The Will Rogers Museum, Claremore, Oklahoma

CHAPTER THREE

T.B.

BLUES

The Story of

Autobiographical Song

San Antonio, January 31, 1931

When Jimmie Rodgers sang “T.B. Blues,” his audiences knew that he meant it—and that was one of the things, amid all the hillbilly hokum of the day, that distinguished him from the likes of Vernon Dalhart and Carson Robison. It is what country music fans mean today when they bestow their highest accolade on an artist by calling him “sincere.”

NOLAN PORTERFIELD, Jimmie Rodgers

BY 1931, JIMMIE RODGERS was probably the most famous musician in the country. He wasn’t a very inventive guitar player or singer; he couldn’t compose new songs very well, almost always enlisting considerable help; he was short, almost completely bald, and in very poor health; his musical trademark was a rather gimmicky yodel—in short, he would seem, to our eyes, to have had little to recommend him. Yet he inspired the same kind of frenzy as Sinatra and Elvis would years later.

For Jimmie Rodgers personified a particular type of American hero. He had been a hardworking man—a brakeman on railroad lines—but he had also traveled and roamed, living the peripatetic life. There was a romance about him that was easy to make into myth—the myth of the rambling man, who goes from town to town and from girl to girl, always heeding the call to wander on, but nonetheless misses his Mississippi home and the sweet woman he left behind. Jimmie Rodgers vicariously gave his listeners the freedom they envied while affirming the comforts and values of their quotidian lives.

But it wasn’t only that. Jimmie Rodgers sang the blues. He sang them honestly and without affectation, making them his own without imitating anyone else, and imbuing them with what we can only call “personal authenticity”—the feeling that they were made out of his own tears and laughter, his own memories and dreams, his own life and everything in it. Of course, things weren’t that simple, but somehow he convinced everyone that they were.

By 1931, though, after three years of unprecedented fame, there was one major aspect of his life that Jimmie Rodgers had not yet sung about or even spoken about in public: his health. Other aspects of his life he’d dealt with in his customary breezy manner, never getting too specific or delving too deeply, either maintaining a studied nonchalance or indulging in sentimental simplification. But now he was going to give his public a dose of reality—he was going to sing about the disease that was killing him by degrees, a disease that many of his fans already knew he had.

Nolan Porterfield, whose biography of Jimmie Rodgers is nothing less than a masterpiece, has written,

Mention a song called “T.B. Blues” today, and most people give you a brief look of disbelief, followed by sniggers and curious shakes of the head. Boy, what those oldtime hillbillies couldn’t think of! The notion of a prominent entertainer singing about the disease that was killing him . . . strikes them as a rather literal (and pathetic) sick joke, on the macabre order of, say, Nat King Cole huskily warbling some merry ditty about lung cancer.

But tuberculosis was no stranger to Jimmie Rodgers’s listeners. For decades it had been the leading cause of death in the United States, and it had killed 3.5 million Americans between 1900 and 1925. At the turn of the century up to ninety percent of American adults had had tuberculosis at one time. Nor was it that uncommon to sing about sickness—a different “T-B Blues” had been a hit for blues star Victoria Spivey in 1927 (and had been covered by Willie Jackson as well; Spivey recorded a follow-up, “Dirty T.B. Blues,” two years later), Bessie Tucker had recorded a “T.B. Moan” in 1929, and others had also sung blues songs about illnesses. The lyrics to Rodgers’s “T.B. Blues” were mostly adapted from previous blues lyrics—there was nothing essentially new here.

Except for one thing. Previously, when singers had sung about having tuberculosis—or for that matter, about being lovesick, or having the blues, or missing their home—they may not have been singing about themselves. Victoria Spivey, for instance, did not have tuberculosis. Songs about illness were typically as full of generalities as a love song (“Oh now, the T.B.’s killin’ me—I want my body buried in the deep blue sea,” Spivey sang); few of them divulged intimate details. Blind Lemon Jefferson’s “Pneumonia Blues” blames his condition on “slippin’ ’round the corners, running up alleys too, watching my woman trying to see what she goin’ do,” which is clearly fiction. Lonnie Johnson saw fit to sing about a shipwreck he was on but not about the flu epidemic that killed almost his entire family; like most blues singers, he was not given to writing songs about his personal life. But in Jimmie Rodgers’s case, his listeners either knew or quickly inferred that he was singing about his own illness. This lent the song an authenticity that Spivey’s had not possessed.

At the same session, Rodgers sang another song he’d recently cowritten, “Jimmie the Kid.” It’s not one of his greatest songs. In it, he gives some not very interesting facts about his life, including naming a number of the train lines he’d traveled on, and he couches the whole in the third person. But it’s unusual in one important respect: it is, in its way, an autobiography. It doesn’t include just a detail or two—it’s his entire life story.

These are autobiographical songs: songs that are truly about the singer (or writer) more than about anything else, that tell the truth, and that refrain from bleaching out facts through generalization. For example, Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman” doesn’t quite qualify as autobiographical—although Sledge wrote it about his own experience, he bleached out all specifics so that the song could apply to anyone. On the other hand, “The Ballad of John and Yoko” is a sterling example of autobiographical song.

Taken together, “T.B. Blues” and “Jimmie the Kid” represent a fascinating moment—a crystallization of sorts—in the development of personal authenticity in popular music. At the time, there was no good reason to think that the person singing on a particular record was really who he or she appeared to be: records were disembodied voices, not real people, and those voices could—and usually did—sing fiction. Public performances were likewise entertainments that had little if anything to do with the personal experiences of the entertainer. By singing about his own life in a way that audiences could call truthful, Rodgers was, intentionally or not, vouchsafing that he was as genuine as the record they were holding.

