GAB Archives / Redferns

CHAPTER EIGHT

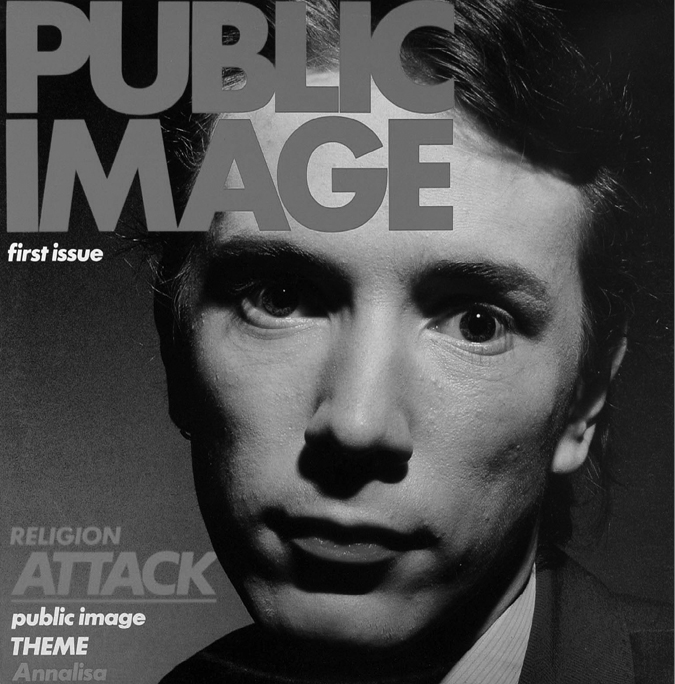

PUBLIC IMAGE

Punk’s Paradoxes of

Authenticity

London, October 1978

No gimmicks, no theatre, just us. Take it or leave it.

JOHN LYDON, onstage, early PiL gig

IT IS HARD NOW to remember the strong sense of anticipation and uncertainty with which Public Image Ltd. (PiL) were awaited. By late 1978, the conflicts and compromises of the first wave of punk were fairly evident. The original Sex Pistols had disintegrated and the intense excitement they had generated seemed to be dissipating. But John Lydon, formerly Johnny Rotten, was still a figure of intense fascination, and everyone wanted to know about his next musical move. Until then he had been seen only through the prism of the Sex Pistols. Now he was going to show the world who he really was—or so he said.

The period surrounding the release of his first post-Pistols single was somewhat overshadowed by the unpleasant news from New York where, on October 12, ex-Pistol Sid Vicious was arrested for the murder of his girlfriend Nancy Spungen. It was a few more months before Vicious died of an overdose, but he was clearly already on an inescapable downward spiral. As much as anything else, this emphasized that, in spite of ongoing activity and releases, the Sex Pistols really were finished.

Accounts of what had “gone wrong” with punk varied according to the teller—Malcolm McLaren and John Lydon each blamed the other for the Sex Pistols’ demise. Politically aware members of the punk movement, including the Clash, were trying to move on from the Pistols’ original disengaged nihilism by molding it into a more righteous anger through the Rock Against Racism organization. The artistic, fashion-oriented end of the movement (for instance the clique that centered on the King’s Road boutique SEX, run by McLaren and his then-girlfriend Vivienne Westwood) felt that as punk had spread beyond the original elite it had been coarsened and destroyed. Whichever of the various accounts you believed, the huge burst of energy created by the heyday of punk was still spreading in all sorts of ways and, as a prime mover, Lydon was bound to be watched closely.

The release of Public Image Ltd.’s debut single, “Public Image,” would finally give Lydon an opportunity to make a statement without interference. In the Sex Pistols, his nihilistic voice had been filtered through the showmanship of McLaren and interpreted in the light of Sid Vicious’s violence and the band’s destructive notoriety. The authorship of the lyrics of the Sex Pistols’ songs is still disputed. The most plausible account is that McLaren, Vivienne Westwood, and their associates fed some of their ideas to Lydon, who added his own viewpoint and transformed these suggestions into his own powerful words. But McLaren and Lydon ended up with different views of the meaning, direction, and purpose of the Sex Pistols, and this was the major schism on which the original band fell apart. Lydon had given an eloquent account of his own views in interviews, often stressing that the most important thing to him now was keeping his self-respect—“It’s all about being yourself,” he wrote later in his book No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs. But saying this is easier than putting it into practice: now his music would have to live up to his rhetoric.

THIS WASN’T, however, the only problem that Lydon faced. It was widely believed that punk’s message was one of being authentic, of cutting through the bollocks and simply telling it how you saw it. But the reality was far more confused. Punk was riddled with a series of paradoxes: it hymned authenticity but relied heavily on simulation in its performance; it aspired to success on its own terms but glamorized failure; its do-it-yourself aspect raised the issue of how to take and keep control in a genre that glorified the individual against the corporate machine; and it presented itself both as a simple negation and as something far more knowing.

In the last verse of “EMI,” Rotten affected a moronic monotone that transmogrified over a few lines into the derisive lines of the final chorus and the knowing pay-off (“Hallo EMI, goodbye A&M”). Within a few seconds he had gone from dumb aggression to cutting sarcasm. This moment epitomizes the combination that bewildered and panicked the music business. Music journalist Caroline Coon has contrasted Rotten with Mick Jagger, pointing out that Jagger faked a working-class accent to gain credibility, but that “his view of what it was to be working-class was that you should be thick and stupid, yet another conceit about the English class system.” Rotten was genuinely working class, and his parody of a stupid voice came as part of a package where he was clearly smart and confident—his dumb insolence was far more threatening to the establishment.

