5

POINTE du HOC

A FORCE OF 225 MEN from the U.S. Army’s 2nd Ranger Battalion received the special D-Day mission of landing at the base of Pointe du Hoc four miles west of Omaha Beach and scaling the cliffs there to conduct an assault against one of the most threatening German gun batteries in lower Normandy. Established in May 1942, Heeres-Küsten-Batterie Pointe du Hoc (WN75) was a position armed with six French-made 155mm breech-loading rifles. These guns had been captured in 1940 and subsequently placed in German Army service with the designation 15.5cm K 418(f). At Pointe du Hoc, they were mounted on concrete traversing tables that extended their maximum effective range, tightened their already impressive accuracy, and transformed them into formidable anti-ship weapons. The Ranger mission on D-Day, which was commanded by Lt. Col. James Earl Rudder, had the objective of preventing these guns from firing on the fleet.

One of the few photographs capturing Rangers in combat at Pointe du Hoc. Probably taken on June 7, the image shows an NCO (top right) firing an M1919A4 .30-caliber Machine Gun from a fighting position at the cliff’s edge. By his right foot are six cans of belted ammunition, providing an additional 1,500 rounds of .30-caliber cartridges for the weapon. On his M1936 Pistol Belt are an M1910 Entrenching Tool and an M17 Leather Field Glasses Case. The Ranger to his left wears the canvas assault vest with an M1910 Entrenching Tool attached to it. The Ranger at the far left has an M3 Trench Knife in an M8 Scabbard attached to his M1936 Cartridge Belt. A Ranger officer has his back to the camera at the bottom right. National Archives and Records Administration 111-SC-320894

A formation of Douglas A-20 Havoc light bombers flies northward to return to its base in England after just having bombed Heeres-Küsten-Batterie Pointe du Hoc (Army Coast Artillery Battery Pointe du Hoc). The repeated bombing of the site extensively damaged the concrete tables upon which the guns were mounted, ultimately resulting in their removal about five weeks before the invasion. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

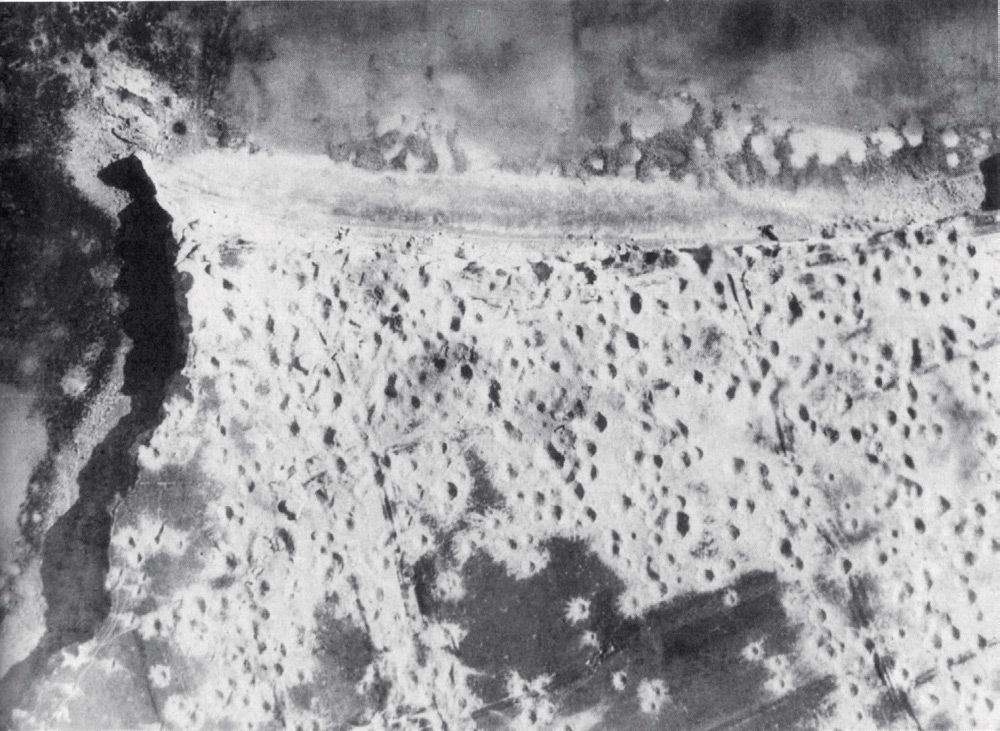

In this June 2010 aerial photograph of Pointe du Hoc, the heavy cratering caused by bombing and shelling during World War II can be seen clearly. At that time, a French engineering firm was working to stabilize the cliff face and the Type R636a battery command/fire control post bunker, which is why pieces of construction equipment are present on the site. This preservation project was done in cooperation with Texas A&M University’s Center for Heritage Conservation.

