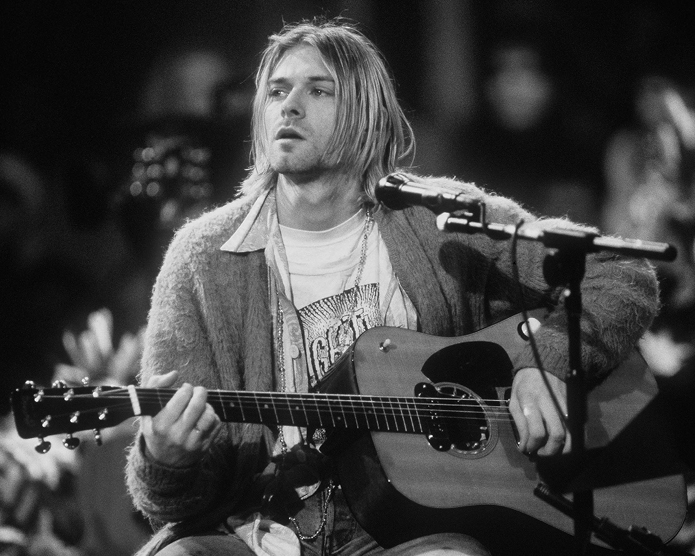

Frank Micelotta / Getty Images

CHAPTER ONE

WHERE DID YOU

SLEEP LAST

NIGHT?

Nirvana, Leadbelly, and the Allure of the Primeval

New York, November 18, 1993

It would be a tragedy to spend your whole life desperately wanting to be something that you already were all along.

DAVID BERMAN, “Clip-On Tie”

LIT BLACK CANDLES AND hundreds of lilies decorated the stage. The television lights burned bright.

Nirvana’s MTV Unplugged special had started tentatively, with Kurt Cobain clearly nervous, and the band members and additional musicians looking ill at ease in the funereal stage décor. But their confidence—and the audience’s appreciation—had built steadily, and the performance had turned into a success.

As a finale, Cobain led the musicians through a chilling, passionate, but peculiar dirge in waltz time, first introducing it as a song by “my favorite performer,” Leadbelly, a black singer lionized by left-wing white folk-music fans in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s. He then refused to return to the stage for an encore. As a result, “Where Did You Sleep Last Night” was the last song he performed that night. Technically, it may not have been his swan song—there was one more unfinished recording session in Seattle in January—but it was so powerful and emotionally charged it could have been.

Nirvana had always appeared absolutely genuine in everything they did, and this was one of their attractions for an audience jaded with the contemporary music scene. Cobain’s songs were often autobiographical in a fragmented, allusive way, but they always seemed highly personal. His words not only reflected his pain, but they were sung with a raw, stripped-down passion. He had gone to tremendous lengths to “keep it real,” to rebel against commercial expectations, and to expose his problems to the public.

As Cobain looked out at the Unplugged audience who, unusually for a Nirvana gig, were seated, visible, and unnervingly close to the band, he was aware that they knew a great deal about his private life, both from what he had chosen to reveal and from what had been made public without his consent. When he mentioned “warm milk and laxatives, cherry-flavored antacids” and muttered “I have very bad posture” in “Pennyroyal Tea,” they knew he was talking about his health and drug problems. If every detail wasn’t explicit, they could fill in the gaps because of the gothic soap opera that his life as half of a celebrity couple had become. The normal embarrassment of being exposed on a stage, which Nirvana could cover up in noise and aggression, would have been magnified by the naked circumstances of this performance. Most musicians have had nightmares about finding themselves on a stage alone and unprotected. It’s no surprise that Cobain was slightly nervous.

His solo performance of “Pennyroyal Tea” marked the moment the Unplugged performance moved into a higher gear. His guitar playing was clumsy in places and he missed a chord or two, but the stark emotion in his voice was inescapable. A couple of songs later, he performed “Polly,” the story of a rape. The song is shocking not just because it is sung from the rapist’s point of view but because of the boredom the narrator conveys. Cobain was clearly not drawing directly from personal experience, but the song’s nihilism and desensitization seemed overpowering. Even this extreme a song was emotionally honest about a disturbing state of mind, and his listeners recognized and acclaimed this.

