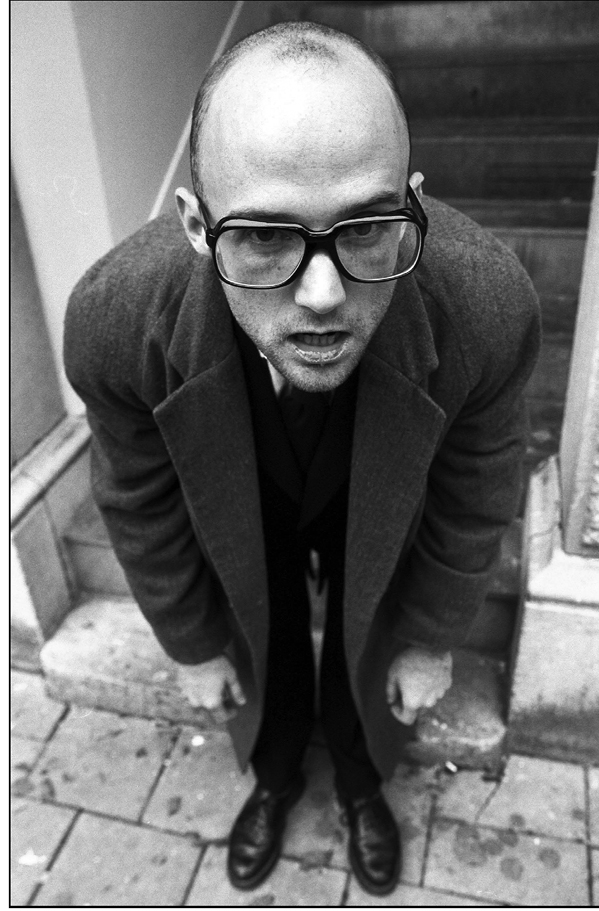

Paul Bergen / Redferns

CHAPTER TEN

PLAY

Moby, the KLF,

and the Ongoing Quest

for Authenticity

New York, 1998

. . . rockroll as a system of thought. A

system!—the ultimate system—the one that eats its own guts out.

RICHARD MELTZER, A Whore Just Like the Rest

I have nothing in common with myself.

FRANZ KAFKA, Diary

AS A YOUNG MUSICIAN, Richard Melville Hall played in punk, reggae, new-wave, speedmetal, and industrial bands, then became a hip-hop DJ. As Moby, he finally found success as a techno artist with strong alternative rock tendencies. But nothing could have prepared him for the worldwide success he found with his 1999 album Play. Essentially a pop dance record, it has snatches of punk rock, trip-hop, and even baroque piano fugues. But the most notable aspect of the album, and the one that helped it to achieve its great success, was its use of samples taken from the field recordings of John and Alan Lomax.

Moby weaved old cappella and voice-and-percussion samples into accessible pop grooves. As a result his songs gained a cachet of authenticity entirely borrowed from their source material. Before this, most techno artists who had sampled primitive recordings did so with a dose of irony, but here the music was presented straight. The strong emotions evoked by the original recordings partially survived translation into a new environment—thus the songs have an impact that far exceeds what we would normally expect from the clinical production and straightforward songwriting evidenced elsewhere in the album.

Moby represents the marriage of dance music to both punk and puritan ideals. The DIY sampling and production that had been so liberating in recent dance music became a moral imperative for Moby, just as it had for the punks. In interviews, Moby continually stressed both his vegan and Christian puritanism and his DIY credentials (the album was recorded entirely at Moby’s New York home over a period of eighteen months; it consists of eighteen songs culled from over two hundred).

When Play was released it went to Number One in many countries, sold ten million copies and three million singles, and propelled Moby to the position of the world’s best-selling dance musician. In turn, the tracks were sold as commercials for a wide range of luxury goods. Producers of commercials recognized that while the music was modern and unobtrusive, it had an emotional effect on the listener, which made it ideal for underpinning the selling moment.

Amusingly, Moby has defended his music’s ubiquity in advertisements on the basis that it is a kind of guerrilla marketing, compensating for his underdog status: “The music I make doesn’t get played on the radio, especially in the United States. If you’ve spent a year and a half working on a record and you’ve poured your sweat and your blood into it and you’re really proud of it, you want people to hear it.” There’s nothing wrong with making music that is successful in a commercial context, but this justification reveals a degree of dissonance between his success and his purist ideals: prior to his first commercial license of a song in 1995, he had said, “I had been really opposed to the idea of letting my music be used in advertisements. I had been a punk rocker growing up, and I always avoided things that sort of reeked of selling out or compromise.”