At 7:10 a.m., Rudder’s force landed from nine British Landing Craft, Assault (LCA), scaled the cliffs, and swiftly pushed the enemy back from the battery area. That is when the Rangers discovered that no guns were mounted at the point. Instead, timbers had been placed on each of the six concrete traversing tables to make it look as if the battery remained armed. The Rangers also found two casemates for heavy artillery at Pointe du Hoc (of Type H679), but they were still under construction, and their guns had not yet been mounted. In late April, the Germans had removed the guns from the point to a position almost a mile to the south in the hedgerows near La Montagne, but the Rangers did not know that. After they secured the WN75 battery position, they moved on to the next phase of their mission, which was to set up a roadblock on the Vierville/Grandcamp road (present-day D514). While doing this, the Rangers put out flank security and quickly stumbled across the guns concealed along a hedgerow-enclosed lane. First Sergeant Leonard “Bud” Lomell and Staff Sgt. Jack Kuhn then disabled the guns using Thermite grenades. Overnight on June 6 and 7, the Germans launched a series of powerful counterattacks from the direction of Grandcamp-Maisy, which pushed the Rangers back to the point. By the time vehicles from Omaha Beach linked up with Rudder’s force at Pointe du Hoc on June 7, the Rangers had suffered 135 casualties, most of which happened during the German counterattacks on the night of June 6.

A view of Pointe du Hoc taken from the west looking toward Îles Saint-Marcouf and the east coast of the Cotentin Peninsula. Utah Beach can be seen in the background just above the memorial on the battery command/fire control post.

Looking down on the point from the R636a fire control post bunker. The barbed wire that can be found around the site today was not there during the war.

A view from the gravel beach on the east side of Pointe du Hoc at low tide. Courtesy of Paul Woodadge

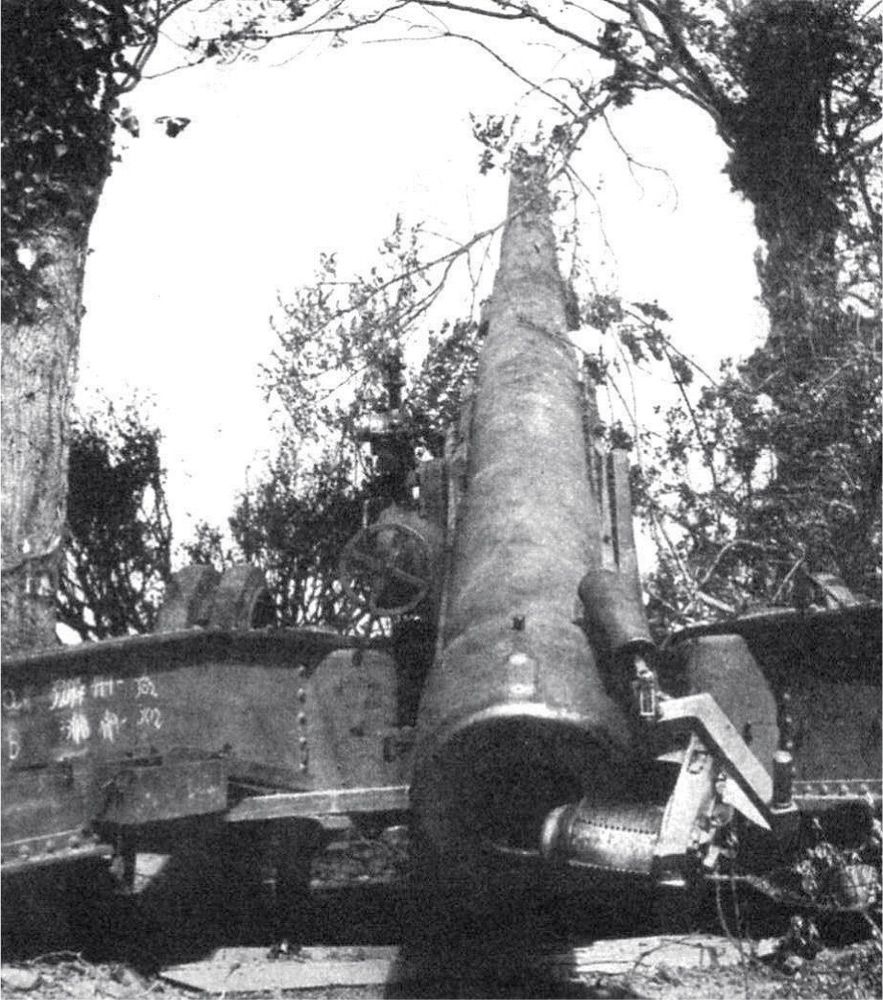

A Canon de 155mm modele 1917 in transit configuration but abandoned along the side of the road somewhere in France in 1940. Designed by Col. Louis Jean François Filloux, this weapon was referred to as grande puissance Filloux, or simply “GPF” for short. The Germans captured more than four hundred GPFs with the fall of France and, recognizing their outstanding quality, used them throughout the war under the designation 15.5cm K 418(f). Heeres-Küsten-Batterie Pointe du Hoc was armed with six GPFs.