Earlier in the same song, he challenged “and you thought that we were faking?” as if even he wasn’t entirely sure. Because it still was unclear if punk’s real message was one of annihilation or a more constructive blend of free expression and mocking antagonism. Was this satire, insurgency, or a mixture of the two? And had the Pistols’ chaotic progress through three record companies been a series of absurd accidents or the result of a master plan? By 1978, no one had any clear idea of how to solve these paradoxes, and they were all obstacles that Lydon had to negotiate if he were to progress and survive.

Attitudes toward authenticity were from the start a deeply confused part of punk, as Lydon and McLaren certainly both knew. McLaren was influenced by a variety of artistic and political movements including Dadaism and anarchism, and he was especially interested in the situationists. This political movement had little direct influence on the punk musicians but fascinated the older generation of McLaren and his friends, especially those who regarded hippie idealism with suspicion. Situationism was essentially a strand of anarchism, which had commented on, and to some degree influenced, the Parisian uprising of 1968, at which McLaren would sometimes falsely claim to have been present. Echoing the ideas of situationist gurus Raoul Vaneigem and Guy Debord, which became more widely known in the years after 1968, he saw punk as essentially a posture, a consciously assumed style and pose that created friction and revealed the simulations in bourgeois society.

Vaneigem, in particular, had seen authentic artistic expression as the route to the revolutionary transformation of society. He once wrote: “In a gloomy bar where everyone is bored to death, a drunken young man breaks his glass, then picks up a bottle and smashes it against the wall. . . . Yet everyone there could have done exactly the same thing . . . a gesture of liberation, however weak and clumsy it may be, always bears an authentic communication.” This kind of rhetoric can be used to glorify rebellious gestures of any sort, no matter how irrelevant or risky. McLaren and Westwood were happy to play with such ideas and, in some instances, to instigate or encourage violence simply for the notoriety and publicity it brought. But for them punk’s violence could always be seen as a game, or even as a piece of social experimentation they were carrying out on a younger group of people. At the Nashville club in London in April 1976, Westwood deliberately started a fight because she thought the Pistols’ set was boring. Subsequently the Vaneigem quote above had an uncomfortable mirror in reality at a “punk festival” at the 100 Club in September of that year. Following the Sex Pistols’ performance the previous day, the Damned headlined the second night. Their set was disrupted when Sid Vicious, who hadn’t yet joined the Pistols but was already a fan, expressed his hostility to their set by throwing a beer glass at the stage. It smashed on a pillar, and the resulting debris hurt several people, including a girl whose eye was supposedly cut by a shard of broken glass. The girl’s injury may in fact have been a journalist’s embellishment of the incident, but the danger was clear in any case.

It is easy to see Malcolm McLaren as the embodiment of inauthenticity in the story of punk, and his later accounts of the period certainly emphasized the mocking pretenses rather than anything more fundamental. Musicologist Greg Wahl, for instance, has said that McLaren’s “role in the ‘creation’ of punk as inherently artificial probably cannot be overestimated.” But to McLaren, the music was subsidiary to a kind of political direct action, a form of self-expression for which the music and style was no more than a convenient conduit. Like so many vanguardists, including the situationists themselves, he felt let down by the masses who failed to enact his vision in the exact way he wanted them to. His ideal of a politically focused movement undermining conventional society, in a direct inverse of the sixties hippies he had despised, never materialized. As the punk scene started to expand and get out of control, he became emotionally detached from it and from the band. He started to feel that the music had never been the point, and tried to move into film and other projects to carry on the momentum. This was one of the reasons that he drifted apart from Lydon, who was still on the front line of the chaos that had been created.

The violence surrounding the group inevitably snowballed as they became more notorious. When John Lydon was attacked and stabbed by a group of youths who were hostile to punk following the release of “God Save the Queen,” he saw one side of the violence that was increasingly being let loose. He was in an exposed position, out on the streets of London, where this game was for real. In any case, he rejected McLaren’s belief that the members of the Sex Pistols were simply pawns in a political game. For Lydon the band was an opportunity to express a genuine, deeply held disgust with society. He felt that he had the ability to occasionally hit the nail on the head in putting across the feelings of alienation and boredom of many youths. Nonetheless, he understood that in doing so he was to some degree playing a part—the character of Johnny Rotten was a cathartic, extreme version of his personality from whom he could take a step backward when it became necessary. As Rotten, he hated traditional rock’n’roll and wanted nothing more than to destroy it. As Lydon, he liked all sorts of music—for a Capital Radio show in the summer of 1977 he chose records as widely varied as Captain Beefheart, Peter Hamill, and Neil Young, displaying a more complex side of his personality than he generally chose to reveal at that stage. It was an interview that infuriated McLaren for two reasons: it revealed Rotten to be more than the cartoon demon that suited McLaren’s purposes and it was also a sign that McLaren could no longer control the star that he liked to regard as his creation.

So Lydon did not entirely identify himself with Rotten—he could take a step away from the “filth and the fury” when he needed to, as could many of his contemporaries. Ray Burns, Marion Eliot, and Susan Ballion, ordinary youths from London’s suburbs, suddenly became Captain Sensible, Poly Styrene, and Siouxsie Sioux. The masks adopted by performers such as these allowed them to behave outrageously and to express themselves in ways that they couldn’t otherwise have done. Different performers used punk as a vehicle to convey their own distinct styles and ideas. The Damned were frequently hilarious, X-Ray Spex skewered the absurdities of the disposable society, while the Banshees moved quickly from punk toward their own brand of gothic cacophony. For these and many others, extreme personas and stage names allowed a spectrum of self-expression that ranged far beyond the Pistols’ nihilism. One of the most exhilarating aspects of punk was that feeling of complete liberation from yesterday’s normality.