Moby also demonstrates a degree of doublethink about the way that he used the field recordings to add authenticity to his music, recognizing that some critics have made the negative comparison between his approach and Paul Simon’s in Graceland. As ever, there is a touch of the patronizing missionary coming to rescue the humble natives in such collaborations even when, as with Moby, the collaboration is with artists from long ago. He disarmed one interviewer’s questions on the subject by replying that “Maybe what I have done is wrong. And if someone can make a compelling argument as to why what I’ve done is wrong, I hope I am open-minded enough to listen to it. The only thing I would say in my defense is that I was quite genuine and naive in my approach and I am not being so presumptuous to lay claim to any aspect of the African American experience.”

When Norman Cook (aka Fatboy Slim) married an affecting a cappella vocal to modern dance music on his track “Praise You,” he was less tactful and made the mistake of giving an interview in which he claimed that he was taking old or forgotten songs and improving them. Camille Yarborough, whose soul/gospel song provided the main sample for “Praise You,” was very much alive and hit back at Cook’s slur, pointing out how heavily his song depended on her original creation. And comparing the two tracks, the Fatboy Slim one does seem like little more than larceny. Moby has the advantage of using the voices of a distant age. There is no one left to speak out for the original singers. But neither this fact, nor the fact that Moby understands the possible criticism, means that his use of these samples is not problematic.

Moby’s success came about because he clothed dance music—which had been since the advent of disco the most transparently and gleefully “inauthentic” of musical genres—in the trappings of authenticity. He used a ragbag of the hallmarks of authenticity: old black roots music, slide and acoustic guitars, vegetarian diatribes in the liner notes, navel-gazing lyrics (as on “If Things Were Perfect” and “The Sky Is Broken”), even his emphasis on autobiography on his Web site, which includes a personal journal. But at the same time, he successfully diminished the unbridled passion that made blues and gospel seem so exotic for most of the twentieth century, and thus made the music more palatable. With Play, Moby managed to homogenize almost every significant “authentic” musical genre—blues, gospel, punk, hip-hop, even folk—into a melange perfect for mass consumption. No wonder the advertising executives loved him.

Play, like Buena Vista Social Club (not to mention the TV show American Idol), demonstrates the degree of homogenization of music in recent years. They all recycle music of the past into a bland product for the widest possible audience. And this tendency is ubiquitous. Even such an outrageous and once offensive punk anthem as the Ramones’ “Blitzkrieg Bop” is now used in a TV commercial—just another sound to be sampled. One can’t help but wonder whether the Sex Pistols’ graphic abortion diatribe “Bodies” is next.

But unlike American Idol, both Play and Buena Vista Social Club derived their success from the quest for authenticity, because today, despite the many changes in the music business and recording processes, and despite all the apparent toleration of perceived inauthenticity that American Idol epitomizes, this quest still has enormous power.

WHEN WATCHING a show such as American Idol (or, in the UK, Pop Idol), we can feel as though authenticity doesn’t matter any more. Reality television and pop music have melded together in a seamless blend of light entertainment. Like VH-1’s Behind the Music, the show reveals and glorifies the manufacturing of music. The pop music business has momentarily succeeded in turning its darker arts into a central achievement to be celebrated as the creation of successful pop acts and records is seen as an end in itself. Celebrity is the ideal, and the struggle to attain success is treated as more important than the actual music.

But even American Idol is haunted by questions of authenticity: the constant cutting between the performances and the backstage “private” moments emphasizes the idea of the performance expressing the artist’s true self in a way that American Idol’s many predecessors (going all the way back to Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Show in the 1940s) wouldn’t have. Nor would those earlier shows have had the judges urging the performers to be themselves, to show us their real selves.

A century ago, not many people were concerned with how authentic a piece of music was; now the concern seems, at times, overwhelming. Issues of authenticity have crept into every kind of music we listen to: they’ve been ubiquitous in country, rock, and hip-hop for decades, but with Moby they infiltrated dance music, and now pop singers such as Ashlee Simpson have to justify themselves with album titles like Autobiography and I Am Me.