The truth is always complicated, however, and between Cobain and his public persona were conflicts and contradictions. In his interviews, and even in his autobiographical songs, he was prone to embellishment and self-mythologizing: for example, he claimed to have swapped his mother’s ex-boyfriend’s guns for his first guitar, but he’d had a guitar for a long time by then; and he claimed to have lived under a bridge during his homeless days, almost certainly an exaggeration. His anticommercial stance was at odds with his long-standing desire for success, and the tension between these two led him to alternately celebrate and despise his achievement. When he was younger, he had concealed his commercial ambitions and his liking for “uncool” bands from his punk friends in order to retain his perceived integrity—for instance, he didn’t mention in those circles that he wanted his own band to be “bigger than REM or U2.” Later, in the same spirit, he castigated himself publicly for selling out while continuing to strive for further success: when he appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone, it was in a T-shirt reading “Corporate Magazines Still Suck.” In the interview inside, he said, “I don’t blame the average 17-year-old punk-rock kid for calling me a sellout. I understand that. Maybe when they grow up a little bit, they’ll realize there’s more things to life than living out your rock & roll identity so righteously.” In the same interview, however, he criticized Pearl Jam, who were currently rivaling Nirvana’s success, in similar terms: “I would love to be erased from my association with that band and other corporate bands like the Nymphs and a few other felons. I do feel a duty to warn the kids of false music that’s claiming to be underground. They’re jumping on the alternative bandwagon.”

Success in the music business is rarely achieved without minor compromises and adjustments of attitude along the way. Kurt Cobain, like many other artists, wanted the fans to see a particular version of his self—something more like the person he had been before he started to succeed than the person he was now. Even though he was more obdurate and successful at preserving his self-respect than many musicians, he still felt compromised. He defined honesty as not putting on an act, and felt that performing when he no longer felt enthusiastic about it was a shameful lie.

But for all the complications, Cobain’s desire for authenticity, real and perceived, was matched by that of his fans, who saw him as the real thing in a fake business. It was only appropriate, then—if somewhat ironic—that his swan song was performed on MTV Unplugged. Launched four years earlier and continuing to this day, Unplugged was conceived as a response to the public perception that the contemporary music scene was obsessed with image rather than content. MTV had done more than anyone to foster this perception—the advent of twenty-four-hour music programming and the massive influence the station attained in the 1980s had multiplied the power of video to the point where managers spent more time arguing over the video budget for their bands than they did worrying about the music. So for MTV to present itself as the guardian of real music was both unexpected and bizarre.

The idea behind the show was to strip away as much of the technical and studio assistance that protected the artist as possible. The artists would perform their songs, preferably with only acoustic instruments, or at least (as with Nirvana) in a quieter, more stripped-down form; the audience could then judge whether or not these were musicians and singers who could really perform. Nothing was really unplugged—not only were there electric instruments, microphones, and other sound output and recording devices, but there was, of course, all the other electronic video equipment that television can’t exist without. But in an age when tracks are created on computers, all instruments and sounds can be sampled and artificially modified, and vocal performances are pasted together from banks of tape using autotuning to correct imperfections, people want to see artists in “real” conditions. Some performers have thrived more than others in the artificially intimate conditions. For instance, Tony Bennett gave an old pro’s performance that made full use of his constricted band, while REM, on their first appearance in 1991, looked like buskers merely pretending to be REM.

Nirvana had little to prove in terms of authenticity, although it was fascinating to see how they would respond to an environment that robbed them of the sheer volume of their live gigs. In the end, they succeeded, and their performance became a classic recording, released shortly after Cobain’s death. The stage decorations depicted on the cover and the preoccupation with death apparent in his choice of songs made it an eerie record to listen to so soon after the tragedy.

So given the circumstances, what was it about “Where Did You Sleep Last Night” that fascinated Kurt Cobain and led him to play it on this occasion? Why did he choose that song as his closing statement? Why did he call Leadbelly his “favorite performer”? And what echoes of bygone quests for authenticity can we find in all this?

“WHERE DID YOU Sleep Last Night” is Leadbelly’s version of a song commonly known as “In the Pines,” which probably dates back to the 1870s and has been recorded hundreds of times by performers in almost every genre. As Dolly Parton told Eric Weisbard for the New York Times, “The song has been handed down through many generations of my family. I don’t ever remember not hearing it and not singing it. Any time there were more than three or four songs to be sung, ‘In the Pines’ was one of them. It’s easy to play, easy to sing, great harmonies and very emotional. The perfect song for simple people.”

Kurt Cobain was not such a simple person, although he sometimes liked to pretend he was. He had been performing the song since the late 1980s, and had accompanied Mark Lanegan, the leader of the Seattle rock group Screaming Trees, on guitar for a version on Lanegan’s 1990 album The Winding Sheet. At one point the two had tried to start an offshoot band and had recorded three songs, all by Leadbelly, before other projects prevented them from continuing, and only this song was released. Lanegan owned a copy of Leadbelly’s original 78-rpm release of the song, recorded in 1944; Lanegan and Cobain probably listened to it many times. Cobain had also performed the song with Courtney Love at Hollywood’s Club Lingerie, on the only occasion the two sang together in public.

