed hydrogen used to inflate VLA antiaircraft barrage balloons like the three secured to the ground with nets and sandbags in the foreground. At center right can be seen an International Harvester 4x4 Truck, a closed-cab GMC 353, a U.S. Navy 6x6, three Dodge WCs, and a Diamond T Model 972 Dump Truck.

Soldiers from the medical section of either the 5th or the 6th Engineer Special Brigade board an LCT at Castletown near Portland (south of Weymouth) in Dorset during embarkation before D-Day.

At the intersection of Custom House Quay and the Esplanade on the waterfront in Weymouth, Dorset, U.S. Army Rangers have begun boarding five Royal Navy Landing Craft, Assault (LCAs) for the trip out to their transport anchored in the harbor during embarkation shortly before D-Day. In the background, LCI(L)-497, LCI(L)-84, and LCH-87 can be seen nested together alongside the quay.

Thursday, June 1, 1944: Two Higgins LCM-3s from the USS Samuel Chase (APA-26) have pulled up to the seawall at the intersection of Custom House Quay and the Esplanade on the waterfront in Weymouth, Dorset. In the background, U.S. Army Rangers are loading five Royal Navy LCAs, and LCI(L)-497, LCI(L)-84, and LCH-87 are nested together.

Thursday, June 1, 1944: At the intersection of Custom House Quay and the Esplanade on the waterfront in Weymouth, Dorset, U.S. Army Rangers have boarded five Royal Navy LCAs for the trip out to their transport anchored in the harbor during embarkation shortly before D-Day. In the background, LCI(L)-497, LCI(L)-84, and LCH-87 can be seen nested together alongside the quay.

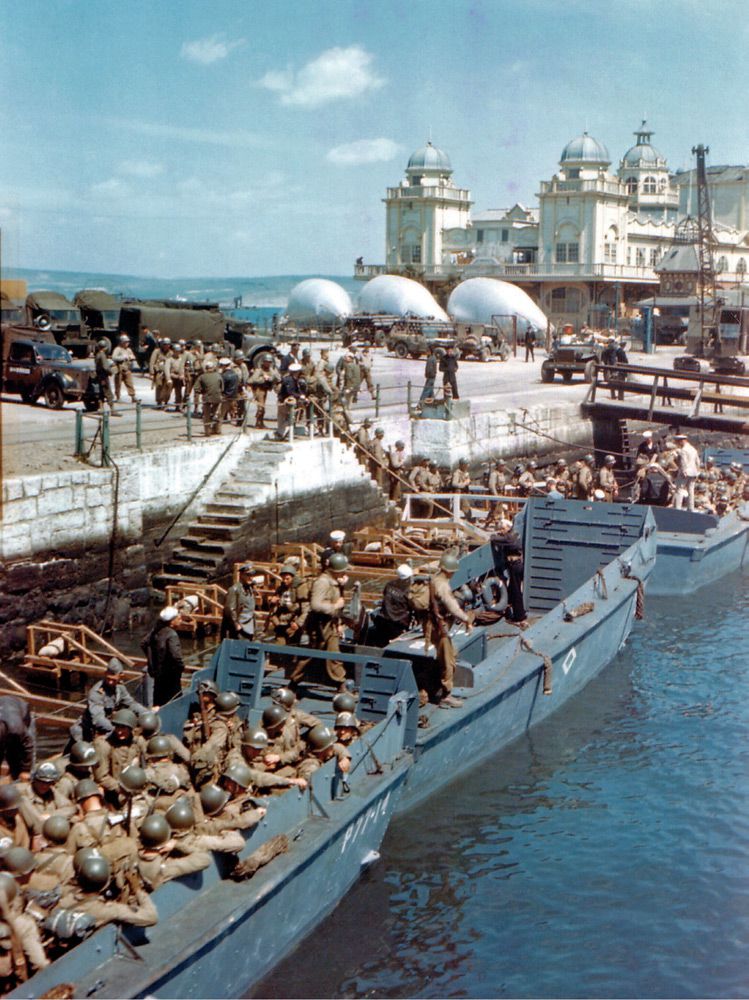

“Check Rosters Here”: U.S. Army Rangers make one last stop in this tent before boarding landing craft that will take them out to the transports that will ultimately carry them to Normandy. After checking in with officers of the Transportation Corps at the front of the tent, the men receive donuts and coffee from the Red Cross at the other end of the tent. The famous Weymouth Pavilion, requisitioned by the military during the war, is visible in the background.