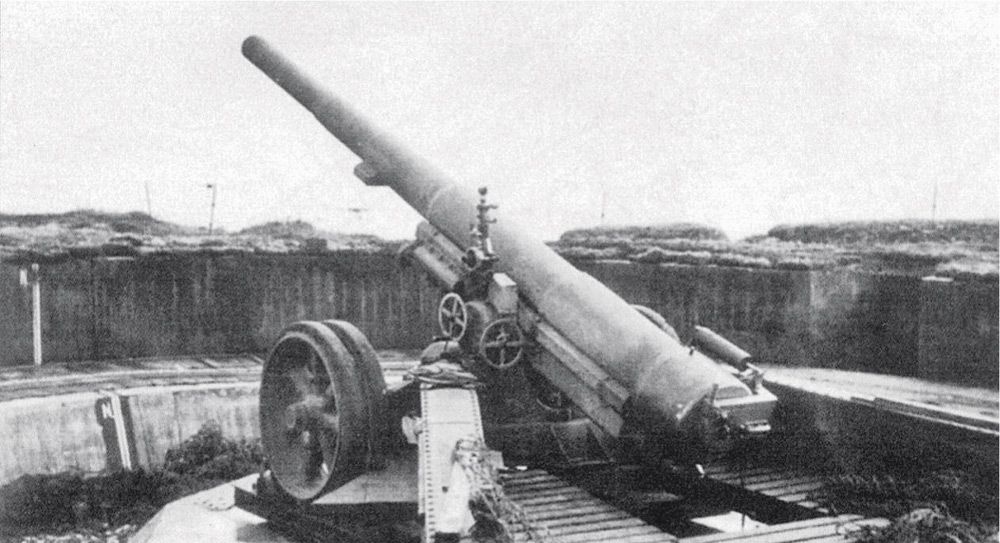

The six 15.5cm K 418(f)s that armed Heeres-Küsten-Batterie Pointe du Hoc were mounted on open concrete traversing tables that extended their range and enhanced their accuracy. Although the gun was a piece of field artillery, this mounting system transformed the GPF into a dangerous and powerful coast artillery weapon.

One of the six GPFs that armed Heeres-Küsten-Batterie Pointe du Hoc remains at the site today, although its carriage is gone.

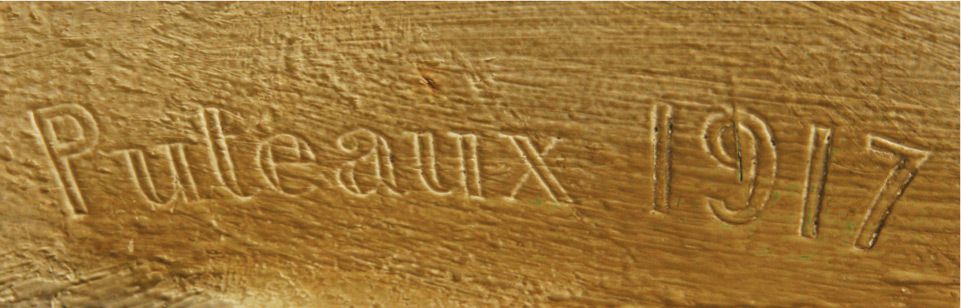

This marking above the breech on the GPF at Pointe du Hoc today indicates that Atelier de Puteaux in Paris manufactured it in 1917.

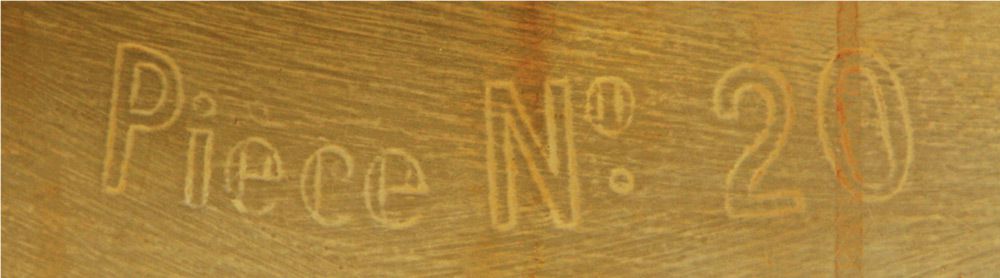

The lower breech marking on the GPF at Pointe du Hoc today reveals serial number 20.

A view of the eastern side of Pointe du Hoc from the beach showing the spoil pile created when 14-inch shells from the battleship USS Texas (BB-35) struck the face of the cliff. Official U.S. Navy photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives 80-G-45718

Because each of the six GPFs at Pointe du Hoc weighed over twenty-eight thousand pounds, each sat on a steel tray equipped with twelve rollers that rode on a concrete pintle block. This system evenly distributed the weapon’s weight and permitted 360 degrees of traverse. Although it is often overlooked, one of the steel trays remains on the site today.