Today, after decades of music partially defined by ideas of sincerity, this may not seem very unusual. We have become accustomed over the last forty years to hearing autobiographical songs, ranging from Loretta Lynn’s “Coal Miner’s Daughter” to Nirvana’s “Pennyroyal Tea” to Usher’s “Confessions Part II.” Performers often use autobiographical song now as a talisman of their personal authenticity, parading their insecurities and problems through song in order to boast of how “real” they are. But it was not common to give such detail in song until relatively recently, especially not in songs aimed at a mass market.

LET’S LOOK AT an example that parallels “T.B. Blues.” In the entire history of American popular music, why have so few blind singers sung about being blind? Sleepy John Estes recorded “Stone Blind Blues” in 1947, and Sonny Terry recorded “I Woke Up One Morning and I Could Hardly See” in 1962. But besides these two songs, the only other instances seem to be a couple of gospel songs by Blind Gary Davis and Blind Roger Hays, and a wordless composition by jazz multi-instrumentalist Rahsaan Roland Kirk.

Of course, there have been plenty of brilliant blind songwriters, ranging from pioneer bluesmen Blind Lemon Jefferson and Blind Willie McTell to more recent artists such as Stevie Wonder. In fact, one scholar has counted no fewer than thirty-two blind prewar blues and gospel singers. Few of these artists have been reluctant to sing in the first person or to tell stories in their songs. But there is one subject they almost all avoid, the one that is absolutely central to their identities. Why?

You see, the reason blind singers rarely sang about being blind is simple: there was no audience for such a song. Who could relate to it? The number of blind listeners was undoubtedly far fewer than the number of listeners who’d been jilted by a lover.

This desire to “relate” to a song is essential for understanding the meaning of the blues—and “T.B. Blues” is a blues.

BLUES IS SAID to be a very personal music. There’s certainly some truth to this view—blues songs of the first half of the twentieth century were generally more personal than other songs, and early autobiographical songs were almost always blues or blues-related. Yet it would be a mistake to view the blues as primarily either a confessional mode or a kind of collective autobiography of black Americans, two views that seem prevalent today.

For early blues, like early cowboy songs, were mainly about a certain set of people, mostly black but sometimes white (like Jimmie Rodgers), both male and female, who lived largely itinerant lives, traveled from town to town, job to job, partner to partner; a people who thought far less of morality than of enjoyment; a people given to sex, violence, and hard liquor; a people inured to poverty and injustice, and expecting little else. Blues songs were generally not about hard-working and sober laborers, church-going women, homeowners, young men attending vocational school, soldiers, sailors, or civil servants. Instead they focused on social outcasts.

Naturally enough, many blues singers were themselves social outcasts—respectable folks wanted to have nothing to do with them. And social outcasts have nothing to lose. Far less invested in their reputations than their peers are, they can afford to be forthcoming about their sins, hard times, and sensual joys. Blues thus lends itself very well to gritty first-person narrative, narrative that purports to be autobiographical. And the large majority of blues songs fit this mold.

But those narratives usually either were fiction (Blind Willie McTell’s “Writing Paper Blues” is one of the best storytelling blues songs ever, but McTell couldn’t write), were too vague to be strictly personal, or concerned an event in which the singer was only a peripheral figure (Charley Patton’s “High Water Everywhere” concerns a flood, Lonnie Johnson’s “Life Saver Blues” a shipwreck). Autobiography certainly wasn’t out of the question, but it was relatively rare: I would estimate that only about one to three percent of prewar blues songs could be called autobiographical. And few blues songs really tell compelling stories—most of them are so unrevealing as to be opaque.

Interestingly, most prewar autobiographical blues songs deal with prison experiences or run-ins with the law, perhaps because this subject matter naturally lends itself to specificity. But blues songs tended to be about situations to which listeners could relate, rather than situations peculiar to the singer.

The songs blues singers wrote specifically about themselves tend to stand out because of their uncommonness. In 1930 Charlie Jackson sang a compelling account of performing at a dance and being arrested and jailed; apparently it was so unusual to write autobiography that the song was entitled “Self Experience.” And in 1940 Booker White, prompted by a recording director who was dissatisfied with the repertoire of standards he had brought to the studio, composed on the spot a handful of autobiographical songs such as “Parchman Farm Blues,” “When Can I Change My Clothes,” and “District Attorney Blues,” suggesting that White didn’t commonly perform material of this nature.

Another autobiographical blues song provides perhaps the closest contemporary parallel to “T.B. Blues.” The Memphis Jug Band’s 1930 “Meningitis Blues,” written and sung by Memphis Minnie, is not only a moving and very personal account of a near-fatal illness, it tells a truly autobiographical story—which she seemed to acknowledge when she rerecorded it a few days later as “Memphis Minnie-Jitis Blues.” It begins with an extraordinarily personal verse: “I come in home one Saturday night, pull off my clothes and I lie down; and that mornin’ just about the break of day that meningitis began to creep around.” It is as if she were pulling the listener right into her life—and her suffering. Spelling out all the details, she describes her pain, how her companion took her to the doctor and then to the hospital, and how the doctors gave up on her.

Memphis Minnie’s accomplishments are plentiful: she was an extraordinarily skilled songwriter (she wrote Led Zeppelin’s “When the Levee Breaks” and Chuck Berry’s “I Wanna Be Your Driver”), an ingenious guitarist, a fine singer, and an astute businesswoman. Although she was just as rough and rowdy as her male counterparts, her recordings emphasize sexual satisfaction, domestic banter, and mellow good times, rather than the gratuitous violence expressed by many of her predecessors. And perhaps this explains why she was a huge star in the 1930s, during which she continued to record the occasional autobiographical song.

She was soon joined by fellow Memphian Sleepy John Estes, who began to sing songs about his lawyer, his blindness, and other personal matters. Robert Johnson’s “Crossroads Blues” gives every indication of being about his own experience, although Johnson hid more than he revealed; the mystery he created with his seemingly autobiographical but actually remarkably opaque songs left thousands of fans and researchers Searching for Robert Johnson, as one book title has it.

