8

AFTERMATH

The Storm

On June 19, 1944, the worst storm in forty years struck Normandy and pounded the coast for three days, finally abating on June 22. With heavy rain, howling wind, and violent surf, this massive storm system damaged both of the temporary Mulberry harbors the Allies had built to support landing operations. The British Mulberry Harbor at Arromanches, nicknamed “Port Winston,” sustained light damage, but it was ultimately repaired and continued to serve. The American Mulberry Harbor on Omaha Beach at Vierville-sur-Mer, on the other hand, sustained such heavy damage that it could not be repaired. Everything that came ashore in the American sector from that point onward was landed across the open beach by LSTs and other landing craft. A sobering point about this storm relates back to General Eisenhower’s decision to postpone the invasion from June 5 to 6. Some of the officers on the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force staff felt that the safer bet would be to wait until later in the month. Had General Eisenhower elected to postpone the invasion by three weeks instead of twenty-four hours, the landings would have occurred during this storm with potentially catastrophic results.

These Germans are not actually German but Polish volunteers captured near Utah Beach being guarded by sailors from the 2nd Naval Beach Battalion on June 15, 1944. The sailor on the left is armed with an M1903 rifle. The older prisoner is wearing M42 ankle boots and leggings (what the Germans called schnürschuhe und gamaschen), while the younger one wears hobnailed Model 1939 jackboots (knobelbecher). U.S. Navy photograph, now in the collections of the U.S. National Archives 80-G-253030

This photograph of Omaha Beach was taken in the vicinity of the Ruquet Valley/Exit E-1 looking to the east down the length of the Easy Red sector during the third week of June 1944. A large assortment of military equipment can be seen on the shingle in this view, including a Bantam T-3 trailer and several beached LCVPs. In the center, LCT-1035 is easily identified by the distinctive paint scheme and hull markings unique to the Royal Navy.

This view shows low tide at the Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach in front of the Ruquet River Valley. Here, the cameraman is facing to the northwest and has captured beach obstacles, landing craft, a pair of U.S. Army small tugs, and “corncob” blockships of “Gooseberry 2” for the American Mulberry Harbor (in the background). There are two LCVPs from the Crescent City–class attack transport USS Charles Carroll (APA-28) in the foreground, one sitting on its keel and the other upturned.

Not a Harbor, But a Field of Ruins

The U.S. Army’s VII Corps, comprising eighty thousand men, was given the mission of landing on Utah Beach, attacking toward and eventually capturing the sprawling port facility at Cherbourg. After cutting off the Cotentin Peninsula on June 16, VII Corps forces turned to the north and began pushing toward the city, with the 9th Infantry Division, the 79th Infantry Division, and the 4th Infantry Division as the spearhead. Some German commanders wanted to withdraw fighting forces from Normandy to mount a more effective defense of occupied France, but Führer und Reichskanzler Adolf Hitler rejected that proposition in his meeting with Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt and Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel at the Führerhauptquartier Wolfsschlucht 2 in the city of Margival, France, near Soissons on June 17. In that meeting, Hitler instructed the commander of German forces in Cherbourg, Generalleutnant Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben, to hold out, “Even if worse comes to worst.” He went on to instruct von Schlieben with these fateful words: “It is your duty to defend the last bunker and leave to the enemy not a harbor but a field of ruins. … The German people and the whole world are watching your fight; on it depends the conduct and result of operations to smash the beachheads, and the honor of the German Army and of your own name.” The U.S. attack on the city began on June 22 with a massive aerial and artillery bombardment. The fighting continued on the 24th, and von Schlieben dutifully passed on Hitler’s instruction “defend to the last cartridge” to his garrison force. On June 25, a massive naval bombardment made it possible for the Americans to enter the downtown waterfront area. On June 26, soldiers from the U.S. 39th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division captured von Schlieben himself in the city’s Saint-Sauveur neighborhood, marking the end of organized opposition. Although the harbor forts and the old French naval arsenal did not surrender until June 29, the battle was over. U.S. forces had seized the port and captured thirty thousand German troops.

A dead U.S. soldier lies on the shingle in front of the Les Moulins Draw/Exit D-3 on the Easy Green sector of Omaha Beach on Wednesday, June 7, 1944. The three-story house behind him is Villa les Sables d’Or, which provided cover the day before for a fifty-man force under the command of Major Bingham, commander of the 2nd Battalion, 116th Infantry Regiment. The cleanup of Omaha Beach has not yet begun at this point, and the dead still litter the battlefield.