But for some of the youths who took up the punk ideas in this early period, the irony—the distance between persona and real person—was lost. For them the only way to become a true punk was to take on the full identity and costume and to become as reviled as possible. While swastikas or rapist hoods might have first been worn in an ironic or challenging way, others simply mimicked this style in a way that could be seen as offensive and dangerous. There were elements of actual fascism creeping in at the fringes of the poorly defined politics of the movement. Riots at Sham 69 concerts and elsewhere were providing an ugly counterpoint to the music, and the far-right National Front was increasingly interested in hijacking part of the energy and disruption that punk created. While much of the initial violence had been more simulated than real, it became increasingly hard to get the released demons back into their caves.

SID VICIOUS was the prime example of the kind of punk rocker who forgot, or never realized, that the punk attitude could be simulated and ironic. He took it to an extreme, making the idealization of spitting, hatred, bloodletting, and violence into a manifesto for life, leaving behind a large part of his genuine sense of humor on the way. The definition of the hardcore or authentic punk was being drawn either along the lines of who had been there first or who was prepared to be the most extreme in re-creating the original postures. In both respects Sid excelled. He had been one of the crowd of youths hanging around McLaren and Westwood’s shop, and a close friend of John Lydon’s from their teenage years in North and East London. Once Lydon became Rotten, Sid played in other transient punk bands and became the Pistols’ überfan, being involved in several of the moments of violence that helped establish their notoriety.

One interesting aspect of punk’s attitude to authenticity is the way it involved simulation. When someone’s persona is as close as possible to the individual’s actual personality, the persona is commonly seen as real, or authentic. In this way, Will Rogers or Woody Guthrie had been early exemplars of authenticity—what you saw was pretty much what there was. By contrast a very theatrical performer who adopted mannerisms to project a persona would be seen as relatively fake.

But punk actually turned this calculation on its head. Most of its protagonists adopted self-evident personas, indicated by their assumed names and absurd behavior. Paradoxically, this pretense allowed the performer a liberating degree of honesty: singing about a teenager’s life of boredom and masturbation was easier to do through the guise of a fictional alter ego. Many punk performers used their masks as a fundamental way of channeling their self-expression.

However, since it was still seen as fake to be a different person from your persona, authenticity for the punks often became defined by how well you could turn yourself into your persona. John Beverly (or Simon Ritchie as he was sometimes called) had been a relatively polite, withdrawn teenager, a fashion victim who idolized David Bowie and Roxy Music. But once he entered the punk circle and became Sid Vicious, it was incumbent on him to turn himself into a real-life golem of derision and aggression. A lot of his persona was undoubtedly an exaggeration of parts of his real personality, but in order to be the hardcore punk he wanted to be, he eliminated all other aspects of his identity. In his autobiography, Lydon commented that Vicious “tried his very best to out-Rotten Rotten, but he didn’t understand Rotten was my alter ego. He would think that made me a fake.” The real John Beverly was still there, but it was rare that anyone was allowed to catch a glimpse.

When Sid finally joined the Pistols, after Glen Matlock’s departure in early 1977, he found himself in a band under siege. They played rarely, and every gig was subject to uncertainty and confusion. But when he got the chance to perform or appear in public, Sid took his chance eagerly and played out his fantasies of the uncontrollable rock star to the fullest extent. By doing this he quickly became emblematic of the band, in spite of his lack of musical competence or input. His personal life started to get out of control as he and girlfriend Nancy became more heavily involved with heroin. By the time the Pistols reached America for their first, and ultimately final, tour, his behavior was so erratic that Rotten, his oldest friend in the Pistols clique, was barely speaking to him. Unable to comprehend how jaded his bandmates were, Sid complained that he was the only one who really entered into the Pistols’ spirit on that tour. In San Antonio he used his bass to club a stage invader over the head. In Dallas he was headbutted and bled heavily over his instrument. “Look at that—a living circus,” was Rotten’s acid comment onstage. At one point Sid made his oft-repeated boast—that he would die a rock’n’roll death—to photographer Roberta Bayley, saying that he wanted to die before he was thirty, “like Iggy Pop.” Bayley broke the news that Iggy was still alive, but even that didn’t seem to dent his romantic aspirations. Not only was Sid living out other people’s fantasies, he was even following in imaginary footsteps.

At the final show at San Francisco’s Winterland, Sid pulled rock’n’roll poses with abandon while Rotten’s contorted body language revealed his withdrawal and disdain. Rotten’s famed parting words—“Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?”—referred to himself as much as to the audience that night, and to the punks in general. He had had enough of the circus and wanted out.

McLaren had high hopes that Vicious might replace Rotten as the face of the Pistols, but by this stage Sid hated McLaren almost as much as John did. Nonetheless McLaren managed to persuade Sid to participate in the later recording sessions and the filming of The Great Rock and Roll Swindle. This led to one of Sid’s defining moments, the film’s absurd parody of “My Way.”

A CHAOTIC MIXTURE of fact and fiction, The Great Rock and Roll Swindle was partly a vehicle for McLaren to give his own version of the Sex Pistols’ story (with himself as antihero and prime mover) and partly a piece of conscious mythologizing. Jean Fernandez of Barclay Records, the band’s French record company, suggested “My Way” for Sid, initially because his company owned the publishing rights to the song—yet the idea stuck, and the filming was arranged in an empty Parisian theater. Sid had been reluctant to make the journey to France, but in the end he was coaxed into giving an entertaining performance. Dressed in a trashed dinner suit, he part crooned, part brutalized his way through the song and, as the final touch, enthusiastically opened fire with a fake gun on his audience. The song was released as a double A-side, with the preposterous “A Punk Prayer” on the reverse, and was one of the best-selling Pistols singles, comfortably outselling “God Save the Queen.”

