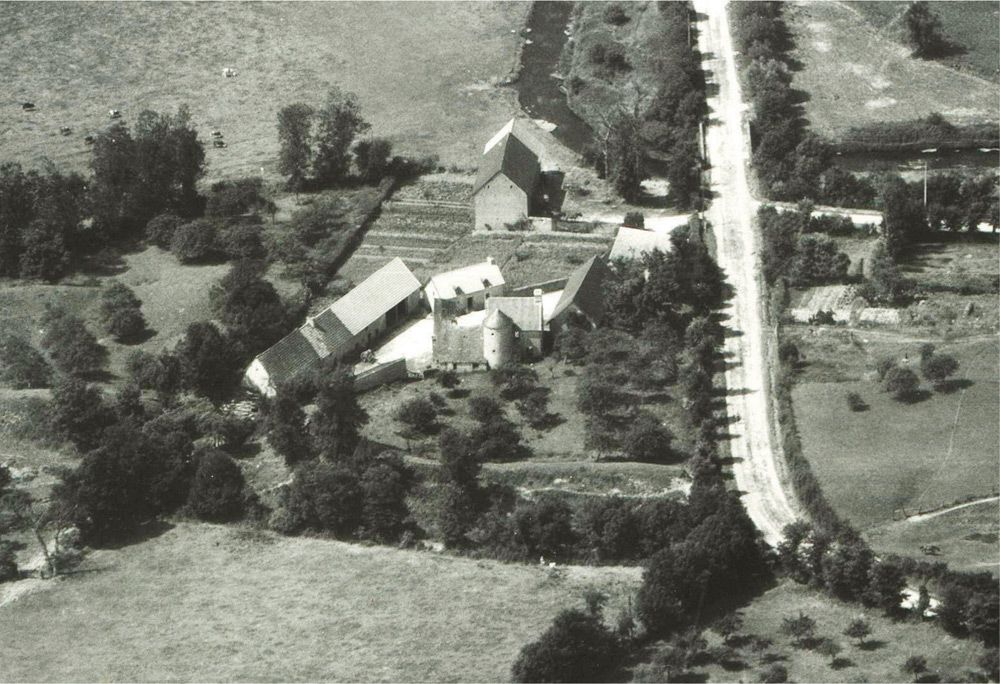

La Fière Manor and the D15 bridge over the Merderet River as seen from the air in June 2010. This small cluster of seven buildings became the scene of a vicious battle just after dawn on D-Day.

MANOIR DE LA FIÈRE is a small settlement of stone buildings just west of Sainte-Mère-Église that in June 1944 was owned by Monsieur Louis Leroux. Because of its strategic location astride the Merderet River, the manor was one of the primary D-Day objectives of Maj. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway’s 82nd Airborne Division. Normally little more than a narrow, meandering creek, the Merderet’s condition was far from normal in June 1944. It had transformed into a huge, shallow lake 3/5 of a mile wide by 6 1/4 miles long. The virtually impassable inundated area produced by the flood-stage river separated the Amfreville/Motey area to the west from the city of Carentan and the villages of Chef-du-Pont and Sainte-Mère-Église to the east.

La Fière Manor and the D15 bridge over the Merderet River as seen from the air in June 2010. This small cluster of seven buildings became the scene of a vicious battle just after dawn on D-Day.

This aerial view of the area surrounding the La Fière causeway shows the following: 1. La Fière Manor, 2. the Merderet River Bridge at La Fière, 3. La Fière causeway, 4. the chapel at Cauqigny, 5. Hameau aux Brix, and 6. Les Heutes/Timmes’ Orchard.