The song is about a girl who goes into the pines, “where the sun don’t ever shine,” after her husband’s decapitation by a train. This fits well with Cobain’s fascination with death and other grisly subjects, and is given an additional, distressing resonance in retrospect by the near-decapitation caused by the gun he used to kill himself. Throughout his last year he made many mentions of suicide and guns, and it is clear that the idea of killing himself was in his mind long before he carried out the plan.

Cobain made a few modifications to Leadbelly’s version: he changed the first chord of each verse from major to minor (occasionally adding a fourth), thus imbuing the song with an even more melancholy tone; he slowed the tempo way down, doubling the song’s length and also increasing its sadness; he changed the repeated words “black girl” to “my girl,” thus erasing Leadbelly’s racial perspective (he also made a few other insignificant lyrical changes, such as changing “driver’s wheel” to “driving wheel”); after singing all the verses of Leadbelly’s version, he repeated some of them, first sotto voce, then raising his voice an octave (a trick one can trace back to Skip James’s 1931 “I’m So Glad”), lending the song an air of complete desperation because of his straining to hit the high notes; and he sang the song’s last words (“I’ll shiver the whole night through”) in half-time, his voice completely hoarse and ragged, thus adding an undeniably dramatic flourish to what was, in the original, only plain repetition.

The result is a terribly haunting and emotional performance. Cobain’s anguish is unmistakable, yet there’s no self-pity, as in, say, the words to “Pennyroyal Tea.” His torment takes on a broader meaning because of the strangeness of the lyrics and the vivid imagery: “His head was found in the driving wheel, but his body never was found”; “In the pines, in the pines, where the sun don’t ever shine.” The combination of Cobain’s passion and the rich cultural heritage of “Where Did You Sleep Last Night” made for an unforgettable production.

THE BLACK GUITARIST and singer Huddie Ledbetter, more commonly known as Lead Belly or Leadbelly, became famous in part because his repertoire was so large and varied. He was considered a kind of repository of American folk music, having learned many of his songs from prisoners, both black and white, while serving time for murder. Folklorists John and Alan Lomax helped him when he was released from jail in 1934, and then took him on tour; playing in concert halls and folk-song circles, he was billed as an exemplar of the riches of black song. Never mind that Leadbelly enjoyed no success whatsoever with his African American peers (the few “race” records he cut for ARC sold poorly, and his stint at Harlem’s Apollo Theater was a complete flop); he was lionized by white folk singers, collectors, and Communist Party members, with all of whom he had very little in common.

Although Leadbelly had considerable talents—a powerful, dynamic, expressive voice; a resonant, confident, and energetic guitar style; a prodigious musical memory; an astonishingly varied and rich repertoire; a strong sense of rhythm—his songs didn’t swing. Not at all coincidentally, Leadbelly achieved fame by playing primarily to white audiences. In some ways the scenario of John Lomax bringing his charge on tour was reminiscent of the pre–Civil War career of Blind Tom, the Negro slave and piano prodigy whose owners made of him one of the biggest performing sensations in American history. But crucial to Blind Tom’s success was his sophistication, while crucial to Leadbelly’s was his lack thereof.

Perhaps another comparison is more apt, the one Nolan Porterfield makes in his biography of John Lomax: Leadbelly was seen as a real-life King Kong. The movie King Kong had been a huge hit just two years earlier; as Porterfield writes, “a savage being, primitive and violent, is discovered by a white man, put in bondage, transported to Manhattan, and placed on public display.”

Indeed, whites saw in Leadbelly, who had not only been convicted of murder in 1918 but of attempted murder in 1930, the epitome of the “primitive”—the violent, primordial black man who sings old, deep, unfathomable songs directly from his soul. Back in the eighteenth century, Jean-Jacques Rousseau popularized the idea of the “native” as a “noble savage,” the embodiment of Western virtues, uncorrupted by civilization; the concept was applied equally to Polynesians (see Melville’s Typee), American Indians, and Africans, enslaved or not. But by the twentieth century, with the influence of Darwin and Freud, it was primarily the Negro who had become idealized, and this time as the primitive—brute, savage, untamable—pure id, and therefore profound. You can see this idealization in the vogue for African art, in Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon, in the career of Josephine Baker, and perhaps most vividly in Vachel Lindsay’s 1914 “The Congo: A Study of the Negro Race,” the poem that made him famous. In its three sections, entitled “Their Basic Savagery,” “Their Irrepressible High Spirits,” and “The Hope of Their Religion,” Lindsay tried to collapse all distinctions between Vaudeville cakewalks, Harlem society, and the Congo. He began:

Fat black bucks in a wine-barrel room,

Barrel-house kings, with feet unstable,

Sagged and reeled and pounded on the table,

Pounded on the table,

Beat an empty barrel with the handle of a broom,

Hard as they were able,

Boom, boom, BOOM,

With a silk umbrella and the handle of a broom,

Boomlay, boomlay, boomlay, BOOM.