As for Lightnin’ Hopkins, who began recording in 1946, one gets the feeling that the reason he turned to autobiography was that he couldn’t actually remember other people’s songs very well (with the exception of those of his mentor, Blind Lemon Jefferson). His songs usually weren’t well thought out like Johnson’s, Memphis Minnie’s, or Rodgers’s—they were extemporized on the spot, just strings of made-up and free-associated verses, rarely hanging together or completing a picture. As Francis Davis puts it, “Practically anything you’d ever want to know about [Hopkins], no matter how trivial, is in a song somewhere. . . . In general, [he] was the least bardic of the great blues singers: less interested in telling a story than setting a mood and speaking whatever happened to be on his mind the second the tapes started to roll.”

Since blues songs purport to be autobiographical, it would only make sense if occasionally singers sang directly about their lives. Yet as most of these examples attest in their own ways, autobiography was more the exception than the rule.

WHAT ELSE DID people sing about in this era if so few of them sang about themselves? Most of them sang songs they learned from others: from Tin Pan Alley, from fellow musicians, from family. If you wanted to write your own song, you might have taken Woody Guthrie’s advice from his 1943 memoir, Bound for Glory: “If you think of something new to say, if a cyclone comes, or a flood wrecks the country, or a bus load of school children freeze to death along the road, if a big ship goes down, and an airplane falls in your neighborhood, an outlaw shoots it out with the deputies, or the working people go out to win a war, yes, you’ll find a train load of things you can set down and make up a song about.” Or you might have written a love song, or a sentimental parlor ballad. But it probably would never have occurred to you to write a song strictly about your own experiences.

It’s certainly possible that a few of the hundreds of nineteenth- and very early twentieth-century cowboy, frontier, and sailor ballads may have been autobiographical when they were first written: “The Old Chisholm Trail,” “The State of Arkansaw,” “The Buffalo Skinners,” “The Ballad of the Erie Canal,” and so on. Unfortunately, we know nothing about who wrote them. The same goes for even older first-person ballads.

By the twentieth century, hillbilly or old-time music generally was far less autobiographical than blues. It stuck much closer to established traditions, and the subject matter of the songs reflected this. But occasionally a singer might inject autobiographical detail into a song. Uncle Dave Macon, the first star of the Grand Ole Opry, made a frequent practice of spoken interludes interjected between, before, or in the middle of his tunes. His 1928 “From Earth to Heaven” is a fascinating example: he begins by giving the name and address of his wagoning firm, then sings about his daily routine. But then he claims to have sworn off drinking and dedicated his life to God, neither of which he actually did. (He also disparages the motorcar since it ruined his wagoning career; but at the same session he sang a paean to “The New Ford Car.”) The means may be autobiographical, but the aim of “From Earth to Heaven” is spiritual, and the song, which begins with the truth, ends with fiction.

Besides Macon and Rodgers, perhaps the only other hillbilly singer who sang anything approaching autobiography was Goebel Reeves. Reeves was one of dozens of yodeling singer-songwriters following Jimmie Rodgers’s path, among them Jimmie Davis, Cliff Carlisle, and Gene Autry. Calling himself “The Texas Drifter,” he recorded “The Texas Drifter’s Warning” in January 1930. A well-educated Texan from a wealthy family, Reeves had chosen the life of a hobo not out of necessity but because of its romantic appeal. In his “Warning,” he sings of how he ran into a cop in West Texas who took all his money and then got a job picking cotton for next to nothing. Reeves was an excellent yodeler and had once played with Rodgers. But his songs and singing were far more studied, with little of Rodgers’s charm. “The Texas Drifter’s Warning” may well be autobiographical, though Reeves was prone to embellishing facts. If anything, it’s surprising that there weren’t more such songs in this period. After all, ever since he began having hit records in 1927, Jimmie Rodgers had made the central pretense of the blues—first-person narrative centering on the performer’s own experience—into an important pretense of hillbilly music too. Before him, it simply hadn’t been that way.

FROM VERY EARLY in his life, Jimmie Rodgers had wanted to be a musical entertainer. Every chance he got, he’d take out his guitar and sing for anyone who’d listen. As a business, though, that kind of playing was worse than nothing at all. No aficionado of traditional mountain or “old-time” music, Jimmie specialized in Tin Pan Alley hits, minstrel numbers, or other songs popular among city folk. But in order to earn a living, he spent most of his time working on the railroad, traveling throughout the South, where he was exposed to all sorts of music, often playing with and for African Americans.

He auditioned for Ralph Peer of the Victor Talking Machine Company in 1927 in Bristol, Tennessee, and recorded a couple of unremarkable songs. A few months later, he traveled to New York, gave Peer a phone call, and pretended that he just happened to be in town and had a little time to record a few more sides. The session, held in Camden, New Jersey, was not at first a success: Peer was looking for either original or traditional but forgotten material that he could copyright, and all Rodgers could perform were other people’s songs.

Finally, he relaxed enough to perform a ditty whose opening lines were, “T for Texas, T for Tennessee; T for Texas, T for Tennessee; T for Thelma—the gal that made a wreck out of me.” Peer was unimpressed, but released the song anyway under the title “Blue Yodel,” since Rodgers yodeled after each verse. Perhaps because it was a blues with a gimmick, the song was an enormous hit that catapulted Rodgers to unprecedented fame. Hit followed hit, and Jimmie Rodgers quickly became a household name, his appearances, particularly in the South, creating a sensation.

Besides his “blue yodels” (he recorded thirteen), Rodgers hardly wrote any of his material by himself. Between 1928 and 1930, his most frequent collaborator was his sister-in-law, Elsie McWilliams, but he obtained songs from a variety of other sources, too. If he had been left to his own devices, he may not have written a single song. He was happier, it seems, performing other people’s material.

But he hadn’t reckoned on being tied to a businessman as astute and farsighted as Ralph Peer.

IS IT A coincidence that the first black vocal blues hit record, the first hillbilly hit record, and the first records by the artists who would define modern country music (Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family) were all recorded by the same man? Was Ralph Peer truly an American visionary, or did he stumble onto all this more or less by accident? Or was he simply a brilliant businessman?