The body of a young U.S. Army soldier lies face down in the sand at the base of an obstacle on Omaha Beach. He was killed during the intense fighting in front of Vierville-sur-Mer on D-Day, and the tide carried his body to the Dog White sector overnight, where this photograph was taken during the morning low tide on Wednesday, June 7, 1944. The fact that he is wearing M1942 HBT trousers and an M1941 Field Jacket suggests that he was a Ranger either from the 2nd or 5th Battalion. He still wears his M1926 Inflatable Lifebelt, and two weapons lay in the sand at his feet: one is an M1 Garand semiautomatic rifle, and the other is an M1903 Springfield bolt-action rifle. He was just one of the almost nine hundred soldiers of the U.S. Army’s V Corps to lose his life during the battle of Omaha Beach. U.S. Coast Guard Collection in the U.S. National Archives 26-G-2397

Another GI who did not survive the battle of Omaha Beach is seen here during the morning low tide on June 7. He still wears his M1926 Inflatable Lifebelt, an M7 Assault Gas Mask Bag, an M1941 Field Jacket, and M1937 Olive Drab Wool Field Trousers. A wedding ring is on his left ring finger, so a young woman back home became a widow on D-Day.

Dodge WC-54 3/4-ton ambulances from the 546th Medical Ambulance Company land on the Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach from LCT-550 on Monday, June 12, 1944. The lead ambulance is equipped with an extended air intake/snorkel for fording deep water. The 546th was one of the most important companies supporting the U.S. Army’s XIX Corps during combat operations in Normandy. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-191168

Saint-Lô

After establishing the beachhead in the American sectors of the invasion area, the U.S. First Army moved on to the next phase of operations. This called for three U.S. Army corps to push south from Carentan as part of the drive to continue expanding the beachhead. Directly in the path of the Army’s XIX Corps was the crucially important crossroads town of Saint-Lô. As the Germans began to recover and reorganize in the aftermath of the June 6 landings, they established a heavily reinforced line of resistance just north of the city that made use of terrain favoring the defense. The principal terrain feature encountered there was known as bocage to the French and simply as “hedgerows” to the American soldiers who had to fight among them. When the XIX Corps approached Saint-Lô at the beginning of July, it quickly bogged down before the difficult terrain and the stiff resistance. The fighting that followed included intense artillery duels and carpet-bombing that destroyed as much as 95 percent of the city. The extent of the damage earned Saint-Lô the unenviable nickname “The Capital of the Ruins.”

German Army soldiers from 709 Infanterie Division come forward to surrender on June 9 at Taret de Ravenoville, five miles up the coast from Utah Beach. The eastern shore of the Cotentin Peninsula south of Quinéville was cleared by troops of the 22nd Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division and the 39th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division during the first week of the invasion. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190259

With U.S. forces brought to a standstill in front of Saint-Lô toward the end of July, a general breakthrough in the area was needed. Accordingly, an operation named Cobra was planned for the area immediately west of the city for July 24. Before Cobra’s kickoff, though, a corridor just north of the towns of Saint-Gilles and Marigny was carpet-bombed in order to weaken the German defensive lines in front of the U.S. 30th Infantry Division. Although bombs accidentally fell on friendly positions, even resulting in the death of Lt. Gen. Lesley J. McNair on July 25, the carpet-bombing successfully opened a gap in the German lines. The U.S. 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions then pushed southwest from the Saint-Lô area with such swiftness that the Germans were caught off balance. By July 31, the U.S. Army’s XIX Corps had destroyed the last forces opposing Bradley’s First Army. Finally freed from the hedgerows, once American mechanized units began moving quickly, they were practically unstoppable. Operation Cobra transformed the bogged-down, attritional infantry combat of Normandy into the rapid, maneuver warfare that eventually led to the creation of the Falaise Pocket.