Even at its most superficial, contemporary pop music embraces the idea of confession and therapy through music. Simpson, a lightweight pop star and reality TV graduate, was widely derided for a lip-synching debacle on Saturday Night Live. So on her second album, she recorded “Beautifully Broken,” a fairly weak riposte to her critics. Of course, much of the controversy recalls the hypocrisy of previous attacks on the Monkees and the Backstreet Boys. Critics who are perfectly aware of all the reasons why Simpson was likely lip-synching reacted in mock-outrage and schadenfreude at her televized humiliation. In response, the songs recorded by Simpson show increasing self-absorption and a dependence on personal detail for their effect. And Simpson is far from alone in trying to reveal her life to the world, no matter how uninspiring it may be. While Avril Lavigne’s first album of teen grunge lite was a success largely because of the quality of the songwriting—songs like “Complicated” and “Sk8er Boi” were supplied by the Matrix songwriting team—she was stung by criticisms that she was a manufactured star and insisted on co-writing the songs for her second album to prove that she was for real. Inevitably the result was a weaker album, with self-referential songs that continued Lavigne’s angsty pose, but with less pop glitter and focus. Meanwhile the UK’s pretend teen punksters Busted joined the long list of chart bands that have proclaimed their creative contribution to their (co-written) songs in an attempt to counter accusations that they were fake.

These are all minor examples, but they demonstrate the way that even the most transparently manufactured pop musicians look for fig leaves of authenticity. And this leads to a larger question: can pop music even exist without the idea of authenticity anymore? It seems to have played such a central role in the story of rock and pop that it’s hard to imagine music without it.

ONE EXAMPLE of how peculiarly difficult it can be to escape from the effects of this quest for authenticity is the career of the KLF.

A hugely successful band in the early 1990s (they sold more singles worldwide than any other act in 1991), the KLF publicly quit the music business while they were still at the peak of their success and went on to demonstrate their contempt for the whole charade in the most extreme way they could imagine. They announced their departure with a derisive performance at the 1992 Brit Awards (the main British music business ceremony). A freshly slaughtered sheep (plus eight gallons of blood) was laid at the entrance to the post-awards party. Bill Drummond, the former A&R man and manager who cofounded the band with Jimmy Cauty, later claimed that his original plan had been to cut off his own hand and throw it into the audience while performing. Two years later, in July 1994, on a remote Scottish Island, the two band members deliberately set fire to one million pounds in cash (supposedly the largest cash withdrawal in UK history), filming the event for posterity. It was most of the money they had made from their music. What inspired this spectacular run of self-destruction?

In the early 1990s, the KLF had used samples from a bizarre variety of sources to create a series of clever but absurd hit records that contemptuously recycled the same themes and tunes with only minor variations. They were one of the most anarchic, perverse bands of the time. Perhaps only the experimental American group the Residents have matched their disdain for celebrity and personality within music. KLF’s initial singles coincided with the explosion of sampling in pop, and they were gleefully unrestrained in their use of the new technology. Borrowing or stealing from any genre, artist, or sound that took their fancy, they created sardonic, absurd pieces of dance music that were nonetheless catchy and funny. After their first hit they released a book called How to Have a Number One the Easy Way, and it seemed that in their world-weary cynicism they had indeed found the formula for success.

They regularly changed names, flouting the idea of celebrity, and their music became more and more bizarre before they quit the business altogether. They married the theme from the TV show Doctor Who to a sample from seventies glam rocker Gary Glitter to create “Doctorin’ the Tardis,” a dadaist house tune fronted by two police cars. They resampled their own songs to create new variations, persistently reusing themes such as “What Time Is Love” and the “Mu Mu” chant of their absurdist alter egos, the Justified Ancients of Mu Mu. They even managed to persuade Tammy Wynette to sing on their hit “Justified and Ancient” (“They’re justified and ancient, and they drive an ice cream van”). It’s hard to imagine a band that so completely skewered the absurdity of pop music while simultaneously creating gloriously funny hits that actually seemed to be a part of the mainstream dance scene that they were parodying.

They didn’t turn anticorporatism into a badge of honor, but their whole career displayed a radical disdain for the values that sustain music as a business. They also retained a large degree of control of their own music, at least in the UK, eventually deleting their entire back catalogue there and burning most of its profit. Why did they do it? Because they could. Having briefly embodied the forces that threatened the music business, the KLF departed, leaving behind a music scene in flux.

The great sci-fi writer Philip K. Dick once pondered what would happen if someone sneaked into Disneyland and replaced the fake animals with real ones. How would people react to the “fake fakes”? This is not a widespread problem in popular music, but U2 is one example that comes to mind: from Zooropa onward they strived to project a showbiz fakery that was far removed from their true earnestness in a self-conscious attempt to get away from their po’-faced image.