THEN I had religion, THEN I had a vision.

I could not turn from their revel in derision.

THEN I SAW THE CONGO, CREEPING THROUGH THE BLACK,

CUTTING THROUGH THE FOREST WITH A GOLDEN TRACK.

Then along that riverbank

A thousand miles

Tattooed cannibals danced in files;

Then I heard the boom of the blood-lust song

And a thigh-bone beating on a tin-pan gong.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

A roaring, epic, rag-time tune

From the mouth of the Congo

To the Mountains of the Moon.

Lindsay here captured the rock’n’roll aesthetic forty years before its invention. This wasn’t the same as the racist slander you found in the mouths of politicians of the time. This was praise, worship—primitivism, pure and simple.

In the same vein, the 1935 New York Herald Tribune article that made Leadbelly famous was headlined, LOMAX ARRIVES WITH LEADBELLY, NEGRO MINSTREL. SWEET SINGER OF THE SWAMPLANDS HERE TO DO A FEW TUNES BETWEEN HOMICIDES; Time magazine’s review was headlined MURDEROUS MINSTREL; Life magazine’s was headlined BAD NIGGER MAKES GOOD MINSTREL; and the Brooklyn Eagle referred to him as a VIRTUOSO OF KNIFE AND GUITAR. Upon Leadbelly’s return to the New York stage a year later, the Herald Tribune trumped itself with the following headline: AIN’T IT A PITY? BUT LEADBELLY JINGLES INTO CITY. EBON SHUFFLIN’ ANTHOLOGY OF SWAMPLAND FOLKSONG INHALES GIN, EXHALES RHYME.

It is true, of course, that without Leadbelly, who served as an archive of a long oral tradition in danger of disappearing, our shared musical heritage would be vastly poorer; he helped inspire not only the American folk movement of the ’50s (the Weavers’ massive hit “Goodnight Irene”) but the UK skiffle movement (Lonnie Donegan’s “Rock Island Line”). Later songs drawn from his repertoire include Ike and Tina Turner’s “Midnight Special,” Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Cotton Fields,” Led Zeppelin’s “Gallows Pole,” and Ram Jam’s “Black Betty.” But when Leadbelly was alive (he died in 1949), African Americans were creating much of the most sophisticated (i.e., complex, nonprimitive) music in the country, from blues to rhythm-and-blues to jazz. Unfortunately, certain whites of the period seem to have been more interested in celebrating what they considered the most primitive, elemental, and backward-looking African American musicians they could find. Apparently Leadbelly fit the bill perfectly.

One of those whites was John Lomax. Leadbelly had deep concerns over his relationship with the man, ranging from financial matters (Lomax and his son took two-thirds of Leadbelly’s income, rather than the fifteen percent mandated by New York law, and paid him an “allowance”) to being asked to wear prison garb for his performances rather than the suits and sharply creased shirts that he, like most professional musicians of the era, preferred. He even successfully sued Lomax for a greater share of his earnings. The great black American writer Richard Wright, who befriended Leadbelly, relied primarily on the latter’s account for a profile he wrote for the Daily Worker in 1937, in which he called John Lomax a “southern landlord,” and his touring of Leadbelly “one of the great cultural swindles in history.” The left-wing paper New Masses similarly reproached Lomax at the time of Leadbelly’s first performances, saying of him, “He embodies the slavemaster attitude intact.”

But Lomax was more of a showman than a slave master: as Robert Cantwell has written, “John Lomax belonged to a tradition of . . . the medicine-show mountebank of the rural south, with his blackface banjo player and miracle cure.” He presented Leadbelly as the very picture of authenticity and, in a paternal manner in keeping with that picture, kept Leadbelly away from more lucrative offers from people Lomax thought might exploit him.

Lomax’s conceptions of black Americans, however, weren’t that far removed from Vachel Lindsay’s. And they laid the foundation for the kind of primitivism Kurt Cobain celebrated.

JOHN AND ALAN LOMAX were indisputably the twentieth century’s leading collectors of what they called American folk music. As curators of the Library of Congress’s Archive of American Folk Song, they contributed immeasurably to this vitally important collection. Without their work, we’d have no “Home on the Range,” no “Midnight Special,” no Leadbelly, no conception of African American field hollers. Yet the assumptions that informed much of their invaluable work, particularly those of the elder Lomax, are questionable at best, and pernicious at worst.