Here are the facts. Peer was born in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1892, the son of a music dealer. As a teenager, he began working with Columbia Records, but by 1920 he had become the assistant to Fred Hager, the recording director of the OKeh label. In February of that year, a twenty-six-year-old black pianist, songwriter, and music publisher named Perry Bradford convinced OKeh’s president to allow Mamie Smith, a black female singer, to record a song he’d written—even though Hager advised against it, fearing a boycott against any label that broke the color bar. “Crazy Blues,” backed by a black band Perry had organized called the Jazz Hounds, was the first blues record sung and played by blacks. And, in part because of Peer’s promotional efforts, it was a huge success.

Three years later, an Atlanta record dealer named Polk Brockman saw a newsreel at the Palace Theater in Times Square of a Virginia fiddler’s convention; Brockman called OKeh Records and asked them to come down to Atlanta to attempt a few recordings. So in June 1923, Peer conducted the first commercial location recording with portable equipment (recording both black and white performers). One record made at that session, Fiddlin’ John Carson’s “The Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane” coupled with “The Old Hen Cackled and the Rooster’s Going to Crow,” was the first country music hit (although the genre wouldn’t be called country for a number of years). It sold so rapidly in Atlanta that Peer started making frequent trips to the South (as did the representatives of other record companies).

But late in 1925, Peer and OKeh had a falling out, and Peer left to pursue other business, without success. In 1927, down on his luck, Peer contacted the Victor Talking Machine Company with a brilliant idea. As he later wrote, “The arrangement was that I would select the artists and material and supervise the hillbilly recordings for Victor. My publishing firm would own the copyrights, and thus I would be compensated by the royalties resulting from the compositions which I would select for recording purposes.” In return, he would work for Victor for nothing—a nominal salary of $1 per year.

From then on, Peer was on a quest for new songs. They could be old, traditional songs—as old as the hills—so long as they had never before been recorded or published as sheet music. Or they could be new, or purloined. No matter—what was important was that Peer could have them copyrighted in the artist’s name. The agreement he made with the artists he recorded made him the publisher and therefore assignee of the copyright of each new song, without any initial outlay on his part. In return, he arranged for the artists to record these new songs, and advanced them money on the royalties.

Peer was completely uninterested in songs whose provenance was known and established, for he himself could make no money on these. If his artists recorded previously copyrighted or public domain songs, they would only stand to make $50 per side (at best)—Victor’s standard fee (which was far higher than that of other record companies)—and he would make nothing. He later recalled that “Jimmie would bring in some famous old minstrel song and just do it word-for-word, and of course I’d stop that immediately. I’d say, ‘You didn’t compose that.’”

With the songwriting royalties that Peer guaranteed his artists for original songs, they could make a half cent per record—not bad if you released twenty or thirty sides a year and each disc sold thousands of copies. Peer, as publisher, made three times that amount—about a million dollars a year—and generously loaned some of his cash to his favored artists.

So that’s why Peer pushed Jimmie Rodgers into recording original numbers almost exclusively, most of them cocomposed by Rodgers himself, thus spurring Rodgers to constantly come up with new topics for songs. Eventually one of those topics would turn out to be his own life.

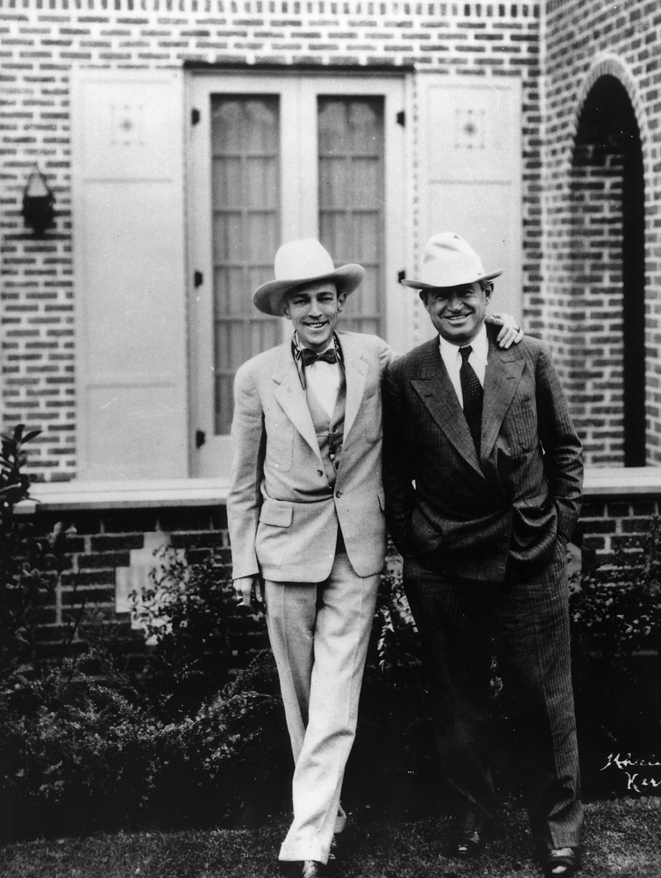

JIMMIE RODGERS arrived in San Antonio fresh off a brief but intense benefit tour for victims of drought and the Depression, a tour headlined by Will Rogers, an entertainer Jimmie Rodgers idolized. Jimmie Rodgers’s change in direction on January 31, 1931—his recording of material that was more autobiographical than anything he’d attempted before—may have resulted from his close contact with America’s most popular entertainer.