Earlier, after the glass-throwing incident at the 100 Club, Sid had spent a few weeks locked up in Ashford Remand Centre. While he was there he wrote a letter in which he mentioned that Vivienne Westwood had lent him a book about Charles Manson, and that “one of the things I believe in since being slung in here is total personal freedom.” The problem with half-baked ideas of anarchism is that the idea of freedom tends to become detached from more arduous concepts of how to live responsibly in a society without rules. By contrast, the anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon once wrote that “it is our right to maintain our freedom. It is our duty to respect that of others.” Vicious, in his eagerness to please and be accepted as a real punk, had aspired to an ideal of irresponsible freedom. He felt genuine pride in his notoriety. But for a young junkie to boast, even in parody, of doing it “My Way” was a bathetic reflection on his eventual self-destruction.

His use of the song also tangentially illustrates some of the ways that the cult of personal authenticity had affected music over the previous decade. The original, “Comme d’Habitude” written by Claude François, was adapted, very loosely, by Paul Anka in 1967. In the postwar period there had been a much stronger tradition of songs adapted from foreign sources—“It’s Now or Never,” “Strangers in the Night,” “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me,” and “I Can’t Help Falling in Love with You” are all examples. This tradition, which had enriched and broadened popular music, was largely curtailed by the era of singer-songwriters.

“My Way” was a late flowering of this very different era of popular music. For all the inanities and simplicities of postwar pop, its songwriters did periodically manage to take on broader themes. One aspect of this was a fascinating tradition of songs that looked back over the narrator’s experiences from the end of life. It’s no surprise that the greatest of these songs were written by skilled songwriters capable of the emotional detachment needed to enter into a third-person state of mind, and were best executed by performers who were able to “act” out a song. Leiber and Stoller wrote “Is That All There Is?” an elegant survey of life’s disappointments, performed with cheerful abandon by Peggy Lee. Charles Aznavour’s “Yesterday When I Was Young” is equally elegant, but far more melancholy. In Randy Newman’s “Old Man,” the narrator dispassionately observes his dying father and comments that “everybody dies.” French songwriter Jacques Brel’s morbid and hilarious takes on mortality included “Le moribund” in which the dying narrator forgives his wife for her many infidelities and invites his friends to dance and sing with abandon as he is lowered into his grave.

(“Le moribund” was [mis]translated into English as “Seasons in the Sun,” and the song’s fortunes reflected the shift of perspective in pop music. With bland lyrics that removed the sharpest stings from Brel’s original, it was performed with modest success by the squeaky clean Kingston Trio in 1964. But ten years later, the personal had become inescapable, and Terry Jacks’s 1974 version became a massive hit on the back of mawkish publicity stressing that the song was recorded as a tribute to a recently deceased friend.)

Within this tradition, “My Way” represents a certain summit. Maybe it’s not a great song—it is a relatively mundane narrative, although it has an inescapable grandeur in its pacing and cadences. Frank Sinatra’s definitive version, recorded late in his career in 1969, precisely conveyed the feeling that here was a singer who had lived through the ups and downs that the song demands. Brash, boastful, yet reflective, his spirited performance made it into a classic, a ready-made cliché that anyone could join in with after a few drinks, a generation before the rise of karaoke. It was also an example of how songs could become identified with a singer who wasn’t a songwriter. People identified this song as Sinatra’s own, even though it was written neither by nor about him.

When Sid Vicious sang “My Way,” he was also near the end of his career, but he couldn’t know that yet. “My Way” was seen by those around him as a holy cow, an idol overdue for desecration. Sid’s version made a thorough job of disemboweling it. He swore, boasted of killing a cat, and twisted lines of the song so that they referred to drugs and apathy—“There were times, I’m sure you knew, when there was fuck fuck fuck else to do.”

It was a grimly effective comedy performance. In Vicious’s hands, the song became self-referential but empty. By this stage Sid was a junkie, pure and simple, and it’s unwise to read too much into his state of mind when he sang the song. And, of course, it was by no means a representative punk song—there were many punk moments that were more interesting or worthwhile. But it does serve as an example of the dead end that Sid’s version of punk had driven into. This was a private joust against conformity and normality—what else could it be for a twenty-one-year-old with no real knowledge of life outside the strange world he inhabited?

THE IMPULSES BEHIND the wider punk movement had been varied—there was in the mid-seventies a real feeling in Great Britain, the United States, and elsewhere that something new was needed. Seeing the blandness of pop and overblown verbiage of rock, the young bands that would end up as punk were looking for their own kind of music, one that really meant something to them. But for many, meaning had become identified with personal, solipsistic issues, darkness and negativity, while honesty was often signified by brutal simplicity and lack of musical skill. Punk may have declared a year zero, but it was nonetheless drawing on a wide variety of antecedents that ranged from the Velvet Underground and the Stooges to the garage bands of the sixties. Iggy Pop had started out as a blues drummer but with the Stooges had consciously set out to create music for “suburban white trash.” John Lydon was one of many in his generation of London musicians who saw Iggy, post-Stooges, playing a seminal gig at the Scala in Kings Cross, a dilapidated cinema that doubled as a seedy but memorable concert venue. When the punks tried to re-create music, they were at first drawing almost entirely on white rock antecedents, and they took the quest for personal authenticity, as it was expressed in rock music, largely for granted.

In the United States, the initial wave of what would become known as punk or new wave was extremely varied. Patti Smith used stripped-down instrumentation as backing for her poetic visions on a wide range of subjects. Pere Ubu created a manic collage of disturbing art noise and absurd ideas. Television used guitars in a rigorous, direct way that negated rock’s overblown tendencies while creating new directions for the guitar band. Talking Heads took this further, using guitars in a rhythmic chatter to underpin David Byrne’s dislocated lyrics. Richard Hell introduced the subject matters of nihilism and sexual dysfunction that would become commonplace as punk developed.