In 1947, at the age of eighty, John Lomax published an autobiography, Adventures of a Ballad Hunter, and opened it with these words: “My family belonged to the upper crust of the ‘po’ white trash.’” Lomax effectively transformed this contradiction into an ability to get along with the high and low of American society. But his father, a slaveholder who had moved from Mississippi to East Texas in part because, as he said, “I did not want my family raised in contact with the negro [sic],” was more “white trash” than “upper crust.” And when it came to black Americans, John Lomax ended up sharing the values of both white classes.

In 1933, at the age of fifty-six, having spent much of his life studying cowboy ballads and other traditional white songs, John Lomax turned his attention to black music. His views had undergone few changes since the day, in 1904, when he attended a student concert at a Negro college and wrote disparagingly to his fiancée, “the old time negro [sic] trill is gone. These blacks are civilized . . . it is pitiful, pitiful.” Now he and his son Alan were to set out to record “the folk songs of the Negro—songs that, in musical phrasing and in poetic content, are most unlike those of the white race, the least contaminated by white influence or by modern Negro jazz.”

In order to eliminate this “white influence,” Lomax and his son Alan, according to John’s autobiography,

visited groups of Negroes living in remote communities, where the population was entirely black; also plantations where in number the Negroes greatly exceeded the whites, as in the Mississippi Delta. Another source for material was the lumber camp that employed only Negro foremen and Negro laborers.

However, our best field was the Southern penitentiaries. We went to all eleven of them and presented our plan to possibly 25,000 Negro convicts. . . . The Negro convicts do not eat or sleep in the same building with white prisoners. They are kept in entirely separate units; they even work separately in the fields. Thus a longtime Negro convict, guarded by Negro trusties, may spend many years with practically no chance of hearing the white man speak or sing. Such men slough off the white idiom they may have once employed in their speech and revert more and more to the idiom of the Negro common people.

John Lomax never explains why this “white influence” would be so undesirable. Instead, Lomax wanted to hear, as he wrote of a Houston party in 1932, the “weird, almost uncanny suggestion of turgid, slow-moving rivers in African jungles”; he wanted to feel “carried across to Africa . . . as if I were listening to the tom-toms of savage blacks.” In his autobiography, he comes right out and admits, “The simple directness and power of this primitive music, coupled with its descriptions of life where force and other elemental influences are dominating, impress me more deeply every time I hear it.” In other words, the music that was, for Lomax, the most authentic, the most black, the most free from “white influence,” was the most primitive.

Lomax seems to have been unaware that African music is far from primitive—its rhythmic sophistication is breathtaking—and that, in America, the white influence was necessarily pervasive, impossible to escape. In prison, he found what he wanted, yet it wasn’t the untainted music for which he longed. There, performers had been isolated from their sources for many years and inevitably sang garbled (and simplified) versions of songs of black, white, and mixed origin that they remembered from their days of freedom long ago rather than versions that emerged from actual practice in a community setting. Not only that, but these prisoners were almost all male, and thus an entire range of songs sung more often by women was completely overlooked.

The Lomaxes were not looking for the oldest songs—they were completely open to newly created songs in their narrowly construed “folk” tradition. Rather, they were looking for the songs that struck them as most essentially “genuine Negro folk songs.” In their application for a grant from the Carnegie Corporation, they wrote, “The Negro in the South is the target for such complex influences that it is hard to find genuine folk singing. . . . We propose to go where these influences are not yet dominant; where Negroes are almost entirely isolated from the whites, dependent upon the resources of their own group for amusement; where they are not only preserving a great body of traditional songs but also creating new songs in the same idiom.” Needless to say, they received the grant. And their quest for “the idiom of the Negro common people” resulted in a treasure trove of songs from both races—as performed by African Americans.

When John Lomax originally came up with the idea, back in 1910, of collecting black “folk” songs, he rightly saw it as a tremendously important project: the only people who had gathered them so far were white people who “dressed them up for literary purposes” or blacks who performed them in a far more sophisticated manner than that in which they were ordinarily sung. But by 1933, quite a bit of black music had already been recorded. Why did the Lomaxes completely ignore the recordings of traditional singers such as Henry Thomas and Mississippi John Hurt? For example, only a dozen of Hurt’s songs had been released. The Lomaxes could have tried to track him down and record more, but they preferred to track down their “genuine Negro folk songs” in places as removed as possible from the recording industry—Southern prisons. For in prison they literally had a captive audience, which made it far easier to persuade people to sing for them without remuneration. In addition, prisoners were without access to musical instruments, and the Lomaxes were far more fascinated by a cappella songs than accompanied ones, perhaps because the instruments blacks played were not African enough.