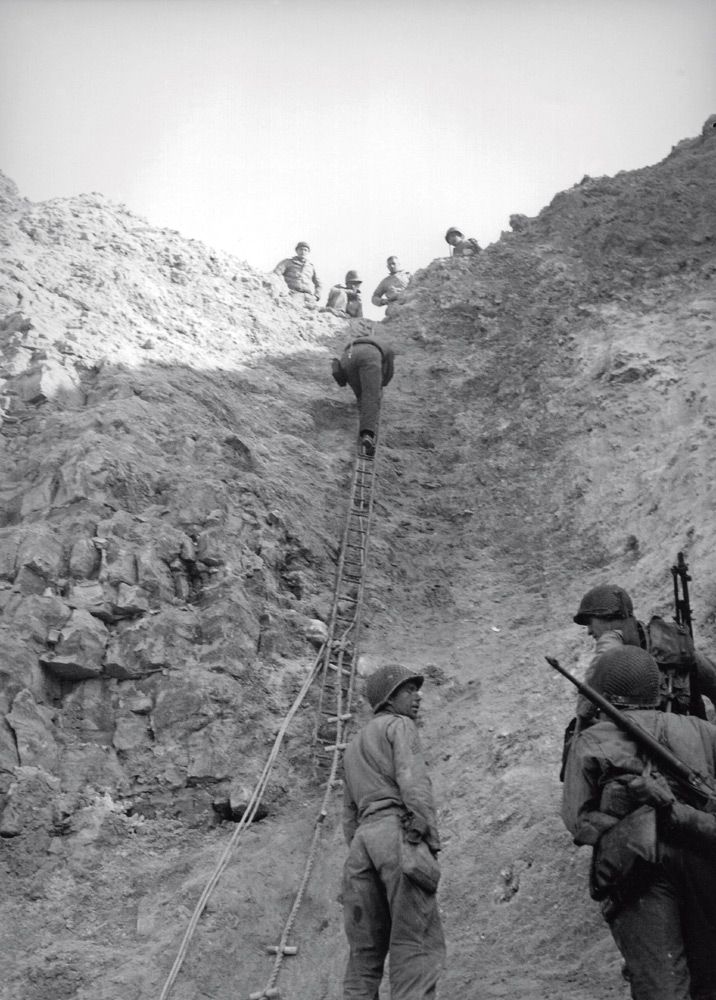

This may be the area where the Rangers who landed from LCA-888 managed to climb to the top using an extension ladder placed on a mound of debris knocked out of the cliff top. Although this photo was taken on D+2 (June 8, 1944) when the route was being used for supplies, it nevertheless illustrates the great difficulty associated with getting up the cliffs in the initial assault. A toggle rope and two plain ropes can be seen below the ladder. Official U.S. Navy photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives 80-G-45716

After the German soldiers of 2, Heeres-Küsten-Artillerie-Regiment, 1260 (the 2nd Battalion, Army Coast Artillery Regiment 1260) removed the GPFs from Pointe du Hoc during the night of April 25–26, 1944, they replaced them with timbers and wooden beams, hoping they would give the impression that the battery remained armed. Here, Sgt. Warden F. Lowell inspects one of the dummy pieces on June 8, 1944.

In this 1975 aerial photograph of the area around Saint-Pierre-du-Mont, Le Guay, La Montagne, and Pointe du Hoc, the six small yellow circles indicate the location of the six concrete traversing tables for the GPFs/15.5cm K 418(f)s, and the elongated yellow circle at the bottom left indicates the position of the guns on D-Day.

When five of the Pointe du Hoc GPFs were relocated five weeks before the invasion, they were moved up this dirt road at La Montagne.

This photograph was taken facing toward the west from the spot where five of the six GPFs from Pointe du Hoc were found on D-Day. In the distance just to the left of the buildings across the field, you can clearly see the Utah Beach landing area at La Madeleine 8.5 miles away.

One of the Pointe du Hoc GPFs is seen here in its hedgerow position near La Montagne. Without the stabilized concrete mount built for it at the point, the weapon would not have been quite as accurate, and its range would have been slightly reduced. Nevertheless, this GPF would have easily been capable of delivering accurate fire missions against targets landing on Utah Beach at La Madeleine.

In this photograph, taken shortly after D-Day, another of the Pointe du Hoc GPFs can be seen with its muzzle pointing over a cattle gate. Although the guns’ fire would have been slightly less dangerous from the position near La Montagne, the hedgerows concealed the GPFs from the Allied air attacks that were increasing in regularity during the weeks that preceded the invasion.

Two U.S. Army Rangers pose on the right split trail of the GPF seen in the photograph above. The wooden planks on the ground between the trails span a pit that has been excavated beneath the weapon’s breech to allow room for the gun tube to move through full recoil when firing at high elevation. Note that the weapon’s sight and breechblock are still in place.