But it was two other bands that most directly influenced the UK punk scene. The Ramones played rock songs with a minimum of musical complexity but the most extreme amphetamine speed possible. In their regulation leather, uniform dork haircuts, and adoption of the same last name, they were more cartoon than reality, and used their mixture of assumed idiocy and cunning to play around with controversial and brutal ideas, from “Blitzkrieg Bop” to “Beat on the Brat.” A large part of the London punk scene developed in complete isolation from the scene in New York, but the Ramones’ first album was one of the few American punk albums that was widely listened to in the UK in 1976–77. The New York Dolls were less well known in the UK and had less direct influence on the musicians, but their disinterred rock’n’roll style was the direct source for Malcolm McLaren’s search for confrontation, transgression and twisted glamour in a London band.

The influence of these two bands, filtered through the Sex Pistols, meant that English punk took only a restricted range of possible influences from across the Atlantic. Three-chord drones and breathless speed were favored over any sign of musical complexity. The poetic and doomed romantic influences of Rimbaud and Verlaine via Patti Smith and Television and the industrialized cutups of Pere Ubu had little impact. The first wave of British punk concentrated on two lyrical possibilities: a basic focus on the here and now (whether nihilistic in the case of the Pistols, or wryly humorous as with the Buzzcocks or Alternative TV) and the espousal of outrageous and controversial thoughts and ideas (“White Riot,” “Holidays in the Sun,” “Oh Bondage, Up Yours”). These options were preferably expressed in a voice that echoed the anger and incoherence of youth, rather than in any more sophisticated style.

This restriction partially fed back into the American punk scene, which absorbed some of the simplifications of the British equivalent. Black Flag, the Dead Kennedys, the Circle Jerks, Minor Threat, and other bands across the country showed the influence of British punk in their lyrical approach, aggression, and simplicity. Prior to this, most American punk bands could be identified as art-rock—even bands like the Ramones, the Dictators and the Stooges saw themselves this way. In this respect they were all following in the footsteps of the Velvet Underground. But now the complete contempt for “art” shown by the British punks started to be the dominant attitude in the American punk scene as well.

David Thomas of Pere Ubu has complained that the new- wave movement “wiped out a generation of musicians,” lamenting that the interesting bands of the period, such as Devo and Talking Heads, had developed in isolation. In his view, punk created a template for young musicians to aspire to, but one without substance, a straitjacket that limited their aspirations. “All these people suddenly had something to copy, and at that point, it doesn’t matter what you’re copying—you’re still copying.”

IN TRYING TO CREATE meaningful songs for adolescent minds, punk had the virtue of using simple ideas based in everyday life. In this respect, it was a refreshing and liberating influence. Belfast’s Undertones are just one example of a band that took punk’s limited style and applied it in a fresh way, focusing on teen concerns and everyday scenes to create basic music that was joyous and exciting. Many other bands of the period based their approach on punk’s ideals but found ways to take a step forward. But for John Lydon, it was hard to see a way out of punk. He had been defined by the negation and anger of the Pistols, and this severely restricted his options. The huge task facing him in his solo career was how to expand to something meaningful and worthwhile.

He had watched Sid’s decline and had experienced firsthand the problems created by punk’s cartoonish glorification of violence. He had observed with disdain McLaren’s attempts to depict himself as the antihero of punk, and his attempts to film the story of the Sex Pistols as nothing more than a giant situationist con. Now he had to decide how to react.

Having declared what he was against, what he regarded as being fake and worthless, in great detail, the specific question Lydon now had to answer was what he saw as being real and worthwhile. “Public Image” was his first statement of intent. He wanted to debunk the image he had created; he would refuse to be a star, refuse to play out the pantomime of punk, and go his own way. Using his real name (he had to do so because of McLaren’s claim to legal ownership of his alter ego, though he may have wanted to in any case), Lydon would be true to his real self, not to the idiotic expectations of the press or the punk faithful. To do this, he needed to redefine his public persona.

“Public Image” was stunning in its achievement of these limited aims. It blew away McLaren’s assertions that Rotten was a mere tool in his literary creation. Keith Levene’s chiming guitars cut remorselessly across Jah Wobble’s driving bassline as Lydon’s lyrics attacked the shallowness of those who saw nothing but surface image and ambiguously claimed his own public image as his own creation. In dismissing the fakery of McLaren, he set himself up by default as a genuine artist, one who simply spoke his mind and told the truth as he saw it.

There’s never been a voice that comes within spitting distance of Lydon’s for its intense, scabrous assault on the ears. Listening to his early recordings now, it’s no surprise that he frightened people. The first two lines of “Anarchy in the UK” with their threatening declamation and harsh dissonance still sound like the purest distillation of malevolent rage conceivable. In “Public Image,” from the sinister opening “Hello”s that descend into derisive laughter to the final howls, Lydon was at his magnetic, repulsive best. Musically the song went significantly beyond mere punk. Listening to it now, it seems to weirdly prefigure a lot of disparate later music from U2 to Radiohead to the Prodigy in its driving guitars, oblique rhythms, and concentrated fury. But at the time it was simply a fascinating, pure assertion of escape and individuality. It showed that Lydon was someone to be reckoned with, not a puppet who would fade away once the original band disintegrated.

The grim determination that drove Lydon to make this record should perhaps have been a warning to McLaren that he wouldn’t be easy to beat. More than a decade of legal battles over the Sex Pistols’ finances ensued; Lydon was the ultimate victor, together with band members Steve Jones and Paul Cook, who became late defectors to his cause, having initially supported McLaren’s case.

Public Image Ltd.’s second album, recorded in 1979, was a three-record 45-rpm limited edition packaged in a steel case and labeled Metal Box. Here the band tried to create a kind of antimusic, bringing in some of the reggae influence that had become a strong part of the punk scene. Lydon had visited Jamaica in 1978 with the DJ and filmmaker Don Letts, looking for bands to sign to Virgin Records. Virgin’s owner Richard Branson, unsure how to deal with the Sex Pistols’ break-up, had suggested the trip as an interim measure, knowing that Lydon had been interested in reggae since his youth in Finsbury Park. Metal Box was a clearer glimpse of Lydon’s intended direction, absorbing influences from dub (reggae’s stripped-down, remixed cousin) and from more dissonant sources—such as the krautrock of Can and the exuberant weirdness of Captain Beefheart—to create a twisted backdrop for Lydon’s disturbing vocals.