In this era, black prisoners were made to work, under whip and chain, from dawn to dusk; they were fed little better than dogs and were liable to be beaten. In the pages upon pages of his autobiography that John Lomax devotes to some of the worst prisons in the country, he expresses not a whit of horror or pity, not a hint of the degradation of the men he recorded. Although in 1933 he had written to the governor of Texas asking him to investigate the convictions of black prisoners and pardon those who “are only victims of misfortune,” in his autobiography he says not a word about wrongly convicted men, but gives examples mostly of murderers who acknowledged their guilt, quoting lines such as “Boss, I jes’ got to shootin’ niggers an’ I couldn’t stop,” as if marveling at the blacks’ propensity to kill. Lomax visited nearly every penal institution of the South, which could have given him the unique opportunity to write about the prison conditions there; but he covered the subject in the most cursory manner. Instead, he wrote approvingly, “A volume could be written about the reception given me by wardens of Southern penitentiaries.” And in their credulity-straining introduction to American Ballads and Folk Songs, the Lomaxes wrote, “The men were well fed and their sleeping quarters looked comfortable. . . . The visitors were given every freedom, and no case of cruelty was noted.”

Outside of the prisons, the elder Lomax continued to display a condescending attitude toward the black people he recorded, who were usually the more marginal members of society. One chapter of his autobiography, entitled “Alabama Red Land,” consists of nothing but droll tales told by and about poor blacks, reminiscent of Amos ’n’ Andy routines: “ ‘I heard that you’d been in jail for stealing a ham,’ I ventured. ‘Yassuh, I wuz in jail for stealin’ a ham, but I didn’t steal hit. I done told ’em dat if de feller what did steal hit would jes’ divide up, I wouldn’t mind stayin’ in jail a week for ha’f a ham. Jes’ so’s I can put my teeth in hit!’”

By the time Lomax brought Leadbelly to New York in 1935, Leadbelly had been working as Lomax’s servant for months, waking him up in the morning, fixing his coffee, shining his shoes, brushing his suit. Yet in the fall of 1934, Lomax wrote, “Leadbelly is a nigger to the core of his being. In addition he is a killer. He tells the truth only accidentally. . . . He is as sensual as a goat, and when he sings to me my spine tingles and sometimes tears come. Penitentiary wardens all tell me that I set no value on my life in using him as a traveling companion.” And when he arrived in New York, he introduced Leadbelly to reporters by telling them he “was a ‘natural,’ who had no idea of money, law, or ethics and who was possessed of virtually no restraint.” Needless to say, there was little truth to these remarks—Leadbelly was usually a soft-spoken, gentle man who was well aware that his drunken, frenzied murder attempts had been wrong; his understanding of money, law, and ethics was solid and strong.

Here’s how Lomax introduced Leadbelly to his New York audience: “Northern people hear Negroes playing and singing beautiful spirituals, which are too refined and are unlike the true southern spirituals. Or else they hear men and women on the stage and radio, burlesquing their own songs. Leadbelly doesn’t burlesque. He plays and sings with absolute sincerity. Whether or not it sounds foolish to you, he plays with absolute sincerity. I’ve heard his songs a hundred times, but I always get a thrill. To me his music is real music.” In other words, for John Lomax, Leadbelly was authenticity personified. Anything more sophisticated was “burlesque.”

KURT COBAIN first approached music as a fan. When he discovered a new band he loved he would become obsessive about them, wanting to absorb as much of their music as he could. Many of his attitudes came from observing how his musical heroes saw the world and wanting to emulate them. His relationship with bands like the Melvins and the Vaselines was nothing short of hero worship, and he would often write to members of bands he liked in friendship and admiration. When he became a successful performer himself he knew well how the fans felt about him, the demands they would make, and the emotional connection they had with him. He knew that above all, his fans expected him to keep it real and to not forget where he had come from.

Many of the performers Cobain admired were either deeply honest about themselves or politically idealistic. While he loved a wide variety of music, a large part of his ethics regarding the music business came from the punk movement, where bands prized sincerity over skill and saw the corporate nature of the business as an enemy. He was a purist in his approach to songwriting and based many songs on his own experiences. The fact that the life he was writing about was such a complex and, at times, disturbed one was what gave his songs their unnerving power. (Much of this can also be applied to Leadbelly, who sang with an unvarnished directness, wrote songs about his own experiences, and rebelled against his handlers.)

Cobain’s childhood was characterized by a series of disillusionments: his parents split up when he was seven, his father broke a promise to not get a new girlfriend, and it became impossible to live with his mother’s new boyfriend. He was passed around to different family members and friends, never settling anywhere for long; for periods in his teens he was effectively homeless. As he absorbed the ethics of punk from his heroes and contemporaries, a very personal anger infused his outlook. But one can also feel something else behind this: the hollow feeling of the little kid in “Sliver” who is left with his grandparents while his parents go to a show and who wants his grandma to take him home, or the terrible sorrow of the same boy ten years later, in his early teens, who can’t be taken home because he doesn’t really have one anymore; in other words, the feeling that people just shouldn’t let you down.