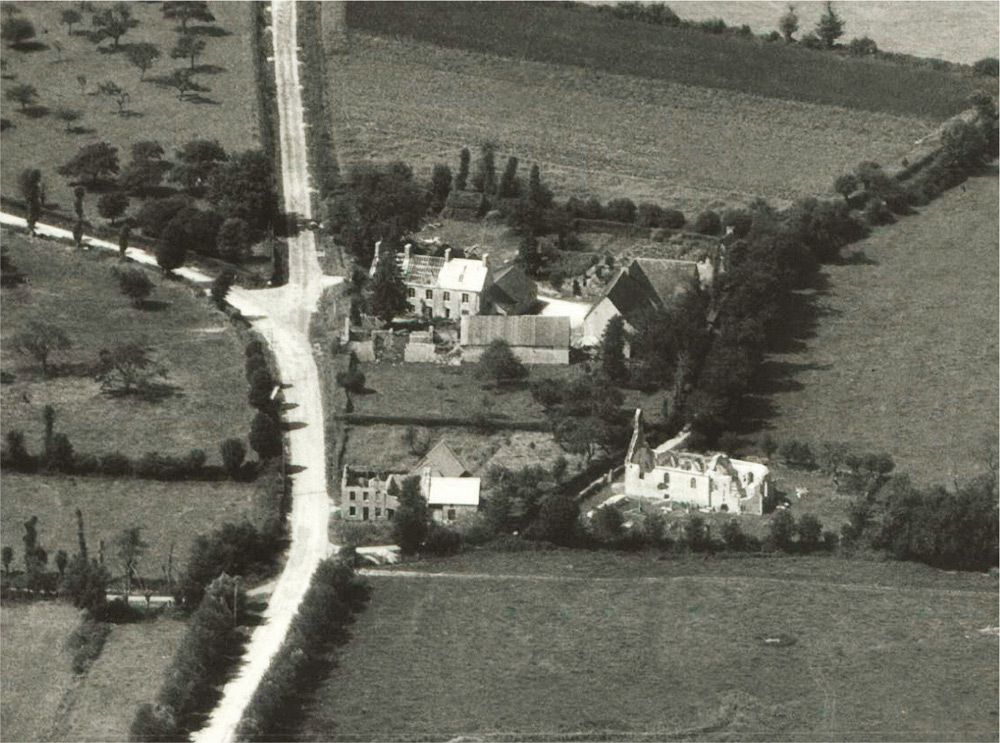

Seen here in 1946, La Fière Manor still shows signs of the damage it sustained during the fighting in June 1944. The roof of the southern half of the main house is almost completely missing. Note that the Sainte-Mère-Église/Amfreville road (now D15) was not paved back then.

The U.S. invasion plan called for the establishment and then the expansion of a beachhead at La Madeleine on the east coast of the Cotentin Peninsula, followed by a drive north toward Cherbourg. For the U.S. Army VII Corps—the force tasked with establishing that beachhead—the swollen condition of the Merderet River would present a difficult obstacle. With infantry and mechanized units pouring across Utah Beach, the road networks leading into the interior of the Cotentin and across the Merderet would be strategically crucial.

The 82nd Airborne’s three parachute infantry regiments had each been given mission objectives in the Sainte-Mère-Église area during this operation. According to this plan, the 508th Parachute Infantry would capture the Douve River crossings to the southwest. The 505th Parachute Infantry would take Sainte-Mère-Église itself, as well as the eastern ends of the Merderet River crossings at Chef-du-Pont and La Fière. By dropping near Amfreville, the 507th Parachute Infantry would be in a position to capture the western end of the La Fière causeway: the tiny village of Cauquigny. There, an elevated roadway stretched five hundred yards across the inundated Merderet basin to La Fière on the east bank. Holding Cauquigny, La Fière, and the causeway stretching between them would give the U.S. Army VII Corps back at the beach the open artery over the swollen river it needed. Failure to secure the Merderet River crossings could spell disaster for VII Corps. Taking Sainte-Mère-Église, Chef-du-Pont, and the bridge and causeway at La Fière during the first hours of the invasion was of the utmost importance.

Manoir de la Fière suffered extensive damage during the fighting that took place around it between June 6 and 9. This photograph provides evidence of the pounding the manor’s main house received.

Inconveniently, twenty-eight German infantrymen arrived at Manoir de la Fière at 11 p.m. on Monday, June 5, to establish an outpost. Roused out of bed, Monsieur Leroux and his family were surprised by their arrival because, strangely, no German soldiers had ever occupied the manor before. Thus, as the men of the 82nd Airborne were being flown across the English Channel during the predawn hours of D-Day, the German soldiers they would soon face at La Fière were just beginning to settle in and prepare their defenses, setting the stage for battle.