Troops from the 4th Infantry Division lead German Army soldiers from 709 Infanterie Division to a prisoner-of-war enclosure on Utah Beach on June 6, 1944. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190463

Mortain

Following the breakout’s success, units of the U.S. First Army streamed southward toward the city of Avranches. On August 1, General Patton’s Third Army went into action for the first time and began to operate in the area south of the city, but the U.S. Army held only a very narrow corridor. In an attempt to cut off Patton’s Army, Hitler personally ordered a counteroffensive to sever the corridor linking the Third Army with Allied forces to the north. Called Operation Lüttich, this German attack called for the XXXXVII Panzerkorps (47th Panzer Corps) to push west from the area around the city of Mortain toward Avranches. If they could recapture Avranches, they could trap the Third Army and trigger an American retreat. Consisting of one and a half SS Panzer Divisions and two German Army Panzer Divisions, the Lüttich assault force began to advance on August 7. The 2 SS Panzer Division “Das Reich” moved so swiftly at first that it easily surrounded the 2nd Battalion of the U.S. 120th Infantry Regiment on Hill 314 near Mortain. By August 13, Allied air strikes had taken their toll on the German advance, and they had been driven back with the loss of 150 tanks. The German counteroffensive had failed to stem the U.S. advance as Hitler envisioned, and it set the stage for what would soon happen south of Caen.

On Monday, June 12, 1944, several high-ranking U.S. military leaders landed at the Ruquet Valley from a DUKW for a brief inspection tour of the Omaha Beach area. Here, Adm. Alan G. Kirk (closest to the camera) is letting himself down from the side of the DUKW with U.S. Army Chief of Staff George Marshall right behind him. General Eisenhower has just planted his left foot on the PSP used to provide a stable surface for vehicular traffic driving up Exit E-1. Looking down on General Eisenhower, General Arnold leans over the gunwale of the DUKW. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190238

Le Dénouement

In the aftermath of the failure of the German Mortain counteroffensive, Patton’s Third Army made rapid advances to the south and southeast. General Bernard Law Montgomery’s 21st Army Group then struck southeastward from Caen in two back-to-back operations: Totalize and Tractable. The advancing Western Allies thereafter encircled the German Seventh and Fifth Panzer Armies during the second week of August in a pocket between the cities of Chambois and Falaise. By the evening of August 21, the pocket was closed with around fifty thousand German troops trapped inside. Although a significant number managed to escape, German losses were huge, and the Allies had achieved a decisive victory that resulted in the destruction of the bulk of German forces west of the Seine River, opening the way to Paris and bringing Operation Overlord to an end.

Captured in the battle of Saint-Lô, German Army and Luftwaffe prisoners are gathered on Utah Beach for transfer to England for internment. The group includes Poles, Austrians, and Czechs in addition to ethnic Germans. LST-21, a Coast Guard–manned landing ship, is waiting in the background to take them aboard, and a VLA antiaircraft barrage balloon floats above. U.S. Coast Guard Collection in the U.S. National Archives 26-G-0710441

A column of lucky German prisoners of war being marched out to a waiting LST across the sands of Utah Beach at low tide. They will be returned to England for internment and will, therefore, survive the violence and brutality of the end of the war in Europe.

The generals and the admirals departing Exit E-1 at the Ruquet Valley on June 12 on the DUKW that brought them ashore earlier in the day. The Widerstandsnest 65 bunker is behind them to the left. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190157

German prisoners carry a wounded man on a stretcher toward the water’s edge at Exit E-1 on Omaha Beach while a GMC CCKW 2.5-ton Truck drives past. These prisoners are moving out to a landing ship that will carry them to England for internment for the duration of the war. A DUKW sits on the sand at the upper right with men from the 1st Infantry Division gathered in a group behind it. U.S. Navy photograph, now in the collections of the U.S. National Archives 80-G-252570

Medics from the 2nd Naval Beach Battalion and the 261st Medical Battalion, 1st Engineer Special Brigade assist a paratrooper who has been wounded in the right arm as he steps onto the ramp of an LCVP that has pulled up to Utah Beach at high tide. The most seriously wounded troops were evacuated off the beach by landing craft so they could be returned to a hospital in England for critical treatment. Note that the wounded paratrooper is carrying a carton of Chesterfield cigarettes. U.S. Navy photograph, now in the collections of the U.S. National Archives 80-G-252629

The paratrooper from the previous photograph is seen here leaning against the portside gunwale of the same LCVP as it motors out to the fleet with five other wounded soldiers on stretchers lying on the deck. It is possible to tell that three of the men on the stretchers are paratroopers because M1942 Jump Jackets and a pair of jump boots are clearly visible. The stretcher patient with his feet closest to the boat’s ramp has a German helmet lying on his chest—an obvious souvenir from his experience fighting in Normandy. The LCVP’s two deckhands stand by the ramp. U.S. Navy photograph, now in the collections of the U.S. National Archives 80-G-252446

Taken just off of Utah Beach on June 8, this photograph shows an LCVP carrying a group of glider pilots out to the fleet so they can be returned to England. The most noticeable items identifying these men as glider aircrew are the USAAF wings on the left collars of two of the men’s shirts. Several noteworthy pieces of equipment can be seen in this photograph including M1 Helmets camouflaged with canvas scrim, M1936 Cartridge Belts, M1936 Suspenders, M1928 Haversacks, and at least one M1936 Musette Bag. Of particular interest are the two souvenir weapons leaning against the LCVP’s starboard gunwale just behind the pulley mechanism for the bow ramp: one is a German Kar98k Mauser carbine, and the other is a Soviet SVT-40 Tokarev semiautomatic rifle.