Many young punk fans found echoes of their personal frustrations in punk’s commands to keep it real, make it raw, do it yourself, and be against everything. Cobain wanted to be authentic partially because the seventeen-year-old fan he had once been would have wanted him to be authentic; he didn’t want to let himself down, and he didn’t want to let the average seventeen-year-old punk rock kid down. But at the same time he also felt that letting everyone down was inevitable.

BY ALMOST ANY standards, Kurt Cobain’s version of “In the Pines” seems “authentic.” There doesn’t appear to be anything “fake” here: the song is traditional, the passion is real. The subject matter fits closely with his preoccupations, and the dark woods of the chorus must have reminded him of the forested landscape of his small-town home in Washington State. But why did he perform Leadbelly’s version of “In the Pines” instead of anyone else’s? Like Lomax, did Cobain also consider Leadbelly’s music “real music”? No doubt. Was he looking for the same thing that John Lomax was looking for? Not exactly.

Lomax had been searching for the most authentic Negro songs he could find, and he believed that Leadbelly had unearthed some of them, in part because of his exposure to prisoners who had been out of circulation for decades. But Leadbelly’s repertoire was replete with songs of purely Anglo-American origin. He once recalled, “I learned by listening to other singers once in a while off phonograph records. . . . I used to look at the sheet music and learn the words of a few popular songs.” Lomax himself admitted, “For his programs Lead Belly always wished to include [Gene Autry’s] ‘That Silver-Haired Daddy of Mine’ or jazz tunes such as ‘I’m in Love with You, Baby.’ . . . We held him to the singing of the music that first attracted us to him.” And during his performances, Lomax would direct Leadbelly as to which songs he should sing.

Lomax’s idea was to trace African American musical culture to its source, its roots, on the Darwinian assumption that those roots were less complicated, less corrupted, more “pure,” than the songs of his day (again, he was wrong). He was looking for cultural authenticity, a relatively unadulterated version of a particular musical culture (in this case African American).

Cobain was also searching for something “authentic” and pure, but he wasn’t necessarily looking for the roots of American music. He was in quest of personal authenticity, “keeping it real,” singing about his own, personal pain, his own idiosyncratic vision. Cobain called Leadbelly his favorite performer because, for one thing, Leadbelly had by now become as mythical as Paul Bunyan, an ideal representative of a purer music that somehow predated the introduction of artifice into popular culture. But Leadbelly also symbolized something elemental, resonant, and mysterious, something akin to the mystery and violence Cobain saw in his own soul. Doubtless, if John Lomax had not presented Leadbelly as the embodiment of the primitive, savage, black killer who sings age-old songs in the most sensual manner conceivable, Leadbelly would have held far less attraction for Cobain.

Much of Leadbelly’s appeal, not to mention his fortune and fame, both when he was alive and after his death, derived from a racist view that the most authentic black culture was also the most primitive. Over time, this view lost much of its racial tinge: now it is commonly accepted by rock fans the world over that the most authentic music is the most savage and raw. Of the many varieties of self-expression, it is the most primitive that rock fans associate with the greatest emotional honesty. (Contrast this to Schubert and Mahler, who conveyed emotional intensity in their songs by the interplay of major and minor modes.) So for Cobain, as for most rock stars and fans today, real rock’n’roll must be shackled to the kind of primitivism that accompanied Leadbelly’s career, an idealization of “savage” simplicity. If Cobain had broadcast the facts of his own painful life in the wordy, sophisticated tradition of Loudon Wainwright III rather than the bare-bones tradition of Leadbelly, he would have been a role model for next to nobody.

And this bare-bones tradition extends beyond the artist to the medium itself. We have already mentioned representational authenticity, by which we mean simply that something is what it claims to be and not a counterfeit. Clearly, MTV Unplugged fails this simple test: for it to be unplugged, we’d have to unplug our TVs. But on a less basic level, by presenting artists in a more-or-less “acoustic” environment, the program pretends to show us the most “authentic” aspects of the performer. Because the recording of music gives such scope for faking of various kinds, it has become a real question whether or not the artists we listen to are really what they claim to be. Are they really playing their instruments? Can they really sing like that? But such questions of authenticity rarely tell the whole story, and they have often been elided with questions of personal and cultural authenticity. For instance, in MTV Unplugged, the stripped-down format ensures that we see the artist perform without adulteration. However, this constriction is then used to reinforce the notion that this performance is authentic in some deeper way.