However, it is questionable whether even at this stage of his career, Lydon consistently achieved the degree of personal authenticity he tended to claim in his interviews. He always stressed that his targets were hypocrisy and fakery. But throughout his career, his actual lyrics showed the strain of trying to express himself without fakery, and in this respect there was a mismatch between his professed goals and the resulting music. He often wrote in poetic fragments that were hard to interpret. And rather than speaking directly about himself, he wrote about the sheer complexity of self-expression. Lines such as “There are no easy answers to elongated questions” (“Open and Revolving”) or “I can only feel and think in the language of cliches” (“God”) suggest a writer confronting the difficulty of making a genuine statement. Lydon certainly didn’t want to lie, but he couldn’t always find something true that he wanted to say.

The stand-out track of Metal Box, “Swan Lake” (also known as “Death Disco”), took on the intensely personal subject matter of the cancer suffered by Lydon’s mother. It is an oblique but emotionally affecting song. However, the refrain of “words cannot express” acknowledges the impossibility of truly recording the experience, even as Lydon confronts the pain and confusion caused by his mother’s death. It makes a fascinating counterpoint to Lennon’s “Mother” (discussed earlier). Lennon’s attempt at personal authenticity led him to a bald statement of his pain, whereas Lydon took a more nuanced and indirect path, partly reflecting his different personality. One could even argue that Lydon’s is the more honest approach because he clearly understands the impossibility of trying to communicate something so personal.

Over the years following this album, Lydon led his band through a variety of innovative and dislocated musical styles, always maintaining his derisive attitude toward image and fakes. His message remained somewhat blank and opaque at times, but to the surprise of many, he found a way forward from the staged outrage and aggression of punk while continuing to make a living in a business he had scorned. The band suffered from persistent financial, personal, and organizational problems, and their musical output was irregular. Guitarist Keith Levene departed after their third album, The Flowers of Romance; thereafter the band became little more than a backing group for Lydon, with no settled lineup. As a result, the later material was of very uneven quality and style. Yet no one should underestimate the difficulties Lydon faced, or his achievement in finding any kind of route out of the situation he was in after the Pistols’ breakup. His long-term musical career may not have been entirely satisfying, but for him to have survived and prospered at all under the circumstances is remarkable.

WHILE JOHN LYDON found his own way of dealing with its aftermath, the first wave of punk was still spreading slowly across the globe. The message that survived the transition of place and time was in many cases less cynical than Lydon’s worldview. The idea that anyone could start a band, given a few rudimentary instruments and the right attitude, was empowering and liberating for tens of thousands of adolescents. An unprecedented explosion of new music occurred (seeing punk as being only about the Kings Road in 1975–77, as some of the original British participants do, is a bit like saying you weren’t involved in the War of Independence if you weren’t at the Boston Tea Party). The London punk scene rose up and imploded over a very short time, as did parallel scenes in the United States. With punk and new wave on both sides of the Atlantic, early participants have tended to deride those who followed in their wake as imitators. But some of the most interesting consequences of the punk ideals developed only during subsequent years.

Punk had been based on a radical posture that hit a chord with youths because of their genuine feelings of alienation. At first it was defined mainly by opposition: to hippies, disco, the music business, the status quo—well, to almost everything. The Ramones succinctly parodied this negativity in “I’m Against It,” following a list of dislikes by singing “I don’t like anything.”

The Sex Pistols in particular had been a largely nihilistic force, with Johnny Rotten remembered for declaring “no future” and wanting to “destroy passers-by.” As he wrote in his book about the period: “Sometimes the absolute most positive thing you can be in a boring society is completely negative.” But punk was also about simple apathy and boredom that was transformed into energy when it was given a voice. The challenge for punk was how to use that energy and whether or not it could be transformed into anything more positive than early punk’s postures of boredom and anger. By 1978, the Clash and others were attempting to channel the spirit of punk into positive politics—at home through the antiracist movement and abroad by interacting with other musical cultures and political movements. The two-tone scene (a British-based ska revival) would subsequently take this baton by creating the first genuinely multicultural music scene England had seen. Meanwhile, bands like Crass and Chumbawumba fostered a more politically literate approach to music, combining agitprop with performance. In these ways, punk’s influence was very positive, as it demonstrated to a generation the power that such a basic and direct form of music could generate.

One strong impact the British scene had on American music came in the idea that anyone could start a band, and many bands developed the do-it-yourself, or DIY, philosophy into a way of life. The Replacements were a good example of the new “postpunk” bands. Starting up in Minneapolis in 1979 as a straightforward punk band, their songs were autobiographical in an adolescent but drily humorous way that avoided the petulance of the angrier bands of the era. In this way they were perhaps closer in spirit to the Buzzcocks than to the Sex Pistols. In songs like “I Hate Music,” they demonstrated their punk nihilism while simultaneously undercutting the message with sly comedy (“It’s got too many notes”).