The KLF was a different kind of “fake fake.” When they were at their peak, one always had the sneaking suspicion that behind the glitz, the sloganeering, the sheer absurdity of their image, there was something real going on, even if it wasn’t always clear exactly what it was.

Bill Drummond spoke recently of the triumph he felt when, after a typically absurd and self-defeating comeback performance, he met a journalist who had once been his number-one fan and who had even written a book about the band. After the performance, the journalist stayed with them as they daubed the walls of London’s National Theatre with one of their typical slogans (“1997: What the fuck’s going on?”). Shaking hands at the end of the evening, Drummond realized that during the evening he had managed to disappoint even this great admirer. Looking into the fan’s eyes, he caught a glint of “disillusionment, as real and pure as disillusionment can get.” In his book 45, he goes on to say that “that moment of disillusionment was maybe our greatest creation. Without that final state of disillusion, the power and glory of pop is nothing.”

There is a kind of anger that musicians can feel toward their audience when they sense that the audience is either trapping them or perceiving only a cartoon version of what they want to project. Think of Kurt Cobain, at a huge Brazilian gig, refusing to play “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” the hit that every audience demanded of him, and instead performing a cover of Queen’s “We Will Rock You,” with the words amended to “We Will Fuck You.” Think of Sid Vicious walking those showbiz boards in The Great Rock and Roll Swindle, singing “My Way” in his Sinatra suit, then firing a gun indiscriminately on the audience—an act reprised by KLF, who fired blanks on the audience from an automatic rifle at the 1992 Brit Awards.

Disillusionment is the realization that something that seemed real is not. There is a paradox here: the KLF’s number-one fan had looked up to Bill Drummond as a hero, as a prankster genius, as the scourge of the music business, and as a political idol. But when Drummond finally managed to disillusion him, the number-one fan belatedly realized that Drummond was none of these things.

He was only a real person after all.

THE KLF DID everything in their power to deconstruct conventional notions of celebrity, success, fan worship, and even authenticity itself, forcing their followers to confront their most cherished assumptions about the rules of popular music. Their self-destructive and perverse behavior and their spectacular sabotage of their own success seemed to be part of a master plan. On the other hand it may simply have been the gut reactions of two performers who stumbled into success at the exact moment when they despised the music business too much to behave any other way. In the end they took solace in their own demise. By setting themselves up as anti-establishment heroes and then failing to live up to their own hype, they had obliged their fans to realize that, by extension, all performers are only playing a part, “faking it.” For the KLF, it seemed that only by disillusioning one’s fans could one be truly real.

But somehow we refuse to be disillusioned. The quest for authenticity has always been our quest as listeners just as much as it has been that of musicians. It has informed and shaped our tastes, and it has placed requirements upon the performers we follow. And it seems unlikely that it will ever go away.

Our own tastes have changed from when we (the authors of this book) were younger. Large parts of our record collections we listen to only rarely, whereas other genres and artists that we might once have disdained have become staples of our everyday listening. And then there are other artists we loved when we were younger that we still love to hear, even if our perceptions of them have changed.

One of the axes along which our respective views on music have changed is authenticity. When we were younger, both of us mostly accepted the quest for authenticity in music as a fundamental way of judging artists. Honesty, self-expression, and cultural integrity were essential parts of our basic critical tools. In preferring Hank Williams to the Carpenters, the Velvet Underground to the Archies, or Nirvana to KISS, we were making judgments based on an idea of which artists were more real, less fake.

Over time, as our tastes changed, we found this distinction breaking down and becoming increasingly meaningless. Hugh rarely sits at home and listens to the Archies (well, maybe sometimes . . . ), but he does listen to the Carpenters and ABBA; Yuval still listens to Neil Young, but often prefers Elvis and disco singles. Both of us realized that, no matter how gritty and real they are, we don’t really enjoy listening to Hank Williams or Robert Johnson anymore, although Hugh still loves Johnny Cash and Yuval still loves Bob Dylan. These are personal prejudices, and everyone will have personal examples. But the key point is that over time the importance of authenticity to our judgments has to some degree faded. Not that we always prefer inauthenticity to authenticity, it’s just that we both see far more complications in making these judgments at all.