The mission that dropped the 82nd Airborne Division on June 6, 1944, was codenamed “Boston,” and it did not go perfectly according to plan in the skies above the Cotentin. As the 378 C-47s carrying the division’s three parachute infantry regiments approached their drop zones, they encountered thick cloud cover and German antiaircraft fire. The combination of low visibility and flak produced a scattered drop. Out of the three regiments, the 505th was the luckiest, with most of its sticks coming down between Sainte-Mère-Église and the Merderet. The 508th and 507th did not experience similar fortune. Many of the 508th sticks ended up west of the river in the vicinity of Picauville and Pont-l’Abbé, while a large number of 507th sticks were dropped east of their drop zone in the inundated area of the Merderet River. Most of the paratroopers who landed there were driven by instinct toward the dry ground closest to them, which just so happened to be the Carentan/Cherbourg railroad embankment. Once there, they followed the embankment south to its junction with the road to Sainte-Mère-Église (present-day D15), and from there, La Fière Manor sat only eight hundred yards to the west along good road. Since La Fière Manor was one of the division’s main objectives, several groups of the 82nd Airborne’s paratroopers began moving toward it during the predawn hours of D-Day.

The central yard of La Fière Manor as seen from the second floor of the main house. Outbuildings in this photograph include the stable, barn, and mill. The Merderet River Bridge, which is mostly obscured by bushes to the left of the white gate, is at the center; beyond that, the causeway can be seen as it bends toward the northwest. The stone building in the distance at the center is the chapel at Cauquigny 2,053 feet (625 meters) away.

The Merderet River Bridge at La Fière as it appeared in July 1944 when army historian S.L.A. Marshall visited the site shortly after the battle. Note the rough condition of the road surfacing and the concrete telephone pole. The distance from the main house at La Fière Manor to the bridge is barely one hundred feet.

The opening shots of the battle for La Fière were fired at dawn when an MG42 in the manor’s main house opened on troopers of Lt. John J. “Red Dog” Dolan’s A Company, 505th Parachute Infantry. The twenty-eight German soldiers who had arrived to occupy the manor the night before were not going to give up without a fight. Dolan’s 505th troopers then attempted to flank the enemy by maneuvering around to attack the right (or north) side of the manor. In so doing, they ran into more small-arms and machine-gun fire. A force of eighty 507th paratroopers being led by G Company Commander Capt. “Ben” Schwartzwalder then joined the battle. What was developing at La Fière Manor that morning was a fight in which several units simultaneously converged on the same objective in a piecemeal, uncoordinated manner. Captain Schwartzwalder had his men cross the road and enter the fields on its south side. Once in the fields, they began moving cautiously toward their objective.

La Fière Manor was surrounded by mainly pasture on its western side, with orchards and earthen mounds to the east. A vast network of crisscrossing hedgerows dominated its eastern approaches from the direction of Sainte-Mère-Église—the area through which the 82nd would have to fight. After moving only a short distance, Schwartzwalder’s group came under fire from a German machine gun in the manor—one of the same machine guns that had stopped Dolan’s 505th paratroopers earlier in the morning. At about that same time, 508th regimental commander Col. Roy Lindquist arrived on the scene with a group of troopers that included men from C Company, 505th. With a minimum of coordination, these units continued to converge until elements of the 505th and the 508th began to enter the manor grounds through the backyard. Sporadic return fire continued briefly until one of the A Company, 505th men advancing with Dolan pulled the trigger on his M1A1 Bazooka rocket launcher and a 2.36-inch rocket slammed into the stoutly built stone house. Then a 508th sergeant by the name of Palmer darted through the front door and emptied a full magazine from his Thompson submachine gun up through the floorboards of the second story. What was left of the German force surrendered at that point, and the battle for the Leroux manor at La Fière was over.

This Marshall photograph, taken from the middle of the Merderet River Bridge at La Fière, looks west toward Cauquigny. Compared to the way the same spot looks today, there was much more foliage present along the causeway in 1944.

Looking northeast from the middle of La Fière bridge, these photographs show that very little has changed since Marshall took the top photograph seventy years ago. In the modern photograph, the church at Neuville-au-Plain can be seen 2.5 miles in the distance, but it is obscured by dense foliage in the 1944 photograph.