COBAIN’S DEATH created a problem for grunge. The meaning of the term had already shifted from referring to a small number of bands from the Seattle area to embodying the entire fashion and musical scene that developed around the success of Nirvana and their contemporaries. But at all times it was defined by being honest, gritty, and down-to-earth (not to mention loud). Nirvana’s guitar-based simplicity and rawness of emotion, combined with Cobain’s punk ethics and apparent loathing of the music business, made them the ultimate authentic band of their era.

What individuals understand by the word authentic tends to be influenced by what exactly they perceive as fake, in a pejorative sense; seeing something as authentic is thus often a moral judgment as well as an aesthetic one. Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols once sang “We mean it, man” about having “no future,” but he was still alive; when Cobain killed himself, he proved that he really had meant it. In his suicide note, aimed at his fans, which his wife Courtney Love broadcast in public with her own angry interjections, he said, “The fact is, I can’t fool you, any one of you. It simply isn’t fair to you or me. The worst crime I can think of would be to rip people off by faking it and pretending as if I’m having 100% fun.”

The desperately sad and frustrating thing is that the only way he could see of being true to himself was being true to the person that his fans wanted him to be, the person he had once wanted to become. Having spent so long wanting to be that person, it must have been extremely hard to realize that, having succeeded at last, he no longer wanted the same thing. We may think that he would have been equally true to himself if he had made a different decision: giving up playing live, breaking up the band and carrying through with the sessions he had booked with Michael Stipe, taking a break from music altogether, or whatever. But he was suicidally depressed, and all he could see were insurmountable obstacles.

While his self-loathing and personal suffering had given the music an edge of angst that fans, especially adolescents, could identify with, his suicide raised the stakes too high. Rival musicians and peers wallowed in the reflected tragedy of his death. Eddie Vedder’s band Pearl Jam had recently overtaken Nirvana as the best-selling rock band in the United States; in an interview soon afterward, Vedder said, “I always thought I’d go first. I don’t know why I thought that . . . it just seemed like I would. I mean, I didn’t know him on a daily basis—far from it. But, in a way, I don’t even feel right being here without him.” Vedder made this self-righteous speech in spite of Cobain’s well-documented disdain for Pearl Jam. And in the same interview, Vedder attacked the media for doubting his own authenticity, which he linked to that of Cobain: “They don’t know what’s real and what isn’t. And when someone comes along who’s trying to be real, they don’t know the fuckin’ difference.”

As one looks back through other interviews given by other rock stars after Cobain’s death, it often seems as though they too were feebly saying, “Look at me, look at me, I feel pain too.” Perhaps it is unfair to criticize—it was impossible to come up with the words to express the sadness that so many shared, and they were only fumbling for the right thing to say. But no one was willing to match Cobain’s final gesture, and all other grunge music was robbed of its essential gravity. Suddenly it looked like the other bands were just playing a part, whereas Cobain had been for real. Grunge started to ebb into the grunge lite of Bush and the Stone Temple Pilots; bands like Green Day added a dash of angst to their punk-pop and moved into the same territory; and in general, no post-Nirvana guitar-based band, whether postgrunge, mainstream, or even metal, could ignore the pressure to create autobiographical songs about their misery. Nirvana looked more and more like the only “real” band in history—a one-time phenomenon that had grown out of its extraordinary singer.

And as fans of the music, we ended up with the same guilty, voyeuristic unease that was provoked by Richie Edwards of the Manic Street Preachers hacking “4 Real” into his arm for a photo shoot. The guitarist in the original band’s line-up, Edwards’s punk sensibilities had driven its early puritanical agenda and public manifestos. His public act of cutting himself had done much to gain the band notoriety. The intensity of his desire to live up to the image he had created and to not sell out was in the end unsustainable, and he disappeared in February 1995 as the band was about to leave for an American tour. His abandoned car and credit card transactions gave some faint hope that he had vanished for only a time, but he is generally presumed dead.

Just like the white fans of Leadbelly and the folk fans who rediscovered blues singers in the 1960s, fans demanded that their heros be real, something more than mere entertainers. Cobain and Edwards took this demand seriously, so seriously that they laid their deepest personal problems out for all to see. They allowed us to wallow in their misery. They proved to us that they were the genuine article, and, in the act of proving it, they ultimately destroyed themselves. And they did it because we were watching.

We might wish that Kurt Cobain had calmed down and grown old, made mellow, grown-up records with Michael Stipe, maybe even given up the band and retired to a farm somewhere. We might wish that Richie Edwards had just moved to a beach hut in Australia and left all his problems behind. But it’s too late.

It’s too simplistic to say that it is our fault, but deep down we wonder: if we had not encouraged them—if we had thought less of “authenticity” and more simply of good music—might they have survived? This weird complicity between audience and performer can create great songs and great rock stars. But it also sometimes kills them.