A late Johnny Cash recording happens to provide a good example of how complex it can be to judge authenticity. On American Recordings, Cash took a stripped-down acoustic approach that derived from the MTV Unplugged aesthetic of authenticity. With producer Rick Rubin he chose a range of songs that worked well to showcase his legendary voice in an emotional, mature setting. It was a very self-conscious attempt to create an “authentic” sound to match the audience’s expectations of the elder statesman’s status. Years of music being judged on the grounds of authenticity have taught producers how to use basic production tricks to accentuate authenticity—by using traditional-sounding effects and acoustic sounds, and by allowing rough edges to show. American Recordings used many of the same production values as Buena Vista Social Club. And it worked: the records in the series rejuvenated Cash’s career. They carry a strong emotional charge, even though it is clear at times that one’s emotions are being exploited by the choice of songs and arrangements. Interestingly, the records were all but disregarded by the country establishment; they were instead admired by a new generation of rock fans.

In “The Mercy Seat,” Cash took on a Nick Cave song about incarceration and execution. The song vividly describes the dying moments of a convicted murderer who spends the song proclaiming his innocence, only to reveal the guilty truth in his final moment. Cave blatantly uses blues and country music as signifiers of emotion and authenticity. But his original of “The Mercy Seat” is a histrionic production that does little to disguise its bogus credentials. The song is, after all, by an Australian songwriter who specializes in facsimiles of Southern American music and accents, pretending to be a criminal with lunatic tendencies. It is comic in a very dark way, but it’s not really convincing.

In Cash’s hands, something strange happens to the song. Cash is much older than Cave and is known for his miserable childhood in the Southern cotton fields. In spite of his carefully cultivated outlaw image, he never served a jail sentence, although he had a few overnight stays in the cells in his youth. But he was known for “Folsom Prison Blues” and for his electrifying San Quentin performance that helped to cement his reputation. Cash was also religious, something else that stayed with him from his childhood, especially after the horrific death of his brother in an accident.

When Cash sings “The Mercy Seat,” there are no histrionics. The biblical references, the reluctant recognition of death approaching, and the song’s bitter details of prison life all suddenly ring true. The song is convincing in a way that Cave’s version could never be.

Is it authentic? Of course not. It’s not an honest personal account, and it’s a secondhand rendition of a distant cultural facsimile. But our knowledge of Cash and his performance of the song give it an emotional charge that rides through the inauthenticity, creating an affecting drama, even if it is not an authentic document.

When one hears this song, judgments of “real” and “fake” become all but meaningless. Because realness has so often been seen as a morally superior quality in music, it feels uncomfortable, like a kind of apostasy, to point out the inauthenticity in a song like this. It is probably possible to really appreciate the song only if one lays aside all notions of authenticity and hears it as a performance, pure and simple.

BUT ONE CAN’T always put authenticity to one side. Tastes formed on a base of authenticity change only slowly, and many old prejudices survive. Most rock fans still crave authenticity, and many have become increasingly extreme in their quests. Some, disillusioned with the degree of fakery even in the most seemingly authentic performers (e.g., Kurt Cobain), have turned instead to idolizing those who couldn’t fake it even if they tried—so-called outsider musicians.

Outsider musicians are by definition authentic: these hopeless aspirants to pop music fame have talents that are foreign to all conventional definitions of “good music,” and their creations are sincere and occasionally inspired. These are artists with no conventional training in music—and often with no talent for it either—who buck the odds and make music despite their handicaps, which range from mental instability to tone-deafness to obsessions with creatures from other worlds. The results can be wildly entertaining by any standard, and their sweetness and naïveté can be hard to resist.

Daniel Johnston is one example of a performer who has gained a cult following based on his outsider status. Revered by Kurt Cobain among others, his background of mental instability gives his music a fractured feeling. The lo-fi, homemade productions for which he was first known seem absolutely direct and unrefined. As a result, his music seems to carry a charge of honesty and openness that fans of indie music were finding increasingly hard to perceive in more cultured performers. Johnston’s high status in indie rock circles says much about that community’s thirst for authenticity.

The search for authenticity in the rural performers recorded in the late 1920s, or in modern-day world music, has often been a search for the last musicians untouched by self-consciousness. And the adherents of outsider music, like the folk fans, are not immune to taking a patronizing attitude toward their largely primitive protégés. Yet these “talentless weirdos” may not be irrelevant: it could easily be argued that Thelonious Monk, Ornette Coleman, Captain Beefheart, and Syd Barrett of Pink Floyd were all outsider musicians to some degree. It may seem unlikely, but from where else but “outside” can true musical innovation come? Unfortunately, few of the outsiders praised by their fans can be called innovators; most of them are simply naïve. Outsider music is a fascinating alternative, but by definition it’s unlikely to ever truly enter the mainstream. It does, however, illuminate to what lengths today’s music fans will go in search of authenticity.