A mere 75 feet in length, the old stone bridge at La Fière became critically important at the outset of the invasion because it, along with the 1,500-foot-long causeway leading beyond it to Cauquigny, offered one of only two crossing points of the flooded Merderet River.

Meanwhile, on the other end of the causeway, Lt. Col. Charles J. Timmes, commanding the 2nd Battalion of the 507th, was in an difficult position. He had landed on the correct side of the river with a group of men, but he could not establish communications with either his regiment or his division. Rather than move his force over to the east bank of the Merderet, Timmes placed his men in defensive positions at an apple orchard northeast of Le Motey at Les Heutes. He knew that he needed to occupy the western end of the La Fière causeway, so he ordered Lt. Louis Levy to take ten men and outpost the village of Cauquigny. When Levy’s patrol arrived there around noon, they found Cauquigny clear of the enemy.

Tanks of Panzer Ersatz und Ausbildungs Abteilung 100 (100th Tank Replacement and Training Battalion) knocked out during the intense fighting that unfolded on the La Fière causeway. All three of the vehicles seen here are French-made tanks that were captured in 1940: at the far left and far right are examples of the Renault R35, which was designated Panzerkampfwagen 35R 731(f) in German service. The tank in the center is a Hotchkiss H38/39, known as Panzerkampfwagen 38H 735(f) to the Germans. The section of track in the foreground belongs to the only German-made Panzerkampfwagen III Sonderkraftfahrzeug 141 in the battalion’s inventory. This image was taken from a reel of motion-picture footage filmed by Signal Corps photographer T-4 Reuben A. Weiner of the 165th Signal Photo Company on June 10, 1944.

La Fière, Cauquigny, and the roadway stretching between them now belonged to the 82nd Airborne Division. Captain Schwartzwalder felt that the time was right for his force to cross over to the west bank and join the force at Timmes Orchard. When the company reached the west bank, Schwartzwalder left Lieutenant Levy and eight men to guard Cauquigny and then moved out in search of Lieutenant Colonel Timmes. At La Fière, paratroopers of the 505th dug in and prepared to defend the manor. Two bazooka teams positioned themselves near the bridge and dragged a disabled German truck into the middle of the causeway to act as a roadblock. Finally, the paratroopers positioned a 57mm antitank gun directly at the bend in the road above the manor, overlooking the causeway.

Aware of what was at stake at the La Fière crossing of the Merderet area, the Germans had already dispatched forces on the west bank to counterattack toward Cauquigny and the American bridgehead beyond. Soon, elements of the German 91 Luftland Division appeared west of Cauquigny, bearing down on the causeway. This force consisted of a rifle company from Grenadier Regiment 1057 and elements of Panzer Ersatz und Ausbildungs Abteilung 100 (100th Tank Training and Replacement Battalion), an armored training battalion equipped with mostly French-made Renault and Hotchkiss light tanks. With a Panzerkampfwagen III Sd.Kfz. 141 leading the column, the tanks and infantry quickly rolled over Lieutenant Levy’s lightly armed force guarding Cauquigny in a skirmish that lasted only ten minutes. At that point, the Germans pushed onward across the causeway.

At approximately 5 p.m., the full weight of the armored counterattack fell on the paratroopers of Lieutenant Dolan’s A Company, 505th in their positions around the bridge at La Fière. In the savage fight that followed, the Americans employed an M1A1 Bazooka and the lone 57mm antitank rifle to knock out the Panzerkampfwagen III and two French tanks. Then, concentrated fire from the paratroopers’ M1 rifles and especially their .30-caliber machine guns tore viciously into the infantry exposed on the open road. Soon, the energy of the assault had been drained, and the Germans withdrew, having sustained heavy casualties.

This image from the Marshall series shows the bend in the La Fière causeway where so much intense combat unfolded on June 6 and 7 as elements of Panzer Ersatz und Ausbildungs Abteilung 100 and Grenadier Regiment 1057 attempted to recapture the La Fière causeway. The concrete telephone poles are gone now, and the foliage is not as thick, but the site remains easily recognizable nevertheless.