This photograph, taken on June 16, 1944, looks down the length of one of the “whale” causeways of Mulberry A, the temporary harbor built in the American sector at Omaha Beach. An M8 Greyhound Light Armored Car has just executed a left turn onto the causeway, and ahead of it are three M3 Half-tracks towing M5 3-inch Antitank Guns. A sign on the right side of the causeway reads: “Load Limit 25 Ton.” To the right, a GMC AFKWX-353 2.5-ton Cargo Truck waits to merge into the flow of traffic going ashore. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-195879

An M3 Half-track from the 612th Tank Destroyer Battalion (Towed) moves down one of the whale floating piers of Mulberry A just off of Omaha Beach on June 16, 1944. In the background, the jack-up legs of two Löbnitz pierheads can be seen as well as the open bow doors of an unloading LST. To the right, five U.S. Army small tugs are moored alongside one another. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-195881

Vehicles of A Company, 612th Tank Destroyer Battalion (Towed), 2nd Infantry Division come ashore on Omaha Beach at 5:15 p.m. on June 16, 1944, using one of the whale floating piers of Mulberry A at Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer. The lead M3 Half-track is towing an M5 3-inch Antitank Gun across a section of SMT as it drives onto the beach. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-195880

The storm that struck the Baie de la Seine starting on June 19 wreaked havoc on Mulberry Harbor A at Omaha Beach. Here, a Higgins LCS has been pushed up onto one of the whale floating piers, which has been buckled and bent by the pounding surf. Three damaged Löbnitz pierheads can be seen in the background. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps

Landing craft pushed up on the shingle of the Dog Red sector of Omaha Beach by the storm on June 21, 1944. LCI(L)-92, which was lost on D-Day, is on the left, with LCT-199 alongside. Beyond them is LST-543. The British LCT-2337 is on the right. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-193919

Three LCVPs from the Elizabeth C. Stanton–class transport USS Anne Arundel (AP-76) washed up on Omaha Beach during the storm on June 20, 1944. Debris and bodies are strewn on the shingle, and an LCT founders in the background on the left.

African-American soldiers from the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion hunt a German sniper at a farmhouse in Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer on June 10, 1944. They are being led by a white officer from Breaux Bridge, Louisiana, named Capt. Samuel S. Broussard, seen here with the vertical white stripe on the back of his M1 helmet and the M1911A1 .45-caliber pistol in his right hand. The man at the far left is armed with an M1 Carbine, while the man just to the right of Captain Broussard is armed with an M1903A3 rifle. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190120

The same group of African-American soldiers is seen here joined by five white soldiers during the hunt for a German sniper in Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer on June 10. Captain Broussard, with M1911A1 Pistol in hand, is coming down a ladder after searching the barn’s hayloft. Next to the barn is parked a camouflaged German Army–issue Heeresfahrzeug 6/Feldwagen 43 horse-drawn cart. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-332023

Three U.S. Army paratroopers lay dead in a roadside ditch just outside Sainte-Marie-du-Mont on June 7. The man closest to the camera wears the stenciled stripes of a corporal, and it appears that someone has rifled through his pockets, since the contents are scattered on the ground near him. A box of army K rations sits next to his head. Behind the two gas cans, the body of a third soldier has been covered by a GI raincoat, and the fingers of his left hand are visible. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190292

A light-machine-gun section of a weapons platoon from the 1st Battalion, 22nd Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division moves down a sunken lane near Marmion Farm just south of Ravenoville on June 6. The first soldier carries the thirty-three-pound M1919A4 Machine Gun with traverse and elevation mechanism attached to it, and the assistant gunner behind him carries the weapon’s M2 Tripod, along with a belt of .30-caliber ammunition. They are passing a German Army–issue Heeresfahrzeug 6/Feldwagen 43 horse-drawn cart as well as two 101st Airborne Division paratroopers. This image is actually a still taken from motion-picture film footage shot by T-4 Weiner of the 165th Signal Photographic Company, the Signal Corps photographer who jumped with the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment on D-Day. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-189928