AS WE’VE NOTED, there are two sides to the problem of authenticity in music: how ideas about authenticity affect the listener, and how they affect the performers themselves. The two can’t be completely disentangled, because part of most artists’ motivation is based on the perceptions and approval of the audience. But one can at least consider the two sides of the issue separately.

In this book, we have considered the various snares that awaited artists as different as John Lydon and Donna Summer, John Lennon and Jimmie Rodgers. We could go on to write similar chapters about such artists as P J Harvey, Merle Haggard, and U2, all of whom have reacted to the quest for authenticity in unique ways. And a whole book could be written about authenticity in hip-hop, which has been based largely on a semi-autobiographical approach, harnessing the anger and energy of punk without going to its ideological extremes, yet complicating the question with its glorifications of violence and luxury.

But we have mostly avoided discussing the quest as it applies to us listeners; without some kind of sociological survey, it’s hard to tell whether most of us tend to prize authenticity or whether it’s simply those of us who grew up in specific times and places.

So for those of us who do still prize authenticity to one degree or another, is it possible to put authenticity to one side for a while? To refuse to accept that “authentic” is always morally better than “inauthentic”? If you get up, turn on the radio, and listen to some music you haven’t liked before because it struck you as “fake,” how do you feel now? Liberated? Bored? Scared? Maybe even entertained? Is it possible to just listen and react to it without worrying about why you do so? And if you are enjoying music that you would normally regard as fake, do you feel ashamed?

When we’re young, a large part of our original motivation in discovering music comes from trying to find out about our identity—perhaps to fit in, or, in contrast, to differentiate ourselves from the rest. The musical morality we adopt at an early age often becomes enshrined, making it hard to change our views later on. From this comes the notion of “guilty pleasures”—any music that we regard as inauthentic but still enjoy becomes a shameful secret, rather than something we can honestly admit to liking. But labeling music in this way allows us to retain the simple identification of music as real and good or fake and bad (but occasionally secretly enjoyable), and thereby prevents us from analyzing more deeply the reasons why we like this music.

We’re not trying to say that it’s always wrong to like music on the basis of how authentic it seems. Often in talking about authenticity we are also talking about other attributes that can be important to us. Music can be great to listen to exactly because it is heartfelt, emotional, honest, personally or culturally revealing, and so on. It’s just that when we aggregate all these into an ideal of authenticity we can lose sight of the fact that some of the things that make us judge music as inauthentic—such as theatricality, glamour, absurdity, pointlessness, and cultural cross-pollination—can also enrich our musical experience considerably.

WHICH BRINGS US back to Moby. One of the best songs on Play is “Run On,” which essentially takes a track by the Landfordaires, a gospel group, and adds some drums, piano, turntable scratching, and a rather surprising slide guitar. Moby almost spoils the song when he adds synthesized strings at the end, but it’s still far more fun than most of Play. There’s nothing overly sanctimonious about this cut—it’s truly playful, and rather than homogenizing or deadening what it samples, it simply supplements it in an amusing way.

But it’s a song about keeping it real: “Better tell that lonesome liar,” Bill Landford sings, “tell them God Almighty gonna cut you down.” It’s about avoiding sin and God’s retribution. Despite how much fun the song imparts, the singer is being dead serious, and so is Moby. This is a song about death and salvation, subjects that can’t be more important. And in the middle of it, Moby interjects another gospel moment: a woman’s voice singing “What is the real thing?”

All this is to say that perhaps there’s yet a third way to listen to music. It’s not only a choice between valuing authenticity or not. So many artists nowadays, from Moby to P J Harvey to the KLF, are consciously playing with ideas of authenticity. Why shouldn’t we, as listeners, do the same? A good part of the pleasure we get from a song like “Run On”—or Johnny Cash’s “The Mercy Seat,” or that prototypical outsider music album the Shaggs’ Philosophy of the World, or the next semiconfessional celebrity pop hit or gangsta rap single—is in figuring out what’s authentic and what’s not authentic about it. It’s a new game we can play with the music we listen to. All it requires is that we keep our ears—and our minds—as open as we can.