Private Marcus Heim of A Company, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division receives the Distinguished Service Cross from Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley in La Haye-du-Puis on July 1, 1944. When the tanks attacked La Fière on D-Day, Private Heim was an assistant gunner with one of the bazooka teams defending the Merderet River Bridge. Since their fighting position was below the road behind a telephone pole, the two men were forced to stand when firing. Even when the tanks approached to within thirty yards, Heim remained with his gunner, Pfc. Lenold C. Peterson, reloading the rocket launcher as rapidly as possible. At first, branches obscured their field of fire, so the two paratroopers moved forward to continue fighting. In the middle of the battle, they ran out of rockets, forcing Private Heim to run from one side of the causeway to the other under fire to retrieve more from another position. Together, they put rockets into all three of the tanks, thereby helping to repulse the attack. For this, both men were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Today, the causeway is named Voie Marcus Heim in his honor.

Although this photograph was taken on August 7, 1944, it shows a dump where U.S. forces collected some of the captured French tanks used by the Germans in Normandy. Recognizable here are four Renault R35s, eight Hotchkiss H39s, and an old Renault FT (the tenth tank from the left with the domed commander’s cupola). These vehicles are from Panzer Ersatz und Ausbildungs Abteilung 100 and Panzer Abteilung 206, another tank unit based on the Cotentin Peninsula. The eighth vehicle—which can easily be picked out of the lineup by its distinctive long gun barrel equipped with a muzzle brake—is a Marder III Ausführung H, Sonderkraftfahrzeug 138, a tank destroyer produced by mounting the 7.5cm Panzerabwehrkanone 40 on the chassis of the pre-war Czech-designed Panzerkampfwagen 38(t). In all likelihood, the Marder was assigned to SS Panzerjäger Abteilung 17 of the 17 SS Panzer Grenadier Division.

These soldiers of the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division have set up a position for an M1919A4 Machine Gun at the base of a typical Norman hedgerow. Throughout the Normandy campaign, both sides used the mounds upon which hedgerows grew as defensive positions. There are eight cans of belted .30-caliber ammunition in this photograph, equaling a total of two thousand rounds for the M1919A4. The man with his back to the camera is wearing an unusual ensemble: an M1941 Field Jacket, M1942 jump trousers, and rough-out service shoes with leggings—a mix of paratrooper and regular infantry uniform items.

The next morning (D+1), the Germans threw another combined assault at the paratroopers defending La Fière Manor. This time, the thrust was preceded by heavy supporting fire from mortars and artillery that had been brought in overnight. Just as the day before, the attack advanced as far as the outermost American defensive positions before grinding to a halt. The lone 57mm antitank gun knocked out the lead tank, after which German infantrymen swarmed forward. At point-blank range, the enemy tossed grenades and poured a relentless fire into the paratroopers using Mauser rifles and MP40 submachine guns. The men of Dolan’s A Company, 505th at the foot of the bridge faced the full weight of the German assault, and the combat grew ferocious. But then the brutal attack mysteriously ended. The German infantry that had advanced almost to the bridge melted back toward Cauquigny in a fighting withdrawal. Although the paratroopers had survived another German onslaught, the situation at the causeway remained a stalemate, and the great, decisive battle was yet to be waged.

In addition to the big guns of the 345th Field Artillery Battalion, the 82nd Airborne Division’s mortars also contributed to the preparatory bombardment on Cauquigny on June 9. In this photo, an M1 81mm mortar team from the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment fires from a pit dug in the hedgerows near La Fière.