When I say “most popular,” I don’t just mean that Will Rogers was the most popular entertainer of his day—there’s no doubt of that. I mean the most popular American entertainer ever. His best biographer, Ben Yagoda, claims as a “fact” that Rogers “was loved more than any American has been loved before or since,” and the claim appears entirely plausible. When he died in a plane crash in 1935, Yagoda writes,

the magnitude of the reaction, in point of fact, was such as you would expect the passing of a beloved President to engender. Will Rogers, fifty-five years old, had a radio show, wrote a daily newspaper column, acted in the movies. Years earlier he had been a rope-twirling monologist in the Ziegfeld Follies, before that a vaudeville gypsy. Yet people had come to depend on his presence—his absence was making them realize—more than that of any politician.

One of the keys to Will Rogers’s popularity was undoubtedly the sense his audiences got that he was being “authentic,” being himself. When he first appeared in vaudeville in 1911, he “was like nothing else on the vaudeville stage.” Where other monologists told humorous stories in “carefully constructed personas,” Will Rogers, “self-effacing and understated, was always himself, or something very close to it. . . . His remarks appeared insistently extemporaneous, almost improvisational.” (In this, he was following an old American tradition, joining Davey Crockett, Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, Buffalo Bill Cody, and many others.)

And being himself included being autobiographical. In fact, back in 1921, Will Rogers had made what is most likely the very first film that portrayed the life of its maker, One Day in 365 (whose working title was No Story at All), which is a bit like an episode of The Osbournes. As Yagoda describes it,

Not only did Will star in it and write the script but the cast was his own family and the only set was his own house. The script (no complete print survives) [describes] a day in the life of the Rogers family. Will desperately tries to find a suitable scenario for a picture due to start shooting that day, but he is constantly interrupted. . . . By 1:30 in the morning, there’s still no script; in a final close-up, Will speaks into the camera. “Some of these days I’m going to put on a story from real life—but then no one would believe it.”

By the time Jimmie Rodgers appeared onstage with Will Rogers, the latter was also the most widely read columnist in the country, with his daily columns appearing in more than four hundred newspapers. Once again, he wrote whatever came off the top of his head, never bothering to construct a persona any different from who he was. The same held for the talking films he made in the early 1930s, which were more popular than those of any other actor. He didn’t act in these films—he improvised and behaved naturally. That he was aware of the difference between himself and others in this respect seems borne out by the name of the imaginary political party he invented when Life magazine had him pretend to run for president in 1928: Anti-Bunk.

Nobody in the 1920s or 1930s, then, embodied personal authenticity better than Will Rogers. And that was bound to rub off on the man whose career was beginning to depend on precisely that same quality.

BILL MALONE has written of Jimmie Rodgers, “If he sang ‘I’ve Ranged, I’ve Roamed, and I’ve Traveled,’ his listeners were sure he had done just that. When he sang ‘Lullaby Yodel,’ many people were convinced that he was singing to an estranged wife who had taken their child with her (even though his wife’s sister wrote the song!). ‘High Powered Mamma,’ of course, just had to be about that same wife who ‘just wouldn’t leave other daddies alone.’”

Indeed, there was some basis for this belief. Many of his sentimental songs, largely written by McWilliams, were based on elements of his personal history, though in a decidedly vague way: “My Little Old Home Down in New Orleans,” “Daddy and Home,” “My Rough and Rowdy Ways.” And he sang them with a heartfelt delivery that made them seem to describe not only his own life, but that of his listeners too. As Porterfield explains, “To many, Jimmie Rodgers made ‘sincerity,’ ‘honesty,’ and ‘heart’ the compelling forces of country music.”

Jimmie Rodgers was the first celebrity singer whose songs, one and all, were widely taken to be about his own life. And that became the modus operandi of several generations of country singers—Woody Guthrie, Hank Williams, Loretta Lynn, Dolly Parton, Merle Haggard, and many others. But Rodgers didn’t start out being autobiographical: it was only after he became a celebrity that he started singing about his battle with tuberculosis, for it was only then that his audience knew enough about him to care about his personal problems.

Let’s put it another way. Jimmie Rodgers started out just like any blues musician: singing songs about wild women and rambling men, fast trains and lonely nights. But at a certain point he might have reflected upon the facts of his celebrity. His listeners all thought he was singing about his own life, even when he sang other people’s songs, even when he sang about imaginary situations and unfamiliar places and women he’d never met. Why not, then, actually do what they already thought he was doing? Why not actually sing about dying? Couldn’t he then take his listeners to a new level? They were buying his records, after all, not just because they liked his music, but because they wanted to learn more about him. So why not sing about the most important fact of his life?

One reason so few blind singers ever sang about being blind is precisely this: no blind singer ever had a following like Jimmie Rodgers’s. No blind singer was ever confronted with millions of fans telling him that the reason they bought his records was that they believed he was singing about his own life and they could relate to him. But Jimmie Rodgers was. And that may be why he decided to record two songs about his own life on that January day in 1931.

JIMMIE RODGERS left the tour he was on (with Will Rogers) in Dallas, having learned that Peer was on his way to San Antonio with portable recording equipment. Probably Peer had planned his trip primarily to record Rodgers, but hoped to find some other local talent as well. Rodgers had a day or two to rest and prepare for the session, while Peer lined up some local musicians to accompany him.

The sessions were held at the Texas Hotel, and for the first number, “T.B. Blues,” Jimmie was accompanied by an excellent local steel guitarist, Charles Kama. He opened the song with a line that could have come from any number of songs: “My good gal’s trying to make a fool out of me.” But what followed exemplified Rodgers’s ingenious mix of humor and tragedy: “Trying to make me believe I ain’t got that ol’ T.B.” From there, the song became increasingly morbid, ending with the couplet

Gee, but the graveyard is a lonesome place.

They put you on your back, throw that mud down in your face.

Perhaps to signify that this wasn’t one of his usual novelty numbers, Rodgers uncharacteristically refrained from yodeling on this song, instead singing the chorus, “I’ve got the T.B. blues,” in a yodeling manner.