This photograph shows an Ordnance Maintenance and Repair Company at work in a hedgerow-enclosed Norman field on July 18, 1944. One of the U.S. Army’s most important types of supporting units, these companies kept the guns running through the intense demands of combat. Among the more striking features of this image are the 116 M1919A4 Machine Guns lined up for servicing and the virtual mountains of M1903 Rifles piled up in front of the camouflage net in the background. Crates of spare M1919A4 barrels and traverse/elevation mechanisms sit close at hand, and, to the right, piles of M2 and M1917A1 Tripods await servicing. The two seated soldiers on the left are cleaning M1 Garand rifles, and the man to the right with his leg up on a crate is doing the same. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-191744

These two soldiers have taken up a position in a typical Norman hedgerow and are armed with two of the army’s oldest and newest infantry weapons: the M1917A1 .30-caliber water-cooled Heavy Machine Gun and the M3 .45-caliber Submachine Gun, also known as the “Grease Gun” by the troops. The M1917A1 machine gun had been in the service of the U.S. military for over a quarter of a century by the time it fought in Normandy during the summer of 1944. The Grease Gun, on the other hand, was used in combat for the very first time on D-Day. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-191283

These German Army soldiers from Kampfgruppe Heinz of Grenadier Regiment 984, 275 Infanterie Division were killed in action by U.S. soldiers of the 117th Infantry Regiment, 30th Infantry Division near Saint-Fromond just north of Saint-Lô on July 8, 1944. The presence of a spare barrel carrier and a belt of 7.92x57mm cartridges indicates these men were clearly a machine gun team. GIs have obviously searched the bodies thoroughly because their bread bags and gas mask canisters are open, and cigarettes are strewn on the ground around them. Also, their weapons have been removed. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-191087

Just 8.5 miles southwest of Bayeux and 1,500 feet east of the town of Littry, a Panzerkampfwagen 35R(f) from 3 Kompanie, Schnelle Abteilung 517 sits knocked out in front of a roadside oratoire (religious edifice) at the intersection of La Boissellerie and Avenue de la Chasse (present-day D189) on June 20, 1944. This type of vehicle combined the chassis of a captured French Renault R-35 light tank with a Czech-made 4.7cm antitank gun to create a hard-hitting, self-propelled tank destroyer. Schnelle Abteilung 517 was assigned to Grenadier Regiment 916 at noon on D-Day and quickly deployed to the area between Trévières and Bayeux, where it soon came into contact with fighting forces of the U.S. Army’s V Corps. The soldier crouching down in front of the Panzerkampfwagen 35R(f) has an M1903 bolt-action rifle slung on his back. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps

A captain from the 307th Airborne Medical Company, 82nd Airborne Division offers a wounded German prisoner a cigarette at the company’s medical aid station at La Ferme de la Couture exactly one mile west of Sainte-Mère-Église. Note that he is wearing a Geneva Convention medical brassard on his left arm below his 82nd Airborne Division shoulder patch, as well as a medical roundel painted on the side of his M2 Parachutist’s Helmet. The paratrooper at the far left is wearing the right-shoulder U.S. flag unique to the 82nd Airborne during Operation Neptune/Overlord, and an M3 Trench/Fighting Knife in an M8 Scabbard is strapped to his right shin. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190289

Two medics from the 90th Infantry Division administer blood plasma to a wounded German Army gefreiter (corporal) at a field hospital near Sainte-Mère-Église. The young corporal’s erkennungsmarken (identification disc) can be seen lying on the placket of his tunic. The medic on the right is wearing a Geneva Convention medical brassard, which covers the rank stripes on the left sleeve of his M1937 Olive-Drab Flannel Shirt, and a U.S. Army Medical Corps caduceus is pinned to the flap of his left breast pocket. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190593

Second Lieutenant Margaret B. Stanfill is seen here on June 14, 1944, preparing dressings in a tent at the 128th Army Evacuation Hospital at Boutteville, three miles southeast of Sainte-Mère-Église. A veteran of the landings in Algeria in 1942, she was the first nurse to wade ashore when the 128th landed on Utah Beach on the afternoon of June 10 after crossing the English Channel on the Liberty ship William N. Pendleton. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190305