Personnel of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade embarking on a Higgins LCVP from the USS Thurston (AP-77) using the portside ramp of LCI(L)-497 on the waterfront in Weymouth, Dorset while a VLA antiaircraft barrage balloon floats overhead.

U.S. Army soldiers loading a Higgins LCVP from the McCawley-class attack transport USS Barnett (APA-5) in Plymouth Harbor during a training exercise prior to D-Day. The LCVP next to it (marked PA13-25) belongs to the USS Joseph T. Dickman (APA-13), a Harris-class attack transport operated by the U.S. Coast Guard. Both the Barnett and the Dickman ultimately carried elements of the 4th Infantry Division to Utah Beach on D-Day. At the far left, a group of soldiers has already boarded an unidentified British LCA (probably from Empire Gauntlet).

U.S. Army Rangers from A Company, 5th Ranger Battalion boarding a British LCA in Weymouth Harbor, Dorset, during embarkation for D-Day on June 1, 1944.

U.S. Army Rangers from E Company, 5th Ranger Battalion aboard an LCA in Weymouth Harbor, Dorset, during embarkation for D-Day on June 1, 1944.

U.S. Army Rangers from E Company, 5th Ranger Battalion aboard an LCA in Weymouth Harbor, Dorset, during embarkation for D-Day on June 1, 1944. These men have been identified as T-5 Joseph J. Markowitz (with an M1A1 Rocket Launcher), Robert Presutti (partially obscured), and Corporal John B. Loschiavo (on the right with the M1 Garand rifle). At the far left, another Ranger can be seen holding a pack of Lucky Strike cigarettes, and his M1 rifle can be seen directly behind strapped to a section of Bangalore torpedo.

Higgins LCVPs loading troops at Portland Harbour during embarkation before D-Day. The landing craft in the foreground (PA30-13) is from the President Jackson–class attack transport USS Thomas Jefferson (APA-30). A Diamond T 969A 4-ton 6x6 wrecker can be seen in the background.

Two of LST-351’s six Higgins LCVPs pull alongside the ship in the middle of the River Tamar at Plymouth, Devon, during embarkation before D-Day. In the background is the distinctive and easily recognizable Royal Albert railway bridge linking Plymouth to Saltash in Cornwall.

A Higgins LCVP from the President Jackson–class attack transport USS Thomas Jefferson (APA-30) backs into Portland Harbour with a load of U.S. Army soldiers during embarkation before D-Day.

Three Higgins LCVPs pull alongside the Harris-class attack transport USS Joseph T. Dickman (APA-13) during the embarkation phase of Operation Neptune. National Archives and Records Administration/US Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190440

LCA-1377 carries Rangers from the U.S. Army’s 5th Ranger Battalion across Weymouth Harbor on Thursday, June 1, 1944, during embarkation for D-Day. This landing craft is boat number one from the HMS Prince Baudouin, a former Belgian cross-channel ferry impressed into Royal Navy service as Landing Ship, Infantry (LSI) (small)-488 after escaping from the German invasion in 1940. In the stern of the LCA, a Ranger medic can be seen with Geneva Convention markings on his M1 helmet and a similarly marked 60mm mortar shell case modified to carry medical supplies. The three Rangers in the bow area of the LCA are (from left to right): Lt. Stan Askin from the 1st Platoon of Company B, 5th Ranger Battalion; Capt. John C. Raaen, Jr., of Headquarters Company, 5th Ranger Battalion; and Maj. Richard P. Sullivan, Executive Officer of the 5th Ranger Battalion.

Men of the legendary 1st Infantry Division prepare to depart southern England for their voyage to France. This image provides details about the uniforms and equipment worn and carried by the soldiers who fought at Omaha Beach on D-Day. The men seen here are mostly wearing M1937 Olive Drab Wool Field Trousers, M1937 Olive Drab Flannel Shirts, and M1941 Field Jackets. Seven of the men seen here are wearing the winter combat jacket sometimes referred to as the “tanker jacket” because it was developed for issue to armored-vehicle crews. While almost everyone is wearing the M1 steel helmet, seven of the men are also wearing the issue M1 Helmet Eyeshields. Several M1 Rifles and M1 Carbines can be seen in the photo, and a few of them have already been encased in their clear Pliofilm protective bags, a necessity for an amphibious landing. The African-American soldier is wearing the M1942 Herringbone Twill (HBT) uniform and is not a member of the 1st Infantry Division but probably the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion (VLA). The soldier in the foreground with his pants legs rolled up is sitting on a green canvas assault vest.