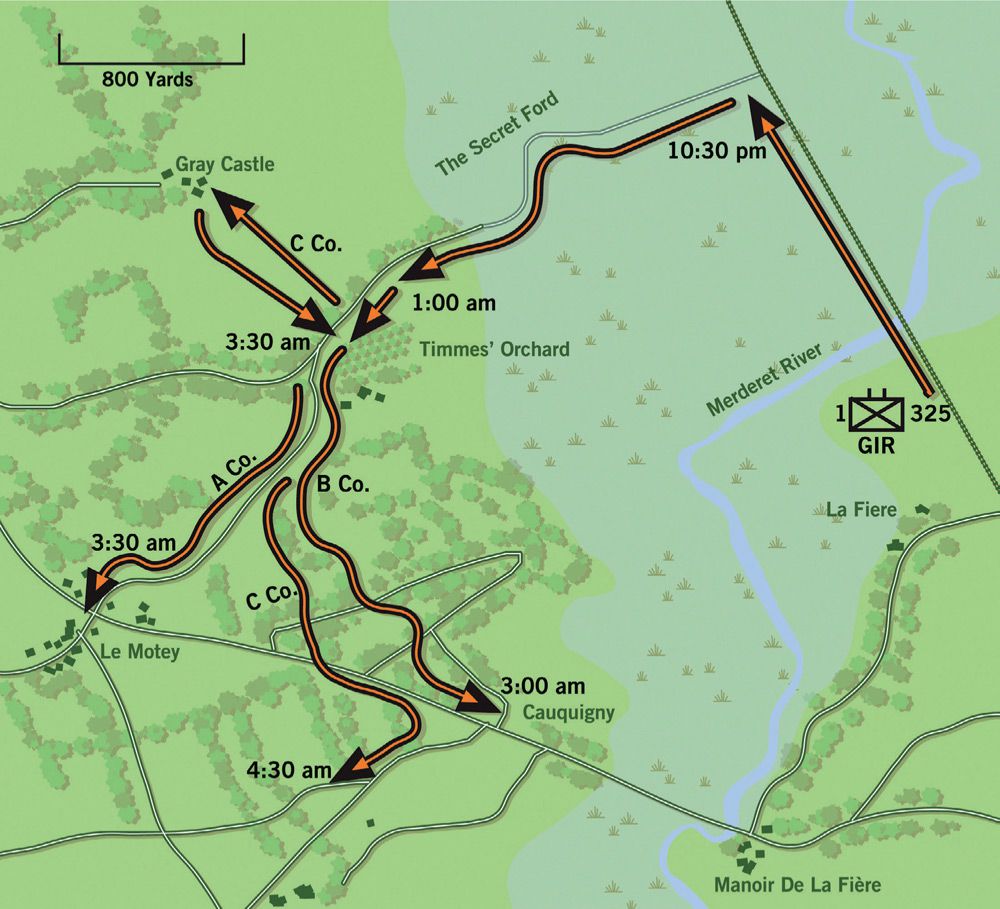

The 82nd Airborne soldiers at La Fière remained under almost constant artillery and mortar fire throughout the day on June 8, but the Germans made no further attempts to get vehicles or infantry across the causeway. Later in the day, it was decided that, to break the stalemate, elements of the division would cross the inundated area just north of La Fière. The force drawing this responsibility would be Maj. Teddy H. Sanford’s 1st Battalion, 325th Glider Infantry Regiment. The 325th had come in by glider beginning at 7 a.m. on D+1 (June 7) and had not yet been committed to heavy action. According to the plan, the 1st, 325th would attempt to reinforce the paratroopers isolated at Timmes’ Orchard and attack south toward the western terminus of the La Fière causeway at Cauquigny. The men of the 1st, 325th crossed the flooded Merderet during the predawn hours of June 9 using an old cobblestone road referred to as “The Secret Ford.” After making contact with Lieutenant Colonel Timmes’ force, the glider infantrymen began their assault before first light, despite drawing fire from German soldiers in the so-called “Gray Castle,” a chateau near the village of Amfreville. Moving south from the perimeter at the orchard, the battalion at first advanced steadily toward the north side of Cauquigny against sporadic resistance, but as the sun began to rise, the defenders quickly organized themselves. The German counterattack that followed overwhelmed the glidermen by sheer numbers. With concentrated automatic-weapons fire directed at them, the 325th could not maintain the momentum of the advance and began a strategic withdrawal back toward Timmes’ Orchard.

When word of the failure of Major Sanford’s attack on the west bank reached Major General Ridgway, 82nd Airborne Division Commanding General, he ordered a direct assault across the La Fière causeway and appointed his assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. James M. Gavin, to organize it. Gavin selected the 3rd Battalion, 325th Glider Infantry to serve as the spearhead of the attack and designated a composite company of 507th paratroopers to serve as the follow-up reserve force in the event that things went wrong for the glidermen. Leading this composite force was Capt. Robert D. Rae of Service Company, 507th.