A view of the hospital ward of the 42nd Field Hospital near Utah Beach in early June 1944 shows litter bearers, medical orderlies, and casualties. The second man with the helmet marking is clearly a medic from the 261st Medical Battalion, 1st Engineer Special Brigade, which landed at Utah Beach. Note some German Army prisoners/patients in the foreground. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190464

Medics load wounded Americans aboard C-47 number 42-24195 of 313th Air Transport Squadron, 31st Air Transport Group, Ninth Air Force at Advanced Landing Ground A-21 in Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer, just west of the Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach. The first medical transport from A-21 took place on June 9 at 6 p.m. A field hospital comprising members of the 806th Medical Air Evacuation Squadron was established near the airfield, which facilitated air transport of the wounded, including Norman civilians, to England. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190235

This grenadier from 17 SS Panzer Grenadier Division “Götz von Berlichingen” was killed near the town of Quibou six miles southwest of Saint-Lô when the 2nd Armored Division and the 8th Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division pushed through the area in late July 1944. He was an assistant gunner on a machine gun team, which is why a spare barrel carrier and a belt of 7.92x57mm cartridges are with his body. He wears M42 ankle boots and leggings (schnürschuhe und gamaschen), the “44-dot” camouflaged tunic and trousers unique to the Waffen-SS, and an M40 steel helmet (stahlhelm). National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-191302

A U.S. M7A1 105mm Howitzer Motor Carriage of the 14th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, 2nd Armored Division about to cross the train tracks on the Rue Holgate in the city of Carentan in late June 1944. Nicknamed the “Priest” because of the pulpit-like tank commander’s cupola on the right side of the vehicle, the M7A1 provided U.S. Army Ground Forces with a versatile and accurate self-propelled howitzer. National Archives and Records Administration/US Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190413

An M1 155mm howitzer from the 34th Field Artillery Battalion, 9th Infantry Division is towed on the N-13 by an International Harvester M5 (13t) High-Speed Tractor. The M5 was standardized in October 1942 from the T21, a vehicle based on the tracks and suspension of the Stuart light tank. International Harvester started production of the vehicle in 1942. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190385

A group of U.S. Army soldiers from the 313th Infantry Regiment, 79th Infantry Division fraternizing with a Norman woman in Cherbourg on June 26, 1944. The soldier at the far right is leaning on his M1903A4 sniper rifle. This photograph was taken by Pvt. Louis Weintraub of the 165th Signal Photographic Company. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-191153

Soldiers of the 79th Infantry Division march a column of German prisoners south along Avenue de Paris/Voie de la Liberté (N2013) at the point where it intersects with Rue Louis Lansonneur (D900) on the southern outskirts of Cherbourg on June 28, 1944. Although pockets of German resistance would hold out for a few more days, the organized defense of the city had reached an end. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190810

Staff Sergeant Jack Scarborough of Bossier City, Louisiana, examines the body of a dead German corporal among the fighting positions at Fort du Roule in the defenses of Cherbourg on June 26, 1944. An NCO in the 314th Infantry Regiment, 79th Infantry Division, Staff Sergeant Scarborough is wearing the M42 HBT fatigue uniform and is armed with an M1 Carbine. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps

A soldier from the 8th Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division enjoys a drink of Norman cider in Sainte-Mère-Église on June 11, 1944. This image is actually a still taken from motion-picture film footage shot by Sergeant Shelton from Detachment G of the 165th Signal Photographic Company. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190325

The village of Rocquancourt (at the left) is all but lost under a deluge of high explosive as the U.S. Eighth Air Force provides support for ground forces in the area south of the city of Caen. A total of 570 B-24 Liberator heavy bombers from the U.S. Eighth Air Force flew during the initial phase of Operation Goodwood from 6:30 to 8:15 a.m. on July 18, 1944. They struck frontline targets including German troop concentrations, transport targets, and command and control locations in the areas of Soliers, Troarn, Frénouville, the Mézidon railroad marshaling yard, Hubert-Folie, and Fontenay-le-Marmion (at the center bottom). National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps

The troopers of B Company, 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division pose for a group photograph near Utah Beach on July 11, 1944, shortly before the regiment would return to England. B Company, 507th suffered eighty-four casualties during its thirty-five days of combat in Normandy, cutting the company’s strength in half. Courtesy of George H. Leidenheimer