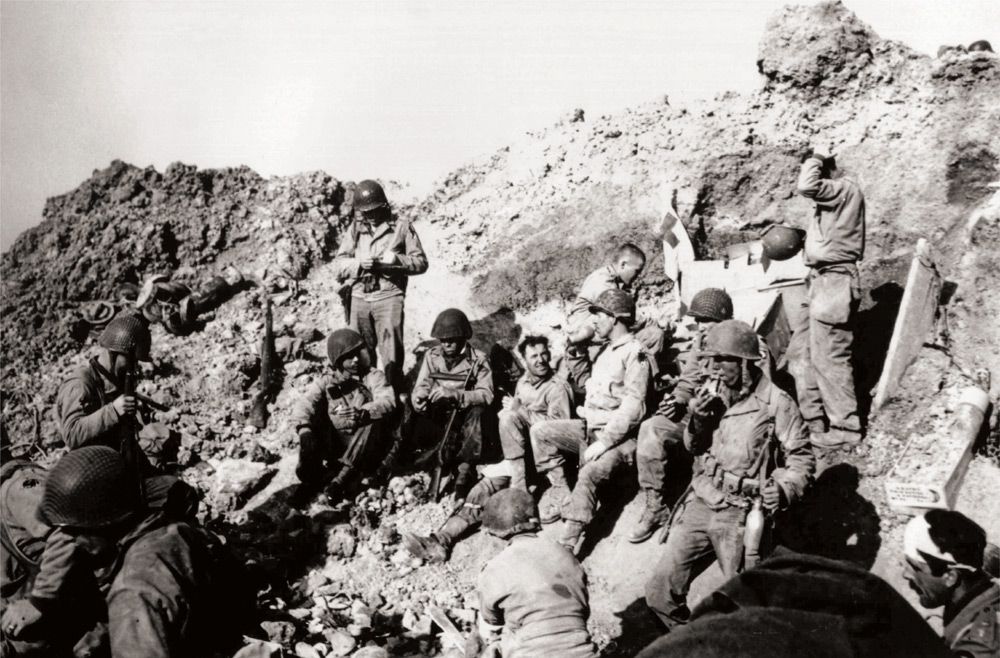

U.S. Army Rangers resting at Pointe du Hoc, which they assaulted in support of Omaha Beach landings on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Note that the Ranger on the right is apparently using his middle finger to push a cartridge into an M1 Carbine fifteen-round magazine and that a Ranger lozenge/diamond patch is sewn on the left shoulder of his M1941 Field Jacket. He is also still wearing an M7 Assault Gas Mask Bag. The Ranger in the center operates a radio while wearing a poison-gas-detection brassard over the left shoulder of his 1941 jacket. These paper armbands were impregnated with a reactive paint that would turn pink or red if exposed to poison gas. Official U.S. Navy photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives 80-G-45715

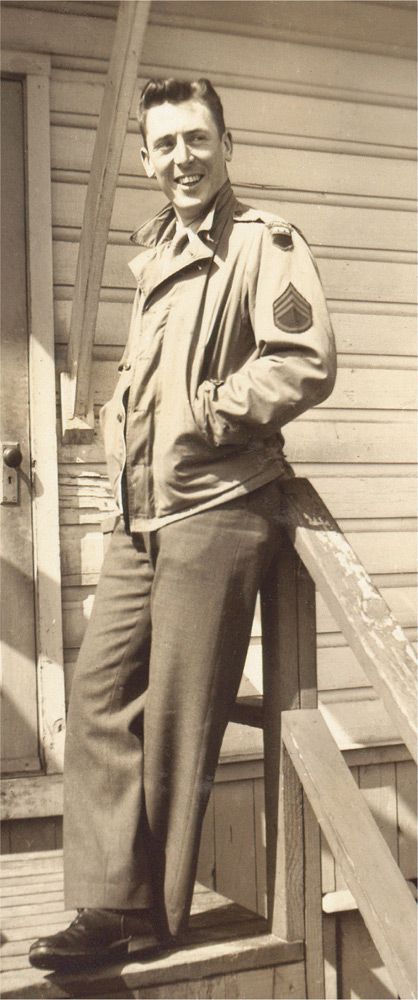

Leonard G. “Bud” Lomell, seen here when he was a Staff Sergeant in the 76th Infantry Division in early 1943, was serving as the First Sergeant of D Company, 2nd Ranger Battalion on June 6, 1944. Together with Staff Sgt. Jack Kuhn, First Sergeant Lomell was moving down one of the hedgerows south of the D514 coast road when he noticed a suspiciously large set of tracks in the mud. Those tracks led him to the spot near La Montagne where the five Pointe du Hoc GPFs were located.

This photograph of Lt. Col. James Earl Rudder’s command post at Pointe du Hoc’s eastern Type L409A antiaircraft bunker was taken in the afternoon on D-Day and reveals the many purposes a command post had to serve in combat: communications center, medical aid station, casualty collecting point, supply depot, etc. Perhaps the most intriguing thing about this photograph is the assortment of known individuals shown in it. The man with his head bandaged at the bottom right is Lt. Col. Tom Trevor, a British commando who accompanied the Ranger assault force as an observer. The man to the left of the radio antennae loading a magazine for his M1 Carbine is Lt. Elmer H. “Dutch” Vermeer, 2nd Ranger Battalion Engineer Officer. Official U.S. Navy photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives 80-G-45721

Another photograph showing Lieutenant Colonel Rudder’s command post at Pointe du Hoc’s eastern Type L409A antiaircraft bunker. Note the forty-eight-star U.S. flag being used to identify the position to ships offshore and aircraft overhead. German prisoners are being marched away under armed guard just above and to the left of the flag. National Archives and Records Administration 111-SC-190240