As the band progressed, they embodied the transformation of punk from a music that was frequently negative into one that celebrated misfits and losers of all kinds. They also took the original punk influences—the garage bands, Iggy’s suburban slacker blues, and the less nihilistic New York punk of Television and Patti Smith—and reinterpreted them in a more down-to-earth way. From punk roots, they developed an ironic eclecticism in their music, taking them close to pop success in the mid-1980s with songs like “I Will Dare.” But their celebration of failure carried through into their major-label years, and they tended to deliberately sabotage themselves, performing drunk on TV and, in the early years of MTV, issuing a video for “Bastards of Young” that consisted of nothing but a static shot of a record being put on a turntable and then rotating through to the close of the song. The idea behind it, a refusal to conform to the rule that says you should perform for your audience, was strongly reminiscent of Public Image Ltd.’s first concerts, in which the band played their entire set behind an opaque curtain. It also embodied a rejection of fakery—rather than lip-synch, or pretend to perform in any way, the band put up a metaphorical blank wall. Seeing performance itself as a kind of fakery led Public Image to an ethic of antiperformance, which affected their approach to all aspects of their music.

The Replacements embodied the contradictions that were bequeathed to this generation of bands. Both attracted and repelled by success, they strongly wanted in their early years to avoid selling out. Their chaotic Saturday Night Live performances were exact mirrors of many of their drunken live shows (like the Sex Pistols, they swore on air), and to change their style just for the cameras would perhaps have felt untrue. But there is a big difference between the comic bonhomie of watching a chaotic live gig and seeing the same disarray through the cold light of television.

Having started out with a credible punk manifesto, the band’s refusenik attitude won them admirers but also handicapped them when it came to winning new fans beyond their original constituency. Singer Paul Westerberg was an important player in punk’s slow journey toward the grunge bands of the nineties, casting himself as the champion slacker, a role he found hard to cast aside. Prior to their 1987 album Pleased to Meet Me, the band threw out their most reckless member, guitarist Bob Stinson. The title and cover image (a handshake between a “suit” and a punk who were actually the same person) clearly flagged this album as a self-conscious “sellout.” And there was a noticeable move toward the mainstream in the greater ambition and musical complexity of the songs: for the first time, this sounded like a band that actually knew how to play their instruments. However, the quality of Westerberg’s songwriting was disguised by rough production, giving it a vibrant urgency but at the same time guaranteeing that it wouldn’t be too successful. Even as they were making a song and dance about how they were selling out, they couldn’t entirely bring themselves to let go of their roots and really go the whole hog. Commenting on one of the best tracks, music writer Stephen Thomas Erlewine said that “the fan love letter ‘Alex Chilton’ reveals more than necessary—even though Westerberg is shooting for stardom, he has more affinity for the self-styled loser, which means he never wants to make the full leap to the mainstream.”

The Replacements did have one more attempt at commercial success, the album Don’t Tell a Soul in 1989, for which they even made MTV-friendly videos. After ten years they were finally playing by standard music business rules, but by then their best chances of broader success were gone. The single “I’ll Be You” was a minor hit, but there was no major breakthrough. The album alienated many of their hardcore fans, who hated its highly produced sound, and the band subsequently disintegrated.

In the career of the Replacements, we see the problems caused by glorifying a lack of musical competence and the difficulty of turning a cult of failure into success. These troubles persisted in American underground music. They came closest to being solved by Nirvana, who actually managed to turn slackerdom into mainstream success but who nonetheless succumbed to the friction contained within this paradox.

In any case, the aversion to competence and success was largely an irrelevant fetishization. Punk’s do-it-yourself philosophy was partly expressed through a dislike of overproduction. Musical proficiency had certainly been overrated in the earlier part of the decade, leading to the musical excesses of progressive rock and to pompous absurdities such as Deep Purple’s Concerto for Rock Band and Orchestra. So for a while, the punks’ refusal to admire proficiency was refreshing. The raw sounds of unskilled players had long signified passion and meaning in some quarters. Punk was following in the footsteps of earlier artists such as Neil Young and the sixties garage bands, and even some country music, although it was perhaps the first time that an entire movement had taken this attitude as a commandment. And because some apparently meaningful music was created by musicians of limited skill, two non sequiturs came to be accepted as fact by the punks. First, anyone who was musically incompetent could create something more meaningful than a skillful musician. Second, and more unreasonably, it became an unwritten law that it was impossible to do anything meaningful in a more skilled way.

Of course, excessive slickness can be a dull trait in any kind of music—a degree of looseness or rawness carries passion, even with skilled performers. Punk’s search for energy mirrored attitudes among fans of other styles—including jazz and standard rock—who often preferred a “live,” spontaneous feel in music. One of the great things about punk was the vibrancy that resulted from this attitude.

However, do-it-yourself at this stage was recognized as such only if the rough edges were visible enough to imply that the music was being played incompetently. Bad playing became a signifier of DIY and therefore a guarantee of authenticity, which helps to explain the hostile reaction of many of the Replacements’ fans to their increasing level of skill and production. In the immediate postpunk period, those influenced by punk ideals tended to treat any sign of slickness with disdain. A decade later, the advent of samplers and home studios would mean that the potential quality to be achieved by do-it-yourself recording was completely transformed, and it became normal for dance records with slick production values to be made in musicians’ living rooms. However, the original DIY ethos survived in the tradition that exalts the lo-fi production values of, for instance, Liz Phair’s first album, the first three Sebadoh records, Daniel Johnston’s cassettes, the four-track recordings of Guided by Voices, and the peculiar mumblings of Jandek.

Some odd examples of faking it sprang up in response to the DIY aesthetic. In the immediate aftermath of the Sex Pistols, musical skill was looked down on, so many musicians pretended to be far more incompetent than they really were, for the sake of their credibility. The Stranglers, for instance, a UK band that predated the punk movement but immediately adopted its ethos, suppressed their prog-rock instincts and musical skill, playing in a thuggish, basic style on songs like “Peaches.”

One irony is that the Sex Pistols were far from incompetent themselves. Steve Jones played his guitar in a way that sounded simple because of its brutality but that actually took a great deal of musical understanding and competence to execute. The wall of sound he built on the Pistols recordings was quite an elaborate achievement, which in some respects owed more to Phil Spector than to Iggy Pop—the skill involved is demonstrated by how feeble many attempts to imitate him sounded.