At 10:30 a.m. on June 9, the plan was set in motion when six 155mm howitzers of the 345th Field Artillery Battalion commenced a preliminary bombardment that pounded German positions on the west bank of the Merderet. After fifteen minutes, the 155mm fire lifted, and the infantry charged in. Leading the way was Capt. John Sauls’ G Company, 325th, which jumped off from a low stone wall running along the south side of the road perpendicular to the bridge and causeway. Sauls and his men ran out onto the open roadway and started down the long five hundred yards to Cauquigny. As soon as the preliminary bombardment lifted, the Germans began pouring small-arms fire into the exposed and vulnerable glidermen. Captain Sauls and a group of about thirty men made it all the way to Cauquigny, but others were not so fortunate. Lacking cover, the men of E Company, 325th and F Company, 325th began to fall, and the causeway was soon littered with the dead, the dying, and the wounded. The German machine-gun fire was of such intensity that many of the men gave in to the temptation to seek shelter along the edges of the elevated road. As the gliderman of G Company stumbled forward, stepping over the casualties scattered along the road, the assault began to bog down and lose its momentum.

Private First Class Charles N. DeGlopper of C Company, 325th Glider Infantry Regiment. During the abortive predawn assault on Cauquigny on June 9, DeGlopper walked out into the middle of Route du Hameau Flaux (present-day D15), 1,500 feet west of Cauquigny, and sprayed enemy positions with bullets from his M1918A2 Browning Automatic Rifle. Although this action provided the necessary covering fire for the withdrawal of the rest of his squad, German bullets ultimately struck DeGlopper down. He sacrificed his life to save the other members of his squad and was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for doing so. National Archives and Records Administration 111-SC-313653

Back at La Fière, it was not apparent that any elements of the 325th had made it to Cauquigny. General Gavin could only assess the situation based on what he could see, which was not encouraging. What he could see was dozens of motionless soldiers crouching along the road embankment seeking cover and dozens of dead and wounded men sprawled out in the middle of the causeway. He could not see the small groups of men struggling to hold the bridgehead. Although the situation at Cauquigny was indeed critical, to General Gavin back at La Fière, it seemed absolutely disastrous. To him, it appeared that the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment’s attack had stalled and that the entire battalion was about to retreat. That is when General Gavin turned to Rae and said, “All right, you’ve got to go.”

With that, Captain Rae led his men out onto the La Fière causeway. The company streamed across the bridge in two columns with Rae in the lead at a full sprint. As the 507th troopers passed glidermen from E Company and F Company of the 325th, they shouted to them to follow. Most of Rae’s men made it all the way across and joined the 325th troopers struggling in the hedgerows at Cauquigny. The sudden arrival of Rae’s company and additional 325th troopers changed the tide of the battle. Soon, the Germans were pulling back from Cauquigny in a fighting retreat toward Le Motey and Amfreville. The causeway now belonged to the 82nd Airborne Division, and the battle of La Fière had been won.

Brigadier General Gavin, the Assistant Division Commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, talks with Col. Harry L. Lewis, Commanding Officer of the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment near Etienville on June 14, 1944. These two men played central roles in the battle that unfolded over the causeway on June 9. On the left is Lt. Hugo Olson, General Gavin’s aide.

This map shows the movement of the 1st Battalion, 325th Glider Infantry Regiment during its predawn flanking maneuver on June 9, 1944. The battalion started off by proceeding north along the Carentan–Cherbourg railroad line to its crossing of the Merderet River. From there, the men continued another half mile to the point where the railroad intersects with the old Roman road running from Neuville-au-Plain to Amfreville. Known as “The Secret Ford,” this cobblestone path allowed all three of the battalion’s companies to cross the inundated area in only ankle-deep water. Upon reaching Timmes’ Orchard, part of the battalion attacked the German outpost at the Gray Castle, while A, B, and C Companies pushed south to isolate Cauquigny and outflank the western end of the La Fière causeway.

Located two thousand feet northwest of Timmes’ Orchard, this is the château that was outposted by German troops from Grenadier Regiment 1057. Because of the two turreted towers that stand on either side of the château’s entrance, the men of the 82nd Airborne nicknamed the structure the “Gray Castle.”