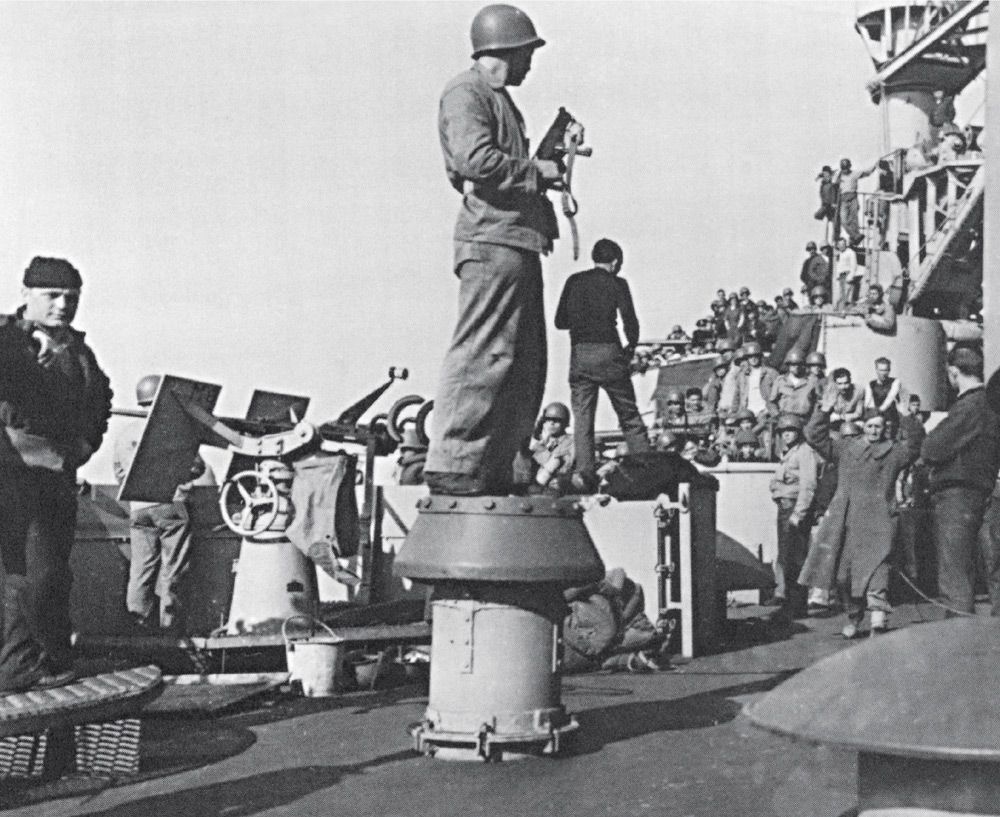

With a load of walking wounded Rangers from the Pointe du Hoc battle embarked aboard, LCM-81 pulls alongside a transport during the afternoon of June 6, 1944. For the first few days of the invasion, landing craft represented the only way to get supplies into and the wounded off of the point. Official U.S. Navy photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives 26-G-2368

Here, two Rangers have captured three German soldiers along with three Italian and four French laborers from Organisation Todt, the Third Reich workforce responsible for civil and military engineering projects. The laborers were at Pointe du Hoc to complete the two Type H679 casemates still under construction at the time of the invasion. LCVPs took twenty-seven prisoners off of the point on the afternoon of June 7, including the ten men seen here. National Archives and Records Administration 111-SC-190268

One of the French laborers captured at Pointe du Hoc is searched after being brought aboard the battleship USS Texas (BB-35) on the evening of June 7. He is being guarded by a member of the ship’s Marine detachment armed with a .45-caliber Reising Model 50 Submachine Gun. Although none of them went ashore on June 6, hundreds of U.S. Marines participated in the Normandy invasion.

Another scene on the deck of the Texas shows prisoners from Pointe du Hoc being brought aboard on D-Day. With dozens of the ship’s crew looking on, an Italian laborer comes forward under the watchful eye of a Marine armed with a .45-caliber Reising Model 55 Submachine Gun. The prisoners only remained on Texas briefly before being transferred to an LST.

The battery command and fire control/observation post (a Type R636a bunker) at Stützpunkt Pointe du Hoc (WN75) after the battle. A textured facade has been built around the structure in an effort to camouflage it. National Archives and Records Administration 111-SC-275839

One of the Type H679 casemates under construction at Stützpunkt Pointe du Hoc (WN75) when the Rangers landed on D-Day. National Archives and Records Administration 111-SC-275822

Both of the Type H679 casemates at Stützpunkt Pointe du Hoc (WN75) suffered heavy damage during the fighting on D-Day and the days that immediately followed. National Archives and Records Administration

One of the two Type L409A bunkers at Stützpunkt Pointe du Hoc (WN75). This position at one time mounted a 2cm Flugabwehrkanone 30 antiaircraft gun, but the weapon was removed because of the damage to the concrete. National Archives and Records Administration 111-SC-275825

In this June 10, 1944, aerial photograph of Pointe du Hoc, the heavy cratering from bombing and shelling is clearly in evidence.