A year or two earlier, Jimmie Rodgers had written to one of his correspondents and collaborators, a Texas prisoner named Ray Hall, asking for his version of “T.B. Blues,” together with any old random verses Hall could remember. Hall sent Rodgers what he had, and, as he later recalled, “Jimmie changed words here and there and some of the phrases—that’s the way he worked.” The concluding graveyard phrase, for instance, came from another Rodgers song, “Blue Yodel No. 9.” The result was an altogether new composition, though largely made up of common blues phrases. Porterfield persuasively comments,

“T.B. Blues” is at once intensely authentic and yet calmly impersonal, as if the ominous disease and certain death are someone else’s afflictions. How otherwise could he sing, so eloquently, so stoically, “I’ve been fighting like a lion, looks like I’m going to lose—’cause there ain’t nobody ever whipped the T.B. blues”? . . . From beginning to end, . . . “T.B. Blues” is both an artistic achievement and the most eloquent evidence of Jimmie Rodgers’s tragic vision. It was a vision borne of his own courage and will, of his great zest for life and his own coming to terms with the transience of it, a vision substantial enough to elevate him to the ranks of those poets and painters and artisans whose work illuminates and eases all our human lives.

There is a fine line between self-mythologizing and self-revelation. Somehow, it is easier to believe in a confession if it’s about trouble. And nothing could be more troubling than one’s own imminent death. By singing about it so eloquently, Jimmie Rodgers provided a convincing testament of his dedication to reveal himself to his audience.

RODGERS NEXT RECORDED a number called “Travellin’ Blues,” written by a friend, Shelly Lee Alley, who played fiddle on the record together with his brother Alvin. Finally Rodgers turned to a song whose basic idea had been suggested to him by another one of his San Antonio buddies, Jack Neville: “Jimmie the Kid.” For both numbers he was accompanied not only by Kama, but by local musicians M. T. Salazar on guitar and Mike Cordova on bass.

“Jimmie the Kid” is pure gleeful hokum. It begins, “I’ll tell you the story of Jimmie the Kid—he’s a brakeman you all know,” and then details all the railroad lines he yodeled on. After a while, he tells us that he has a “yodelin’ mama so sweet” and “a beautiful home all of his own—it’s the yodeler’s paradise.” He concludes by both yodeling and singing about it.

“Jimmie the Kid” is the logical outcome of the process that Peer and Rodgers had initiated back in 1927. From the idea of performing only original songs, it’s just a short step to the idea that the songs should wear that originality on their sleeves—and what better way to do that than to sing a song so conspicuously autobiographical that nobody else could possibly sing it?

RODGERS WAS NOT the first to record a song with his name in the title—a number of vaudeville performers did the same. One excellent if obscure example is “Jasper Taylor Blues,” recorded in 1928 by the Original Washboard Band with Jasper Taylor, an African American percussionist from Texas who was based in Chicago. Composed by Taylor along with established songwriters Clarence Williams and Eddie Heywood, the lyrics, sung by Vaudeville singer Julia Davis, celebrate Taylor’s sexual prowess: the chorus runs, “Jasper Taylor, Jasper Taylor—oh, how that boy can love.” Of course, the lyrics are pure braggadocio, yet the song shows that early performers were by no means hesitant to promote themselves in song. Whether any of these songs were truly autobiographical, though, is a question I’ve been unable to answer.

In about 1933, Bonnie Parker wrote a very frank and autobiographical defense of her and her husband’s conduct entitled “The Ballad of Bonnie and Clyde.” We don’t know if she wrote any music to go with the lyrics, but it’s likely she wrote it as a song rather than a poem. The pair were well-known music lovers. Although the song was widely published, nobody recorded it for decades. Of course, it could have been influenced by “Jimmie the Kid,” but more likely both songs drew on a long tradition of outlaw ballads: “Billy the Kid,” “John Hardy,” “Steamboat Bill,” “Sam Bass,” and “Jesse James.” Another question, of course, is whether any of these numbers ended up influencing John Lennon and his “Ballad of John and Yoko.”

AFTER THIS SESSION, Jimmie Rodgers lived another two years and recorded dozens more songs. But none of them were quite as autobiographical as “T.B. Blues” and “Jimmie the Kid.” These were, perhaps even for Rodgers himself, little more than novelty numbers. Something unusual had happened in those two songs, but it was simply too unusual to be repeated very often.

IN 1937, six years after “T.B. Blues,” a then-unknown folksinger named Woody Guthrie wrote a parody of it called “Dust Pneumonia Blues” to the melody of Jimmie Rodgers’s signature “Blue Yodel (T for Texas).” In it, Guthrie sings, “Now there ought to be some yodelin’ in this song, but I can’t yodel for the rattlin’ in my lungs” (perhaps echoing the fact that Jimmie Rodgers had deliberately left his usual yodel out of “T.B. Blues”). Three years later, Guthrie recorded three hours of conversation and songs (including “Dust Pneumonia Blues” and Rodgers’s “Blue Yodel No. 4”) with Alan Lomax for the Library of Congress, discussing only two entertainers at length: Jimmie Rodgers and Guthrie’s fellow Oklahoman Will Rogers. In these conversations, it seems that Jimmie Rodgers was something of a musical father figure for Guthrie. But Guthrie, who may have learned from Rodgers how to project honesty in song, resented the way Rodgers’s fictions could mislead. He talked about how Rodgers’s “California Blues” (“Blue Yodel No. 4”) had painted a false picture of paradise for millions of Southerners who, when they arrived in California, found themselves exploited. Guthrie was taking a very different approach to autobiographical song.

“Dust Pneumonia Blues” became one of Guthrie’s Dust Bowl Ballads, a group of fourteen sides he recorded in 1940 as an album. Many of these songs sound autobiographical: most of them are in the first person and contain intimate details of the narrator’s life—which is more than one could say about most songs of the era. But Woody Guthrie was not, at this time, a celebrity of any kind—the album sold only about two thousand copies—so the listener had no way of telling which of the experiences he sang about he’d lived himself, and which were experiences of people he’d met. And that was his point: these songs were meant to encompass the experiences of a people. Even a truly autobiographical narrative like Guthrie’s later “Talking Sailor,” which humorously relates how he shipped out with the Merchant Marines during World War II, was, in a way, less about Guthrie’s own experiences than about an average American going out to fight the Fascists.