The ruins of Cauquigny can be seen in this photograph taken by Army historian S.L.A. Marshall shortly after the battle of the La Fière causeway.

An aerial view of Cauquigny taken after the end of the war showing the heavy damage the tiny village sustained during the June 1944 battle.

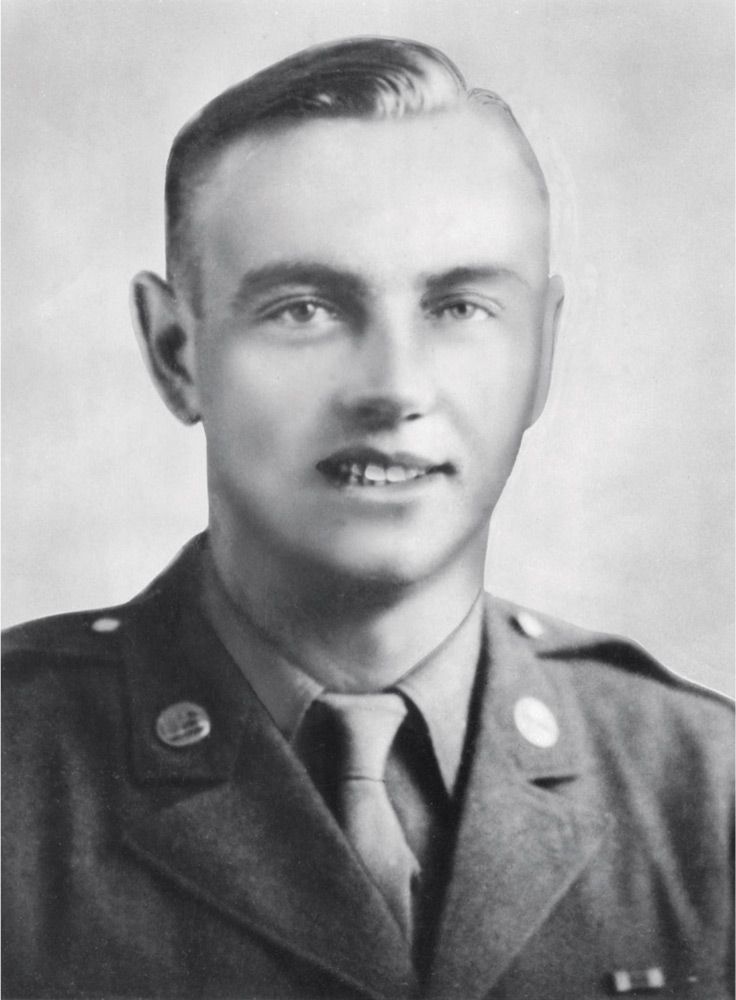

Robert Dempsey Rae of Service Company, 507th as a lieutenant in 1943. Rae jumped into Normandy as a captain on D-Day and earned the Distinguished Service Cross three days later on the La Fière causeway.

Looking westward down the length of the La Fière causeway (present-day D15) toward Cauquigny in a view that clearly shows how the road surface is raised above the surrounding fields. Just before the invasion, the swollen Merderet River had flooded the lowlands on either side of the causeway, making it one of only two crossing points for the U.S. Army’s VII Corps. When the morning attack on June 9 began to stall, soldiers from E and F Companies, 325th Glider Infantry sought cover along the edges of the causeway. The chapel at Cauquigny can be seen in the distance to the right of the road.

The guns of the 345th Field Artillery Battalion provided the punch behind the bombardment that preceded the attack across the La Fière causeway on June 9. Here, one of the battalion’s M1 155mm howitzers is in its firing position in a field near La Fière.

Private James Schaffner of the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment poses in front of the east side of the heavily damaged chapel at Cauquigny. This photo was taken on the afternoon of June 9 after the battle had already flowed toward Le Motey. The same chapel, following repairs after the war, looks much better today.

Private Schaffner (left) and Pvt. Gerald W. Arnold (right) of the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment pose on the west side of the chapel at Cauquigny on June 9. The location looks much the same today.

The intense fighting around Cauquigny left damage that can still be observed now. Here, a U.S. .30-caliber bullet remains lodged in one of the wrought-iron bars that enclose a grave in the chapel’s cemetery.