While the Replacements were badly afflicted by the wish to seem incompetent, on a wider scale they were probably fatally hamstrung by their conflicted approach to music business success. One can interpret their career as a journey from heroic resistance to sellout wannabes or just as a missed opportunity. But as punk moved into the past, many bands still retained the purist diktats of those who had interpreted it as being fundamentally about authenticity and self-expression. Loserdom, musical brutalism, and rage would be the touchstones of rock played by white youths for decades to come, from postpunk to straight edge and from thrash to grunge.

PUNK, IN ITS CONFUSED regard for authenticity and its rejections of fakery, created a series of traps. For all its confusion, it was an exciting, revitalizing music. But it was also a simulation that came to be seen as authentic, a failure cult that wanted to reinvent music, and a progressive genre in which incompetence and emotional immaturity were badges of honor. These traps were inescapable, even though many of those caught in them created fascinating music—Nirvana would eventually get stuck in the most unbearable trap (as discussed earlier), but in their own ways, Public Image Ltd. and the Replacements demonstrated the problems well.

John Lydon avoided the cartoon tendencies of punk better than many others of his generation, but in the end it has been hard for him to break free from the restrictions of authenticity—restrictions he was forced to adopt as his means of escape from punk. He has been as haunted by the ghosts of punk as Donna Summer has been by those of disco. He first acknowledged this in 1981, when he started to perform “Anarchy in the UK” on stage again, playing with the idea that selling out by pretending to be Johnny Rotten was a suitably cynical act. In 1996, he eventually took this line of thought to a logical conclusion when he consented to re-form the Sex Pistols for their Filthy Lucre tour, something he had frequently claimed he would never do. In many ways it turned out to be a celebratory moment: finally free of their legal battles, the band was able to show a new generation that behind all the outrage they were a brilliant rock band that deserved their place in history. But it was also an implicit admission that whatever Lydon achieved, he has never truly been able to get away from the Pistols.

In trying to escape the original paradoxes of punk, Lydon had walked into a new one. Part of his means of escape was to attach himself to ideas such as self-expression, individuality, and authenticity. This was only one segment of the punk idea, but it was the element furthest removed from McLaren’s game playing and detachment. By defining McLaren as inauthentic and himself as authentic, Lydon was able to create a role for himself, though one that became a straitjacket in spite of his valiant attempts to escape from it. His audience has been suspicious of any attempt to do something merely entertaining or overly experimental and has been most satisfied when Lydon works in the sphere of personal expression and truth telling. While he is sufficiently cynical and emotionally secure to disregard this suspicion (his humor and ability to distance himself has always been his saving grace), it has certainly made it hard for him to depart from the idea of authenticity by more than a few degrees. When PiL made a different kind of record—Happy?—in which the experimentation was based around relatively standard pop structures, a large part of Lydon’s audience reacted with incomprehension. Anytime he appeared to drift off the road of personal authenticity in his music, those who carry the “true faith” have accused him of selling out. This has happened even when he has been honestly expressing his own confusion, as he did in “Rise,” singing “I could be right, I could be wrong.”

There is a degree of built-in friction in Lydon’s attitude to authenticity. Above all, he always wanted to express his individuality, but at the same time he rejected the self-absorption of grunge and other white rock, saying that music was worthless if it didn’t relate to other people. Surveying the music scene around him, he later commented, “People were changing and moving on. Why couldn’t I?” But it was difficult for audiences to perceive Lydon as anything other than the punk icon he had once been. In the same vein, he also wrote, “Audiences are far too fucking demanding on the people they like and dislike. The truth always lets them down because it destroys their fantasies.” One can see the frustration he must sometimes have felt at the way he was treated, and that his emphasis on personal authenticity was not as clear-cut as it might sometimes have seemed.

He understood that the self he was trying to convey to the world was not a simple, unchanging entity. “I always hoped I made it completely clear that I was as deeply confused as the next person.” His message was in fact far more complex than simple authenticity; he wanted to express himself, partially by showing the true confusion, the multidimensional aspects of splintered thought that underlie personal identity. While he has often been judged on the grounds of whether he is being a fake or the real thing, he has in fact been projecting ideas that defy analysis in these terms. His ideas of complex and fractured selves and of the incoherence of personal communication might have been easier to convey if he were not saddled with the obligation to continually demonstrate his honesty and authenticity. This perhaps explains why his musical career feels not quite to have achieved all it could, even though he has been an influential artist who was fascinating to observe.

Since the Pistols re-formed, he has continued to play around with public expectations, threatening to take the Pistols to play a gig in Baghdad in the run-up to the invasion of Iraq and constantly challenging the way in which the press tend to typecast him. More recently, his career has taken some odd turns. His fascination with the medium of television was demonstrated by his involvement in the Rotten TV project, a loosely defined experimental program he worked on for the station VH1 in 1999–2000. Even so, it came as a surprise when he agreed to appear in the UK reality show “I’m a Celebrity, Get Me Out of Here!” a show that regularly requires its celebrities to participate in ludicrous games to win food and privileges. Seeing Lydon play a game in which he had to pick up plastic stars in an ostrich pen to win meals while the birds pecked at him unmercifully was one of the more surreal television moments of recent history. But it was his acerbic performance there and an unexpected communion with the Australian jungle that led to his next gig: presenting wildlife shows for the UK’s Channel Five.

Incongruous as it may seem, Lydon appeared at his happiest and most unaffected in this role. Perhaps because the weight of his musical past was not an issue, he finally seemed able to focus his considerable personality on something beyond the solipsistic ideas of celebrity and self-expression. Playing with apes in the jungle or watching sharks from a metal cage under the ocean, John Lydon at last seemed free to actually be himself, without endlessly having to prove that he was being himself.