I don’t want to imply that Guthrie refrained from celebrating himself. He was as much of a showman as Rodgers (or, later, Bob Dylan, for that matter) and he was equally concerned about his image. But he made sure that each of his songs had a larger point to make. He wasn’t simply celebrating himself or singing only about his troubles and joys for the pleasure of his fans. Rodgers reveled in celebrity; Guthrie, to some degree, eschewed it. This, of course, in no way makes him less of an autobiographical artist than Rodgers, or less personally authentic. In fact, Guthrie projected his own personality as a bedrock of authenticity that made his artistic and social vision credible and solid. It does help explain, though, why he was far less influenced by commercial considerations.

Guthrie was probably just as central a figure in autobiographical song as Rodgers. He better exemplifies personal authenticity, and he had more of an impact upon the 1960s scene (though that impact would not be strongly felt until after he had become terminally ill and was no longer as creative a force). But Guthrie was quite clearly in Jimmie Rodgers’s debt—one can hear Rodgers’s influence all over Guthrie’s recordings.

MEANWHILE, IN EARLY country music authenticity was still an issue, but it was not until Hank Williams’s appearance in the late 1940s that personal authenticity—the basing of a performer’s appeal on the artist’s integrity and honesty—became its touchstone. Until 1949, country music wasn’t yet called “country”; it had outlasted its previous labels, “old-time” and “hillbilly,” and was now known as “folk.” As Williams, for whom Rodgers was a primary inspiration, defined it in 1952, “Folk music is sincere. There ain’t nothin’ phony about it. When a folksinger sings a sad song, he’s sad. He means it. The tunes are simple and easy to remember, and they’re sincere with them.” Thus Williams eliminated in large measure the “novelty” tone of much of Rodgers’s work; not only did Williams sing his songs as though he meant them, he sang as though his life depended on it.

While Williams’s songs are indeed sincere, they’re not strictly autobiographical, though audiences could catch hints of his real life in many of them. In this sense they were very much like the Jimmie Rodgers songs that Elsie McWilliams had helped him write—Williams’s signature “Ramblin’ Man” was an updated (and far more lonesome) version of Rodgers’s “Rough and Rowdy Ways.” Williams, like Rodgers, had a way of taking his own experiences and making them universal; the autobiographer, however, makes them particular.

So outside of Woody Guthrie and the blues, there just wasn’t much autobiographical song, even by the early 1960s. Was the recording of “Jimmie the Kid” and “T.B. Blues” a fluke, then?

IN SEPTEMBER of 1960, a nineteen-year-old Bob Dylan recorded a handful of songs in his house in Minneapolis. Woody Guthrie’s influence is clear: among them are four of Guthrie’s songs, including the frankly autobiographical “Talking Sailor.” But Dylan also recorded an improvised number about his roommate, “Talkin’ Hugh Brown”; Jimmie Rodgers’s “Muleskinner Blues”; and the Memphis Jug Band’s “K. C. Moan.” And on his very first album, recorded just fourteen months later, Dylan, in an homage to Guthrie, performed a frankly autobiographical song called “Talking New York.” As we’ve seen, Rodgers, Guthrie, and the Memphis Jug Band all had important roles to play in the history of autobiographical song, and Dylan’s tip of the hat to them signifies that something was in the air. It was as if he were tracing the provenance of the mantle that was being passed to him.

Of course, Dylan’s aim in “Talking New York” was not self-revelation but a satirical look at New York City. And Dylan has not recorded many truly autobiographical songs. His liner notes to his second album and “Ballad in Plain D” from his fourth are frankly autobiographical, but after that, he lowered the veil on his personal life. The cult of personality built up around him was based mainly on guesswork and interpretation, for Dylan saw celebrity as a trap. The songs he based on his own experiences were almost always replete with metaphors, disguises, and fictions, and even the publication of his first volume of memoirs in 2004 left most questions intentionally unanswered. But plenty of other folksingers took a more straightforward approach.

By the early 1970s, with the maturity of the “singer-songwriter” genre, everyone was singing autobiography. “The Ballad of John and Yoko” came out in 1969, and Lennon followed it with such autobiographical numbers as “Cold Turkey” and “Mother”; but he had already tentatively ventured into autobiography with “Norwegian Wood” and “Julia.” Folk-rockers were recording autobiographical song back in 1967, the year of Arlo Guthrie’s “Alice’s Restaurant,” Bobbie Gentry’s “Chickasaw County Child,” Paul Revere and the Raiders’ “The Legend of Paul Revere,” and the Mamas and the Papas’ “Creeque Alley.” In 1968, Van Morrison released Astral Weeks, a revelatory record full of autobiography, and one that may remain unmatched in terms of the album as memoir. By the end of 1971, Dolly Parton had cut “Coat of Many Colors,” Loretta Lynn had come out with “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” and James Taylor had had a minor hit with “Fire and Rain,” a song whose press release advertised its autobiographical nature. And these are just a few examples out of hundreds. The floodgates had now opened, and autobiography would remain as conventional a subject for song as love.

WHY DID IT take almost forty years for the autobiographical song to flourish? Why didn’t Hank Williams write a single song that gave us the detail we get from “Meningitis Blues” or “Jimmie the Kid”? Why was Woody Guthrie so alone in telling his own story? Why were blues just about the only autobiographical songs one could find in the 1950s?

In part, it’s because, even at this late period in recording history, both Williams and Guthrie had seen themselves as writing folk songs, songs that anyone could sing, and this was true for Dylan as well. The songs had to strike the right balance between being personal and being universal. The change only began in the 1960s because of the explosion of singer-songwriters, with Dylan and the Beatles leading the pack. It was only then that it became not only acceptable but required for singers to write their own songs.