A U.S. Army officer stands inside one of the craters at Stützpunkt Pointe du Hoc (WN75) after the battle. The width and depth of the crater clearly indicates the earthmoving power of the bomb that caused it. National Archives and Records Administration 111-SC-275840

This memorial to a fallen soldier stands amid the craters and debris of battle at Stützpunkt Pointe du Hoc (WN75). Here a U.S. M1 Helmet has been placed on top of the handgrip of a Vickers K Gun, the muzzle of which is stuck in the soil. Although they were British weapons chambered for the .303-caliber cartridge, K Guns were used during the battle at Pointe du Hoc mounted on the ends of extending ladders that were, in turn, mounted on DUKWs. A belt of German 7.92x57mm cartridges lies on a wooden crate in the foreground, and a spent U.S. M22 Colored Smoke Rifle Grenade is just above it. The K Gun’s drum magazine is in the dirt at the far right. Official U.S. Navy photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives 26-G-2441

Just a few days after D-Day, the 9th Tactical Air Command Signal Section set up camp in the orchard near La Montagne. During their time there, the men of this unit got a close-up look at the 155mm guns from Pointe du Hoc and sometimes even posed for photographs on them. Here, Pvt. Roy Vanderpolder and Pvt. Orville Iverson are sitting on one of the GPFs, which has been pulled from its firing position and deactivated by removal of its breechblock.

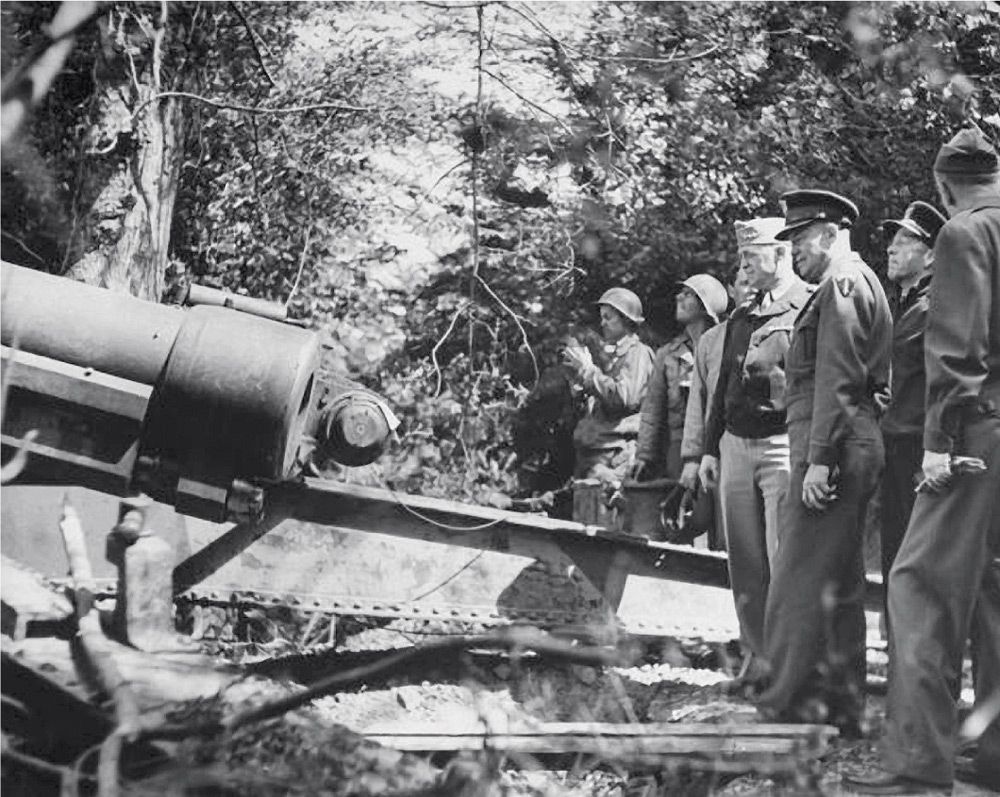

On Monday, June 12, 1944, a number of high-ranking U.S. military leaders visited the orchard at La Montagne to see the GPFs that had once armed Stützpunkt Pointe du Hoc (WN75). The officers in this photograph are Lt. Gen. Henry A. “Hap” Arnold, General Eisenhower, Adm. Alan G. Kirk, and (with his back to the camera) U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall. Note that the weapon’s breech is open and that wooden planks have been laid across the recoil pit beneath it.