The bodies of three fallschirmjäger (paratroopers) are piled in the back of a truck at the Blosville Provisional/Temporary Cemetery two miles south of Sainte-Mère-Église. They are about to be buried by French civilians assisting the U.S. Army’s Graves Registration Service with the corpses of German war dead. The man at the left with the eye wound wears the collar insignia of flieger (private) and the man at the upper right wears the collar insignia of hauptmann (captain). These men served in Fallschirmjäger Regiment 6 until their deaths in the intense fighting north of Carentan during the first week of the invasion. This regiment lost just three captains during the initial phase of combat in Normandy. The officer seen here, therefore, is probably Hauptmann Emil Preikschat, who was the battalion commander of 1, Fallschirmjäger Regiment 6 when he was reported missing in action on June 8 somewhere near Sainte-Marie-du-Mont. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-190600

This photograph shows what was probably the most famous dump for captured weapons in Normandy. In a field one mile south of Isigny-sur-Mer on the north side of D5 between Hameau de la Madeleine and Ferme de la Petite Fontain, the U.S. Army established a collecting point that was ultimately packed full of vehicles and heavy weapons captured on the field of battle from 2 SS, 17 SS, 352 Infanterie Division, and other German units that fought in Normandy. This view shows the section of the dump where antiaircraft guns, antitank guns, artillery, and tires have been deposited. Easily identifiable here are such pieces of ordnance as the 2cm Fliegerabwehrkanone 30, the 2cm leichte Fliegerabwehrkanone 38, the 8.8cm Fliegerabwehrkanone, the 7.5cm Panzerabwehrkanone 40, the 10.5cm leichte FeldHaubitze 18, and the 15cm schwere Feldhaubitze 18. There is even an 8.8cm Raketenwerfer 43 rocket launcher at the far right. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps

Here is another view of the dump near Isigny-sur-Mer, this one showing the section of the field where armored vehicles were parked. Easily recognizable in this view are at least eight Panzerkampfwagen IV Ausführung H medium tanks armed with the 7.5cm Panzerabwehrkanone 40/3 main gun, including the “898” (center right) of the 8 SS Panzer Regiment 2, 2 SS Panzer Division “Das Reich.” The “425” (front and center) is a Panzerkampfwagen V “Panther” from Panzer Regiment 6, Panzer Lehr Division and is coated with zimmerit to prevent the use of magnetic antitank mines. Just to the left of the “425” is a Sonderkraftfahrzeug 251 Ausführung D half-track with another one parked next to it. Also recognizable here is a 15cm Schweres infantry Geschütz 33/1 Selbstfahrlafette 38(t) Ausf K (Sonderkraftfahrzeug 138/1) self-propelled howitzer and a Panzerjäger 38(t) Ausführung M “Marder III” (Sonderkraftfahrzeug 138) tank destroyer. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps

Four female members of a Norman family stand by the gate of their farm to greet passing U.S. soldiers on June 7, 1944. This photograph was taken in the tiny hamlet of Le Guay just five hundred feet east of the road leading out to Pointe du Hoc, and the soldiers are marching on what is now known as D514 in the direction of Grandcamp-Maisy. The first two men wear the Winter Combat Jacket (also known as the “Tanker Jacket”) and carry the M1903 rifle.