This imperative was much like Ralph Peer’s four decades earlier, and produced similar results. Personal authenticity now became vitally important. Artists were using autobiography in much the same way as Rodgers had—as a style that emphasized their humanity, realness, and honesty. And the increasingly global nature of celebrity and the music business made it less of a problem if a singer-songwriter’s songs would be hard for another artist to cover.

Just as it became inevitable that blues singers, who sang first-person narratives that purported to be autobiographical, would really begin to sing about themselves on occasion, it soon became inevitable that singer-songwriters would turn their attention not only to generalized love songs, which had long been the domain of songwriters who were not singers, or political messages, which had long been the domain of protest singers such as Pete Seeger, but to their own lives, especially with the strong, positive value put on self-examination in the 1960s.

By now, it’s almost de rigeur to sing about one’s own life, even if one has nothing to say. In 2004 alone, superstars Ashlee Simpson, Usher, and Alicia Keys all had number-one hit albums entitled, respectively, Autobiography, Confessions, and The Diary of Alicia Keys. Artists ranging from Kurt Cobain to Jennifer Lopez to Fifty Cent have used songs as the equivalent of press releases, telling their fans exactly how they want their real lives to be perceived (even when they didn’t write all the songs themselves). Of course, this is exactly what Rodgers and Lennon did too. But while it was once rare, now it’s the name of the game. Is it possible that things have changed so fast? Is it possible that the autobiographical song is really such a recent innovation?

Indeed, it’s more than possible: it’s quite likely. If, in 1925, you were to take a cross-section of Americans, sit them down in a room, and ask them to write a song that tells a story, probably fewer than five percent of them would have written a song about themselves. Instead, they would have written songs about the Titanic, a great flood, a famous outlaw, a local election, or perhaps some woodland animals acting out an old fable. If, in 2007, you were to do the same thing, my guess is that seventy-five percent of them would sing a story about themselves.

Why? Perhaps it can all be traced back to that day in 1931. For the songs Jimmie Rodgers sang then established him as personally authentic, more so than any of the songs he had sung before. Rodgers’s records clearly influenced Woody Guthrie, who in turn influenced Bob Dylan, who in turn influenced Bobbie Gentry, Van Morrison, John Lennon, Tim Hardin, James Taylor, and a host of others. Following a different track, Rodgers’s records clearly influenced Hank Williams, Tom T. Hall, Loretta Lynn, Dolly Parton, Merle Haggard, and a host of others. The line may not be unbroken or even all that clear. But it never is, is it?

Although the story of autobiographical song may seem disjointed, peculiar, and unnatural, one point is inescapable. Autobiographical song is relatively new and postdates almost every other element of popular song lyrics as we know them.

What does this tell us about the quest for personal authenticity, then? Simply that revealing oneself in song, a goal that we now all take for granted, is a rather recent and comparatively artificial development in the history of popular music. We now think of autobiographical song as a natural form of expression, but as anyone who has ever tried can attest, writing a song based on one’s own life, with a verse and chorus structure, that will appeal to a mass-market audience is no simple matter. It is far easier to sing about almost anything else.

IN RETROSPECT, we can isolate seven functions of or impulses behind autobiographical song, and by doing so we can make it easier to understand the differences between “Meningitis Blues,” “T.B. Blues,” “Jimmie the Kid,” “Talking Sailor,” “Pennyroyal Tea,” and “Jennie from the Block.” Some autobiographical songs may partake of only one of these, others of all seven.

First, there’s the primal need for confession, an essentially private impulse that is basic to all of us.

Second, there’s what we can call the blues impulse. The blues is, as we’ve seen, a first-person song about quotidian yet troubling experiences with which the audience can sympathize. It was also the basis for Jimmie Rodgers’s appeal. The reason some people sing the blues is in many cases exactly the same reason they’ll introduce autobiographical elements into their song.

Third, there are market forces that pressure singers to be original, and being autobiographical is a logical outcome of that pressure. This is exemplified both by Ralph Peer’s pressure and the situation created by the popularity of Dylan and the Beatles in the 1960s.

Fourth, there’s the Will Rogers phenomenon, realness—the desire to be genuine, to present not a persona but who you really are to your public. Related to this is the desire to make an intimate kind of music.

Fifth, there’s what I call the press release function. “T.B. Blues” was Jimmie Rodgers’s way of telling his fans that he was dying. Before he recorded this song, they would have had to rely only on rumor. This function, like the last, is intrinsically tied to and dependent on notions of celebrity.

Sixth, there’s plain old boastfulness. This applies to songs like “Jimmie the Kid,” the vaudeville numbers that preceded it, and a large number of hip-hop songs.

Seventh, there’s social comment. This was not a function of Jimmie Rodgers’s autobiographical songs, but was a major feature of those by his primary successor, Woody Guthrie.

IT IS NOT HARD to assume that the more autobiographical singers are, the more honest or authentic they are. Certainly Memphis Minnie’s “Meningitis Blues” was more confessional than Victoria Spivey’s “T–B Blues,” and Jimmie Rodgers’s “T.B. Blues” was more personal and heartfelt than most of his blue yodels. Yet there’s also something highly artificial about certain autobiographical songs, ranging from “Jimmie the Kid” to “The Ballad of John and Yoko” to “Jenny from the Block.” Are artists who go to great lengths to construct a song around those aspects of their lives that are already public knowledge being more honest than those who sing about fictional or universal subjects? Or are they self-consciously attempting to control their public personas through song?

There is no one-to-one correspondence between being true to yourself and singing about yourself. Using elements of autobiography in song to show how real one is, as most of the artists discussed in this chapter did and so many more do these days, can sometimes be less honest than simply singing about whatever comes most naturally.

And, as the example of Lightnin’ Hopkins shows us, even that can get a bit boring after a while. We need some theatricality in the music we listen to. Autobiographical song, as in the case of “T.B. Blues,” can sometimes provide us with that. And perhaps that—pure, simple entertainment—is its eighth and most important function.