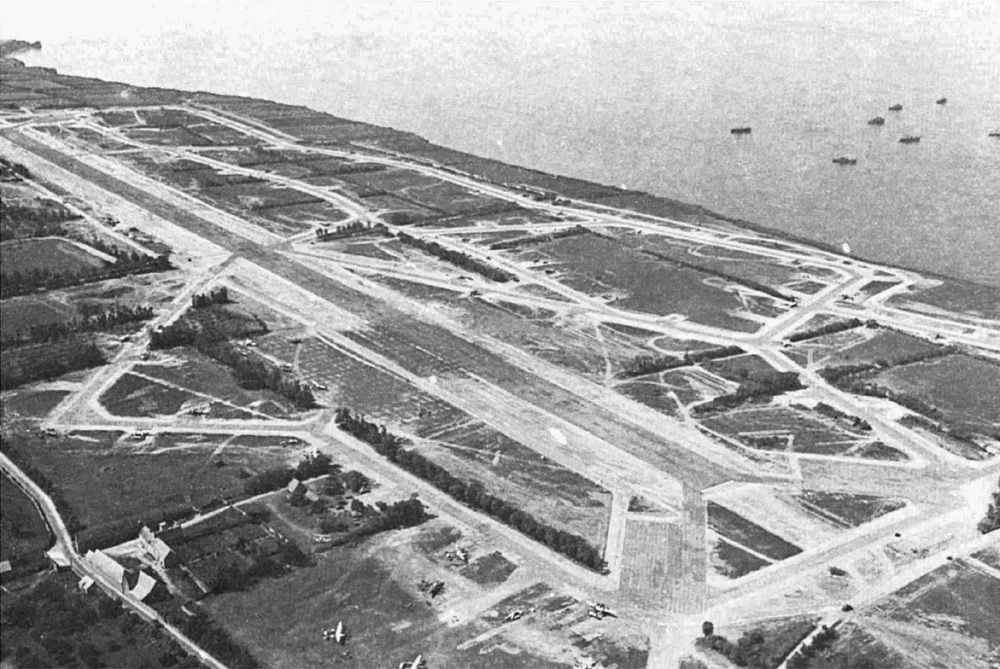

As soon as the corridor between Omaha Beach and Pointe du Hoc was secure, the 834th Engineer Aviation Battalion began building this temporary airfield parallel to D514 just east of Saint-Pierre-du-Mont. At first just an Emergency Landing Strip, then a Refueling and Rearming Strip, it ultimately became Advanced Landing Ground A-1 with a single five-thousand-foot SMT runway. Fighters, bombers, and transport aircraft made extensive use of A-1 before it was ultimately dismantled in September 1944. In this photograph of the airfield, Pointe du Hoc can be seen in the upper left corner, and P-38 Lightning fighters are parked in the field next to Ferme de Valmont, the cluster of buildings at the bottom left.

Lomell went back to Pointe du Hoc for the first time in 1964 with his wife, Charlotte, which is when he posed for this photograph in front of one of the site’s Type H679 casemates.

The same casemate has not changed much in seventy years.

Lomell ultimately received the Distinguished Service Cross for finding and disabling the Pointe du Hoc GPFs on D-Day, and he was eventually promoted to the rank of second lieutenant. Seen here at the end of the war, this citizen soldier finished his time in the Army a highly decorated Ranger and uniquely experienced combat leader. Lomell received his honorable discharge in December 1945, went to law school, and was admitted to the New Jersey Bar in 1951.

Lomell also posed on the stairs leading down into the troop shelter/ready ammunition storage area for one of the concrete traversing tables on the eastern side of Pointe du Hoc. In the foreground, the tip of the table’s pintle rod can be seen, and in the background is one of the site’s Type H679 casemates.

During his first return trip in 1964, Lomell paused to contemplate the spot where he scaled the cliffs at Pointe du Hoc twenty years earlier. With a long list of awards and accolades that ultimately brought him to the attention of celebrities, renowned journalists, and presidents, it is obvious that Lomell’s greatness was only getting started when he landed on this beach on D-Day. He passed away on March 1, 2011, of natural causes in Toms River, New Jersey.

Pointe du Hoc was chosen as the spot where Ronald Wilson Reagan, the fortieth president of the United States, would deliver his main address during the commemorative activities surrounding the fortieth anniversary of D-Day. From a podium on top of the Type R636a battery command/fire control post bunker, he set a bold, new tone for the U.S. memorialization of World War II with these words: “These are the boys of Pointe du Hoc. These are the men who took the cliffs. These are the champions who helped free a continent. These are the heroes who helped end a war.”

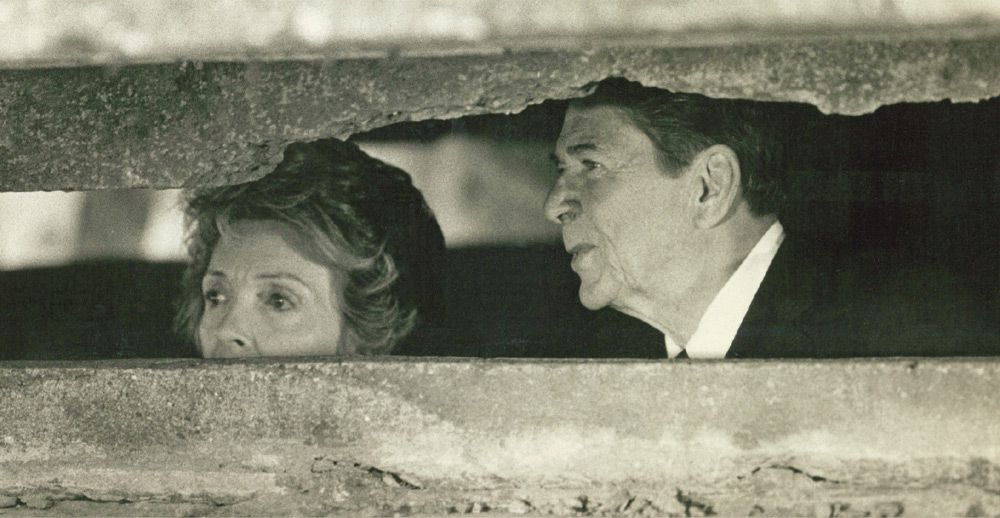

President Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan inside the telemetry room of the Type R636a battery command/fire control post bunker at Pointe du Hoc during their visit on the morning of June 6, 1984.

The Ranger Memorial on top of the Type R636a bunker at Pointe du Hoc looks out over an uncharacteristically calm Baie de la Seine on July 24, 2011.