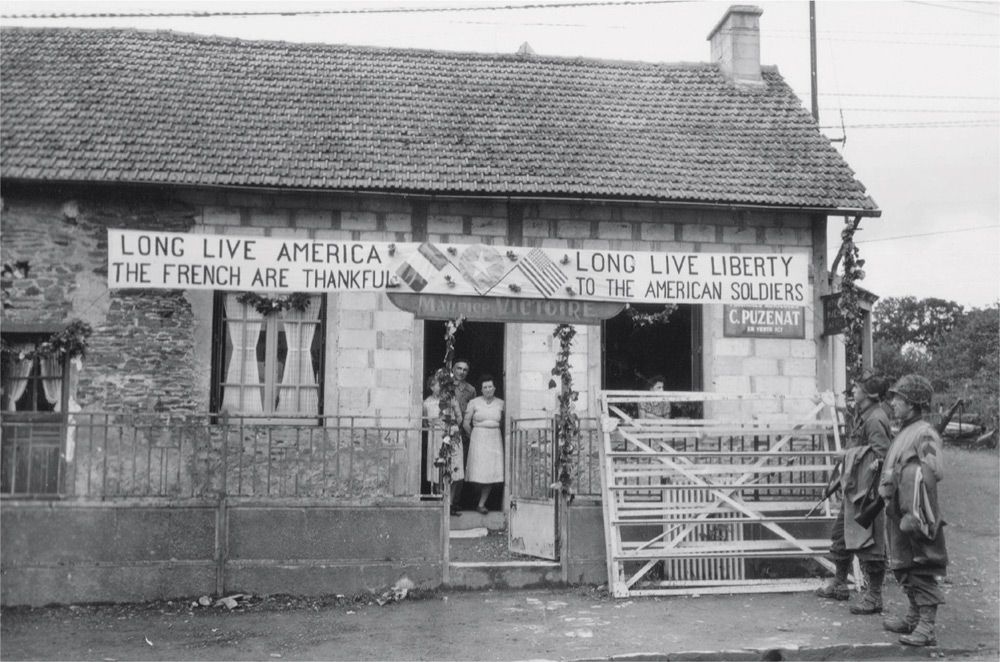

Two soldiers from the 2nd Armored Division pause to admire a banner decorating the façade of this electrician’s business at 45, Route de Balleroy in Le Molay-Littry 8.5 miles south of Omaha Beach. The Norman people abundantly offered expressions of gratitude like this during the summer of 1944. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-191171

On the road between Isigny-sur-Mer and Saint-Hilaire-Petiteville near Carentan, Adjutor Lecanu and his wife, Marie, lay a bouquet of flowers on the body of an American soldier who died after hard fighting in the area between June 9 and 13. A local butcher and World War I veteran, Monsieur Lecanu wanted to express his respect for the man who fell in battle for his freedom. The soldier is an infantryman from the 41st Armored Infantry Regiment, 2nd Armored Division. The scene was not posed, although it was recorded by a number of photographers, one of whom was crudely erased (on the right) by the censor, but who is still visible if you look closely. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps

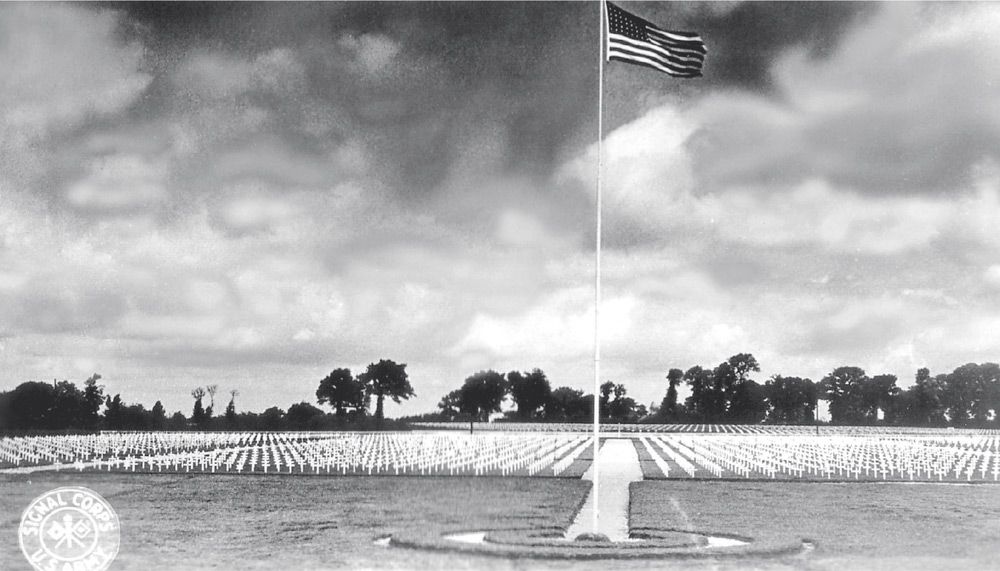

The temporary U.S. cemetery at Marigny is seen here shortly after it opened during the summer of 1944. Located one mile south of La Chapelleen-Juger and six miles west of Saint-Lô, it was the final burial place for 3,070 U.S. soldiers who lost their lives during the battle for Normandy, mostly during the vicious fighting of the Operation Cobra breakout. Just across the road from the burial area seen here, a cemetery for German war dead was established as well. The U.S. cemetery remained until 1948 when it was closed and the graves relocated to the new Brittany American Cemetery forty miles south near the town of Saint-James. The German cemetery at Marigny is still there with over 11,000 burials in it, mostly men from the Panzer Lehr Division. Today, a memorial marks the field at Marigny where the bodies of U.S. soldiers once lay in early graves. National Archives and Records Administration/U.S. Army Signal Corps 111-SC-276379